Irene Adler: Forever Feminist

BBC’s Sherlock plays with the character of Irene Adler in a way that updates her to the 21st century. Screenwriter, Steven Moffat, preserved Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s short story, A Scandal in Bohemia, seen in the season 2 première, A Scandal in Belgravia. This is the only short story that features the iconic female character, Irene Adler, who in many scholarly works is described as, “…this beautiful, intelligent and mysterious character, a Victorian woman well ahead of her time.”

However, bloggers such as Isobel ─ the first to write about the episode that aired in January this past year ─ are disappointed in Irene Adler’s representation on the BBC saying it, “…manages to engage in a horrifying mess of feminism-fail by the end.”

Something that is missed in both of these observations is the specific movements of feminism that these portrayals represent. To say that Irene Adler is still progressive in the original text for today’s standards would be a hyperbolic falsehood. What may seem on the surface as “a horrifying mess of feminism-fail” is actually part of the latest third wave feminism, this is demonstrated in power depictions and the essential Woman concept Sir Arthur Conan Doyle seems to suggest in A Scandal in Bohemia. The episode concludes on a far more gender equal note that only third wave feminism could offer.

Third wave feminism is part of an organic evolution of feminist theory. Conceptually first wave feminism is characterized by seeing female characteristics (such as being nurturing, pure, compassionate, etc) as essentially female and better than male traits. Second wave feminism altered this way of thinking by reasserting that the male and female traits are both valid, but are separate. This continued a binary view of the sexes. Third wave feminism sees these traits as culturally constructed. The idea of feminine and masculine traits being innate is eradicated by this wave of feminism. The goal is to break down the binary as humans are all made up of both masculine and feminine qualities. Men can be nurturing and women can be warriors. Gender in this way becomes fluid instead of fix.

The Essential Woman: 1892 Irene Adler

A Scandal in Bohemia was published in 1892 as part of the story collection The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. At this point in the Sherlock Holmes collection, Dr. Watson is married and has not seen Sherlock Holmes in a while. On a visit to Bakers Street to see his old friend Mr. Holmes he gets wrapped up in another case with the assurance that this one will be big. When the anonymous employer arrives they discover that he is the King of Bohemia who is in trouble due to an ex-fling, Irene Adler, who possesses a compromising photograph of them together.

The case involves getting the photograph back from Irene Adler, which proves to be challenging due to the many failed attempts the King has had in capturing the photograph. Sherlock Holmes uses an ingenious disguise and a diversion created by Dr. Watson to uncover the photograph’s location. In the end, Sherlock is tricked by Irene Adler who keeps the photograph but she keeps it simply for security. Although the King is pleased with the result none the less, completely trusting Irene’s word, Sherlock is still beaten for the first time.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in this short story pushes first wave feminism principles by showing Irene Adler from a male perspective. The way in which we are exposed to Irene Adler is from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle writing from the perspective of Dr. Watson observing and interpreting what Sherlock Holmes is doing and seeing. We are dealing with three layers of male narration to uncover a female character. This immediately distances the reader from the gender of Irene Adler and her view-point making it seem gendered in a negative way.

Through this Irene Adler does push for the Woman essence of the first wave feminism thought. This wave pushed that yes, men and women have separate traits, but women traits are not negative traits. In fact, they are on par if not better than male traits. This wave of feminism was at its height after World War I, when women were pushing that The Great War is what you get with masculine traits.

Doyle writes through Watson that to Sherlock Holmes Irene Adler is “the woman” who “…eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex.” This is due to Irene Adler being the one person who beat him and it is by “a woman’s wit.” She was able to tell through Sherlock’s disguise and he was unable to tell through her’s. This could be due to a possible attraction to Irene Adler, which is seen when he only asks for a picture of Irene that she leaves to the King as a reward for the case.

Irene is never forgotten, and is always known as the woman after this. Through the word choices we can see that Irene Adler is not just clever but has the cleverness of women. Making Irene Adler a strong woman, but forever seen as her gender and the exception to the rule. This is first wave feminism seen by a male author in 1892 before the war making it progressive even before the movement had its heyday.

Modern Woman: 2012 Irene Adler whip and all

Then we move to 2012, where there have been a bountiful amount of adaptations of Irene Adler through literature, television, and film. She has been altered through time and media, but still encapsulates the same amount of progressiveness that she had in 1892 in the BBC hit show Sherlock in 2012. Her feminism has just been updated to third wave feminism that is still being defined today. Third wave feminism looks at feminine and masculine traits and how they are culturally constructed. These traits are no longer seen as innate and there is no longer a female essence, something as uniquely feminine or masculine.

