From Homer to Fante: Blindness and Literary Vision

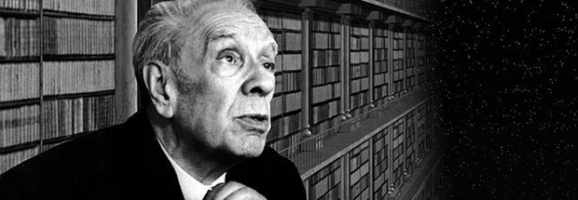

Introduction: Jorge Luis Borges as a Case Study

There are countless writers who are considered innovative, but there are precious few who actually deserve this bold labeling. Cormac McCarthy might be one of the most distinctive writers of our time, but where would he be without William Faulkner’s impressionistic, Southern-fried prose? Franz Kafka is so engrained in popular culture that the term “Kafkaesque” is casually used in conversation, but it is clear that Nikolai Gogol was on Kafka’s reading list during his impressionable teen years. If one writer from the past century can be considered truly singular, it is the Argentine short story master Jorge Luis Borges. He never wrote a novel, which perhaps is the culprit behind his lack of mainstream recognition. This lack of a published novel is far from a gaping void, as his short stories, essays, and plays constitute the richest and most self-referential novel ever published.

What is perhaps most remarkable about Borges’ output is that every single word was written when his vision was severely ailing, and many of these words were written when he was completely blind. Rather than limiting his ability to create literature, Borges instead seemed to view his lack of sight as liberating. His literature is constructed in a labyrinthine structure like that of no other writer. Paradoxically, Borges’ prose is among the most cinematic and visual in the Western canon. Blindness and literary greatness may appear to be incompatible, but Jorge Luis Borges is far from an isolated case. From ancient Greece to the contemporary United States, writers who could barely see the words they were typing have created transcendent literature. These instances indicate that perhaps sight is restrictive and constricting, and that it must be removed in order for true vision to emerge.

Homer: The Founder of the Western Canon’s Vision Exceeded His Sight.

In order to begin this survey of blind writers, one would have to time travel from 20th Century Argentina to Ancient Greece. For centuries, the Roman Virgil, with his clearly Greek-derived epic The Aeneid, was regarded as the master epic poet. After all, it is Virgil, not Homer, who leads Dante on his tour of the Inferno, and it is the Romanized Ulysses, not Odysseus, which graces the title of James Joyce’s masterpiece. Yet, during the past century, Homer’s preeminence has been re-discovered, and it is The Iliad and The Odyssey which now dominate high school and university curriculums. There are historians who insist that it is unlikely that Homer actually wrote these epics, while others argue that he even may be a mythical character. Similarly, it must be remembered that these stories were passed down through oral tradition, rather than simply being secreted in Homer’s imagination.

Allowing these factors, and assuming that Homer did indeed write these twin epics, it is safe to say that these two works overflow with imagination, humanity, intense imagery, and above all, vision. The trojan horse, the song of the sirens, and Odysseus’ battle with the Cyclops, to name just three images from Homer’s work, are deeply entrenched in the collective consciousness. These images may appear so archetypal now that it is easy to believe that they always existed. Yet, someone had to put these intricate, grandiose narratives to words. It is difficult to imagine another writer improving on Homer’s handling of these complex works, let alone another blind writer. Like other aspects of Homer’s muddled biography, his blindness continues to be debated by historians. The overwhelmingly vivid imagery and plotting seem to indicate that only a writer with complete sight could construct such extensive works of poetry. Yet, conversely, perhaps this lack of sight is what lent Homer’s poetry its intensely visual aura. This certainly appears to be the case with the next writer in our chronological journey. Luckily, there is no debate that the following poet was blind, and the fact that he existed is without an iota of doubt.

John Milton: Paradise Found, with a Little Help from His Daughters.

The case of John Milton, whose Paradise Lost is widely considered the most accomplished epic poem in the English language, is slightly different from the other writers mentioned in this piece. After all, it is well documented that his work was transcribed with the help of his devoted daughters. (This is ironic, considering that, then and now, Paradise Lost has been condemned as virulently misogynistic.) Akin to countless writers throughout history, Milton struggled for years in poverty and obscurity before suddenly rocketing into literary fame. Before he began Paradise Lost in 1658, Milton had merely a single, modest collection of poems to his name. Also before the composition of his most renowned work, he maintained full use of his sight. As he reached his 50s, his sight quickly began to vanish, while his vision simultaneously erupted in full bloom.

