Edgar Allan Poe: Unknown Horrors

Fear and horror take many forms. The variety of accepted phobias, movie monsters, and real-life tragedies can speak of this. A madman brandishing a weapon or a snarling beast is a clear, direct danger–distinct from this, and possibly more frightening, is the nagging anxiety of a pitch-black corridor that demands your presence.

That anxiety originates in a fear of the “unknown,” with whatever danger being present, possibly, but somehow out of sight and even comprehension. When something–a person, an idea, a place, a situation–cannot be easily understood or explained, a feeling of anxiety grows. What follows varies: curiosity, surprise, anger, or sadness. Regardless, the “unknown,” no matter its form, confronts and challenges us, wherever we might go. The unknown–the things that cannot be easily explained–ignites primal, innate fears, pushing us to confront the intangible or flee from it and risk never truly understanding it.

This basic element of the “unknown” plays a crucial role in the works of Edgar Allan Poe.

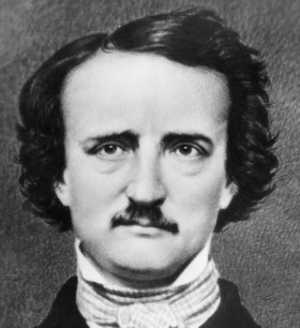

Poe is a cornerstone of American literature, in spite of his short life (1809-1849). Published in magazines and newspapers in his lifetime, Poe’s short stories and poetry have gone on to define the horror short story and the poem in the American literary context, and, over a century and a half after his death, his work is still read and quoted. The events and images in his most famous works, including “The Raven,” “The Tell-Tale Heart,” and “The Cask of Amontillado,” are recognized and repeated in literature and pop-culture. The likes of Charles Baudelaire, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Ray Bradbury, fellow authors, praise Poe as an inspiration. Several notable works outside the literary field, including film adaptations and even pop music album (The Alan Parsons Project’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination) can further prove Poe’s influence.

Moreover, his strongest works would not be as enduring if not for his use of the “unknown” as a story element. The concept of “unknown,” of the unseen, the ambiguous, the stuff that can only be realized in the realm of the imagination, though common in literature, is especially pertinent to the effect of Poe’s work, especially his short stories of horror. This concept of the unknown in Poe’s storytelling originates partly in the philosophical and cultural fixtures of the early half of the 1800’s.

Romanticism: Faith in the Unknown

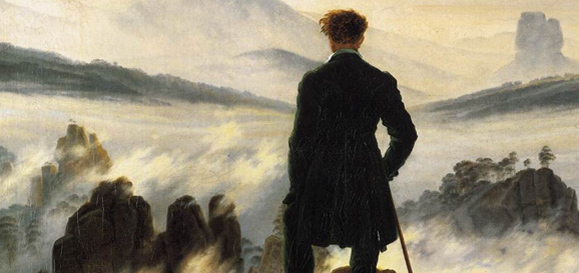

During Poe’s lifetime, a new way of understanding and defining the world–dubbed Romanticism–had been growing in popularity and notoriety in the United States. Originating in Europe, Romanticism acted as a rebuttal to the ideological tenets of rationalism. To put in short, rationalism was a product of the Enlightenment, a broad era predicated on the concept that knowledge could be amassed individually on individual merits, rather than on dogmatic assumptions.

Rationalism takes a vein of thought in Enlightenment thinking further, asserting that the nature of things can be understood by way of logical deduction. In other words, a method can be used to understand the reasons behind a given subject’s existence or nature. The “scientific method” grew from the theorem of rationalism, for example. At the same time, empiricism, the theorem of thought where the best understandings of the world are based on firsthand experience, also became the face of established intellectualism.

This frame of thought came to define a new generation of expert thinkers, with established universities basing education criteria upon it. As the 1800’s approached, however, a new generation of thinkers pushed back against the ideals behind rationalism and empiricism, under the umbrella term of “Romanticism.” Championed by the likes of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, Romanticism sought to place the concept of “knowledge” away from empiricism and rationalism. To Romantics, those that subscribed to Romanticism, humanity was worse off for placing the whole of “knowledge” in what can be seen, rather than what cannot be seen, or, put another way, in sensation.

The American branch movement, though comprising a variety of thinkers and artists, was defined by a singular desire to explore, as a base of wisdom, the “internal world” of the thoughts of humanity, or the imagination. For American Romantics, per Jennifer Hurley, the path to true “enlightenment” was marked not by empirical expertise but by individual introspection (imagination) and abstract ideas. Nature, that which was separate from centers of 19th Century American industrialization, was held up by Romantics as the “inherent possessor of abstract qualities,” qualities that held true wisdom and were not accommodated by contemporary city structures. 1 Emerson, a prominent literary figure in Romanticism and American culture in general, spoke ill of what he considered the “sluggard intellect” of the United States, as well as an overemphasis on “mechanical skills.” 2

For Emerson, America, as a country with its own unique cultural identity, was risking its intellectual health on pursuing hard science; the greatest form of “enlightenment” could be found by way of the imagination, where complex ideas, unknowable to science, could find fertile ground.

Romanticism offered a way to legitimize lofty ideas that cannot be defined by way of empirical rationale, or, in other words, make room for certain “unknown” elements. Poe, counted among the American Romantics, sought to spread the movement’s lofty ideals.

For Poe, again from Hurley, humanity had made the error of ascribing to scientific reason and the rational as the primary sources of worldly wisdom, rather than “poetic intuition.” Spirituality and imagination were endangered by the reliance on empirical expertise, which led, invariably for Poe, to materialism.

Like fellow Romantic authors and thinkers, Poe sought to make room for mystery and the unknown in a world that, to him, was becoming over reliant on the tangible and observable to create a sense of understanding. It is likely not a coincidence that one of the first compilations of his work was entitled Tales of Mystery and Imagination. This Romantic sentiment, a product of its time, filters into Poe’s work, paving the way for many cases of mystery and ambiguity.

Poe makes his distaste for empiricism and literal science clear with his “Sonnet — To Science.” Framed as a soliloquy in mocking praise, Poe dismisses Science as a “Vulture, whose wings are dull realities,” living to “[prey] upon the poet’s heart” and remove famed figures of myth and the arts from their place in the Romantic ether:

“Hast thou not dragged Diana from her car?/ And driven the Hamadryad from the wood/ To seek a shelter in some happier star? Hast thou not torn Naiad from her flood/ The Elfin from the green grass, and from me/ The summer dream beneath the tamarind tree?”

In short, the mysteries of life, the primary source of inspiration and wisdom (in the more traditional sense) are, for Poe, endangered by endeavoring to define all that can and cannot be seen or understood in specific, empirical terms.

Perhaps the strongest example of direct Romantic thought in Poe’s tales of horror lies in “The Colloquy of Monos and Una.” The setting of the tale is the afterlife; our characters, Monos and Una, two former lovers now in the afterlife following a worldly apocalypse. The short story comprises primarily Monos’ account of his death as told to Una.

However, the preamble to Monos’ recounting is a tale of a humanity that doomed itself by way of neglecting Romantic values. Prior to the end, mankind had abandoned “the poetic intellect” in favor of “knowledge,” in the empirical sense. The world before the end, as described by Monos, has been choked by a network of cities that tarnish “Nature”(with a capital N). The last generation brought about the end of the world due in large to its apathy to imagination and contemplation on brought Romantic practices.

The recounting of Monos’ death is heavily detailed, with Monos discussing how it was both painful and not, how he was aware of the surroundings of the place where his “dead” body was laid in wake. From one point of view, Monos’ account could be antithetical to his Romantic leanings, seeing how Poe appears to be explaining the sensations of death, even though death is unknowable to the living.

However, before Monos begins his monologue, Una, before asking Monos to inform her, utters these words:

“In Death, we have both learned the propensity of man to define the indefinable.”

With these words, Poe covers his thematic bases–though his character Monos explains the nature of his death, he also establishes, through Una, the impossibility of “defining” something like death, an inherently unknowable sensation. With this statement, Poe informs his audience to take the account with a grain of salt and a spirit of imagination, rather than accepting Monos’ account as empirical fact.

In another story, “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar,” we see a man, the titular Valdemar, hypnotized at the exact point of his death, as an experiment. The effect of this hypnotism is revealed gradually, in grotesque detail: even as Valdemar’s body decays, his consciousness lingers within the carcass, causing him no end of suffering. Not unlike Mary Shelley’s disdainful view of Dr. Frankenstein’s endeavors, Poe’s Romantic leanings can paint M. Valdemar’s case as one disavowing questionable experimentation. Their desire to subvert a more natural element of life leads to Valdemar’s continued suffering.