The plot of the episode A Scandal in Belgravia starts with Sherlock and Watson’s close escape from Moriarty, wrapping up the cliff hanger of the first season. Their next exciting case is from an anonymous client whose daughter has had photos of herself in many compromising positions taken by Irene Adler, a dominatrix.

Sherlock and Watson are assigned by Mycroft, Sherlock’s brother, to recover these photos. After their first attempt fails, they try many more times only to fail again. She is the only one to get away and taunts him with flirtatious texts. The photos are kept in her possession for protection and not for any sort of bribe. However, the twist is that she is working with Moriarty to bring a nation to its knees through helping terrorists avert a British government plot.

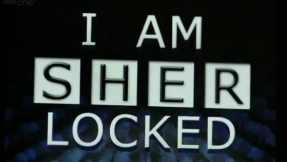

In the end she is foiled by Sherlock, when he finds the password to her phone that holds all the information including the pictures. Every time the phone said “I am _ _ _ _ locked.” Her password turns out to be sentimental and prove that Sherlock was not sad for thinking she had feelings for him when the screen reads, “I am sher locked.”

Although from afar, the plot seems vastly different, there are similarities to the original text that are cleverly made homage to in the 2012 adaptation. Irene Adler is still The Woman, although this is her dominatrix name on her website. She is also still has photos of a royal person. In this version they are of her and a female royal person making it even more progressive for Irene is openly engaging in lesbian sexual acts.

The scheme Sherlock construes to find the compromising photos is very similar to the original text. Sherlock still is injured with blood on himself whilst disguised as a priest to get into her home. Once he is in there Watson starts a magazine on fire to trigger the fire alarm, which like the text makes Irene Adler think her house is on fire. By doing this they hope that her eyes will go glance at the photos revealing where they are hidden.

In the show Sherlock says to Irene, “When a fire alarm goes off a mother looks for her child. Amazing how it shows our priorities.” This is similar to the text, although made contemporary, when Sherlock says to Watson, “When a woman thinks that her house is on fire, her instinct is at once to rush to the thing which she values most… A married woman grabs her baby; an unmarried one reaches for her jewelry box.”

Again the quote is revised not only updating to a fire alarm, but to not saying a married woman automatically has a child and an unmarried woman only cares about jewels.

Some broader things are kept in the episode from the original text. At the end of the short story Irene Adler keeps the photographs for protection from the King. In the television show she needs her phone with the picture and other information for protection. The phone is her life and is a signal of her death if it is not in her possession.

In both it gives Irene Adler power over others by being the one privileged to information. Over all she is always the one that got away and to Sherlock is the woman. Sherlock in the show is far more obviously infatuated with Irene Adler but also proves that she is just as infatuated as him; making the woman more significant. She gets away with the help of Sherlock when she was about to be beheaded by terrorists, which is the point in the show where some viewers say that the show is no longer having Irene Adler be a strong and independent woman. However, this is false and will be fully evident once we explore how this show represents third wave feminism.

Sherlock splits from Doyle

Before that we must show where the points of departure happen in this episode. A huge break from the stories is seen in the romantic relationship dynamics that happen between the characters. The television show directly addresses Sherlock’s inexperience with women through Mycroft’s snide comments and Moriarty’s nickname for Sherlock, the Virgin. Irene tries to capitalize on this aspect through her own comments and becomes cold to Sherlock.

She puts on a whole charade to convince people that she manipulates Sherlock the entire time and has no real feelings towards him. Although she does manipulate Sherlock and have power over him, she also does have feelings for him in the end. This is shown through her sentimentality in the password for her phone. This is vastly different from the original text for in A Scandal in Bohemia she is engaged before Sherlock ever meets her, and never shows reciprocating feelings.

At the same time three other relationship dynamics are happening. Molly Hooper, who works in forensics, is desperately in love with Sherlock. A love that is filled with pathetic jealously for Irene Adler, a woman he identifies in the morgue by her body and not her face. Then we have Dr. Watson’s ever failing relationship after relationship due to his involvement with Sherlock. Many in the show reference to them being a gay couple due to their amount of time and dedication to one another. John’s girlfriend in the episode says, “My friends are wrong. You are a good boyfriend…to Sherlock.” Later when Irene Adler says that Watson and Sherlock are in a relationship, Watson responds, “If anyone still cares, I am not gay.” Not only is this a huge departure from the stories by Doyle, who does not meet these homosexual undertones head on, but they play with different gender traits.

