Dragons: East versus West

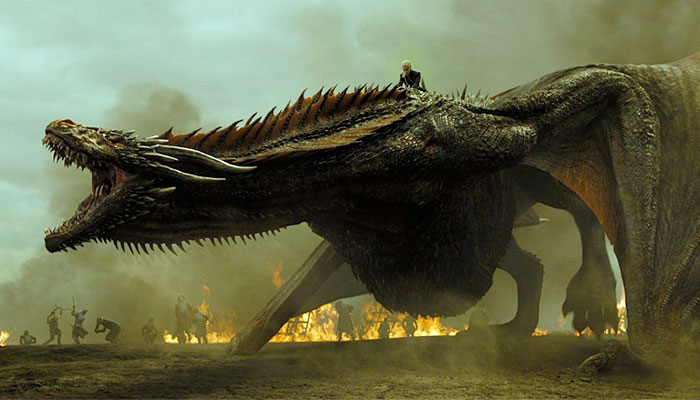

The dragon is one of the most recognizable figures in literature. It has appeared in Greek myths, Norse sagas, medieval legends, video games, TV programs, and especially movies. It has transcended time and geography to become a cultural icon.

However, the dragon is much more complex than presented in the media. Most people are familiar with the two-winged, four-legged beast, a force to be reckoned with. But the truth is that there are many different versions of the dragon from different cultures. This article will examine some of them, comparing those from the West (Europe) with those from the East (Asia). Legends from the Americas and other regions will also be highlighted.

Dragons in the West

The Mediterranean (Mesopotamia, Greece, and Judea)

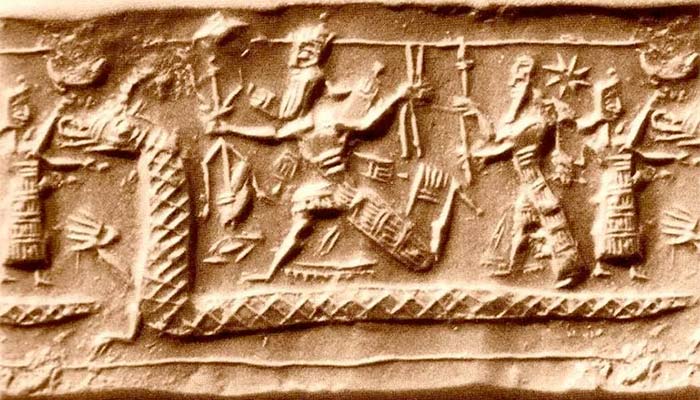

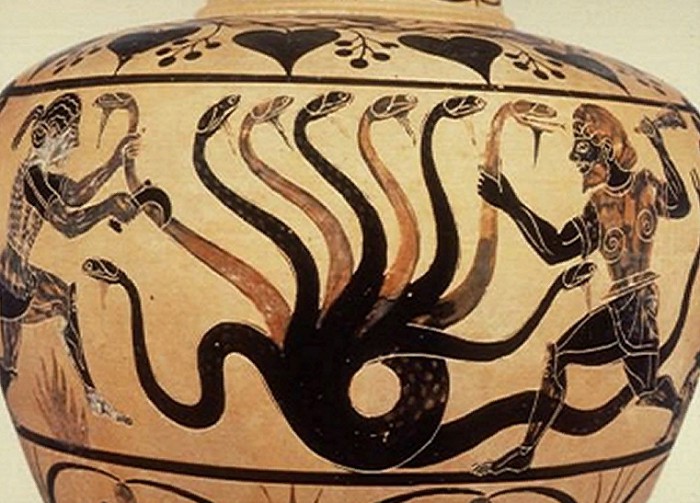

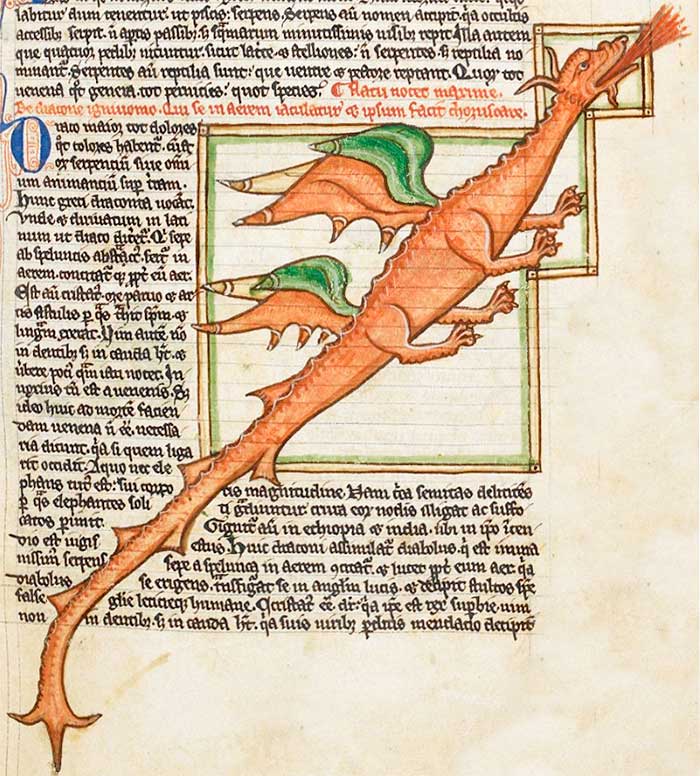

The earliest representations of the dragon were as large snakes. This is because the word “dragon” comes from the Greek drakōn, which means “serpent” or “giant seafish.” The practice of depicting dragons as snakes is present in many Mediterranean communities.