While it is unclear how large a percentage of Milton’s involvement was compromised by the transcribing of his daughters, it is remarkable that his most fully realized creation did not occur until he lost his ability to see. Before losing his sight, Milton’s poetry was pleasant, charming, and surprisingly workmanlike. Paradise Lost, however, is a sprawling, maddening, and undeniably brilliant epic poem. Like the work of the other writers discussed in this piece, it is truly a singular literary achievement. The premise- an updating of the Adam and Eve myth, complete with contemporary political parallels and genre revisionism- seems stale and derivative. The execution, however, is truly inspired. The characterizations and plot points are so vivid and visceral, one could reach out and touch them.

This illusion of tangibility appears to be a direct result of Milton’s blindness. Milton’s poetry written while his sight was intact seemed restrained and stifled. Apparently what was restricting him was the very ability to see. Akin to Homer and Borges, the lack of sight produced a profound and ingenious sense of vision in the mind of John Milton, and the result was one of the most immortal pieces of literature ever written. If Milton had died before Paradise Lost was published, it is unlikely that he would be remembered today. Yet, by unleashing the full powers of his craft despite his lack of sight, Milton finally discovered the extent of his vision.

John Fante: Palm Trees, Mountains, and Oceans Viewed Through a Blurred Lens.

In comparison to the aforementioned Borges, Homer, and Milton, the Colorado-born writer John Fante is hopelessly obscure. Fante never won a major literary prize, and his work is unlikely to be taught at most high schools and universities. Although two film adaptations were produced of his novels, both were piddling misfires that did nothing to boost his audience. However, his literary output, as relatively scant as it is, is ultimately as distinctive as the work of the previously noted scribes. Fante’s magnum opus, Ask The Dust, an intensely personal account of a struggling writer in 1930s Los Angeles, was written nearly two decades before Fante’s sight began to fade.

Yet, if one compares this work to his final novels, constructed when Fante had lost 100% of his eyesight, the stylistic similarities are striking. His penultimate works, The Brotherhood of The Grape and Dreams From Bunker Hill, unsurprisingly recycle the thematic concerns and West Coast working-class setting of Ask The Dust. Fascinatingly, however, the distinctive prose style Fante exhibited in his most iconic work is fully intact. In many ways, Fante is as singular as Borges or Milton. His prose is as intensely descriptive as Henry James or Thomas Wolfe, yet as lean and economical as Hemingway and Raymond Carver. It is no surprise that Fante was a cited influence on writers as diverse as Charles Bukowski, Carey McWilliams, and Academy Award-winning screenwriter Robert Towne.

Perhaps the most distinctive aspect of Fante’s literature is its strangely off-kilter perspective. If one were to read Ask The Dust without realizing that Fante lost his eyesight years after the novel’s publication, it is natural to assume that the writer was already blind. The imagery, full of placid oceans, far-off mountaintops, bustling urban markets, and the luminous sight of a Mexican waitress’ legs at a grungy diner, are vivid yet oddly hallucinatory. At times, the novel seems written by somebody with a vague idea of what the world looks like, rather than an individual who has seen life first-hand and up-close. The skewed perspective evident throughout the novel re-appears in his final works, and by this point it is all too clear that Fante’s sight has faded. This tilted view of life reflects the disquieting, subtle surrealism inherent in even the most banal daily minutia, and speaks to the universality of Fante’s novels.

The fact that these four writers were able to produce indelible works of literature while afflicted with blindness is not merely a tear-jerking inspiration. Nor is it a strange enigma or baffling paradox. Instead, it is an affirmation that every loss is offset by a surprising gain. A lack of physical sight greatly enhanced the vision and unique precision in which Borges, Homer, Milton, and Fante constructed their idiosyncratic works of literature. Only a single writer could have written Ficciones, The Iliad, Paradise Lost, or The Brotherhood of the Grape. That these four works were written through the ardors of blindness is a testament to the clarity and singularity of vision produced by losing one’s sight.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

This article is awesome, and a very fascinating topic to discuss. Well done!

This was a very useful read for me. I am visually impaired (blind in one eye and limited vision in the other) I was diagnosed with my condition (JIA & Uveitis) at age 2.

