Historical Fiction: Understanding the Past Through Gould’s Book of Fish and Wanting

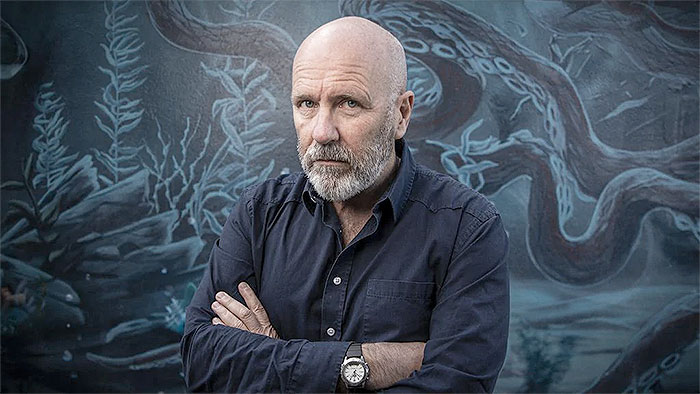

The analysis of history is not without its problems. This essay seeks to illustrate how historical fiction, as a form of historical discourse, can contribute to our understanding of history by approaching it from a perspective not available to that of traditional historical records. It will show, using a brief exegesis of Richard Flanagan’s 2001 novel Gould’s Book of Fish and his 2008 novel, Wanting, how literary narrative has the capacity to communicate an accessible understanding of the past from the perspective of voices often omitted from formal accounts. Flanagan, a Rhodes Scholar historian turned novelist, offers an insightful perspective on these themes. His work, as will be shown below, highlights the limitations of conventional historical records and seeks to convey the individual stories of the past so often excluded from formal accounts of history.

“I am drawn to questions that history cannot answer.”

Richard Flanagan 1

Representing History

Narrative can be understood simply as a series of events represented in language. The need to distil our multifaceted and incredibly overwhelming experience of reality into something cohesive should not be understated. But such a process is not always easy; such a process, in fact, is not always possible. In few fields is this discrepancy so distinct as in the study of history. How we understand the past is fundamental to our identity, to the way in which we perceive our world. Yet it is also inherently problematic: how are we to represent that which no longer exists? This very question is a long-standing point of contention in historical studies.

This presents an obvious problem for any one who seeks to tell a story of the past: how does one choose what to include and what to omit. This is a central preoccupation for historical works and the choices that are made by historians and artists are often heavily weighted by political persuasions and motives. Problematic accounts of history were, and still often are, excluded to make way for narratives that contribute to truths reflecting the desires and intentions of the creator. This makes perfect sense: accounts of the past inevitably serve a purpose and it would be impossible to represent an all-encompassing account of history without exclusion.

The problem is, that which is excluded is very often the perspectives that lie outside of established hegemonic structures of power: feminine perspectives in the context of patriarchy; colonised perspectives in colonial worlds; etc. So whilst the methodologies of historical accounts vary based on the intentions of the author, omission is inevitably a mainstay. This adds another element to the common truism that history is always written by the victor. As Bill Ashcroft perceptively notes, it is “less widely recognised that in any historical account History is the winner.” 2

Historical Fiction

The field of literature does not escape these complications, and they are perhaps most pronounced in the genre of historical fiction. Historical fiction is itself a problematic term with varying accounts of what attributes characterise it as a genre. For the purpose of this essay, historical fiction can be conceptualised simply as any literary narrative that seeks to tell a story of the past. It is important to acknowledge, therefore, that historical fiction inevitably exists upon a spectrum between validated facts and authorial speculation (creative license, if you like). Historical fiction acknowledges that an unequivocal account of the past is, by its very nature, not possible. As Harry E. Shaw notes, “there are limits to how much you can include of the full spectrum of life in history.” 3 Any account of the past must necessarily concede that it is not a full account; even a direct, first-person recount of an historical event is limited to the single perspective that experiences it.