One of the oldest stories about dragons comes from Mesopotamia, specifically the creation story Enuma Elish. In it, the Mother Goddess (and the personification of the sea) is Tiamat, who is said to have taken on the form of a dragon. She wages war against her children and the Babylonian king Marduk, who ultimately kills her and creates the world from parts of her corpse. This isn’t the last story where dragons play a role in creation, and certainly not the last dragon slayer story.

Heroes-vs.-dragons myths also pop up in Greek literature. The most famous is Heracles’ (Roman: Hercules’) Second Labour, which is to slay the Lernaean Hydra. The Hydra is a monster with nine (or more) heads, which can regenerate except for one immortal head. Its blood also has poisonous properties, something that is present in later dragon legends.

Dragons make some notable appearances in the Old and New Testament. The actual term is used for all large, sea-dwelling monsters as well as snakes. The Hebrew Torah in fact calls Emperor Nebuchadnezzar and the Egyptian Pharaoh the word “tannin”, or sea monster. The King James Bible translated from the Hebrew and Greek use the word dragon in the same way (mainly because the word “dinosaur” hadn’t been invented yet). For example, here is a passage about the sea creature Leviathan:

“In that day the LORD with his sore and great and strong sword shall punish leviathan the piercing serpent, even leviathan that crooked serpent; and he shall slay the dragon that [is] in the sea”

King James Version, Isa. 27:1

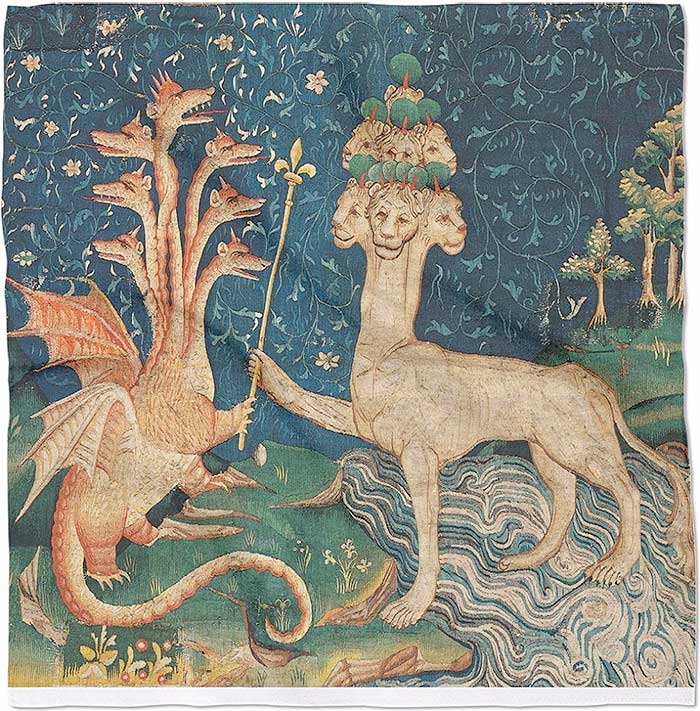

Actual dragons appear with the literal ones. The prophet Daniel kills a dragon kept for worship in Babylon in a lesser known version of the “lions’ den” story. However, the most well-known example of a Biblical dragon comes from the Book of Revelations, where it is used as a symbol for the Devil himself:

“And there appeared another wonder in heaven; and behold a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads.”

King James Version, Rev 12: 3-4

In Revelations, Satan appears as a dragon and tries to harm the Virgin Mary and her newborn Son. He later wages war against the Heavenly forces. Of course, he is defeated and thrown to Hell with his minions.

Already, there is a common thread in these different stories: the dragon as a symbol of evil, an obstacle to the hero. This theme will continue into, and peak in, Europe in the Middle Ages.

Medieval England and Wales

It was in the mid to late Middle Ages that the typical image of a dragon, and popular features such as its fire-breath and underground lairs, were solidified. The snake was now a lizard with bat wings and four legs (to distinguish it from the two-legged “wyvern”). Like in Roman times, the dragon decorated standards of the royal family, most famously Uther Pendragon’s.

The story of Saint George and the Dragon became a classic example of a tale of chivalry and the triumph of good (Christianity) over evil (Satan and sin). Although there was an actual martyr named George, it’s doubtful whether he actually killed a dragon. Other Christian stories involving dragons include Saint Margaret of Antioch (whose prayers repel a dragon) and the priest Romanus (who creates the first gargoyle using a severed dragon’s head).

As far as fictional dragon stories go, the epic Beowulf stands out as one of the best. At the end of the poem, the titular hero, now a king and elderly, goes to fight against a dragon that is terrorizing his people. The unnamed dragon is one of many literary dragons to have his own treasure hoard, and is very protective of his possessions. So when a slave steals a gold cup, he is naturally very upset:

“…[T]hen the ward of the barrow/

Beowulf 32. 82b-84

Was angry in spirit, the loathed one wished to/

Pay for the dear-valued drink-cup with fire.”

Beowulf and the dragon fight and, while the creature is defeated, the king is mortally wounded. Unlike most dragon-slayer stories, this one doesn’t have a happy ending.