Watson in the way he takes care of Sherlock is seen as having more traditionally feminine traits, while Sherlock and Irene go back and forth in their feminine and masculine roles. This is in stark contrast to the heteronormativity in the original text where Dr. Watson was already married at this point. Another piece that plays on this is that the show explores Irene Adler being a lesbian who participates in sexual activities with both men and women, making the power exchanges with Sherlock enhanced in her ability to play between the feminine and the masculine. As we delve into Irene Adler’s character and her mixed feminine and masculine traits we will see that her later reliance on Sherlock is not one of inferiority, but of equality that they share throughout the episode. By mixing these traits up with each character the show is using third wave feminism.

Plot wise the big departure comes from the pictures were not the point of Mycroft needing the phone recovered. This is made clear when the CIA bursts in during the first scene where we see Irene and Sherlock interacting. We discover that there was going to be a terrorist attack and the British government knows about it and was going to play a trick making the terrorist think they succeeded. In actuality, it was all going to be an act. However, Irene Adler collaborates with Jim Moriarty, Sherlock’s arch-nemesis, to uncover this to bribe the government. Sherlock unbeknownst to the scheme, helps Irene Adler crack the code in an e-mail that reveals the government’s plans. If Sherlock can get access to her password he can redeem himself from being tricked, which he does by revealing Irene’s true feelings for him. This is the one moment we see Irene Adler not hiding behind a guise or mask as tears well up in her eyes as she realizes she has lost. Despite the loss she still manages to escape and fakes her death a second time. The second time she does not trick Sherlock but is in on it with him making Mycroft’s line that much more satisfying when he says, “It would take Sherlock to fool me. But he wasn’t on hand.”

A Dominate Irene Adler

The scene for close analysis is when Sherlock Holmes and Irene Adler meet each other for the first time. This scene is great for demonstrating Irene Adler’s modern portrayal of current third wave feminism. Sherlock enters her home in a disguise and she walks in to introduce herself fully naked. At this Sherlock cannot read her like he does everyone else. He is shocked and unable to draw conclusions. Her disguise here is far more active than the one from the original text.

In the 1892 version Irene Adler at one point dresses up like a man and passes Sherlock on the street. When this happened it went unnoticed by Sherlock, although it should not have due to his knowledge of her having acting experience. The short story version of this is more passive and involves Irene Adler becoming more assimilated into the societal normatives. It suggests that the male is the normative sex and the only way to not be suspect.

The 2012 version of Irene Adler is more active. She immediately sexually intimidates him by putting his clergy collar in her mouth. As she sits down covering all the right places with her arms she reads right through his disguise and divulges information she has on him; knowing where he has been and how he got there. Not only does she then intimidate him with her brash nakedness, but through her knowledge.

Sherlock reassess the situation now knowing that he is dealing with someone on equal grounds. The only others to do this have been Mycroft and Moriarty. Once she puts on Sherlock’s coat at Watson’s behest she asks about the other case Sherlock has been working on saying, “Brainy is the new sexy.” In this moment she continues to command dominance in the conversation without having to be naked. Sherlock officially calls her “moderately clever” which is a big compliment from this version of Sherlock Holmes. By this point she has asserted her intelligence and verbal dominance. This sort of control over a situation is typically seen as more masculine.

As soon as she loses this dominance when Sherlock tricks her into revealing where her phone is, she reasserts a different form of dominance fairly quickly. CIA agents burst into her home threatening to shoot Watson if Sherlock does not open the safe that holds the phone. Once Sherlock unlocks it, he figures out there is a trigger inside to shoot, so he ducks causing it to shoot one of the agents. He signals to Watson and Irene to start disarming the agents. Irene does so effortlessly and whacks a CIA agent with the gun she confiscated.

She continues to physically dominate when she stabs Sherlock with a needle to make him pass out. She continues slapping him with her dominatrix whip till she is able to get her phone back. This is how she gets away the first time and enters a more typically masculine role than she ever had in the original text.

