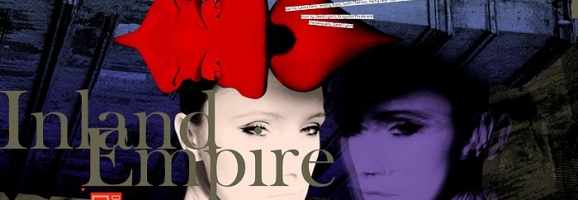

David Lynch and Maya Deren: the Psyche through Cinema

At screenings of Inland Empire, David Lynch has been known to limit his introduction to a cryptic epigraph: “We are like the spider. We weave our life and then move along in it. We are like the dreamer who dreams and then lives in the dream. This is true for the entire universe.” Given how his film ensnares both characters and spectators in a vast terrain of fantasies, forcing both to perceive from within its sprawling web, he could not have chosen a more dexterous foreword. Inland Empire is no less than a “meta-menace”: two films within a film, both of which are cursed.

Nikki Grace aspires to star as Susan Blue in the present day film On High in Blue Tomorrows, in what she envisions as her comeback role, only to discover that it is in fact a remake of a movie called 47, whose two leads were brutally murdered after becoming romantically entangled offset. She receives a visit from an enigmatic Polish woman who evokes the film’s sinister origins and holds her in a trance as we jump ahead to when Nikki gets the part. As Nikki becomes steeped in her role, however, the callous persona of Susan Blue takes over, so overwhelmingly that we begin to wonder whether Nikki isn’t concealing a similarly sordid past, or if it isn’t just through sheer fantasy that she has incorporated herself into this “cursed” film in an attempt to romanticize her actual life on the margins of Hollywood. After all, there is no way to authenticate the 47 “footage,” which could either be real memories of her unhappy past or else her fevered projections as a failing actress. The wife of the original film’s star – known as the Lost Girl- may be yet another one of her buried personas or identities.

Yet, in a potential radical reversal, which Lynch executes as the Lost Girl watches Nikki on screen, the film On High in Blue Tomorrows could be the object of her fantasies, a cathartic reversal of her unspeakable past, where jealousy- “the Phantom”- drove her to murder her husband. Because of these reciprocal realities on either side of the screen, one character’s story can never be reduced to the mere material of another’s fantasies. While Susan Blue might be the fictional star of On High in Blue Tomorrows, neither she nor Nikki Grace nor the Lost Girl is the centermost character of Inland Empire. Through Lynch’s digital dexterity, the framed narrative has been dissolved.

Instead, the dreamlike lattice of his film distinctly borrows from one of the earliest experimental filmmakers, Maya Deren, and her equally enigmatic but more compact masterpiece Meshes of the Afternoon. Deren also deconstructs a woman in trouble, who finds herself imprisoned by a reality that eerily corresponds to the contours of her nightmare. As if to literally foreshadow that this will be a film about the obscure territory of her subconscious and her projected fantasies, the first image we see is of her own silhouette, advancing up the drive, as she retains only the briefest glance of another indistinguishable figure- Death- disappearing around the bend. That is, the film has the incorporeal feel of a dream before we are telescoped through her eye and suctioned into a self-replicating nightmare, where a metonymy of mundane objects mutely unveils her suicidal drives.

As in Lynch’s film, the woman is fragmented into multiple personas. The first- like the obsessed and apprehensive Nikki- chases after the hooded figure down the drive, while a second watches from the window, with the hardened cruelty of Sue, as she pulls a key from her mouth, which later mutates into a kitchen knife as she holds it out in her palm and offers it to her “other selves.” Deren has also inverted the framed narrative by abstracting us further and further from the film’s supposed core, weaving reality outward so that the woman’s sleeping body is caught like a mere fly at its center.

Just as Nikki never fully emerges from her trance as Susan Blue, there is never a moment in Meshes when the woman finally “wakes up.” There is merely a mounting sense that her life and her nightmare are one and the same, culminating in her final act of suicide, where her husband finds her surrounded by the same shards of glass that belong to the face of the hooded phantom figure. While we can conclude that death symbolizes the only escape from her ever-nascent nightmare, the end is ambiguous, leaving us to wonder whether her death was real or imagined. Deren’s film, like Lynch’s, is premised on a premonition, confounding our attempts to determine if key moments are actually unfolding at a future point in time or if we are merely caught inside the apprehensions of a character’s mind.

Deren’s legacy is palpable in Lynch’s will to externalize the psyche through cinema. An outspoken anti-realist, Deren affirmed that if cinema “was to take place beside the others as a full-fledged art form, it must cease merely to record realities that owe nothing of their actual existence to the film instrument.” For an art form as advanced as cinema, to replicate reality was hardly an artistic feat. Its full potential would be unleashed not as an approximation of “Reality,” but as an approximation of consciousness, where the film medium would be used to draw attention to synaptic leaps in time and space that sustain and interweave multiple realms of thought.