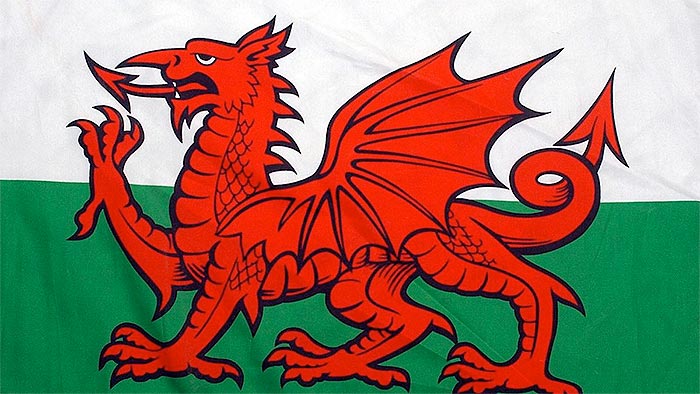

A study of medieval dragons wouldn’t be complete without the story of the warlord Vortigern and the wizard Merlin. According to a legend found in the History Regum Britanniae, Vortigern wanted to build a tower on Mount Snowdon. Unfortunately for him, the foundation kept sinking. On draining the pool, Vortigern found a red dragon and a white dragon, which immediately started fighting each other. Merlin predicted that the white dragon would defeat the red, but that the red dragon would return and ultimately be victorious. This story is the reason why dragons are shown on badges, coats of arms, and flags even today.

Scandinavia

The image of a greedy dragon with a treasure trove also appears in Norse mythology. J.R.R. Tolkien’s Smaug, from The Hobbit, was probably inspired by the dragon Fafnir. According to the Völsunga saga, Fafnir was originally a dwarf prince who killed his father for a reward from the god Odin. The gold is cursed, however, and Fafnir turns into a dragon. He is later killed by the hero Sigurd, who gets both the treasure and the ability to understand birds (don’t ask).

But Norse dragons could cause more damage than just a blast of hellfire. They could wreak major environmental and elemental damage. For example, there is a large dragon or serpent named Níðhǫggr that is slowly gnawing away at the roots of Yggdrasil, or the Tree of Life. Another, more massive, creature named Jörmungandr (also called the Midgard Serpent) lives in the sea, encircling the earth and gnawing on his tail, waiting to fight the god Thor during Ragnarök (the Apocalypse).

Just like in Judeo-Christian tradition, Vikings saw the dragon as a force of evil and destruction. However, similar to the Romans, they also saw him as a symbol of wealth, prosperity, and power. That’s why there are so many depictions of dragons on longships, shields, and flags, whether as snakes, dragons, with wings, or without.

Dragons in the East

China

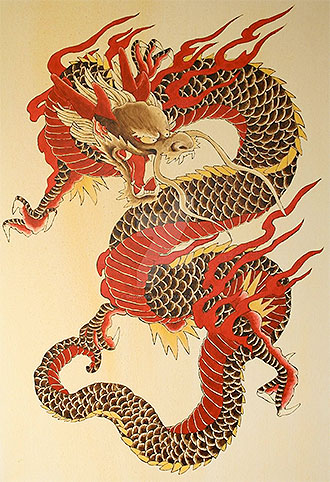

The Chinese dragon is probably the most iconic creature in Chinese culture. It’s certainly one of the strangest. Unlike the Western dragon, its physical features are a little more involved. According to Chinese scholar Wang Fu:

“The people paint the dragon’s shape with a horse’s head and a snake’s tail. Further, there are expressions as ‘three joints’ and ‘nine resemblances’ (of the dragon), to wit: from head to shoulder, from shoulder to breast, from breast to tail. These are the joints; as to the nine resemblances, they are the following: his antlers resemble those of a stag, his head that of a camel, his eyes those of a demon, his neck that of a snake, his belly that of a clam (shen, 蜃), his scales those of a carp, his claws those of an eagle, his soles those of a tiger, his ears those of a cow. Upon his head he has a thing like a broad eminence (a big lump), called [chimu] (尺木). If a dragon has no [chimu], he cannot ascend to the sky.”

There are other features that identify a Chinese dragon. He has whiskers and a beard, shorter than a Korean dragons, and four or five claws. He is also depicted with a flaming pearl (representing the moon, wisdom, or immortality) under his chin or in his claws. A Chinese dragon isn’t usually shown with wings, but he is able to fly.

Unlike the Western dragon, the Chinese dragon is a symbol of good (the yang, or light side), prosperity, good fortune, power, and the elemental forces (including rain). Many Chinese claimed to be descendants of dragons, including the Han Chinese and the Emperors. In later dynasties, only the Emperor could decorate his home and possessions with symbols of the dragon, and only his family could wear the official colors of the dragon (yellow for the Emperor and Empress, apricot for the crown prince, and golden yellow for the Emperor’s other wives). The Qing dynasty (1862-1912) even featured a dragon on the imperial standards.

As might be expected, there are many legends surrounding the Chinese dragon. There are several stories connected to the Snake Goddess Nü Gua, who sometimes depicted as a dragon. She is said to have created the first humans and invented music. However, Nü Gua’s most famous exploits see her saving the world from terrible fires, catastrophic floods, and – oddly enough – a Black Dragon.