Ms. Adler is no femme fatale or damsel in distress

In many aspects Irene Adler in this adaptation fits the classic femme fatale role, but where she breaks from this pattern is where the third wave feminism redeems her character. Victoria Lynn Schmidt in her book, 45 Master Characters: Mythic Models for Creating Original Characters, outlines the femme fatale. Two main characteristics that Irene Adler in the television adaptation shares with those Schmidt outlines are her use of her body as a weapon and her ability to deliberately manipulate others with her sexual promises.

We see this a lot and in the adaptation this is accentuated by her role as a dominatrix. She divulges throughout the episode how she got information from powerful men. Whenever she is asked if she knows that man (whomever he may be that she extracted information from) she responds with, I know him…Well, I know what he likes. By her being a dominatrix she can be sexual but in this place of power she puts men in vulnerable positions both figuratively and literally.

Irene Adler’s control grows in power through her interactions with Sherlock Holmes. In this adaptation, Sherlock has very little experience with women in the area of romantic intimacy (or intimacy of any sort with any gender) and characters point this out throughout the episode. Irene Adler is able to intimidate Holmes through her social experiences.

The scene where she walks in naked is not just a way of disguising herself but confronts Sherlock with something to make him feel uncomfortable due to his inexperience with women. With just her presence she is able to make the hero of the show stumble and forget himself. Leading up to this point in the series Sherlock has been able to solve every case and has never been used. He is always able to figure people out, but this woman through her sexual prowess and intellect is able to fog Sherlock’s mind and deceive him.

The feminist dilemma arises when Sherlock is able to overcome being hoodwinked by Irene Adler. Blogs have complained that her feelings for Sherlock and reliance on him to save her life at the end of the episode make Irene Adler the damsel in distress. This would be a logical conclusion if not for the rest of the episode.

The femme fatale role is typically one who does not have any feelings for the man she is trying to manipulate and can only use her powers of seduction to have control over men. The latter has already been proven that Irene Adler strays away from this pattern in the close scene analysis. She is not only able to manipulate but is physically strong enough to get out of a bad situation. Irene Adler is not left defenseless if her charms fail her. Her charms are simply something she accesses in order for her to not get her hands dirty.

The former point is proven to be folly in the way critics think that a female character must be cold and heartless to have strength in a patriarchal world. By Moffat writing for Irene Adler to find her equal in Sherlock and fall for the innocent (virgin) man he is actually switching typical gender roles and enforcing a message of equality of those genders by blurring the gender binary. In having Irene Adler care for Sherlock and vice versa we see that the only true equal to our intelligent hero is an equally intelligent female.

Irene Adler is different from the typical femme fatale (calling in all third wave feminists). In the original text the woman was strong because of her essential female qualities defeating Sherlock Holmes. The female essence is what supports the femme fatale, for stereotypically a woman is physically weak and the only weapon at her disposal is her power to manipulate men sexually. Although the 2012 Irene Adler carries this in her character she is not left defenseless without her ‘womanly ways.’ Male characters on the other hand are manipulative and physically intimidating. Irene Adler comes in joining in on the manipulation and intimidation not as a woman, but as another central character in the plot. Of course, she cannot be Wonder Woman and Sherlock cannot be Superman. They each along the lines of third wave feminism have equal amounts of strengths and weaknesses.

Third Wave Feminism Brings in a Feminist Sherlock Holmes

What makes an audience so invested in the Sherlock and Irene relationship is that they share some similar weaknesses. Both are unaccustomed to having deep feelings for another person and expressing it. Although the difficulty in expressing their true emotions comes from two very different origins. Sherlock has trouble with this do to his personal lack of intimate communication with others and Irene Adler is made uncomfortable due to her wide array of experience in the use of artificial intimate communication.

Both of them have the strength of disguising what they actually feel, which becomes their flaw when they interact with each other. Due to their feelings for one another they have difficulty keeping up with their disguises making it possible for the other to read them. The key moment when Sherlock flubs is when he cracks the code for Irene Adler, allowing himself to be fooled in giving away government secrets to impress Irene. She then makes the mistake of letting Sherlock take her pulse during an interaction with him. Just as Irene ruined Mycroft’s plans, Sherlock is able to ruin Irene’s plans. In this way they have arrived at an impasse.

When Sherlock Holmes saves Irene Adler from terrorists at the end of the episode (letting the viewer know that she is still alive and Sherlock knows this piece of information) is the major problem some feminist critics have had with this adaptation of Irene Adler. It seems like this ending is implying that Irene Adler is in her ‘right place,’ for in this scene she is defenseless and reliant on Sherlock. This is an inaccurate observation.