Touch the Top of the World by Erik Weihenmayer is a good one; he lost his sight gradually in childhood, becoming completely blind in his early teens, and he has some good details regarding how he navigates through life now.

What a great piece.

Not that I have anything particular to offer to this article, but I used to work in an in-home care for a woman who was born blind, and as an inveterate “reader” of books on tape, she used to discuss the visual imagery in the books with me.

One of the hardest concepts for her was “glitter”. I finally gave her a tactile metaphor of a showerhead or sprinkler with cool jets of water that kept changing its timing and angle of the water jets….which may or may not have helped, she said she’d think about it.

It was very interesting to talk over things that she perceived totally differently because of the complete lack of visual referents: for instance, to her, long braided hair was the “prettiest” because it appealed to her in a tactile way. Curly hair was much less “attractive”, as it felt “tangled” to her.

I like Helen Keller’s work. She was both blind and deaf from the age of 19 months and the the author of several books and many articles.

I thought of Helen Keller right after I read this too.

John Milton was completely blind when he wrote Paradise Lost although he only began losing his sight in his 30s

I had no idea about John Milton. I read Paradise Lost for a college English class years ago, but I’m sure I didn’t appreciate it properly then.

A unique and intriguing article. I like that you argue that blindness places no limit on one’s literary vision.

I found this article very educational for me, thanks.

John Hull – Touching the Rock: An Experience of Blindness

Zoltan Torey – Out of Darkness

Sabriye Tenberken – My Path Leads to Tibet

Jacques Lusseyran – And There Was Light

Bryan Magee and Martin Milligan – On Blindness

I’ve read the Hull and the Lusseyran (writing a novel with a blind protagonist, as research), and would highly recommend both of them – the Lusseyran memoir in particular is absolutely fascinating in its own right.

Lovely read. I have read multiple work by blind authors and books with blind characters. ‘You Need To Go Upstairs’ by Rumer Godden is a famous short story written in second-person and the “you” is a blind character.

Taking Hold by Sally Hobart Alexander is about how the author went blind. There’s also Follow My Leader by James B. Garfield which is a fiction book.

I read a memoir written by a deaf writer: Deafness by David Wright. That’s well worth the read if you can find it. I picked my copy up from an Oxfam shop.

Ryan Knighton has written two memoirs: Cockeyed, about losing his sight over fifteen years in early adulthood, and C’mon, Papa, about his experiences as a blind new father.

Ha, I just read Oliver Sacks’ The Mind’s Eye, which contains a chapter that is pretty much nothing but a listing of books by blind authors.

This was a really compelling read, thanks for sharing!

Books with good blind characters are BlindSided by Priscilla Cummings, A Girl’s Best Friend by Harriet May Savitz, The Window by Jeanette Ingold, and Girl Stolen by April Henry.

I’m blind, so this is a topic I know well :). My favorite blind fiction authors are Deborah Kent Stein and Beverly Buttler. Deborah Kent Stein wrote Belonging, One Step at a Time, and Heart Waves. Beverly wrote Light a Single Candle and its sequel A Gift of Gold.

Great read.

An insightful article. With Milton, poetic meaning comes to rely more heavily on sound after his blindness than before. I suppose we would all read more carefully if we used our ears more than our eyes–listening to the language and seeing the world through other senses. Makes me wonder, too, about authors who have lost other senses: do we privilege blindness over deafness in a writer? why?

Never thought to consider how prose changes once the writer has lost their sight. I had no idea of the incredible difference between their writing abilities because of the significance of their own vision. A very cool article, and written well. I really liked the chronological organization of the authors.

It’s intriguing to me that “Ulysses” is only mentioned briefly as the title of “James Joyce’s masterpiece” in an essay about writing and blindness. Joyce was a blind writer. Struggles with ill health and poor eyesight greatly impacted his later work. From a scholarly point of view, ULYSSES is also not Joyce’s masterpiece, FINNEGANS WAKE is. One of the many reasons for this (other than the fact that ULYSSES incorporates too much), is the very aural nature of the text. Joyce dictated sections of the text to Beckett. There are clips of him reading Anna Livia on Youtube. He was, what we would term today as, legally blind by the time the latter novel came out. This is worthy of a paragraph in this piece here – at least.

C.f., Teiresias in Œdipus Rex and Antigone.