The Black Dragon is actually one of four Dragon Kings supposed to be guarding the four seas (East China Sea, South China Sea, Qinghai Lake, and Lake Baikal). The Kings also control water-related weather and phenomena. Finally, there are the Nine Dragon Children, which are present in many areas of Chinese art, architecture, and culture.

It would be impossible to list all the ways Chinese dragons appear in everyday life, so here are some examples: At Chinese New Year, a special dragon costume “worn” by several people dances in parades and special ceremonies. Dragon Boat Festivals are held in China, Vietnam, Korea, and any place with a large Asian community. Finally, many couples try for children in the Year of the Dragon, when it is said leaders and influencers are born.

Japan

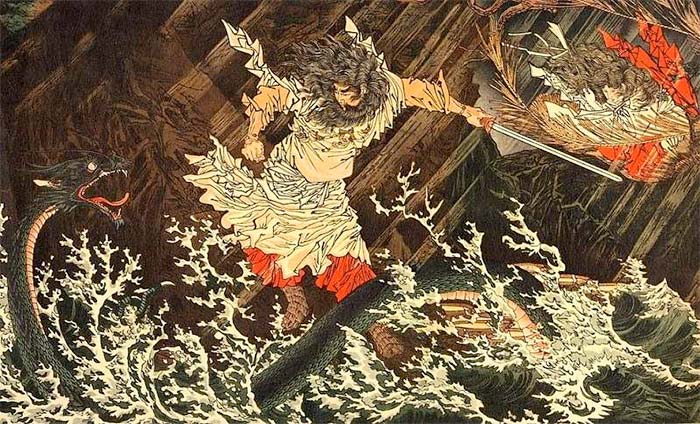

Buddhism came to Japan through monks from India. This is why Japanese dragons have both Chinese and Indian influences. Japanese dragons look similar to their Chinese counterparts; however, they only have three claws.

Another key difference is that Japanese dragons are much more malevolent and destructive. The best example is the eight-tailed, eight-headed monster named Yamata no Orochi (or just Orochi). Orochi lived in the Hi (Hit) River and devoured the daughters of the kunitsukami (earth gods). His reign of terror ends when the god Susano’o kills him.

The Dragon King Ryujin is one of the more benevolent dragon figures. Also called Owatatsumi no Kami, or Watatsumi, he lives under the sea with his many daughters. His granddaughter (in some legends his daughter) Toyotama-Hime is believed is said to have been the ancestress of Japan’s first Emperor, Jimmu.

Today, there are many Buddhist temples and shrines in Japan named after dragons, connected to dragon legends, and/or decorated with dragon imagery. There are also special events celebrating them at these sites. One of the most popular is the Kinryu no Man (Golden Dragon Dance) held at the Kinryuzan Sensoji Temple in Asakusa. Another is the Dragon Festival and fireworks held at the Lake Saiko Dragon Shrine in Fujiyoshida, Yamanashi.

Vietnam

The Chinese weren’t the only people claiming to be descendants from dragons. According to legend, the Vietnamese come from a union between a dragon and a fairy, giving them the name “con Rong chau Tien”.

Here is the story: A magician named Kinh Duong Vuong marries the Dragon Princess Long Vu. Their son, Lac Long Quan, travels throughout Linh Nam (ancient Vietnam), slaying monsters before marrying the fairy Au Co. The couple has hundred children and later split up, each partner taking fifty children. Lac Long Quan settles on the coast and valley, while Au Co goes to the mountains. The oldest son becomes king and starts the Hong Bang Dynasty, Vietnam’s first dynasty.

Another popular legend about Vietnamese dragons is connected to Ha Long Bay, which translates literally to “Bay of Descending Dragons”. In it, the Viet people are under attack from foreign invaders. The Mother Dragon and her Children help the Viet by building jade islands that destroy the enemy ships. The Dragons remained at the site after the armies fled, and Ha Long is said to be the place where the Mother Dragon landed.

Like the Chinese dragons, Vietnamese dragons are symbols of the yang, life, growth, and prosperity, said to bring good fortune and rain. Its depictions evolved throughout the different dynasties, but the modern dragon has a spiral tail, sword-fin, and a large head. As in Japan, many Vietnamese places are named after dragons.