If we are to remember what happened half way through the episode it becomes obvious what this scene really meant. During the episode Irene Adler fakes her own death leaving Sherlock devastated. However, he eventually finds out making him feel humiliated that he was made a fool and left vulnerable. Their relationship here is one-sided with her on the top (no pun intended). But when Sherlock is in on the scheme the second time Irene Adler fakes her death, he is then no longer inferior to her.

Instead of being tricked by her false death another time, he is then in on the scheme with her: making them equals in their shared privileged knowledge. Thereby making this scene back away from the older feminist concept of women not needing men for anything and entering into a gender symbiosis relationship of equal reliance on one another.

This again is vastly different from when she had previous knowledge of him before their meeting that Sherlock was not mutually privy to. For most of the episode Irene Adler has the upper hand, but instead of Sherlock dominating her in the end they become equals. In the 1892 original text they are put on the same level at the end. She is the one who got away. Except this is a message of separate, but equal, which as we know is not a true sense of equality. Although Irene Adler got away in the short story there is still a separation of the genders and it would not be the same if it was a man. In the adaptation on the BBC, the end presents an actual equality of sharing power, and masculine and feminine traits. Thereby demonstrating a need to help and rely on one another equally with neither being superior to the other.

These characters are able to set up both feminine and masculine traits in their different forms of ostracizing societal normatives by being on the fringes of their set societal roles. Sherlock, instead of being a detective at the local police station is reclusive in being a consulting detective. In this way he is able to do the work without becoming a full part of society. Holmes is then able to stay away from the society enough to not assimilate; thus leading to his comfort with having more feminine traits. Irene Adler by being self-employed releases herself from the shackles of society and makes her the escape for those who are the fully assimilated: the rich, powerful, and political. By being a dominatrix and asserting power over them she is making a statement of how she is above these societal constraints. She then takes on more masculine traits through this control.

Through their place on the fringes of society they are able to create a relationship of gender equality. In this way Sherlock on BBC is able to promote a form of third wave feminism. Thereby, seemingly separating itself from the original text and its first wave feminism thinking. The BBC version of Sherlock Holmes is actually keeping with the spirit of the progressive feminism of the 1892 original. For feminism in 1892 is vastly different from feminism today and would have been terribly outdated. In order for Irene Adler to stay as a progressive female character she needed to be updated to a woman progressive in our time. Thus, resulting in the Irene Adler we see in Sherlock.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I only started watching this show last week. I can safely say this is by far the best thing on British TV. I might even go as far as to say it’s the best thing on TV in general. It’s clever, dramatic, and just the right ammount of funny. I don’t know why it’s taken me so long to give it a go, I’d heard nothing but good things about it, but I’m glad I finally did. I really enjoyed the movie (not seen 2nd one yet) but this is so much better. If you’re just reading this article out of curiosity and haven’t seen it yet, WATCH THIS SHOW!

I’d argue the the modern interpretations are an extrapolation of the character into a modern setting. We must ask these questions: what defines an independent woman in our culture; what defines moral bankruptcy in our increasingly globalised society; what effect does the modern interpretation of Holmes play in defining the character of Adler?

Interesting! I really liked that you discussed Doyle’s Irene. I knew nothing about her original incarnation. I also appreciated that background you gave on third wave feminism. This was informative as well as engaging. Thank you!

Thank you for this article! I adored this episode, and share the sentiment that the those who denounce it as anti-feminist are kind of missing the point. I thought the article was interesting and very effective in the way defined the characters were defined as mixtures of “feminine” and “masculine” traits. This is fascinating because it really does tie into the aim of feminism as equality for not just women, but also for the very definition of traits so they need not be proclaimed inherently masculine or feminine. I also liked the way you legitimized the modern liberties that Moffat took from the original work, not only did the adaptation make for an interesting power dynamic but it also was inherently visually captivating and really took advantage of the medium of film without being raunchy or overtly sexual for the sake of sex appeal. Instead it managed to transcend what could have been an almost pornographic display, into an battle of intellects between well rounded characters. Great read!

New Sherlock is brilliant. Some of Moffat’s best writing to date.