Alternate Accounts of the Past

The degree to which an author’s interpretation of history interacts with true, historical events varies. It is this dynamic interaction with the past that differentiates it from other forms of history. As author-historian Richard Slotkin writes, there is a point at which “the historian must choose between knowledge and understanding: between telling the whole story as she or he has come to understand it; or only what can be proved, with evidence and argument.” 4 It is this very subjectivity that lends historical fiction its value as a form of historical discourse. Historical fiction has the capacity to present alternate accounts of the past, to deviate from official accounts of history to highlight the individual, overlooked or even omitted stories that together generate a more comprehensive, holistic account of the past. Historical fiction liberates, what Hayden White terms “the rest of the real.” 5

To presume that any retelling of the past is a complete and unequivocal account is an impossibility that historical fiction refuses. Instead, it seeks to fill in the gaps of history to offer a further consideration of the past that is often imperative to a holistic understanding of the conditions that have led to our current circumstances. Fiction can contradict, complicate and confuse and, sometimes, to convey the realities of the past these experiences are entirely necessary.

Gould’s Book of Fish

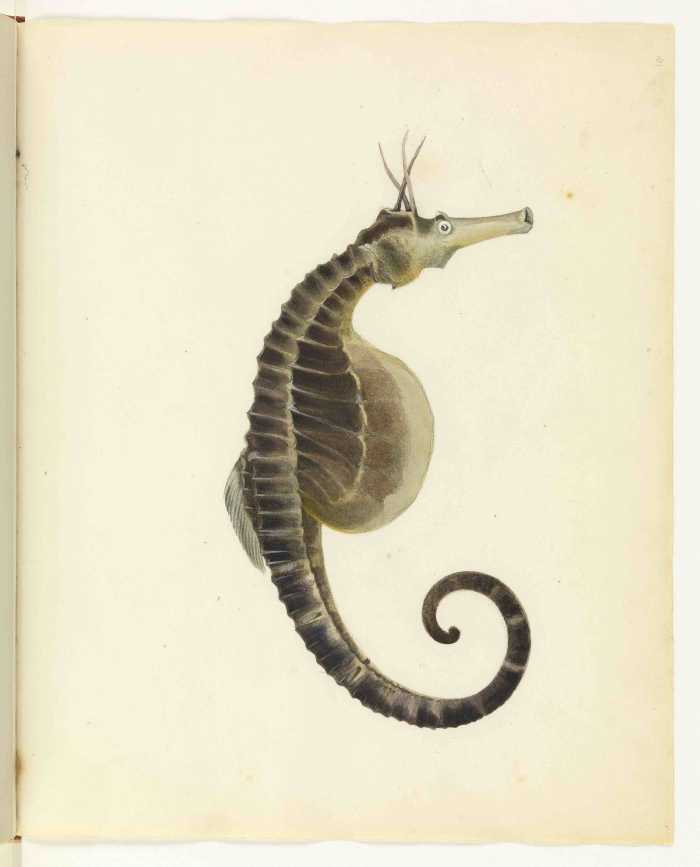

In 2001, Tasmanian author Richard Flanagan published Gould’s Book of Fish, 6 an historical novel that moves across periods of Tasmania’s past from a contemporary setting, to early nineteenth-century Van Diemen’s Land. The novel looks back to a period known as the Black War: a dark and often overlooked period in Australia’s past, a desperate attempt by the British administration to remove the island’s indigenous population that saw a discordant army of petty felons face a fractured guerrilla movement of Indigenous Tasmanians. Official histories of the Black War are wanting, the colonial administration obviously unenthusiastic about documenting a conflict that saw a death rate per capita of two and half times that of Australia in World War Two. The novel is based on an historical relic, a sketchbook of fish painted by the convict William Buelow Gould who goes on to be fictionalised as the eponymous narrator of Flanagan’s novel.

The novel is separated into two distinct time periods, a structural choice that allows Flanagan to contrast modern Tasmania with its colonial past. The first section is narrated through the first-person perspective of Syd Hammet, a petty criminal who makes his way by selling fraudulent antiques to American tourists. His narration is severely unstable, Hammet declares that he himself has “come to the conclusion that there is not much in this life that one can be sure about,” and his self-proclaimed apprehension towards objectivity severely destabilises the readers trust in his ability to effectively recount his story.