India

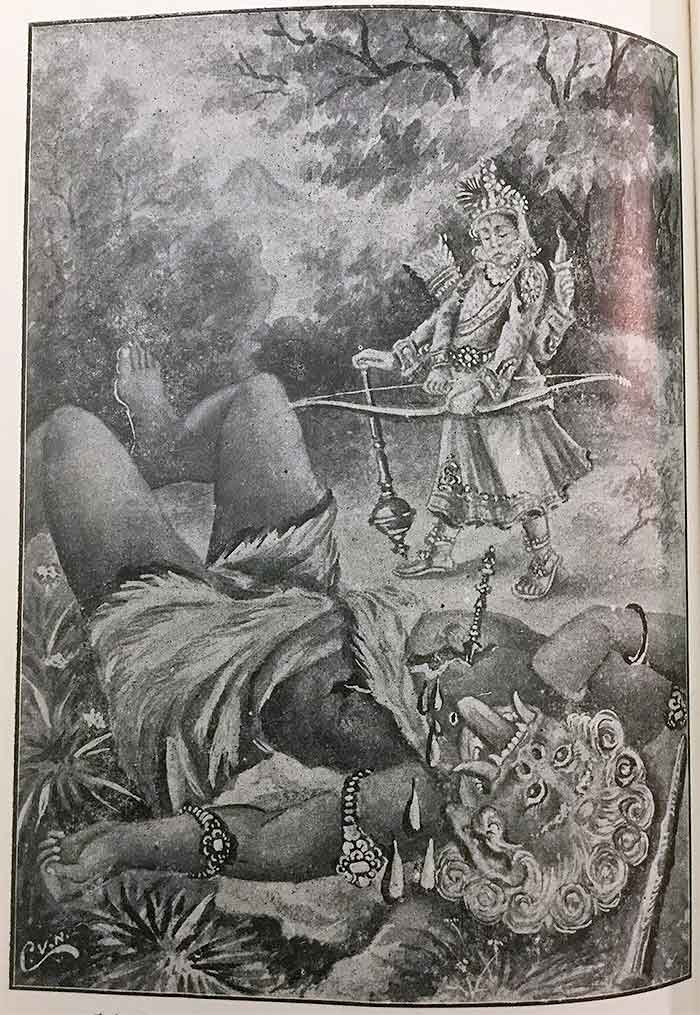

Dragons also appear to a certain extent in East Indian mythology. For example, there is the serpent Vritra (or Ahi), who brings drought to the world by blocking of all the water. In most versions of the story, he is killed by the god Indra, but in one variation it is the goddess Sarasvati that kills him.

Another dragon or serpent-like creature is the nāga. Also appearing in Japanese folklore, the nāga is a nature spirit typically shown as a cobra. It lives underwater and is in charge of rivers, lakes, wells, and other places in or near water.

Finally, there are many dragons in the mythology of the Meitei people in Manipur (northeast India). The supreme god Pakhangba is a dragon who protects the Earth and destroys evil. The creator of the universe is the dragon Nongshaba (Kanglasha), who also takes on the form of the lion. And there are many water-based dragons, including the Poubi Lai and Loktak Maru Sidaba in Loktak Lake.

Dragons in Other Parts of the World

Although this article focus on dragons in the East and West, it’s worth checking out creatures from other countries’ folklore.

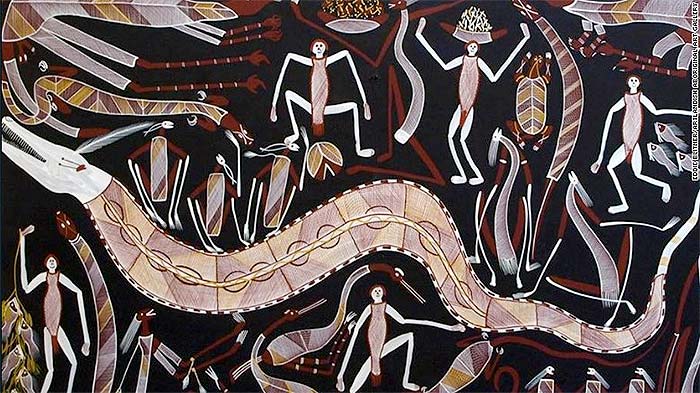

The Rainbow Serpent plays a major role in the creation story of the Aboriginal people in Australia. In the most popular version, the Serpent sleeps under the Earth, which at the time is a barren wasteland. After it wakes up, the Serpent creates the sun and fire, forms mountains and lakes, and wakes up the animals. The Rainbow Serpent appears as male, female, or androgynous depending on the version of the story and can be seen in art dating back to 6000-8000 years after the last Ice Age.

In North America, the Native Americans have stories of the Horned, or Great, Serpent. The Serpent has many different names depending on the tribe and region, but it is usually associated with water, rain, thunder, and lightning. Special powers include shapeshifting, hypnosis, healing abilities, and control over weather. Some variations on the Horned Serpent, including the Unhcegila (Sioux tradition) and Djodi’kwado’ (Iroquois), portray him as evil and destructive, while others (such as the Muscogee people’s Horned Serpent) see him as harmless.

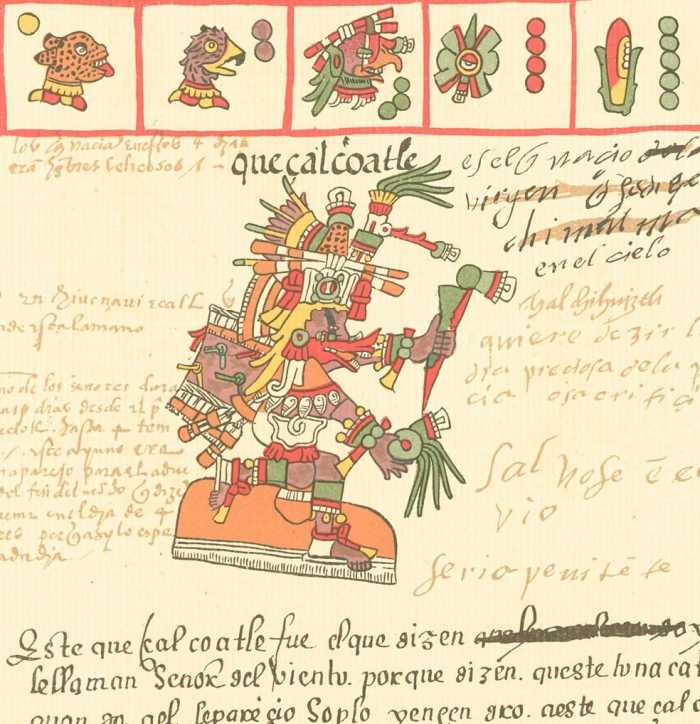

The Aztec people, who once lived in central Mexico, worshipped the Feathered Serpent Quetzalcoatl. First worshipped as a vegetation god, he was soon revered as a wind god, the patron of priests, the one who invented books and calendars, and even sometimes as the symbol of death and resurrection. Usually portrayed as a snake head, Quetzalcoatl was also depicted as a man with a conical hat, red duck-billed mask, and shell jewelry after 1200 AD.