None of the modern adaptations do the character Irene Adler a disservice by distorting her into a villain, rather than an audacious woman who lives by on her own rules but still maintains a moral character. Personally I prefr the modern spin off book series by Carole Nelson Douglas. The first book is a retelling of “A Scandal in Bohemia” from Irene Adler’s perspective.

I will have to read that!

I love that you explored “first wave feminism” vs. “third wave feminism” in interpretation. I did not realize there was so much heated debate about Irene Adler as a feminist because, personally, I loved the power she had over Sherlocke from the moment she appeared. She is a character made up entirely of herself (if that makes sense) as opposed to the film version of Irene Adler (Rachel McAdams) who is so powerful but is instantly demeaned by being placed under Moriarty’s control.

I also love that give you give credit to her affection for Sherlocke. I feel like it’s too easy (particularly during the women’s liberation movement decades ago) to think of “affection” as “wrong” for women, when in reality it definitely goes against gender equality. Watching BBC’s version of Sherlocke is like a window in which we can see a bright future. I long for the day when people can see gender as a total construct as opposed to a “separate but equal” or a “dominant” factor.

I wasn’t a huge fan of Irene in the show or the canon because I feel like she was very enriched- she was just proving a point and being a somewhat stereotypical ‘strong female character’- but your article really hit my inner feminist. I liked it a lot. Very good job.

I usually tend to believe that everyone has made too much of the Adler character given the fact that she only appears once in the canon. Usually fans try to make Holmes’ relationship with her into something romantic and that violates the integrity of the Holmes’ character. On the other hand, I do like the new BBC Holmes and I’m willing to accept the way they play with the Adler character.

Ultimately, however, good as Cumberbatch is, Jeremy Brett will always remain for me the REAL Holmes.

Mr Moffat has written one horrible version of Irene Adler! You don’t add much to this cardboard cartoon version either, so let’s hope Sherlock excises you from his hard drive.

I will say that I did like this episode and its adaptation from the original.

However, I do think that this incarnation of Irene is misogynist, but not because she needs to be “rescued.”

I loved that they modernized this progressive, strong, independent woman into a dominatrix. I love that she is able to be comfortable and confident with her sexuality to a point that she uses it as a means of income (and security). It’s her choice, she’s happy, she supports herself in this mean, corrupt world by “misbehaving” — defying social expectations of how a woman is supposed to act.

My admiration of her character soured only once. Instead of being the woman who beat Sherlock Holmes (you know, in the figurative sense), she falls victim to his seductive charm. And this is a woman who has told us she’s gay. So we’re presented with this unbelievable situation: a clever, powerful, gay woman is foiled only because she fell in love with/has a crush on/feels things for a man. Because apparently we can’t have a female character who doesn’t need to trip over herself to be propped up by Sherlock. (Molly is defined primarily by her infatuation with him; Mrs. Hudson by her inability to NOT be his housekeeper; Sally by her need to antagonize him.)

So this is what I find troubling. The canonical Irene succeeded and kept her “security.” But Moffat’s Irene was foiled. And while I agree that perhaps the nature of her secrets was not something Mycroft was going to let get away, her downfall should not have been her inability to resist the male main character.

And, I mean, it is Moffat, and he isn’t exactly known for painting his female characters in the best light.

^THIS. The problem isn’t that the content of the plot robs her of power. A powerful woman can fall in love with a man, obviously. But it lowers her status from Rival, an equal status, to Love Interest a character who exists to react to and provide meaning for another character

That said, if Moffat can bring her back not as a Love Interest but as a Person Who Is In A Romance Among Other Things then I will be really really happy.

Hell, I’ll probably be happy either way. I love Irene.

I enjoyed your nuanced interpretation! Third-wave feminism may be synonymous with postfeminism in that the latter discourse celebrates the female character’s agency, independence, and joie de vivre–all of the characteristics BBC’s Irene Adler seems to display in abundance. For more on postfeminism, I recommend Yvonne Tasker and Diane Negra, eds., Interrogating Postfeminism: Gender and the Politics of Popular Culture (Duke University Press, 2007). Angela McRobbie, in her essay, refers to the supermodel Claudia Schiffer, who takes off her clothes in a TV advertisement, which she does out of her own choice and for her own enjoyment; “the shadow of disapproval is evoked (the striptease as a site of female exploitation) only instantly to be dismissed as belonging to the art, to a time when feminists used to object to such imagery” (33).

Lara is fantastic. More Irene, please!