Syd Hammet’s antiquarian endeavours are what eventually lead him to Gould’s book of fish: the “weird record seemed to be that of a convict called William Buelow Gould who in the supposed interest of science was, in 1828, ordered by the surgeon of the penal colony of Sarah Island to paint all the fish caught there.” Hammet discovers it in the forgotten corner of a dusty antique store and he develops a preoccupation with the book that approaches the neurotic. The book acts a proverbial window into the past, and a catalyst for Flanagan’s broader discussion on the validity of historical accounts. In few places is this doubt more evident than in “the eminent colonial historian Professor Roman de Silva,” a character that Flanagan uses to illustrate the inadequacies of formal historiography. Professor de Silva, as Hammet describes, “looked for truth in facts and not stories,” and he dismisses the relic as a fraudulent recreation that reflects Hammet’s disposition towards forgery.

Undeterred, Hammet continues to explore the history of the book. It accompanies him everywhere until he inconceivably loses it in a pub: “Where I had left Gould’s Book of Fish there now remained nothing—nothing, that is, save a large, brackish puddle being mopped up by the barman with a sponge.” Hammet takes it upon himself to rewrite the book, a powerful symbol that gestures to the significance of producing accounts of the past. From this point in the narrative, a bizarre series of events (beyond the scope of this essay) lead to the narrative point of view shifting in perspective and time to William Buelow Gould, in early nineteenth-century Van Diemen’s land.

From this point, Flanagan’s text more directly interacts with past as it represents an array of historical figures. These characters range from George Augustus Robinson, the colonial ‘protector of Aboriginals,’ to Rear Admiral John Bowen, who led the British invasion of Tasmania in 1803. By using the genre of historical fiction, Flanagan grounds his work in a factual setting. The dates line up, the names (whilst sometimes loosely applied) exist in historical annals and the locations can be visited in Tasmania today. But by fabricating the details of his story and focalizing them through his first-person narrator, Flanagan seeks to illustrate an account omitted from official records. It is at times outrageous, audacious and shocking, portrayals are racist, sexist, misogynist, but what they serve to achieve is a foregrounding of the problems of representations. Such portrayals effectively subvert the reader’s presumed knowledge of what actually happened.

The story Flanagan tells deviates significantly from the history that occupies the popular imagination of Australia’s colonial past. William Buelow Gould, describes how his first contact with Tasmania was “that moment in 1803 when as a boy I first leapt off that whaleboat with Mr Banks’ pistol sticking in my back,” not a heroic gesture of exploration, but “just in case my resolve might falter.” He describes how “Lieutenant Bowen, in his fury, took the subsequent arrival of a few hundred blacks with their families hunting kangaroo as a declaration of war.” The subsequent slaughter of the Indigenous population at the hands of the heavily armed Europeans contradicts the hard-working settler narrative often presented as Australia’s past.

These alternate perspectives also extend a humanistic voice to Indigenous Tasmanians. The character of Tracker Marks who “seemed more white than a white man” offers a critical perspective of Empire, as he asks how “power & ignorance can sleep together.” Flanagan uses these subversions to deconstruct the coloniser-colonised binary and establishes an intersection between white convicts and Indigenous peoples, two groups impacted by the colonisation project. The language of the narrative delves into a constructed argot: dementung, “that bastardised dialect that was part-blackfella, part-whitefelon.” Gould himself is painted in ochre by his Aboriginal lover and describes the experience “as if we shared something that transcended our bodies & our histories & our futures.”

Flanagan explores all aspects of history – even the doubtful ones. He refers to the enigmatic figure of Matt Brady, the notorious bushranger who – so the story goes – rode his stallion valiantly into Hobart and nailed up a wanted poster of the Governor in full view of the town. Gould questions his existence: “Who was this Brady? It occurred to me that he may have been Tracker Marks. Or René Descartes.” Such philosophical musings allow Flanagan to associate an Australian folk legend with the archetype of the European Enlightenment in ways that traditional accounts of history could not. Gould’s reflection culminates in a reflexive assertion that reiterates the significance of his story: “I even wondered if he was in the end just an idea, but then his story would properly belong to in the realm of literature, & not here in a truthful account.” Paradoxically, Gould’s assertion of the factuality of his account destabilises it, and once again, the reader is made aware of the often arbitrary distinction between historical fact and fiction.