Gods and demons. Creation and destruction. Fire and water. Life and death. These are just some of the interpretations given to the dragon. There is no wrong answer. All stories come from the cultures and traditions of different peoples, each with its own perspective and emphasis.

What is wrong is to assign only one meaning to the dragon, or to see him in only one light. Whether as a symbol of good or evil, the dragon is a source of inspiration and wonder, and he will continue as such for centuries to come.

Works Cited

Admin. “Viking Symbols and their Meaning.” Viking Style, 17 Jan. 2020, https://viking.style/viking-symbols-and-their-meaning/. Last accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

Beowulf. Translated by Lesslie Hall, D.C. Heath & Co., Publishers, 2005.

BibleStudyTools Staff. “Dragons in the Bible.” Bible Study Tools, 23 Jul. 2018, https://www.biblestudytools.com/topical-verses/dragons-in-the-bible/. Last accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

Burch, James. “Dragons Don’t Exist. So Why Are They Everywhere?” All That’s Interesting, 6 Sept. 2019, https://allthatsinteresting.com/dragon-legends. Last accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

Cheyanne. “10 Amazing Facts on Chinese Dragons.” ChinaHighlights.com, 24 Nov. 2019, https://www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/chinese-dragon-facts.htm. Last accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

Ḏḥwty. “Tiamat, Mesopotamian Mother Goddess: From Chaos to Creation.” Ancient Origins: Reconstructing the Story of Humanity’s Past, 28 May 2019, https://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends-asia/tiamat-mesopotamia-0010565. Last accessed 14 Sept. 2020.

Eidt, Jack. “Aboriginal Dreamtime: The Rainbow Serpent.” WilderUtopia.com, 12 Apr. 2012, https://www.wilderutopia.com/traditions/myth/aboriginal-dreamtime-the-rainbow-serpent/. Last accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

Rouă, Victor. “Ancient Dragons In The Norse Mythology and Scandinavian Folklore.” The Dockyards, 10 Jan. 2017, http://www.thedockyards.com/ancient-dragons-scandinavian-folklore-mythology/. Last accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

Visser, Marinus Willem de. The Dragon in China and Japan. J. Müller, 1913.

The Bible. Authorized King James Version, Oxford UP, 1998.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Fafnir.” Britannica.com, 4 Jun. 2009, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Fafnir. Last accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Quetzalcóatl.” Britannica.com, 7 Apr. 2005, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Quetzalcoatl. Last accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

“The Myth of Nü Gua Chinese Snake Goddess.” Acutonics®, 19 Jan. 2013, https://acutonics.com/news/the-myth-of-nue-gua-chinese-snake-goddess/. Last accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

“The Vietnamese Dragon: Legend, History & Geography.” Viet Vision Travel, https://www.vietvisiontravel.com/post/the-vietnamese-dragon-myth-history-and-geography/. Last accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

“Vietnamese Dragons History, Mythology and Physiology.” Draconian.com, http://draconian.com/dragons/vietnamese-dragon.php. Last accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

Wikipedia contributors. “Chinese dragon.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 7 Sept. 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_dragon. Last accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

Wikipedia contributors. “Dragons in Meitei mythology.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 13 Sept. 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dragons_in_Meitei_mythology. Last accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

Wikipedia contributors. “European dragon.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 9 Sept. 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_dragon. Last accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

Wikipedia contributors. “Horned Serpent.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 8 Aug. 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horned_Serpent. 15 Sept. 2020.

Wikipedia contributors. “List of dragons in mythology and folklore.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 16 Aug. 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_dragons_in_mythology_and_folklore. Last accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

YABAI Writers. “The Japanese Dragon – Myths, Legends, and Symbolisms.” YABAI, 7 Nov. 2017, http://yabai.com/p/2516. Last accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Chinese dragon is more like a snake but with 4 legs… it really doesn’t look much like European dragons. If you hadn’t heard the term “Chinese DRAGON” for it for many years, you probably wouldn’t look at say “that’s a dragon!” based on European depictions.

Asian dragons & European dragons are very different creatures once you look past the “giant lizard” bit.

The Chinese dragon has a long snakelike body and parts from other animals while the European dragon is just a big lizard. More importantly, European dragons are almost always evil while Chinese dragons are good.

If you remove the shared name, it’s highly unlikely you’d consider them to be the same beast.

Also, European dragons can normally fly.

So could Chinese Dragons. They just sort of undulated through the air in most depictions.

Most of the european dragons are more snake like than lizard like.

What’s your favorite Dragon statues?

Not exactly realistic up Close, but the Tower of London has a big dragon statue made up of medieval weapons.