Poe’s disdain for materialism, a Romantic vein, can be seen in “The Masque of the Red Death.” In said tale, a plague seems to take on human form and invades the party of a callous, hedonistic nobleman and brings to a deadly end the festivities. Described as a “madman” by the narrator, this nobleman and his patrons are understood as lecherous for withdrawing from the tortured public, wracked by the titular Red Death outside the abbey, to engage in revelry and self-indulgence from (supposed) safety. The party’s demise speaks to the dangers of assuming one’s safety, in any case, and the cold comfort of social class and material possessions.

Indeed, Romanticism arises in Poe’s work in these more obvious forms. However, the Romantic ideals–where more space is allowed for the unknown and the imagination–arise in more subtle ways in Poe’s tales of horror.

Unity of Effect: Space for the Unknown

Romanticism provided major structure for the “unknown” in Poe’s work. However, at a more personal level, Poe developed a model for storytelling that allowed for mystery and intrigue.

Writing in a review of Twice Told Tales by Nathaniel Hawthorne, a fellow Romantic author, Poe outlines his views on what makes the short story (or tale, as he dubs it) an effective medium. Poe emphasizes the concise nature of short stories as their major strength–more specifically, he states that a short story is “not to exceed in length what might be perused in an hour” to achieve the highest effect in a reader. Additionally, and more to the end of the unknown, Poe describes a “unity of effect,” his technique for developing arresting tales, that he asserts Hawthorne fulfills. 3

“Unity of effect,” in short, refers to how a singular effect acts as the major center-point or thesis for a short story’s effect on a reader. For Poe, it is more pertinent for an author to establish a single tone for a tale, then drive this tone throughout for the reader. The internal sensation of this effect can be achieved with a “continuity of effort,” where a “duration” of some intangible sensation throughout the course of the tale stirs the soul.

In his article “The Philosophy of Composition,” Poe elaborates on the unity of effect in his own writing process. Poe establishes the structure inherent in his writing of the seminal “The Raven,” a tale of a man’s tormenting by the titular bird’s repetition of the term “Nevermore.”

Poe explains how, at the outset of writing a tale, he defines and applies an intended “effect” on readers:

“Keeping originality always in view…I say to myself, in the first place, ‘Of the innumerable effects, or impressions, of which the heart, the intellect, or (more generally) the soul is susceptible, what one shall I, on the present occasion, select?;'” 4

The central idea mentioned and enforced in the unity of effect is “repetition”; the emphatic return to key ideas and terms throughout “The Raven” and his other tales. However, another fixture in his writing he mentions frequently in both his review and “Composition” is the limit in time and content related to the short story. Poe asserts that the unity of effect finds its strength solely in the tale and poem because of the necessity of a single reading period. The novel, a much larger quantity of written words, requires (for Poe, at least) more than one sitting for its qualities to be fully absorbed by the reader. In other words, the novel requires more time and sessions dedicated to it, so its effect can never be a strong as the tale or the poem.

Length of reading period dictated the power of effect Poe’s tales had on his audience. This in mind, the repetition of theme and sensation (the raven’s “Nevermore,” the heartbeat of an old man, as examples) were of primary concern in terms of what is on paper. This focus of Poe’s written words creates another effect in readers: that of mystery. What is not pertinent to the effect of the tone is left uncertain and to the imagination of the audience.

Though Poe endeavored for the artfulness of his tales, the “unity of effect” is as much a product of economy, of detail and monetary need, as Romantic design. Jill Lepore, writing for the New Yorker, asserts that Poe, who was frequently impoverished in his relatively short life, wrote to live, not merely to promote the Romantic ideals. Moreover, Lepore suggests that Poe’s truest passion was his poetry; the horror tales were more so a means to an end, that of making money in a world beset by recession and economic panic. To her end and credit, she cites a written account from Poe, where the writer establishes how “The Gold Bug,” a tale of adventure rather than horror, and “The Raven” were both written for with money in mind. 5 This in mind, the unity of effect takes as much advantage of the audience Poe was writing for, seen by Lepore as one that would not discern between a good horror tale and a bad one.

However, this economic reality need not induce readers to dismiss Poe’s artistic efforts. An artist’s body of work is a varied thing, with certain examples being more affecting than others. Poe is no exception. There is likely a deeper reason that certain works, such as “The Raven,” are remembered and continue to grip audience interest even as other works like “The Gold Bug” may not.

Through the application of the unity of effect, Poe’s focus on a single feeling to engage his audience allows space for the unknown; with all other information that would build the characters or setting being dashed for the “unity,” tales such as “The Raven” are permitted to live in an ambiguous middle-ground that tickles viewer interest. Much of that poem’s power comes from the uncertain nature of the narrator’s mental health. Is the titular bird a harbinger of ill news, that he will never meet his “lost Lenore” again? Or is that “prophet” nothing but a bird repeating the same word incessantly, and the narrator’s anxiety and grief cause him to read messages that are not really there? It is unknown, and that is a crucial element of horror in “The Raven.”

Unreliable Narrators, Unknowable Narratives

Poe is particularly noteworthy for his frequent use of anonymous narrators as the audience’s point-of-view into his settings. This storytelling setup is present in many of Poe’s tales of horror; to name a few, “The Raven,” “The Tell-Tale Heart,” and “The Black Cat.” The sheer amount of nameless focal characters across so much of Poe’s individual works is likely not a coincidence, as the important use of repetition to unity of effect would attest.

The use of ambiguous narrators can easily be read as an emphasis on the unity of effect and the innately mysterious nature of Poe’s stories. Typically, an anonymous protagonist acts as a “blank slate” for any reader to project their own identities upon.

However, Poe’s protagonists, though many of them are nameless, exhibit some unique traits that make audience projection difficult; they are not meant to be “you,” in other words. Conversely, their frequent lack of names alienates the audience. Even in cases where they are named, such as “The Cask of Amontillado” or “William Wilson,” much of their immediate background and identity are left in question.

Many of these characters are placed in narratives where the proceedings are inherently ambiguous. Since many of these nameless narrators are in states of mental unwellness–some of them, such as our narrator of “The Tell-Tale Heart,” speak openly to being “mad.” In these cases, the nature of their respective stories is in doubt. James W. Gargano, writing for the National Council of Teachers in 1963, argues as much; Poe’s stories, per Gargano, are crafted to emphasize the limited scope of the primary characters. 6

When the point of view is so skewed, the proceedings of a tale cannot be easily accepted, and audiences are left in a tense uncertainty This is partly the mystery of Poe’s work.

Theories: Engaging With the Unknown

This “unknown” fixture, like in the Romantic case of “Monos and Una,” is established clearly in many of these stories. In “The Tell-Tale Heart,” the narrator, speaking (presumably) in a court of law, espouses how they had slight reasons for killing the doomed old man.

“It is impossible to say how first the idea entered my brain; but once conceived, it haunted me day and night. Object there was none. Passion there was none.”

The narrator, seemingly finding no profound reason for the grisly murder, asserts:

“I think it was his eye! Yes, it was this! He had a vulture eye–a pale blue eye with a film over it.” Whenever it full upon me, my blood ran cold; and so, be degrees…I made up my mind to take the life of the old man, and thus rid myself of the eye forever.”

Their rationale seems nonsensical, proof of their own madness despite claims to the former. Why would an eye, however unnerving, be a proper motivation for murder? For Poe, it seems the reasoning does not matter; the “unity of effect” demands the focus on the emotional response of the audience, in this case to the anticipation in the murder of the old man and the confession of the narrator. The motivation behind it is left uncertain, a mystery to the audience and likely the mad narrator.

These mysteries, though possibly meant to confound, have invited readers to impress deeper readings. One such academic crafted a feminist reading of “The Tell-Tale Heart” that casts the tale in a new light. Gita Rajan penned an essay applying feminist theory to the story, opining that the first-person narrator can be read as female, rather than male.

She elaborates that the typical view is that the narrator, understood as male, desires power over the father-figure old man; Rajan reasons that the narrator can be understood as a woman, and the “vulture eye” as a symbol for the objectification of women. 7 Read this way, “The Tell-Tale Heart” becomes a tale of a woman’s attempt to escape being an object of desire by a male society.

Similarly, theories related to class struggle have been developed around “The Cask of Amontillado.” Elena Baraban breaks one such theory. In story, it is left uncertain what was Fortunato’s “insult” that motivates Montresor to murder him. Baraban, citing other authors and her own sensations, suggests that class distinctions between the two men may define the insult in question.

During the descent through the catacombs to Fortunato’s fate, Montresor notes a Masonic symbol, representing his forgotten family’s name. Baraban pinpoints this segment as evident of class tension between the two men. Montresor is a member of a family with prominence that, over time, has fallen into obscurity, hinted at by the Masonic symbol. Fortunato’s inability to recognize said symbol and additional aesthetic elements in his design (his “fortunate” name and jester’s mock) are interpreted as casting him as “new money,” in contrast to Montresor’s now-outdated family. In short, Baraban suggests that the “insult” Fortunato makes to Montresor is one of class etiquette. Read this way, Montresor’s ghastly act against Fortunato becomes a violent class struggle where the old guard violently subverts the new classes. 8

These two theories capture the essence of Poe, that is, the mystery of his tales. With the unity of effect employed, the audience is allowed more space to ruminate on the broad strokes of these and other tales. Indeed, Rajan and Baraban’s essays are merely the tip of the iceberg for theories and speculations on the nature of Poe’s tales. A web search can turn up a plethora of digitally published resources concerning hidden meanings behind and potential readings into Poe’s oeuvre.