Flanagan’s narrative allows him to build an ambient atmosphere that captures the benevolence of nineteenth-century Tasmania. He describes the systematic suffering of his narrator, who tells his story while gaoled in a sandstone cell as it slowly fills with seawater leaving a “foot of air space at the top of the cell at high tide”. Gould describes Sarah Island, the most notorious penal settlement in the Empire as a place where “Nature was inverted,” a “stunted island of misconceptions beneath the southern heavens,” with a commandant dressed in “a magnificent new blue uniform, reminiscent of that worn by Marshall Ney at Waterloo” and wearing “a gold mask that perennially smiled.” These poetic descriptions are anchored to reality by their historical references but increase reader engagement to more effectively communicate an underlying theme of Flanagan’s work: history has a profound impact on our present and we must digress from traditional accounts if we are to learn from it.

Of course, the creative license inherent to historical fiction mitigates its ability to accurately depict the past. Gould stages a dramatic escape from his saltwater cell. Sarah Island, transformed into a pseudo-European shrine to the Enlightenment equipped with a steam train (that, symbolically, runs endlessly around a circular track) as well as a palatial Mahjong Hall, is destroyed in a dramatic explosion that is wildly fantastic and far from any accurate historical account. Furthermore, Gould metamorphoses into a seahorse and swims through time to come face to face with Syd Hammet’s business associate, linking the whole story back to the first half of the novel in a mind-bending, cyclical narrative structure. That said, it is precisely this wild account that gives weight to historical fiction as a way of telling history. Because now we are not in the past. The novel arrives so abruptly back in the present that it is impossible to not associate Gould’s reality with our own. Flanagan takes Gould’s story, and drags it directly into the reader’s reality in a way that allows us to consider the significance of such a past and the consequences it has on our present. In other words, Flanagan explicitly shows to the reader not only the inescapability of the past, but also it’s consequentiality. Characteristics that traditional accounts of history behind the screen of retrospect fail to achieve.

Wanting

In 2008, Flanagan went on to publish Wanting 7 another work of historical fiction that aligns in many ways with Gould’s Book of Fish.Wanting concurrently tells two related stories: the attempt in the early 1800s by Governor John Franklin and his wife, Lady Jane Franklin to ‘civilise’ a young Aboriginal girl as well as the story of Charles Dickens, twelve years later as he writes a play defending the honour of John Franklin’s ill-fated Northwest passage expedition. Again, both stories are imbedded in an historically accurate setting that sets the scene for the narrative.

“The war had ended,” the novel begins, “as wars sometimes do, unexpectedly.” As in Gould’s Book of Fish, the Black War is central to Flanagan’s narrative. It opens at Wybaleena, an Aboriginal settlement on Flinders Island, situated between Tasmania and the South coast of the Australian mainland. The island, managed by George Augustus Robinson, was used to imprison Indigenous Tasmanians detained by the British. As the third-person omniscient narrator notes, “Other than that his black brethren kept dying almost daily, it had to be admitted that the settlement was satisfactory in every way.” The novel is narrated in the historical present, as such, the language is often anachronistic with terms like ‘thus’ and ‘thou’ regularly used. The narrative voice describes notable events to contribute to the setting of the scene: “It was 1839. The first photograph of a man was taken […] and Charles Dickens was rising to greater fame with a novel called Oliver Twist.” By addressing such significant international events, the narrator draws the reader away from the immediate setting of Tasmania and situates the narrative within a broader, worldly setting.

John Franklin, newly instated as Governor arrives to Wybaleena with Lady Franklin who is immediately “taken with a small black girl dancing in a children’s corroborree staged in welcome.” Her name is Mathinna and, orphaned by the war, is soon adopted by Lady Franklin who declares that “She will be as our own.” Lady Franklin develops a “rigid programme of improvement,” as she seeks to “civilise” Mathinna into English high society. Predictably, Mathinna resists, preferring the freedom of the outdoors “and the feel of the earth beneath her bare feet.” But Lady Franklin persists with her pseudoscientific endeavour with Mathinna becoming “my experiment” as Lady Franklin describes her.