Check out pictures of Ljubljana Slovenia. Start with the Dragon Bridge. Idk that it would be considered ” big” but it’s amazing

Brickley the LEGO water dragon in Orlando, Florida, is fairly realistic if slightly cartoonish.

In Klagenfurt in Austria there is a fountain with a ‚Lindwurm‘ from 1593. The lindworm is also the heraldic animal of the city.

Caerphilly Castle (wales)has some big dragon statues that are pretty cool.

I had a discussion with a Chinese friend regarding the merits of European vs. Chinese Dragons. He said Chinese dragons were better because they could fly without wings. I pointed out that European dragons were always depicted with wings because Chinese dragons aren’t real.

I remember reading this theory that dragons represented a composite of all of early man’s predators. These being snakes, birds of prey, and large cats.

Birds of prey?

And snakes aren’t our predators – they’re a lot more dangerous if you startle them than, say, a kestrel, but that doesn’t mean we’re part of their diet.

One of my favourite dragons is Terry Gilliam’s Jabberwocky. Beautifully realised. I love the bit at the start where Terry Jones gets carried off screaming and then bloody, flesh-covered bones fall from the sky. (The rest of the film is a bit shit).

If I recall correctly that was the first film in which I saw an unadorned pair of breast (that weren’t a source of milk)

I seem to remember a very plausible BBC children’s programme which looked at the scientific evidence for dragons existing. I can’t remember much except for the calcium from human bones ( the sacrificed maiden ) being used to create – hydrogen (?) and the dragon’s fiery breath was a buoyancy device for getting rid of excess gas. The wing design was fed by this as it only needed to glide etc.

Anyone else remember it better than I can?

I remember that – though I thought it was C4, a well thought out programme

Some years back I attended an exhibition on Dragons throughout History and in various parts of the world in the beautiful setting of the Castle of Gaasbeek near Brussels.

The very first item was a dinosaur fossil with eggs. The inference was clear that dinosaur remains could have given rise to the myth of the dragon.

I always thought the reason dragons were reptiles was because they originally came about as a more exaggerated representation of a serpent which, in turn, was used to represent the devil in Christian tales.

I love dragons and, if anyone who wants to know more about them, there is a great book titled ‘The Flight of Dragons’ by Peter Dickenson and illustrated by Wayne Anderson. It explains everything from flight, the generation of fire to how they mate and reproduce. A must for every dragon owner.

The dragon often symbolized the king or local lord, what is big and powerful and takes your money and your beautiful women? A feudal lord of course.

Dragons are just super cool!

Ancient, extremely intelligent, powerful magic user, fabulously rich, and murderously protective of its possessions. What is the NOT to absolutely LOVE about dragons. Thanks for the article.

With the Ancient Greek dragon, from where poison flowed, the Greeks used the poison from the dragon by legend to coat the arrow head. The Greek word for poison (τοξίνη, or toxini) is where the English language derives the word “toxin”.

I find this genuinely interesting, the way that one mythological figure has been treated, depicted, etc., in different ways. As someone who knew near nothing about dragons, I really enjoyed this article!

The real question is why we keep calling such wildly different creatures of folklore “dragons”.

I just watched an interview with Guillermo Del Toro where he mentioned that dragons are so persistent in mythology because they are a combination of the three apex predators in nature: the serpent, the large cat, and the raptor. I thought that was interesting.

Did not know that! Filing it away in my trivia bank…

The thing is, Dragon is such a loosey defined term in that context. Chinese lóng is really more of a protective rain god / good luck charm. It doesn’t breathe fire or kidnap maidens or lust after gold. In the west, the prince slays the dragon; in china, the lóng symbolizes the emperor. Really the only thing they have in common is that they fly and are vaguely reptilian. You’ll find the same with other dragon anolouges like Quetzalcoatl.

I’ve always loved them. They are amazingly powerful symbols and a wee small part of my brain likes to pretend that they (the fire breathing ones) existed (or exists depending on my whimsy level for the day). They’d be utterly fascinating biologically and environmentally as much as they are culturally.

Peter Jackson’s Smaug is a WOW creation just as the Dwarfs are. Very cartoony and clownish; like pantomime which Tolkien thought very little of.

I’m rather fond of the Space Bat Angel Dragon from Ted Hughes’ The Iron Man. He wants to lick life off the earth, but the Iron Man has a duel with him and the poor dragon has to lie on the sun – twice.

I love the bit when he returns and lands on Australia with a thump and all these jewels pop out of his skin. They have been created by the heat of the sun on his flesh.

He’s my favourite dragon.

Yes, it is interesting that China and places are far west as Wales and Sweden have dragons in their legends and tales… Could there have been a few dinosaurs left at the beginning of Homo Sapiens history, the stories of which have been passed on through the generations? They do look similar to the Komodo Dragon from Indonesia that does have the foulest breath (fiery in fact) to come out of any creature’s mouth on the planet … apart from girls from Beijing of course.

My favourite (sentient) dragon is Kenneth Grahame’s “The Reluctant Dragon”. Charming, refined, unassuming and erudite.

Guards! Guards! by Terry Pratchett remains my favourite dragon related story, the origin behind them and the weaving of the storyline is a great example of Pratchetts genius at creating stories which are both highly comedic, thought provoking and utterly terrifying.

Guards! Guards! and Wyrd Sisters are the two early books in which Pratchett really hit his stride and showed that he had very important things to say about the comedy and tragedy of life, not just about the ridiculousness of fantasy.