Interpretive views on the ambiguous elements of Poe’s tales are a major testament to Poe’s longevity. Not unlike adaptations and reinterpretations of Shakespearean drama, postmortem takes and views on Poe allow his tales to stay alive and persist unto today. Without new contextual views on Poe, he would be truly dead and unknown in the worst way.

Psychology: Defining the Indefinable

Those psychological theories on Poe’s work have a particular relevance to Poe’s era. The concepts that fall under the umbrella of psychology (mental illness and wellness, insanity, neuroses), were topics of discussion by the general public and choice groups of fledgling expertise. Though the earliest school of psychology would not be founded in the U.S. until the 1890’s, the former half of the 19th Century was dotted by social frenzies and debates around the nature of the “insane” and “neurotic,” and Poe was keen to mine the subject matter for inspiration in his work.

Much of Poe’s text in his horror tales establishes how his focal characters, their first-person perspective being the audience’s window into the proceedings, are unreliable, making wholesale acceptance of their accounts difficult. It can be easy to read these clouded perspectives are ailing from any variety of psychological ailments, from specifically defined disorders to generalized issues.

Caroll Dee Laverty writes exhaustively on Poe’s relationship with psychology, with particular focus on the prominence of mental processes in Poe’s literary works and his personal writings to publishers and friends. Poe speaks on the necessity of designing written works with the emotional response of the reader in mind, a necessary element of his “unity of effect.” Laverty argues this composition effort predates and arguably predicts the psychiatric profession, where the fears and anxieties are given a voice and critical review, many years before its formal definition. A Henry Sigrest is cited as attributing the psychiatric theory to study of the effects of literature, making the connection to Poe, albeit indirect, all the stronger.

The treatment of those deemed “insane” was far from the (soft) science it is today, and the diagnosis and treatment of those with mental illnesses and conditions is still highly suspect from the public today. Poe’s era was rife with such discussions, and he capitalized on one such alternative to treating the “mad,” the soothing method, in his tale “The System of Dr. Tarr and Professor Fether,” a rare tale of (dark) humor from the macabre Romantic.

The soothing method would see an asylum inmate treated with little to no restraint, allowing them more freedom of travel and physical agency within closed quarters. In Poe’s tale, a nameless narrator encounters an asylum where, in a twist, the inmates are allowed to manage the business while the experts and employees act and are treated as the mad. The tale, like Poe’s other works, can be read as an indictment of the soothing method as overly lax, or as a satirical take on the very nature of madness (for the time). Nonetheless, as Laverty asserts, the tale is proof that Poe was more attuned to the fledgling school of psychology than were many authors of his era. 9

As Laverty affirmed in the mid-1950s, many writers have found and forwarded intriguing correlations between recognized conditions and Poe’s storied occurrences throughout the ensuing decades. Writing for this site, Kevin Mohammed discusses “The Fall of the House of Usher” and the correlation between the vague ailments of two characters and defined, real-world conditions. In the tale of the last heir to great family name in-decline and his terminally-ill sister, the titular Roderick Usher is wracked by a keen sensitivity that impedes his daily routines (such as they are) and an obsessive need to micromanage his sister, Madeline. Mohammed points out the similarities between Usher’s behaviors to recognized (if not contested) conditions, hyperesthesia and hypochondria. 10

At least two writers find Poe’s emphasis on what he called “perversity” to align eerily with a contemporary psychological concept. In both The Tell-Tale Heart and The Imp of the Perverse, Poe’s narrators commit a murder and appear to be largely cleared of any suspicion. Yet, when confronted by intolerable internal pangs (the “beating” of the old man’s “hideous heart” in Tell-Tale’s case), they break down and confess their murders, with seemingly no outside catalyst to do so.

Chinelo Nkechi Ikem correlates this common scenario in these stories to a recognized psychological phenomenon, “intrusive thoughts.” Intrusive thoughts, recognized as affecting 90% of otherwise undiagnosed individuals, involves a pattern of recurring thoughts that seemingly has no immediate external trigger. In addition to its commonplace occurrence in the public, Ikem states how this pattern can involve thoughts both positive and negative, the latter aligning with Poe’s focal characters in Tell-Tale and Imp. Moreover, she establishes how “The Imp of the Perverse” is used colloquially to refer to this phenomenon, a clear influence that Poe has had in understanding choice conditions outside the profession. 11

For Poe, those “perverse” thoughts were “unknowable,” an affliction with neither diagnosis nor alleviant. Ikem moves towards diagnosing “perversity” with the knowledge of modern psychology, and, thus, giving more concrete form to the ambiguity that haunted Poe.

Mark Canada and Christina Downey, writing for The Conversation, also discuss Poe’s perversity, adding further context to Ikem’s writing by relating the “imp” in the works to the author’s life.

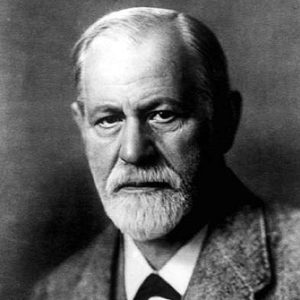

Canada and Downey correlate Poe’s understanding of the perverse–an innate, unsuppressable desire to commit choice behaviors, even in the face of undermining one’s immediate or long-term happiness–with the Freudian concept of the “death drive.” Freud forwarded the theorem of thought that thoughts and feelings undesired by those that experience them are repressed into the subconscious. When unmanaged, these internal sensations and ruminations manifest in ugly ways, primarily in irritability and insecurity. Another way that unconscious thoughts take form is the “death drive,” whereby the afflicted will seek out destructive behaviors as an unconscious method to alleviate the tensions of their subconscious pains.

Canada and Downey cite chemical dependence on alcohol, specifically drunk driving, as one such example of this type of behavior. Furthermore, they forward contemporary studies of the brain asserts how the general makeup of the “prefontal cortex” (the most forward-facing area of the human brain) can often determine an individual’s ability to positively or negatively manage external complications of life. Though Poe lacked the knowledge of both Freudian mechanisms and the empirical knowledge of brain function, Canada and Downey forward Ikem’s assertions that Poe was hitting at such knowledge through his writing. 12

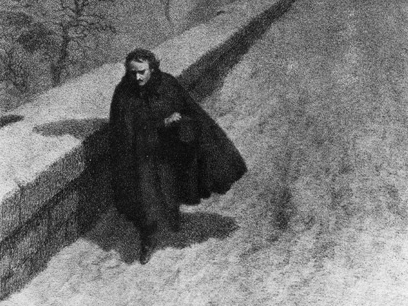

Certainly, alcohol dependence was a major element of Poe’s life; James Albert Harrison, writing in a comprehensive biography of Poe, speaks frequently of Poe’s destructive substance abuse, as well as seemingly impulsive behaviors that had little impetus or positive outcome in the author’s life. Poe was excluded from his adoptive father’s will for his ill-repute in early adulthood, and his negative dealings with fellow authors (he was a relentless and unsparing critic) made him a pariah in many literary circles. Even after his death (still shrouded in uncertainty), Poe faced the ire of publishers and authors eager to mar his name and artistic capabilities. Harrison asserts from the outset of the biography how much of Poe’s life and reputation are in question, due to not only vindictive literary circles but also Poe’s pension for exaggeration and fabrication. 13

Much of Poe’s life had been lived “as a dream,” with seemingly little thought for the distant future. Canada and Downey’s greatest suggestion is Poe’s pension for the “unknown” being a product of undiagnosed anxiety, casting Poe as an unwitting soothsayer for the all-too modern culture of burnout.

Poe’s works, with their fostering of the “unknown” as a theme, are particularly eligible for a Freudian theoretic review. Psychoanalysis, as a school of thought, emphasizes the importance of unseen impulses originating in the unconscious mind, the bane of that which we would rather neither face nor embrace. Poe saw his modern world as negligent of the realm of the imagination, a concept that can be correlated to Freud’s unconscious. The shortcoming of society, for both, could be understood as the shunning of basic but pivotal principles–the Romantic sentiment for Poe, and the early developmental drives for Freud. The death drive is already seen in Poe’s works, but other concepts can be linked.

The significance of dreams for the purpose of greater understanding is shared by both men. Poe’s works and writings speak frequently of the mysterious allure of dreams, and of their potential to unlock greater wisdom. He states as much for the act of daydreaming:

“They who dream by day are cognizant of many things which escape those who dream only by night.”