The civilised standards of dress and deportment that Lady Franklin sees fit for a young lady oppose Mathinna’s natural desires. Mathinna seeks a life outdoors, embracing the natural environment. She longs for the “sensation of the soft threads of fine grass feathering beads of water onto her calves.” Lady Franklin attempts to suppress such desires and in doing so develops an important distinction that the novel makes between the civilised and the savage as being simply, the ability to inhibit such natural desires. The European characters of the novel distinguish themselves through their attempt to constrain their natural desires and passions – their Wanting – and determine this to be the characteristic of civilised society.

The text conveys this distinction through obvious symbolism, such as Mathinna’s opposition to wearing shoes: “She will be shod and she will be civilised,” Lady Franklin insists. Interestingly, Mathinna is not the only one who struggles with these conditions. Lady Franklin herself suppresses her own desire to love Mathinna like a daughter, to “dress that little girl up and tie ribbons in her hair, make her giggle and give her surprises and coo lullabies in her ear. But such frivolities, she knew, would only ruin the experiment and the young child’s chances.” Lady Franklin, caught within the perspective of modern European Enlightenment, fights an interior battle between expressing her love for the young girl, and acting within the normative confines of civilised society: “She could not believe her own lie, her cruel crushing of her own desire, yet believe it she would.”

Predictably, Lady Franklin’s experiment fails and Mathinna is left between a white, European culture she doesn’t fit in to, and a black, Aboriginal culture that has been systematically destroyed by the colonial project. John Franklin’s position as Governor is revoked and he and Lady Franklin return to England. Knowing that “her great experiment was the most ignominious failure, and that she must not suffer the further humiliation of taking Mathinna home to England,” Lady Franklin abandons Mathinna in an orphanage. Once again, she is caught between her humanist passions and the cultural expectations that oppose them and finally comes to realise that “she never admitted what it really was that she longed to know: the love of a mother for a child.”

As the Franklins sail out of Hobart, John Franklin presents his wife with a portrait of Mathinna as a gift: “the portrait,” the narrator tells us, “was marred only by one detail: her bare feet. For Mathinna had, typically, kicked off her court shoes for the sitting.” The final assertion of Mathinna’s bare feet shows her refusal to concede to the expectations of ‘civilised’ society. Mathinna’s refusal to wear shoes is an explicit rejection of the cultural change enforced upon her by the Franklins. Undeterred, John Franklin has the painting strategically framed to conceal Mathinna’s feet. Nevertheless, Lady Franklin throws the painting overboard where it “quickly drifted away, face down.”

The rest of Mathinna’s short, tragic life is left to play out. She falls into an inescapable cycle of abuse and prostitution that leaves the reader questioning the texts civilised-savage distinction. How, we ask as readers, can a civilised project lead to the ruin of an innocent young woman? The Franklins return to England and John Franklin joins an Arctic expedition to establish a route across the Northwest Passage. The failure of this expedition and the subsequent reports printed in the The Illustrated London News that the crew, stranded in an Arctic winter, resort to cannibalism in order to survive offends Lady Franklin’s ideas of her civilised self and the honour of her husband’s legacy. In response, she seeks the assistance of none other than Charles Dickens “to put an end to these dreadful rumours of Sir John eating his fellows.”

Dickens is similarly insulted by these accusations against English gentry. He reinforces the idea that savagery is an inability to supress individual desires: “he can yield to whatever passion he wishes, but for that very reason, he is a savage—a bloodthirsty wild animal whose principal amusement comes from stories at best ridiculous and at worst lies.” Again, the irony is obvious as the most lauded novelist of the time criticizes others for their reliance on stories while he himself is described as having “loved everything to do with that world of make believe.”

He dismisses newspapers (an ostensible source of fact) as “an ever less satisfactory form of fiction” and invalidates the evidence that led to the rumours, noting that “Murderous thieves produce damning evidence of murderous thievery.” In response, he writes an article that meets such acclaim he decides to produce a play, The Frozen Deep. The play, critically acclaimed, defends the honour of the British expedition. As the narrator notes: “For those who had followed the greatest mystery of the age, the prospect of the most popular writer of the day putting forth his view on the sensation of the rumours of cannibalism was irresistible.”