This was definitely an all encompassing article. I love Sherlock. And Irene was a nice change in the typically male landscape that is television/the tales in the life of Mr. Holmes. I think my biggest concern with this interpretation, however, lies upon its contingency with third wave feminism being as you described it. The truth (and ultimate struggle) of the movement is that the third wave is continuously debated as to how exactly it can be articulated in colloquial, or even academic, terms. Feminism is still a process and the third wave is real, but the model presented for this analysis of Irene Adler is problematic simply because the third wave has yet to be established or understood fully.

That is the fantastic bit about theory. There is not one that has ever been fully concluded. Every theory is in constant debate and will never have one definition. If it comforts you, you can see this article as having an additional argument as to what exactly third wave feminism can be defined as.

First off, great excerpt! It definitely drew me in and made me want to read the article. It’s been a while since I’ve seen Sherlock, and I’m not a huge fan but I’m interested in anything regarding feminism.

I am a fan of the Sherlock show and Irene Adler is one of my favorite characters so I was really interested what your interpretation of her was. I’m glad you addressed Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s version of her because I had no idea what she was like in the book. I always thought of the show’s depiction of her to be a strong feminist character, probably because I am only really familiar with the third wave of feminism so I like that you made a very intelligent case for her being a feminist character. I also appreciated that you gave a quick overview of the waves of feminism because it really helps put both versions of Adler in context. Really well written article!

I really like the character of Irene Adler in the Conan Doyle cannon and I enjoyed the SHERLOCK episode with her, but I am actually not that big of a fan of her portrayal. Making her a dominatrix seems to undercut her status as a strong, female character by making the locus of her independence and power within her naked body. I do not think she had to be so sexualized to convey independence and agency.

Great analysis of the evolution of the Irene Adler character, and of third-wave femisism. I particularly like the exploration of masculine and feminine traits contained within Sherlock, John, and Irene. Thanks for the work you put into this article!

She is positively delightful and the chemistry between Benedict and Lara is off the charts.

This is so refreshing! Seeing as I haven’t watched the show, I’m not quite up to date on every aspect mentioned in this article, but it provides positive and informed information on feminism. I definitely plan on watching some episodes now.

This is one of the best articles on tv that I’ve read in a long time – really, it’s perfect! Irene Adler has been fascinating me from the first time I saw A Scandal in Belgravia and continued to do so when I had read A Scandal in Bohemia. You managed to describe in the most accurate way why she’s a great example of modern feminism as well as initial feminism. I never knew about the three waves of feminism either, so this article was quite informative in that way too. And I just have to say this even though I sound like a teenager in love, but you have a fantastic writing style!

I enjoyed the way you drew out the historical aspects of Irene Adler as character. Doyle would not have been very invested in exploring the layers and depths of female characters, I claim, and thus his women are usually quite flat and one-dimensional. Much like the updated Sherlock, Irene was on point as the new new “super-villainess” and like you I enjoyed the producers’ walking the fine line between sexualization and a battle of great minds. Well done!

This was so good. I love the show and you articulated your analysis clearly in a way that Sherlock fans can understand. You could go so much further with this study and in gender studies. What does Sherlock and Molly’s relationship say and also his tryst with Janine in Series 3 and how he uses her to get information and access. Irene in both Doyle’s and BBC’s is very mysterious and, as you said, a lot about feminism and its portrayal in the 19th century and the 21st century. This was very well written and coherent.

You might have noticed from the previous episode that she saved Sherlock’s life to begin with and without his knowledge. He saves her life in the end to pay this unfulfilled debt. In this way he reacquires his stature but remains tied to her through the exchange of mutual gifts. You also don’t consider the possibility that they consummated their relationship physically after he saved her although in point of fact this at one level seems superfluous.

Excellent analysis of Irene’s character throughout “A Scandal in Belgravia;” I, too, did not take offense at the episode, but instead enjoyed the verbal sparring between the two. I particularly enjoy your breakdown of their mutual weaknesses: struggling to disguise their own feelings, almost wearing a “masculine” mask to cover up what has culturally been considered a “feminine” trait. Considering that a good portion of Sherlock’s character development has been about opening up to others and expressing more of his feelings, are we seeing a sort of submerged first wave feminism where “feminine” traits are being seen as equal to masculine traits? Unsure. But I thoroughly enjoyed your analysis. What are your thoughts on Irene’s cameo in Sherlock’s Mind Palace sequence of season 3, episode 2 (“The Sign of Three”)? Interesting that Irene appears (and not for the first time, it is implied) when Sherlock is trying to figure out a case and understand the minds/perspectives of women to solve a case. There could be a point to be made about the number of screens he has open with a separate laptop for each chat-room, indicating the plurality of women’s identities, particularly in an increasingly online world…but that’s a whole separate entry :). Thanks again for sharing your ideas.