One poem ponders the nature of man’s perception of existence, “A Dream Within a Dream,” where the human tendency for security is possibly dissuaded in favor of living and understanding life as a dream. This belief grows from Poe’s particular beliefs on the need for exalting the imagination. For Freud, dreams were a prime realm for alleviating human suffering. Freudian dream interpretation is key in psychoanalysis for understanding an individual’s subconscious identity and insecurities. This, in turn, could prove a particular hangup or traumatizing event that the individual did not consciously consider. With the resonance of the artistic movement surrealism, which hinged its aesthetic purpose on dreams and the unconscious, Poe’s work can be said as a progenitor of how dreams are frequently viewed and understood.

One other Freudian concept holds particular bearing on readings in Poe’s works and the “unknown” within them: the uncanny. Known in the original German as “unheimlich” or “un-homelike,” Freud defines the uncanny as something familiar taking on an unfamiliar sense. Freud uses the example of waxwork figures to illustrate this psychoanalytic phenomenon. While these figures can, from choice angles and distances, appear like genuine humans, further examination will reveal them as forgeries. The feeling of unnerve that follows, the uncertainty that suggests these shapes could come to life, is the uncanny. Discerning Freud’s at-times dense thought-process, the uncanny feeling grows from an infantile developmental struggle to limit what is seen to its core, per an individual’s understanding. The uncanny arises when such views are (seemingly inevitably) dashed, resulting in morbid subconscious tension and external fear. 14

Freud, continuing in his essay on the concept, states how stories that forward an uncanny impression never fully establish a madness innate in the focal character; this situation would fully rationalize, in the typical sense, the events of the story and the uncanny would fall away from the proceedings. For Freud, the ability to distinguish the events as “real” or “unreal” is antithetical to the uncanny. Poe’s tales of horror, notably The Tell-Tale Heart, The Raven, and The Fall of the House of Usher, bear the “supernatural” element where key events exist in a halfway house of legitimacy, where the fantastical may be nothing more than the fancy of skewed mental state. The “unknown,” in that sense, correlates almost precisely with the “uncanny.”

Almas Sardar elaborates on the Poe/Freud intersection with further citations of expertise and illustrative examples. Poe’s works are rife with the potential for the “uncanny,” with the frequency of mundane objects being cast in new, unnerving ways. Sardar unpacks this effect in “The Raven’s” titular bird. Is the raven a “prophet” foretelling doom for the narrator’s hopes of reunion with Lenore, the very Lenore reincarnated, or merely a chattering bird? Poe gives no clear answer, and this is the nature of the uncanny; not only is there uncertainty, but there is also the suggestion of the bird’s transfiguration, or to its being something other than a mere fowl.

Similarly, elements of the uncanny arise in “The Fall of the House of Usher” and “The Tell-Tale Heart.” The titular Usher manor is given human-like traits, giving potential to the idea the house itself is a living entity, reflective of the moribund siblings inside. The narrator of “Tell-Tale” speaks incessantly of the “vulture eye” of his victim. Psychoanalysis holds the loss of vision as a core fear in the infantile stage of development, where the uncanny effect finds its root. The theme of double identities, where two individuals share the same appearance, is keenly uncanny. Poe also addresses this phenomenon in his “William Wilson,” where the titular man is constantly mirrored by a man looking exactly like himself. At the tale’s end, Wilson’s murder of the double is seemingly revealed by the doppelganger as metaphysical part of Wilson, and that he has “murdered himself.” Ambiguity over the nature of the double and the suggestion that someone who happens to look like you may be a part of your identity align the tale eerily with Freud’s ideas and Sardar’s elaborations.

Notably, Sardar relates the “unknown” elements of Poe’s tales to a Russian literary concept, “defamiliarization.” This suggests that Poe’s technique in horror has grounding beyond his own language, making his penchant for the “unknown” all the more prescient. 15

It is largely left to conjecture if Poe had any direct knowledge of psychology that would be directly comparable to the profession or application thereof. Psychology and Freudianism, However, it is not far-fetched to reason that his work correlates with the broadly-defined psychological and psychiatric concepts, and the seeming prescience of Poe’s tales in regards to the tug of unseen psychological forces.

World of Uncertainty: The Time of Poe

Capturing the behavior of individuals pulled along by forces outside their conscious control, be those forces “unknowable” and “indefinable” or comprehensible and preventable, may have been a deeply personal dilemma for Poe.

Lepore, aiming to contextualize Poe within the culture and politics of lifetime, establishes Poe’s frequently destitute living standard. Though Poe may have written for the sake of the Romantic and the sheer art of it all, he needed to make money to survive. This endeavor proved difficult, for Poe and much of the United States’ population in the early 19th Century. The former half of the 1800s was a period marked by financial uncertainty, with the policies of Andrew Jackson (U.S. president, 1929-1937) casting the value of the dollar and the stability of the nation’s banks into chaos. These economic moves resulted in the Panic of 1837, resulting in a seven year depression and overall economic uncertainty in a variety of fields, including that of the publishing business.

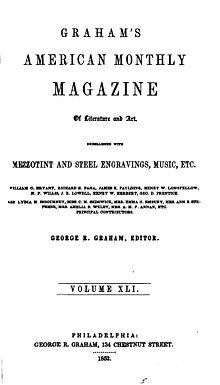

Poe was not exempt from these financial realities, and Lepore reasons that Poe’s move to the “Gothic,” or horror, was motivated by market appeal research more so than his Romantic sympathies. Poe’s work and literary criticism were published in a variety of magazines and periodicals, including The Southern Literary Messenger, New York Daily Mirror, Graham’s Magazine, and The Saturday Evening Post, and his star led him from his native Boston to Philadelphia (where his most prolific period of published writing took place) to Baltimore, where his death occurred.

Everywhere he went, his troubled psyche and economic struggle followed. That prolific period in Philadelphia, lasting from March 1939 to April 1944, saw Poe earning $387 dollars from his published work (much of that written was credited as unpaid). 16 17

His time at Graham’s Magazine was particularly noteworthy, as Poe had many of his notable works published in its pages (“The Masque of the Red Death,” “A Descent into the Maelstrom,” “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” and his review of Twice-Told Tales) and, as literary editor, gained his reputation as a caustic critic. Following Poe’s departure and the appointment the new editor, Rufus Grimwolt (an adversary of Poe’s), the publication avoided Poe’s work, notably turning down “The Raven” for publication. Like many publications in the post-Jacksonian recession, Graham’s struggled frequently and folded in 1858, nine years after Poe’s death. 18 Such was the tumult of a frequently toxic literary landscape and an uncertain economy.

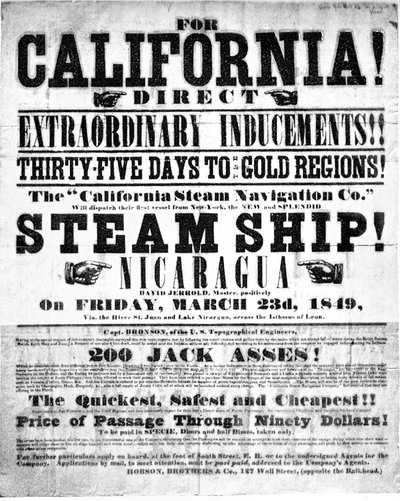

This was the era when the California Gold Rush wrested the interest of ambitious individuals and the ire of Poe. Those with little prospect in mainstream society or an excess of adventurous spirit risked what they had for the slim chance of striking gold and making a fast fortune. This fever had as much rooting in the economic chaos of the post-Jacksonian era as it did the seemingly-inevitable “get-rich-quick” schemes seen throughout human history.

Poe looked at this fever with disdain, stemming possibly from his Romantic notions dictating wisdom as innately founded on the unseen sentiments.

Among his last published poems is “Eldorado,” a melancholic tale of a lone knight in search of the titular, mythical city of gold, only to be met by a “pilgrim shadow” that curtly directs him to the “Valley of the Shadow” to find his prize. The timing of publication corresponds with the Gold Rush’s timeline so as to be read as an indictment of the “fever” for easy riches. Indeed, Poe had some immediate baggage with the Gold Rush, with a personal editor having lost his life on the trip to California. Poe dismissed the Gold Rush pipedream, expressing in a letter his commitment to the literary arts over “all the gold in California.” 19

Additionally, Poe fabricated a hoax in 1849, to draw public attention: the (illusory) meeting of a “Wolfang von Kempen,” a chemist who had discovered a method to transform lead into gold. If taken as truth by an audience, the implication is that gold’s value has plummeted, rendering the Gold Rush all the more empty. Poe, it seems, had a greater purpose behind the hoax than temporary public interest: he sought to dissuade the empty pursuit of “financial speculation,” likely to be replaced by the Romantic faith in that which is “unknown.” 20 The rejection of materialism, though noble, may have likely exacerbated the financial strains facing Poe.