But this play serves other purposes and over the course of rehearsals and productions, Dickens’ own resolve to defy his human passions begin to falter as he falls in love with the play’s star, Ellen Ternan (also Dickens’ lover in real life). The play begins to breakdown the opposition of reason and desire, in similar ways to Lady Franklin’s relationship with Mathinna. “Dickens realised he was no longer speaking to a script, but that the script was—improbably, inexorably, inescapably—describing his soul.” Consequently, Dickens’ captivates the theatre with his performance and the breakdown of the boundaries between fiction and reality are succinctly identified by Dickens’ friend Wilkie Collins who, watching the performance, describes it as “no longer a play, but life itself.”

Dickens’ play communicates Flanagan’s position on the role of fiction in history. By representing the play and, particularly, Dickens’ performance in such a way, Flanagan is gesturing to the untenable nature of reason as a guiding principle, not only for ‘civilised’ societies, but for life itself more broadly. Reason, in other words, is insufficient as a sole justification for the actions of individuals in the world. This is evident as Dickens, “a man who had spent a life believing that giving in to desire was the mark of a savage, realised he could no longer deny wanting.” Flanagan’s work suggests that if this is true for our reality, then it must be equally true for our representation of that reality, notably in works of history.

Developing History

History is important only insofar as we can learn from it. We build our social and cultural realities from accounts of the past and this process is a dynamic one. As Slotkin describes, “People are evidently not mere victims of inherited myths and ideologies, but have an active role in transforming received culture.” If we play such an active in developing histories, then it stands to reason that we must cast the net as wide as possible as we seek to communicate events of the past. Historical fiction, to extend the metaphor, is an essential section of this net. The voices and the perspectives that historical fiction facilitates are indispensable to holistic accounts of the past. Together, with traditional historical accounts, they contribute to a broader understanding of history that determines our trajectory into the future.

Works Cited

- Flanagan, Richard. 2008 [2016]. Post-script to Wanting. London: Vintage. ↩

- Ashcroft, Bill. “Rewriting History: Gould’s Book of Fish,” in Richard Flanagan: Critical Essays. Edited by Robert Dixon, 87-102. Sydney University Press: Sydney. ↩

- Shaw, Harry, E. “Is There a Problem with Historical Fiction (or with Scott’s Redgauntlet)?, Rethinking History, 9:2-3, 173-195: (2005) ↩

- Slotkin, Richard. “Fiction for the Purposes of History.” Rethinking History 9, no. 2–3 (June 2005): 221–36. ↩

- White, Hayden. “The Question of Narrative in Contemporary Historical Theory.” History and Theory 23, no. 1 (1984): 1–33. https://doi.org/10.2307/2504969. ↩

- Flanagan, Richard. 2016 (2001). Gould’s Book of Fish. London: Vintage. ↩

- Flanagan, Richard. 2016 [2008]. Wanting. London: Vintage. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Good work! I especially appreciate this because I’m letting an idea for an article “simmer.” It would be about MG/YA historical fiction, particularly examples geared toward young women.

As a student of both literature and history, I am aware of the debate regarding whether historical fiction should be used in the study of history. While there is probably little space for it in the formal study of history, I think public history needs this kind of fiction. Studying the supposedly ‘objective’ facts of the past can be boring. Turning it into an emotional narrative and adding human interest, however, can engage readers who are usually disinterested in history. This increased awareness of the past, especially here in Australia, can only be positive.

Also, I am always glad to see Australian history receiving attention in a public forum, so thank you for writing this piece! I had never heard of either of these texts so I am definitely eager to check them out.

An eye opening and though provoking piece. Thank you.

Great article. Gould’s Book of Fish is an incredible work of historic fiction which challenges our ideas of the past, present and future – the book is entirely in a league of its own.

The concept of the book was fascinating, a study of a fish per chapter in the life of a convict in a penal colony of Tasmania.

I was underwhelmed by how the concept was carried out.

There is a mismatch between the author’s writing ability and his ability to tell and invent a story. This is the most boring book I’ve ever read in my life.

I agree. Love Richard Flanagan and really wanted to like this book, but no.

Gould’s Book of Fish is a weird one. It’s funny and gruesome and fantastical and sometimes makes very little sense at all.

Very fun in its concrete literature genre. But exhausting.

Probably the most beautifully printed novel ever.

Loved this book – the concept, the history, the depth of character, and the language.