Couldn’t agree more.

But in the oldest sources you’ll find them called “worms” . And they live in burial mounds, on top of piles of grave-goods. I don’t think that the dragon is an overly subtle metaphor.

Thanks for a good read. The main problem is that while today’s idea of dragons are remarkably similar across cultures, the earliest versions of these myths described creatures a lot more different from what we have today.

The whole six-limbed giant reptile is a rather modern convergence of a number of different ideas.

Quite a lot of these proto-dragons were merely big serpents.

Apollo vs the Python was one of the prototypes of the European dragonslayer myths and it wasn’t originally about a dragon as we understand it today but merely a big serpent.

The prevalence of similar myths of hero vs. serpent across cultures in Europe and Asia has led people to suggest that they come from a single original myth.

We do see a lot of snake like mythical creatures in a variety of cultures. Usually these creatures are considered evil, and something to be feared. In some cultures, they’re considered to be good, though usually also something to be feared in the original sense of awesome.

There’s a theory that humans have developed a variety of instinctual fears of potentially venomous animals like snakes and spiders that may require quick reflexes to avoid. These kinds of innate fears might explain why a number of mythological creatures seem common across cultures, including something like a serpent or dragon.

True, especially concerning serpents. I actually did a whole project on serpent symbolism/serpents in culture during college. My favorite part was finding out that in Celtic culture, the serpent was originally a more benevolent creature (I’m Scots-Irish).

I feel the exposing of Dinosaur fossils over the ages and across the planet instigated the Dragon myth.

In Scotland, a land with the Unicorn as it’s national animal, surely we have the closest thing to a real life dragon, currently hiding out in Loch Ness?

I have a red lion tattooed on my arm that says different.

I once had to explain to a guy that it wasn’t Welsh though. He couldn’t ell the difference between the lion and the dragon.

I’d definitely say that the Indians and North Americans have the coolest designs in terms of their dragons. However, I enjoy the myths of the east and Norse quite extensively so overall, everyone has their own uniqueness.

This was really cool. I especially enjoyed the sections on Eastern dragons, and the mentions of dragons in the Bible and Torah (it’s not something evangelicals get a ton of exposure to, probably because of translation conventions, the image of the dragon as a fantasy creature, and so on). The discussion of the Chinese dragon’s many different parts actually reminded me of discussions of creatures in Daniel and Revelation. They aren’t dragons per se, but some of them either have dragon-like features or are compared to dragons. Other times, dragons are mentioned without a whole lot of detail (ex.: the dragon the woman of Babylon rides–what or who is it? What does it look like? Should the interpretation of it be more literal or figurative)?

One theory of why dragons are global is that legends of dragons came from seeing the bones of dinosaurs, and imagining giant lizard creatures that left those bones behind.

The baby dragons in Game of Thrones were so cute. Probably less so when they grow up.

Who doesn’t love a baby dragon? 🙂 Baby or adult, I also enjoy the dragons in the Harry Potter universe, because there are so many different species and features. For instance, the Swedish Short-Snout breathes blue flame, the Chinese Fireball lays gold eggs, Peruvian Vipertooths have been known to eat humans, etc. But I think my favorite HP dragon might be the Common Welsh Green. It feels more “classic” and in line with my love for all things British Isles/Medieval. Chinese Fireball is a close second b/c of the beautiful red coat and gold eggs, and b/c it reminds me of Mulan.

Chinese civilisations are pretty old, their dragons may well have been passed down from long before written records. The western notion of dragons as evil could possibly be some sort of deep rooted reactions and metaphors ingrained into legend for past clashes between eastern and western civilisations going back millennia.

I dont think traditionally the chinese have such a Biblically inclined good vs evil view of the world.

The dragon is probably derived from mythology that has grown around the celestial visits of frightening ‘fire-breathing’ comets in the sky.

Great post.

A perfect article, from start to finish! Kudos.

The dragon is probably the most well known mythological creature, I always forget that they exist in the myths of cultures outside of China and Europe. Great article.

It is interesting how you have looked. At the different traditions of dragons in the east and west and there is some implicit discussion of cultural differences as well.

Thinking about how cultural, historical and geographical differences are emulated in the Dragon mythology, both through time and then through cultural values is an interesting next step to your thesis.

The development from serpent to dragon (and in biblical studies back again) and from goddess to monster is emblematic of social changes within societies in the west.

Tolkein was greatly influenced by Beowulf, too! His idea of a dragon probably had shared English/Nordic characteristics.

Nice article. It left me wondering about the concept of “dragon”. Given that there are so many mythical dragons across so many different cultures, I would say the idea of a snakish powerful entity is very well rooted into Human imagination, but I wonder if calling the Eastern beings “dragon” is a matter of syncretism.

Wonderful read, really good work! Everyone knows their own country’s relationship with the concept of dragons, and other similar mythical lore, but reading about the differences is super interesting too!

In the Indian Tantric tradition, the serpent symbolized “Kundalini Shakti”, the divine feminine intelligence behind the creation of the multiverse. (Many Sanskrit words don’t translate properly into English) However, my main point is that the serpent, snake ,and are images found throughout world civilization, because they symbolize the spiral path which subtle energy flows through during creation. The best example is the double spiral shape of human DNA, spiral galaxies, conch shell.