Indeed, though they are his most enduring works and not lacking in nuance and ambiguity, his tales of horror were written and published nearer the end of the short life primarily to earn cash. A Penn Magazine, a dream of a personal body of self-published work for Poe, never materialized, in spite of the fame brought him by “The Raven,” a tale of man tormented by that which cannot understand or explain.

Poe’s life was much marred by that feeling of uncertainty, albeit it was one that all too comprehensible. It could be said that his fostering of “the unknown” was the channeling of the effect of his troubled mind, from plausible mental duress chased by the financial struggles of his era, into his work. The things that cannot be easily understood, how a passionate artist can struggle to find expression or reception, filters throughout the tales.

Cosmic Horror: Influence of the Unknown

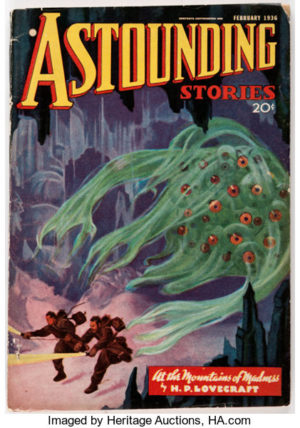

Poe’s brand of the unknown has a vein of influence in literary culture beyond his lifetime. The most notable author to take up much of Poe’s mantle is arguably H. P. Lovecraft. Born Howard Phillips Lovecraft in 1890 and living only to the age of 47 when he died in 1937, the famed originator of Cthulhu and cosmic horror toiled much of his literary career in relative obscurity, described as a writer of “pulp.”

Though not quite a household name (and his supremacist politics will not aid on that front), Lovecraft lives on through a dedicated cult, Arkham House, that publishes his work years after his passing, as well as through the efforts of professional writers and filmmakers who cite his work as inspiration. Though his body of work has more recently been scrutinized for its explicitly white supremacist politics, Lovecraft nonetheless holds a major foothold in modern horror, in literature and beyond. 21

Like those of Poe’s, Lovecraft’s tales of horror avoid the general “bogeyman” structure in favor of broader thematic setup to instill fear. Lovecraft’s particular format goes by the name “cosmic horror.” This subgenre, of which Lovecraft is credited as founder and originator, is defined by a theme of the “indifference” of the universe (or existence, in general) to the existence of humanity. Whereas many horror tales seek out frightening but mostly comprehensible horrors, the monsters and otherwise threats of cosmic horror are representative of the greater threat of a universe that could care less about the fate of humanity. 22

As such, much of the threat in Lovecraft works, such as At the Mountains of Madness, The Dunwich Horror, and Call of Cthulhu, is defined by how incomprehensible it is, to both the human mind and the sense of order in the world during Lovecraft’s time.

Much of this literary thematic structure aligns with that of Poe, in essence if not in fine detail. Though Lovecraft often cast his “Eldritch” monsters in his tales, much of their description is given by unreliable focal characters in the pangs of madness, not unlike Poe’s own oeuvre. Furthermore, Lovecraft’s forwarding of a worldview that eschews mankind’s exceptionalism dabbles in the sense of the “unknown” utilized by Poe.

In his own At the Mountains of Madness, Lovecraft uses choice terms to describe the terrors afflicting his characters. The cast, set on exploring the unknown reaches of the far south, have instead met the trademark Lovecraft monsters, referred to in text as “obscurities” by first-person narrator William Dyer. The limited perspective of how the story is told further obscures those terrors, with Dyer effectively stating that words can do little to explain the horrors of the titular mountains. Dyer also speaks in language that evokes Poe’s views on Enlightenment principles:

“Instinct alone must have carried us through–perhaps better than reason could have done…”

These similarities are not a coincidence. Lovecraft was a profound follower of Edgar Allan Poe. Lovecraft would speak of Poe’s influence on the former’s writing in a number of private letters, but one such letter in particular highlights the importance of Poe’s writing style for the cosmic horror author. Writing to Fritz Leiber, Lovecraft asserts Poe’s preeminence in “basic seriousness and convincingness” in the literary field, emphasizing the “total effect” in Poe’s work, very likely referring to unity of effect. 23

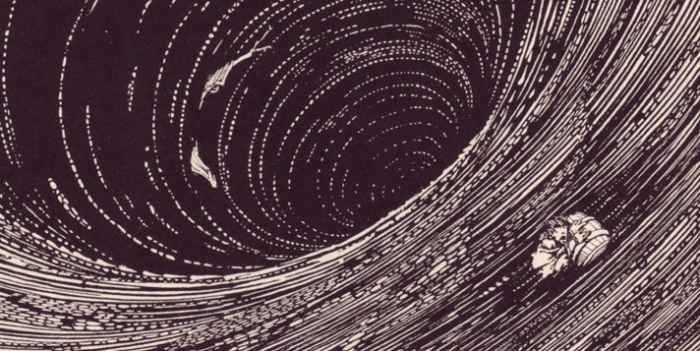

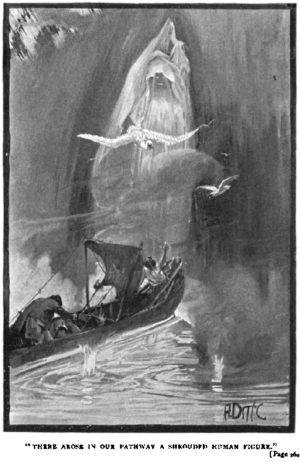

This sentiment filters into Lovecraft’s overall output, but perhaps the strongest link to Poe is between Mountains and Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, mainly in that the latter almost certainly acted as direct inspiration for the former. Notable for being Poe’s only finished novel, Narrative is written as a personal account by the titular Arthur Gordon Pym, concerning three major misadventures on the open seas. Notably, Pym encounters stereotypical “natives,” mysterious natural formations that defy explanation, and a great white humanoid figure, all in course of traversing the realm near the South Pole and with little explicit detail to a from a strong mental image.

Much of Mountains of Madness aligns with the style and setting of Narrative, sharing both setting (the mysterious Antarctica) and thematic concepts. Mountains bears both mysterious beings with limited descriptions and the theme of respecting the danger faced in unexplored regions, with Dyer peppering his account with warnings against exploring the titular mountain range of the Elder Things.

Narrative is more understated, but its references to the seeming incapability of prior seafaring expeditions to trespass upon the South Pole, taken in tandem with Poe’s noted disdain for the Enlightenment sentiments, can read like an indictment of the hubris of man’s desire to “define the indefinable.” In this way, Poe could likely be discouraging this lethal curiosity to pave the way for the Romantic path of enlightenment.

This vein of thought is certainly present, albeit more explicit, in Mountains. Much of Dyer’s writing is dedicated to the incapability of the victims, and potential readers, to comprehend the goings-on at the mountains, from the aforementioned struggle to apply reason to Dyer’s terrifying journey, to the biology and origins of the Elder Things. A found carcass of one such Elder Thing is examined by the expedition’s expert, and the findings fly in the face of generally accepted standards of biology–it uncertain, by those standards, if the creature was just that, or partly or in whole a plant-based organism. The civilization of the beings credited with creating the Elder Thing is described vaguely and broadly, as Dyer finds it too difficult to explain.

This vein of thought is certainly present, albeit more explicit, in Mountains. Much of Dyer’s writing is dedicated to the incapability of the victims, and potential readers, to comprehend the goings-on at the mountains, from the aforementioned struggle to apply reason to Dyer’s terrifying journey, to the biology and origins of the Elder Things. A found carcass of one such Elder Thing is examined by the expedition’s expert, and the findings fly in the face of generally accepted standards of biology–it uncertain, by those standards, if the creature was just that, or partly or in whole a plant-based organism. The civilization of the beings credited with creating the Elder Thing is described vaguely and broadly, as Dyer finds it too difficult to explain.

Other works by Lovecraft forward the philosophies endemic in Poe’s works. In “Call of Cthulhu,” an account of Francis Thurston on the final manuscript of great-uncle and professor of Semitic linguistics George Angell gives way to expounding on the mysterious “cult of Cthulhu,” and the Romantic notions of the “unknown” inherent. Thurston gives personal accounts of the many individuals related to the manuscript by the late Angell, and they corroborate the existence of a primordial cult dedicated to the Eldritch high priest, Cthulhu, of an even older group of beings, the “Old Ones.”

The short story is premised with a narrator giving secondhand accounts from individuals with questionable mental states (considering the effect of firsthand encounters with the cult and their high priest). This limited perspective giving insight into troubled minds casts all proceedings into ambiguity

Thurston admits in the narrative to being incapable of giving full account of the interviewees’ stories. He states as much for his third subject, surviving second-mate Johansen from an expedition whose crew suffered losses following an encounter with the resting place of Cthulhu at sea. Johansen cannot recall all that occured with certainty, and Thurston discloses his incapability (or possibly unwillingness) to sleep from the vaguely-.defined horrors in the manuscript corroborated by the second-mate.