I love the show but I find many of the female characters to be very problematic. While they generally are all intelligent and independent women, they tend to rely on the men in their lives to save them, physically and emotionally. There is nothing wrong with a woman being in love with a man (it can even be empowering), but it becomes problematic when it causes them to be weak or change who they are.

My problem is still the criminalizing and sexualizing of Irene Adler in most remakes including Sherlock. It sends the message that “strong and independent” must also mean “criminal and/or promiscuous”. And yes, that’s problematic however you try to apologize for it.

If it had only been Irene, I might write it off as an interpretation of “adventuress”, BUT they did it to Mary too. She can’t just be a smart lady. She has to be a criminal and use sex to get close to her target.

A Scandal in Belgravia is probably one of my favorite episodes of the series so far. I thought Irene’s character was refreshing in the sense that she brought on a completely different side of Sherlock which was so intriguing to watch. I enjoyed watching how their relationship played out, and I definitely enjoyed this article. Thank you for sharing your knowledge of the different aspects of feminism as well as the background of the original story!

Loved this article. When we see Irene and Sherlock interact for the first time, I think it’s super important that the cinematography refuses to typecast her as a femme fatale; the camera doesn’t show her full nudity, but instead focuses on Sherlock and John’s reactions to it. In this sense, it also seems to stray away from first wave feminism (your explaining them was super helpful!), as the female qualities are not seen as stronger than male ones.

I agree with the argument that this proves the pluralism of feminism rather than lets it down. I am also interested in the intertextuality of Sherlock with Luther and the character of Alice Morgan with Irene Adler.

I am just learning about the three waves of feminism and this article made perfect sense to me. The BBC interpretation presented the pluralism of third wave feminism perfectly. I am also interested in the intertextuality of Sherlock and Irene with Luther and Alice Morgan which might make an interesting essay.

I have loved this version of Conan-Doyle’s Sherlock since the first episode and in many ways, have been disappointed lately (post series 4) at how much the writers paid homage to the fan-fiction and little in-jokes about who’s gay and who isn’t, not to mention Sherlock and John’s love lives (together or apart).

Scandal in Belgravia comes at one of the shining moments (for me) in the series, when we realize that Sherlock is capable of emotion and even love, whether or not he feels that for Irene. I was originally put off by her role as a dominatrix since it felt unoriginal and that lifestyle has never appealed to me.

Then I realized that I was being too judgmental, luckily! By not judging and simply absorbing a very well-drawn, complex character, not as a woman, a sex worker (as Mycroft calls her) or even as a feminist—whatever wave it is—I was able to enjoy the episode much more. It was confusing, complex, multi-layered and did not leave us with a pat explanation for anything, which is a big reason why the show is so great (or at least in Series 1-3).

This appealed to me because, back in the days when I was exploring second-wave (this term is really too narrow!) feminism, I was irritated by the strident attempts to define men or women as this or that thing, or having these qualities, as being better or worse than one another. It is true that there are some apparent inconsistencies, such as her statement to John that she’s gay and thinks he is, yet she is obviously attracted to Sherlock. Even so, who cares? Can’t people experiment? If anyone would, it would be Irene!

When I read the original story long ago, it really bothered me that after all Irene’s cloak and dagger running around and outwitting Sherlock (no small feat!), her only desire is to run off and get married! Yes, it was the end of the Victorian era, but other authors, such as John Galsworthy in “The Forsyte Saga”, created memorable, independent women in the 1880’s, who did not depend on a man to live a full life. I can safely say that Irene’s version of an “adventuress” made up for the rather uninteresting Irene Adler of 1892!

I agree with your take on third wave feminism and suggest that there are no “waves” in feminism at all, any more than there were in the Civil Rights or Anti-War movements, for example. I see these as a continuum of experience, learning, activism and yes, some periods of setbacks, such as we are going through now in the U.S., not just with anti-feminism and racism, but a general backsliding toward uneducated, nationalistic jingoism. I believe Hunter S. Thompson predicted it, calling it “The New Dumb”! Let’s not let it win!