It is no accident, as John Kenneth Muir notes, that Lynch’s Axxon N- the “longest radio play in history”- evokes the word “axon,” the part of the cell that conveys impulses, linking remote realities in the same way Nikki’s passage through the door marked Axxon N brings her into the worlds of the Lost Girl and the Rabbits sitcom. Lynch fans also elicit the possibility that the apparently absurd name was crafted through the fairytale permutations of Vladmir Propp’s Morphology of Folktales– an analysis of myths and folklore as being exponentially interconnected, across time and place, through a regenerative set of 31 “narratemes”- or narrative units. As a remake of the film 47, On High in Blue Tomorrows can be schematized as a rebirth of this myth through a reconfiguration- if not an inversion- of its elements: a married man, a prostitute, an infertile spouse, a deadly Phantom figure, a doomed love affair, and a jealousy-driven murder. These twin myths are, in turn, conjoined by the Polish woman’s folktale from the beginning- Sue, half born, loses her way in the marketplace during one of her scenes and passes into “the palace,” where her spiritual counterpart or unborn half, the Lost Girl, imagines her reunion with her dead husband and miscarried son.

Indeed, the close-up on Zabriskie’s face at the very end has the effect of engulfing the last two hours in a high cheek-boned trance, causing them to slip into a mythic realm where precise time and place are forgotten- an unstable impression enhanced by Lynch’s signature use of a low-grade digital camera, where images seem to materialize and decay in a single breath through the grainy gossamer of the screen. Despite its length, the film is one vast fleeting instant- of adultery and death- whose imminence is reincarnated across time and place. It is no surprise that when Lynch began shooting, he had the scattered seeds of something far more exponential than a well formulated plot: a vague 14-page monologue of a victimized woman, containing only minimal context beyond the troubled meshes of her mind, but from which the film would ultimately weave itself outward into its empire of intersecting aesthetics.

What Lynch achieves, with ambitious scope, is Deren’s vision of film as an “anagram”- a set of elements that cannot, and should not, be read linearly, and whose artistic integrity resides in the whole, regardless of how these elements are arranged. Rather than simply explain the characters’ fates as the product of a “cursed” script, we are made to consider their possible fates through a simulated simultaneity of events that makes up the consciousness of the movie itself. The more porous Inland Empire becomes, the more it crystallizes to form this structure that Deren saw as maximizing what will always be the most mystical and manipulable elements of filmmaking- time and space: “Nothing is first and nothing is last. Nothing is future and nothing is past; nothing is old and nothing is new . . . except, perhaps, the anagram itself.”

Works Cited

Guillen, Michael. “INLAND EMPIRE- The San Rafael Film Center Q&A With David Lynch,” Twitch, posted January 24, 2007, accessed June, 15, 2014, <http://twitchfilm.com/2007/01/inland-empirethe-san-rafael-film-center-qa-with-david-lynch.html>

Deren, Maya, “Cinematography: The Creative Use of Reality,” The Avant-Garde Film: A Reader of Theory and Criticsm (New York: Anthology Film Archives, 1978), p. 72.

Deren, Maya. “Preface.” An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film, The Alicat Book Shop Press (Yonkers, New York: 1946), p. 5.

Dundes, Alan. “Chapter II: The Method and Material,” Excerpts from: Vladímir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, 1928, Translation 1968, The American Folklore Society and Indiana University.

Muir, John Kenneth, “CULT MOVIE REVIEW: Inland Empire (2006),” posted June 11, 2010, accessed June 27, 2014, <http://reflectionsonfilmandtelevision.blogspot.com/2010/06/cult-movie-review-inland-empire-2006.html>

Nieland, Justus. “Vital Media: Inland Empire,” David Lynch (Contemporary Film Directors), University of Illinois Press (Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: 2012), p. 138.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I find Lynch a truly remarkable and one of the greatest directors ever. His movies receive very mixed reviews mainly because they are so personal I believe. Some people say you have to let his movies wash over you, others want to dig in and search for meaning and yet others will find his movies boring and pretentious.

I thought it was an interesting film but I would likely not watch it again (it’s kind of exhausting to watch). But I liked how original it was.

This film is atrociously, unspeakably, unbearably awful. It makes NO sense. None. Anyone who tells you it does? They are just too pretentious to admit this is a nonsensical pile of mess.

You mad?

Good piece. This movie is for those with some patience, able to absorb the feeling being conveyed and appreciate it for the experience that it is.

I think the best word to describe someone like David Lynch is just weird.

This was the greatest stab at surrealist film since the Cremaster Cycle. For Lynch, just after filming Mulholland Drive, to go all out and make three hours worth of non-interconnected, abstract, surrealist, subjective vignettes is bold. What, oh what a film.

If all he really wanted to do was blur the distinction between fantasy and reality, and in the process make his viewers become just a little unhinged… well, I think he succeeded in spades.

Your writing style is highly engaging and clear! Interesting read 🙂

I honestly felt that Lynch made this film while having some sort of psychotic episode. I was baffled, which is not a bad thing, but also very irritated by the film, and that IS a bad thing. What there was of plot was incoherent and confusing. I do admit that there were some interesting visual images, which one would expect from Lynch.

Watching this was like sitting through a chaotic nightmare that will never end.

Check out this Amazon eBook that explains David Lynch’s INLAND EMPIRE. David Lynch’s INLAND EMPIRE Explained by Mike Lidstone. Here is the link:

http://www.amazon.com/David-Lynchs-INLAND-EMPIRE-Explained-ebook/dp/B004LGS7I6/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1446043918&sr=8-1&keywords=lynch+inland+empire