Notably, the choice of simile in the Inspector Legrasse’s account pushes Poe’s Romantic ideal of poetry; Thurston states how “only poetry or madness” could do justice to explain the horrors encountered by Legrasse and his officers in the course of investigating the worship grounds of the cult.

These choices of wording align with much of the sentiments of the unknown as seen in Poe’s work: there are some things in the world that mankind cannot understand. For Poe and Lovecraft, this was impetus to shift towards Romantic intellectualism, which places the imaginative mind as the seat of wisdom.

Michael Cisco, writing on the connection between Poe and Lovecraft, reasons that both authors share the Romantic strand disputing the empiricism of the Enlightenment. Cisco defines the works of both Poe and Lovecraft as “cosmic horror,” where certain events that could possibly be “supernatural” are cast in a way that leaves them ambiguous. Cisco asserts that Poe and Lovecraft executed this by employing limited perspective (through unreliable narrators and general vaguery), while crouching their technique in the frame of Romantic thought. 24

Ultimately, Cisco unpacks how Lovecraft carried Poe’s Romantic notions of the unknown into the 20th Century. With the cult of Lovecraft harboring fans small and culturally significant alike, much of Poe’s understanding of the unknown has been passed down through the 20th Century to the present-day. Though the philosophical framework has shifted from the Romantic to arguably the nihilistic, the sentiment that fear finds its footing in the ambiguous, or the incomprehensible, echoes forth in modern-day horror through the efforts of Lovecraft and his enthusiasts.

The danger with attempting to define the “unknown” in Poe’s horror is that one particular element can be exalted over another as the root of Poe’s relevance. The “unknown” as defined here covers many aspects of Poe’s works, including the method behind intended emotional effect, his choice of aesthetic details, and even the world in which he developed his skills and struggled to survive within. To summarily attribute any one aspect as the pinpoint for Poe’s longevity and appeal is to reduce the cornucopia of interest for potential readers.

The danger with attempting to define the “unknown” in Poe’s horror is that one particular element can be exalted over another as the root of Poe’s relevance. The “unknown” as defined here covers many aspects of Poe’s works, including the method behind intended emotional effect, his choice of aesthetic details, and even the world in which he developed his skills and struggled to survive within. To summarily attribute any one aspect as the pinpoint for Poe’s longevity and appeal is to reduce the cornucopia of interest for potential readers.

Overall, the intent behind elaborating on what this article calls the “unknown” is to unpack the many facets of Poe’s work, within and beyond his choices of words and events that resonate well after his time. This body of effect is easily unified under this idea: there is much that humanity cannot immediately or easily understand, and we must appreciate this fixture. Poe, through his Romantic notions and understandings of fear, appreciated it, as the “unknown.” And, because of Poe’s resolve and craft, we can appreciate his work for years to come, come what may.

Works Cited

- Hurley, Jennifer A. American Romanticism. Greenhaven Press. San Diego, CA, USA (2000.) via the Internet Archive (archive.org). ↩

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “The American Scholar.” American Literature to 1865. Indian River State College Libraries. via Digital Emerson http://digitalemerson.wsulibs.wsu.edu. ↩

- Poe, Edgar Allan. “Twice-Told Tales: A Review.” Graham’s Magazine. April, 1842. Accessed via https://commapress.co.uk/resources/online-short-stories/review-of-hawthornes-twice-told-tales/ ↩

- Poe, Edgar Allan. “The Philosophy of Composition.” 1842. Poetry Foundation. Accessed via https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69390/the-philosophy-of-composition. ↩

- Lepore, Jill. “The Humbug.” The New Yorker, 20 April 2009. ↩

- Gargano, James W. “The Question of Poe’s Narrators.” College English 25, no. 3 (1963): 177-81. ↩

- Rajan, Gita. “A Feminist Rereading Of Poe’s ‘The Tell-Tale Heart.” Papers On Language And Literature: A Journal For Scholars And Critics Of Language And Literature 24.3 (1988): 292-293. ↩

- Baraban, Elena V. “The Motive for Murder in “The Cask of Amontillado” by Edgar Allan Poe.” Rocky Mountain Review of Language and Literature 58, no. 2 (2004): 51-52. ↩

- Laverty, Carroll Dee. “Chapter III: Psychology.” Science and Pseudo-Science in the Writings of Edgar Allan Poe. 1951. Pp. 44-98. Accessed via Edgar Allan Poe Society. Last updated 1 February 2015. https://www.eapoe.org/papers/misc1921/cdl51c03.htm ↩

- Mohammed, Kevin. “The Melancholy of Two Ushers: Into the Mind of Poe.” The Artifice. Edited by Aaron Hatch, idleric, Joe Manduke, Jacque Venus Tobias, Christen Mandracchia, and N.D. Storlid. 5 January 2016. ↩

- Ikem, Chinelo Nkechi. “There’s a Name for That: The Imp of the Perverse.” Pacific Standard. The Social Justice Foundation. Last updated 9 June 2018. https://psmag.com/magazine/imp-of-the-perverse ↩

- Canada, Mark and Christina Downey. “What’s behind our appetite for self-destruction? Edgar Allan Poe might have known.” The Conversation. republished on scroll.in. 16 January 2019. https://scroll.in/article/908751/whats-behind-our-appetite-for-self-destruction-edgar-allan-poe-might-have-known ↩

- Harrison, James Albert. The Life and Letters of Edgar Allan Poe. New York, New York: T. Y. Crowell & Co., 1903. Accessed via Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/lifeletteredgarall01harrrich/page/n8 ↩

- Sigmund Freud, ‘The “Uncanny”’ [1919], in The Complete Psychological Works, Vol. XVII (London: Hogarth Press 1955 & Edns.), pp.217-56. [trans. Alix Strachey, in Freud, C.P., 1925, 4, pp.368-407]. ↩

- Sardar, Almas. “Poe’s Unity of Effect and the Uncanny.” English Language and Literature Dissertation, University of Westminster, July 2019. SCRIBD. https://www.scribd.com/document/416346061/Poe-s-Unity-of-Effect-and-the-Uncanny ↩

- “Poe’s Most Productive Years.” National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Last updated 22 September 2017. https://www.nps.gov/edal/learn/historyculture/timelines-mostproductiveyears.htm ↩

- Dameron, J. Lasley. “Edgar Allan Poe: 1809-1949.” Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. edited by Charles Reagan Wilson and William Ferris. University of North Carolina Press, 1989. Accessed via “Documenting the American South.” UNC-Chapel Hill. https://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/poe/bio.html ↩

- Mott, Frank Luther. “A Brief History of “Graham’s Magazine.” Studies in Philology 25, no. 3 (1928): 362-74. www.jstor.org/stable/4172007. ↩

- Mabbott, Thomas Ollive. The Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe–Vol. I: Poems. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 1969. ↩

- Tschachler, Heinz. The Monetary Imagination of Edgar Allan Poe: Banking, Currency, and Politics in the Writings. Jefferson, North Carolina and London: McFarland & Company, Inc, 2013. ↩

- Baldwin, Matthew. “H. P. Lovecraft, Author, Is Dead.” The Morning News, LLC. 15 March 2012. https://themorningnews.org/article/h.p.-lovecraft-author-is-dead ↩

- Stefansky, Emma. “A monstrous primer on the works of H.P. Lovecraft.” Polygon. 23 August 2018. https://www.polygon.com/2018/8/23/17762378/hp-lovecraft-books-cthulhu-necronomicon-stories ↩

- Lovecraft, H.P. “to Fritz Leiber, 9 November 1936.” published on “H. P. Lovecraft’s Favorite Authors.” Donovan K. Louis (1998-2019). http://www.hplovecraft.com/life/interest/authors.aspx ↩

- Cisco, Michael. “Cosmic Horror and the Supernatural in Poe and Lovecraft.” Lovecraftian Poe: Essays on Influence, Reception, Interpretation, and Transformation. Edited by Sean Moreland. 69-88. London: Rowman and Littlefield, 2017. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Great connections!

There’s a world of interest in just one body of work. Thanks for your kind words!

The light that burns twice as bright burns half as long. A strange, fascinating man and an excellent article. Very well researched and a damn good read.

Thanks so very much. I’m flattered you enjoyed it! The research was extensive, so that’s wonderful.

For my money, there’s no scarier story than “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Maybe there are better ones. But none scarier.

Though, I’m willing to be proven wrong.

Let me start by recommending Whistle And I’ll Come To You by MR James… This one has the added advantage of being gloriously odd.