Flanagan uses an interesting narrative style of writing that reminded me of other 20th century writers like Italo Calvino.

I feel his style wears thin fairly quickly with little dramatic story arc to maintain my interest.

I am a trained historian, interested in colonization and the terrible fates of indigenous peoples, and his books addresses that terrible fate.

I did enjoy reading this, thank you. I’ve not read Flanagan’s work yet and now feel I would like to.

I tried to read Narrow Road, but given that he’d stolen the name of my favourite book I couldn’t get into it and found the characters shallow and obvious and the way he portrayed the Japanese seemed shallow too. Maybe because of my Australianess I also found the imagery of Tasmania and South Australia a bit shallow too. Can’t see why he won the Man… Not sure I’m willing to risk the cash on another of his books…

Richard Flanagan is a great writer and will continue to be one.

I remember reading the reviews of Wanting when it came out, and “wanting” to read it (forgive the pun) – didn’t realise it was the same guy though. May have to check it out now…

I love him so much; his books are such a deep dive into the depth of your soul and being, that I can hardly bear to start them. Then I can hardly stand to leave them at the end.

Fantastic that Richard Flanagan’s work is now duly recognised in the wider world.

Mr Flanagan shows that there are still Aussies who are sensitive and compassionate, despite our current government trying its hardest to depict us as totally soulless and self-interested.

I found the parts set in Tasmania quite interesting (I lived there as a child) but the other storyline about Charles Dickens was a little boring.

I never bought into the idea that there was a much of a thematic connection between the story of Charles Dickens’s collapsing marriage and infatuation with Ellen Turnan and the tragic tale of Tasmanian Aboriginies girl Mathinna.

This book was so well written I didn’t care too much that the two stories never really cohered.

This book wasn’t easy to read, a little like Don DeLillo’s Underworld, maybe a little bit less bizarre, but similar fragmentation and confusion.

I like how Wanting brings in threads of colonialism and societal and gender norms set in Victorian times.

Gould’s Book of Fish A Novel in Twelve Fish is brilliant. It has passages of eloquent honesty about life, love, and tragedy that I will not quickly forget.

This book was not always an easy read. There were times when it hit me with brutal and beautiful honesty and times when it was all too easy to put down.

“Magical realism” is a difficult tool to employ, but he does it very well.

Great article and writer.

Wanting is a marvellous piece of historical fiction.

A good essay, the blending of history and novel is perceptive.

A fine, thoughtful writer and two great books.

I am a huge fan of William Faulkner and I am hesitant to compare anyone to him. But I would compare Richard Flanagan to Faulkner.

I like that you’ve mentioned the Black War. It’s something that I’ve never heard of before and seems like something of interest in earlier Australian History.

This article is very illuminating, thank you for the recommendations and the insight into Australian history.

The first thing that comes to mind is the quote attributed to Mark Twain “ Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; Truth isn’t.”

As a budding young journalist, my mentors warmed me about “truth”. I was told that my version of truth was actually a bias “All truth is filtered through bias. The best you can do is to learn to be fair.”

The danger of historical fiction; Do these works seek to entertain or to sway public perception?

A number of films come to mind when I think of historical fiction.

Three major “historical” movies make a case against the “Victors” writing/presenting history.

Birth Of A Nation; 1915, directed by D. W. Griffith adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.’s 1905 novel.

All Quiet on the Western Front; 1930 film based on the 1929 Erich Maria Remarque. Directed by Lewis Milestone,

JFK: 1991, written and directed by Oliver Stone.

• The Rebels cause was noble, and the Klan was the buffer to the miscegenation of the South.

• Many WWI Germans didn’t believe in their Nations “cause” and the ones who did were monsters

• No matter what legitimate historians say JFK’s assassination was a conspiracy that could have been carried out by any number of people or organizations that hated him

Many other films could certainly be included on this list. What they all include is an alternative view of history that fuels the bias of an audience that seeks confirmation.

Great read! Loved your insight and perspective

My thesis advisor for my history MA once commented on how I seem to prefer my history “fictionalized” so I relate very well to this article. I have also found there to be an interesting dialogue building in the disciplines of archaeology and museum studies that argues that all history is inherently presentist… it seems to really depend on what you think the purpose of history is.