I think it’s a little the opposite, it’s one of the best stories ever written (although how would I know since I have not read 99.999999% of all stories). It is not so much scary to me as poetically intensified psychology of dread, anguish, mental disintegration, drug use, languishing illness, neurasthenia, terror, in a poetically intensified ambiance of oppressive mouldering, stultifying, decay. Of course in our own time the telly, the news, fiction, and movies have made all of the foregoing rather common. Those words “poetically intensified” are important to understanding Poe. He was a highly wrought author baroque perhaps to the point of the churrigueresque, but he did it with such absolute mastery, and beauty as to make it awesome.

You can of course just pick it up and read it as historical Gothic. But, with no disprect, it is not like Lovecraft or Stephen King or other masters of the macabre, and I mean masters, Poe is in a unique and often demanding, literary class of his own.

BTW I believe his true immortality is in his prose fiction, but his poetry is powerful however sparse. Personally I don’t think it is one bit overwrought, however highly wrought, although maybe somewhat tortured. I have no problem with tortured. It would be very overwrought if weren’t so good. But it is so good and therefore is not overwrought

Scarier story? The Confession of Charles Linkworth by E.F. (Fred) Benson of Mapp and Lucia fame

Frightens the bejesus out of me every time I read it.

I thought the fate of Fortunato in The Cask of Amontillado by Poe was creepier though.

Thank you for covering my favorite writer. I’m curious — what do you think about his poetry? From what I’ve read (which admittedly is not a lot), I sense that critics think Poe was a better fiction writer than a poet, and I tend to agree. Some of his poems are great, but others just seem tortured and overwrought (even by his standards). On the other hand, Annabelle Lee is beautiful, I think.

An anagram of Lenore and Raven is “Novel Earner”. Clearly a Poevian in-joke as The Raven is, of course, a poem and would have recouped him very little income. One can’t neglect Poe as a satirist. I’m surprised that nobody has yet remarked how funny he is.

You make an excellent point! If since lost account of it, but one author wrote in forwarding a Poe anthology that most of his work has potential for comic satire. He argued how even the works regarded as peak horror (The Tell-Tale Heart) can be read as effective trolling of the high-brows or his day. Another case of how Poe’s choice of words and omissions allow a world of interpretive interest.

Poe’s poetry has a distinctive stylistic genome compared to his tales. That’s partly why I focus on his short stories—his poems were made with a different intent and style. That being said, I can take different poems over others. Poe wrote poetry like most people change socks: some almost seem written in “stream of consciousness.” If you want a textbook case of overlong and too opaque, read “Al Aaraaf,” which even Poe himself dismissed as amateurish later in his life.

He wrote an earlier poem called Lenore, along the lines of Annabel Lee. Some say however that Ligeia was called that because it rhymes with idea. The name first appears in the long poem Al Aaraaf.

Really enjoyed this feature. I love analyses and contemptuous writers.

I stormed into Poe’s writings as a teen- and when I finally fought my way through to the other side, I was a shadow of my former self.

Poe was one of the best English language poets, and was a huge influence on Baudelaire and Mallarmé among others. I don’t know whether Dostoevsky had ever read Poe, but if he had, Notes from Underground and Crime and Punishment were certainly influenced by him.

Poe fundamentally shaped the way we understand both horror and romance (particularly horror). For Poe, the two concepts were never separate, but interconnected: He lost four young women throughout his life and this shaped him, his understanding of love, and his writing.

when I came to my English teacher about doing my essay on Poe, and dedicating my whole semester to reading his work she was ecstatic, and I now understand why. after I did an in depth breakdown of the Raven I wanted to read more of his work. the narration of Artur pym( forgive me I forget the spelling) was one of my favorites and I was enthralled with all of his elaborate and deep views of everything. he is by far my favorite author and poet and this article captured his style amazingly.

A. E. Poe was a literary artist who painted beautiful landscapes with his words.

But what does this mean?

My absolute favorite quote is from his poem “Alone”

“From childhood’s hour I have not been

As others were—I have not seen

As others saw—I could not bring

My passions from a common spring

From the same source I have not taken

My sorrow—I could not awaken

My heart to joy at the same tone

And all I lov’d—I lov’d alone”

After reading The Cask of Amontillado back in high school, I was instantly captured by Poe’s writing. “Nemo me impune lacessit” and the narrator’s lack of regret- I have never encountered those themes before. Then I had this book which contains his famous short stories which I found hard to devour since I was still young, yet there’s something about the quality of his work that just pulls you in. Of course, if you ask me who my favorite writer is, it’s Poe. Always.

What is some of the scariest stories you’ve read while growing up? Poe or non-Poe.

The first scary stories I ever read came out of a battered book that I stumbled upon, whose name I cannot recollect- and a quick Internet search tells me it was the Third Fontana Book of Great Horror Stories. It chilled me quite a bit back then- an elderly woman being held hostage by her plants, old clothes in a trunk in the attic, an ominous school building were excellent elements to give a fillip to my hyperactive young imagination.

My father being an accomplice despite my mother’s vehement protests, I was plied with anthologies of horror stories which I devoured greedily. I relished Edgar Allan Poe, WW Jacobs, Saki and MR James and was introduced to a number of new writers in Ruskin Bond’s ever-dependable selections of ghost stories. Particularly interesting were the ones set in the times of the Raj, in lonely dak bungalows or Himalayan hill stations, featuring hunting expeditions, secret trysts and dalliances, and ghosts from Indian hinterlands. Ruskin Bond himself has written a number of chilling stories, subtle yet mind-numblingly scary (especially as seen through the eyes of the young schoolgirl that I was then). I remember going around narrating The Fall of the House of Usher and The Monkey’s Paw to a group of wide-eyed schoolgirls.

These were stories written without the tantalising thrills of blood and gore- they were build entirely upon the creation of the atmosphere- howling winds, rolling moors and empty mansions. They ensured that I never looked at a shadow or a silhouette without a sudden misgiving, having to look over my shoulder and hear imaginary noises.

It is only recently that I have been able to lay my hands on a copy of Dracula (and I blush because it’s taken me so long to get to it), and the black, red and white cover beckons invitingly even as the clouds gather outside. The stormier, the better.

The Ladybird books of Nursery Rhymes had an effect on me. The illustrations have a strangely intense feel and an exagerated vertical perspective, resulting in a the sort of clarity of a dream that’s starting to go bad. I still look at these illustrations and both admire them and wonder why they were drawn like this.

Also my parents had a book of Goya’s Caprichos which my sister and I used to look at a lot – very scary, creepy stuff, but a world familiar from our own nightmares. Or maybe our nightmares were formed these prints?

Robert Swindells – Brother in the Land

Genuinely terrified my as a youngun. Bleak but with glimpses of hope consistently built up and dashed. Couldn’t even look at it for a few years after I first read it (age 7 or 8 I think).

There was a terrifying story in one of Andrew Lang’s fairy story collections – I think it was the Orange Fairy Book – concerning a group of standing stones that go down to the river to drink on one night in the year (standard folklore element), and a wicked wizard who tries to steal the treasure that lies under one of the stones while they’re away, and gets ‘crushed into powder’ when the stone comes back. Between that and ‘Marianne Dreams’, I have never really been able to look a standing stone in the face again, which in my profession is a bit of a handicap.

I don’t remember the name of it, but when I was a child I owned a book of gruesome poems with an illustration across the middle pages that used to terrify me. It was a slim volume, but the entire centre spread was taken up with a colour drawing of a green-faced egyptian queen, giant, stomping through a suburban street and setting fire to her surroundings. Never left me…

Having to read Poe at university, I had crawled through the stories, amused by the thought that he ate thesauruses for breakfast but unmoved by the stories, till I read The Black Cat, which really hit home.

The descent of the lead character into dissolution and mania is less arch and gothic than other tales; then the scene in the cellar, where he glories in his cleverness, and then the moan of the cat which Poe has expertly hidden from the reader as well as the character, puncturing his supposed cleverness, all made me feel a visceral horror. I felt the infinite possibilities the universe holds for denying the clever plans of the intelligence of man, just for a moment before I refocused on the book. I guess that’s what others get from his writing.

I can’t stand the Raven, though. I think it was written backwards, to demonstrate that the act of writing poetry follows rules more than inspiration, which is a wonderful point to make, but the poem is so much a rote that it might as well have been written by a machine. Which was his point, and very of the prescient moment, but it’s just clunky romanticism to me. And I’m not very keen on most romantic poetry anyway.

I’m finding Poe is slowly growing on me. It’s like poetry in that you can’t try to read it all in one go; it can’t be rushed.

Really great article. Some might like to try listening to Poe. YouTube has a huge selection of his poems and stories read by almost as many luminaries.

I would recommend:

* ULALUME by Jeff Buckley.

* RAVEN by Christopher Lee or by Vincent Price but there is also John

* DeLancie, Basil Rathbone, Christopher Walken, James Earl Jones

* ANNABEL LEE by Basil Rathbone (his Raven is great too).

Actually there are far, far too many to recommend. But you can find many of his poems and tales beautifully read. But I would also recommend VINCENT, Tim Burton’s hommage to Poe and Vincent Price (it’s narrated by the latter).

Just listened to James Mason read the Tell-Tale Heart (he also does the Raven and he also narrates a fine 1953 animation of the T-TH by UPA) and maybe because Poe’s tales are so very prose poetic it helps to hear them read by a good reader. You get a fuller range of poetry’s acoustic advantages in terms of rhythm and intonation. I believe Vincent Price does a nice Cask of Amontillado and Gabriel Byrne does a great job on Masque of the Red Death.

Personally I would suggest readings over dramatizations.

I suppose I just accept the stories for what they are, with their own unique atmosphere – which I don’t judge by modern standards.

Over the top, repetitive, silly…yes, definitely, but I still find they have something in their evocation of disturbed psychological states. It would be different if it was a long novel, but I find them easy to read being so short.

I agree, they are by no means perfect, but I have also really enjoyed them. I also enjoyed his writing in some parts. For example, I enjoyed the ramblings of the insane narrator in the Tell-Tale Heart and the repetitive words and phrases that brought this insane voice to life.

But more than anything I wonder if the great thing about Poe was his ideas, and I suspect he may have written stories based on ideas and topics no-one else had at the time. However, I am not knowledgeable enough about historic literature to know if this is true.

Would anyone else be able to confirm? Would writing about killer orangutans, detectives, ghost ships, whirlpools and Insanity have been considered new at the time? Had anyone else done it before him?

From my limited knowledge plenty of it was new. (For instance the procedural detective.) But books like The Monk, A Sicilian Romance and etc had been around for a while when Poe was writing, so the gothic elements were more well trodden.

But hopefully someone who knows more than me will crop up. Perhaps something on Poe in context may even make a good post. What were his contemporaries writing in the US? How was he reviewed?

We need to try reading Poe without the expectations aroused by a series of melodramatic ‘Hammer Films’

He was a poet, capable of conjuring up an atmosphere all his own.

Do not expect ‘Hollywood’ horror. He builds his narratives, slowly. It is intentional.

He influenced (and was highly rated by) Baudelaire, Mallarme and Lovecraft.

I think Poe is one of those writers (like many writers beloved by cinema) whose ideas are greater than his prose. And each one of his stories has a cracking, if rather morbid, idea.

And the prose itself, a bit like Lovecraft’s is I think it’s worth remembering that Poe’s writing in the pulp Gothic “penny dreadful” or “shilling shocker” tradition. It’s his later influence, the fact that he was discovered and translated by Baudelaire, inspired artists, and later film directors, that have raised his work from schlock to (disputed) classic. His prose itself is at best workmanlike- it’s good at one thing – evoking an atmosphere of sepulchral gloom. The repetition helps with that.

After all- who reads “Dracula” for Stoker’s prose style?

You know, rereading some of Poe’s stories in the last couple of days, the style is growing me, and in many places reminds me of Mervyn Peake- the same deliciously oppressive sense of wading through ponderous prose as if through a swamp, every sentence requiring a bit of extra effort to parse. That’s not in itself a bad thing- Henry James, no fan of Poe, had a similarly dense style, and it does give a story of say ten pages a feeling of weight and substance. I’d like to hear these read by Christopher Lee. Maybe Sir Christopher should have a break from recording heavy metal and lend his unique VOICE OF DOOM to recording Poe. But far be it from me to tell a 91-year old man what to do.

Edgar Allan Poe is arguably one of the greatest writers of all time. Not only was he a master of writing about the macabre, but he was also the man who created detective fiction. If it weren’t for his very own sleuth C. Auguste Dupin, we would never see characters like Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot. His influence was even felt outside of the west. In Japan, famed mystery writer Taro Hirai based his own pen name “Edogawa Ranpo” on the prolific poet. There’s so much I have to say about this man since he’s been a great inspiration to me as a writer.

Edgar Allen Poe is one of my very favorite writers – spent many a dark night, in bed, w/only one light on, everyone else in the house asleep, scaring MYSELF reading his stories… what a writer!

The Artifice published great content on Poe and Lovecraft.

I love Edgar Allan Poe and one of my favorites from his works was The Cask of Amontillado, which was his first story that I have read in 6th grade. It gave such an impact on me as a kid, I don’t know why, and it has never left ever. Since then I started reading his works. I’m so happy he’s featured here on The Artifice.

I am struggling to maintain momentum with the Poe. I’ve conquered ‘the Murders in the Rue Morgue’ and the ‘Fall of the House of Usher’; both were dull. The unravelling of the Rue Morgue murders by Dupin felt so contrived, a paint-by-numbers deconstruction of the ‘impossible murder’. Dupin himself, coldly unlikeable; his character essentially a device of analytic ‘deduction’, with none of the human flaws of say, Holmes. The solution to the murder itself was bafflingly banal.

‘The House of Usher’ was more frustrating still, since the narrator insisted on telling us what happened with Usher, rather than showing us the dialogues, the increasing psychic breakdown and horror. For instance:

“In the manner of my friend I was at once struck with an incoherence – an inconsistency; and I soon found this to arise from a series of feeble and futile struggles to overcome an habitual trepidancy – an excessive nervous agitation”.

There is no space for the reader to work out or guess at Usher’s mental state. Rather, the narrator just tells us, and the effect – to my mind – leaves us cold. In a story so heavy with horror, Gothic buildings, and the cracking of the human mind under intolerable and inexplicable pressure, there is very little suspense, and very little left to the imagination of the reader. Poe’s imagination may have been hallucinatory, but its externalisation in these stories is rather flat.

Your aren’t off-mark on the mystery element of Poe’s Dupin tales. They fall more into a separate category from his horror tales—his detective works (the first in the English language) are more dedicated to confounding his audience’s deductive skills than evoking fear. Dupin is the first in a line of genius detectives, but, being the first, he is also among the more coarse in effect for modern eyes. Disdain isn’t unbelievable. In fact, Poe’s second Dupin work was not well-received in his day and isn’t well known today for that reason, I believe.

Just finished reading The Masque of the Red Death and The Pit and the Pendulum.

Not feeling sleepy at all, not one little bit.

I read Poe as a child, I was not particularly frightened by written stories. Books were my escape from a much more scary reality. When I grew up,all that changed: I started to understand what real horror fiction was. For years, I was terrified of empty buildings after reading King, for instance.

Today, my nerves are made of hardened steel; no fiction can frighten me again. Reality is too scary.

That said, a discreet censorship of your children’s access to horror fiction is advisable: they will inevitably find their own horrors anyway where you least expect it.

Great piece. The first terrifying story I read was The Hound by H.P. Lovecraft. Once I finished reading I read it again just to experience the sensation again and again until I got addicted to Lovecraft tales. Then I was certain that horror was made for me and I still believe that is the Art topic that moves me the most.

When I discovered the connections between Poe and Lovecraft I got mad about horror intertextuality and started exploring all possible existing relations between their works.

I think my favorite short stories by him are The Cask of Amontillado and The Fall of the House of Usher. Both brilliant. And I also love his poem “To Ulalume. A Ballad”.

I continue to read Poe, having discovered him as a child, because he’s bloody wonderful!

If you’d care to read something terrifying for adults, may I recommend Cormac McCarthy’s Outer Dark? Genuinely unsettling, creepy and terrifying. Beautifully written, to boot. McCarthy’s Child of God is another in the same vein. Both highly recommended.

I had a huge addiction to Poe as a child. I spent some of an end-of-school prize book-token (swot) on a hard-bound “Tales of Mystery and the Imagination” with wonderfully grisly illustrations by Arthur Rackham. I also read a lot of HP Lovecraft, most of which was probably more odd than genuinely chilling. But it’s probably MR James who sticks with me most: the way he could conjure up the idea of something strange, lurking at the very edge of one’s sight. Strangely, I never found Roald Dahl at all scary, probably because of the way his somehow joyous relish of the grisly jumped off the page.

It feels sad to realise that his personal life was as haunted as his stories. But on the other hand, I feel happy that instead of breaking down or getting depressed, Edgar turned his adversities into a source of inspiration. To me, you are a true hero Edgar.

If you really put the wind up yourself, read Poe’s “tales” in a big old house, alone by the light of a single lamp with an open door behind you.

I find Poe florid rather than hard to stomach.

But I do like Ligeia and Masque Of The Red Death.

I wasn’t particularly scared by his books I read – disturbed at times, upset, tearful (lots of books made me cry my eyes out, which I loved), but scared? Not so much.

I love all of his works. But my most favorite of all is the compilation book of his horror stories which featured The Human Chair. That horror anthology gave me another perspective when it comes to the “horror” genre. He’s truly a brilliant writer.

Perhaps it would be interesting to discuss the fascination of the French with Poe, who idolise him. It started with Baudelaire’s translations of course, but continued through Mallarmé and, as anyone familiar with French society will attest, continues to this day, through all levels of it.