Is the Novel Dead?

Questions pertaining to the traditional idea of the novel in today’s literary society are becoming an increasing topic of discussion. Due to the rise of numerous sub-genres of the novel, critics and scholars–as well as readers–have begun to question the longevity of the novel. Yet, the novel has been a facet of the literary tradition since the year 1010, with The Tale of Genji, and continues to thrive amongst contemporary readers. Before digging into this newfound issue of whether or not the novel has been replaced, or killed off by newer concepts, let us first begin an inquisition into this proposed threat to the novel by attempting to first define the word, “novel.”

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica Online:

“A novel is an invented prose narrative of considerable length and a certain complexity that deals with imaginatively with human experience, usually through a connected sequence of events involving a group of persons in a specific setting. Within its broad framework,the genre of the novel has encompassed an extensive range of types and styles: picaresque,epistolary, Gothic, romantic, realist, historical.” (Burgess)

The earliest forms of the novel were composed of letters, also referred to as the epistolary novel. Over the evolution of time, literature changed and encompassed new ideas of what a novel would reflect. At times, the influence was political, social, or economical. Gothic novels were thought to be political works that utilized aesthetics as a form of expression. For example, American slave narratives drew upon the format of the gothic novel, while discussing aspects of political concern. According to Frederic Jameson’s Political Unconscious the idea is to always historicize; people will always approach a text with preconceived notions, which is a topic of concern and interest for literary scholars.

The topic of ‘preconceived notions,’ plays an integral part when the changing format of the novel is put into question. Yet, in the context of history, there have been numerous sub-genres of the novel, and this an important concept to recognize when making such a strong assertion such as a fear the “death of the novel.” The novel is not dead; it is evolving to fit with the demands of contemporary readers and the changing aesthetic aspirations of writers.

In attempting to understand the perplexity faced by those who view the state of the novel in peril, a work such as House of Leaves (2000), by Mark Z. Danielewski, immediately comes to mind. The work is classified as a novel, which has left many in an uproar, as the format does not comply with the normal standards of what a novel should look like.

Oddly, Vladimir Nabokov published Pale Fire (1962), a 999-line poem, which was released–and continues to be referred to–as a novel. Is the problem not the actual changing of the novel form, or the fact of the changing face of the novelist? Danielewski publishes his work and many literary critics provided a very cold reception to the work; whereas Nabokov publishes 999-lines of verse (not prose, which is part of the defining factors of the composition of a novel) and it is still deemed a novel. Would this be the case for an up-and-coming novelist, or would their work not be considered a novel?

This leaves two questions: 1. Who decides what constitutes a novel? and 2. Does an author have the right to decide how he or she wants the work to be categorized?

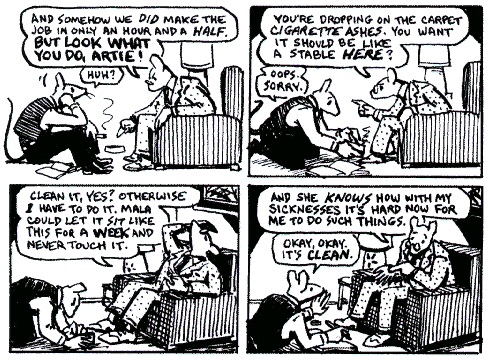

In discussing the changing format of the novel, an important work to mention is Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1980-1991), a serialized graphic novel depicting Art’s father relating to his son the atrocities that took place in Auschwitz during the Holocaust. The novel is unique in an array of aspects, including its minimalistic graphic renditions that relate such horrific events.

Taking a page from old Medieval Tales and even Fairy Tales, numerous characters in the book are portrayed as animals, as a means of further separating perpetrator from victim (the German soldiers are cats and the Jewish prisoners are mice). Though the graphics are unadorned with colors, this tactic of representing people as animals captures the immense separation of races taking place, as well depicting a world in which inhumane acts to take place against human beings.

Robert S. Leventhal’s Art Spiegelman’s MAUS: Working-Through The Trauma of the Holocaust discusses both the traditional cannon, as well as the archetypical model for telling stories of Holocaust survivors. Leventhal acknowledges the sensitive subject of Holocaust literature and the notion that it must be represented it in its “highest” form of art. Yet, he also questions this idea of “high art,” and the changing dynamics of this idea. Leventhal then turns to Spiegelman’s work to articulate his point:

My view is that Spiegelman, precisely by utilizing the “comic-book as the textual medium of a story of the Holocaust, succeeds in breaking the “taboo” or “ritualized fixity” of confronting the Holocaust. It also subverts the assignment of the “comic” to a genre of kitsch and “popular culture” in a twofold way: first, insofar as it supersedes the traditional genre in terms of the scope of its presentation; secondly, insofar as it presents a historical catastrophe in a medium usually reserved for hero construction and morality play.

Leventhal describes numerous aspects concerning the ever-evolving format of storytelling; the necessity to provide readers with new aesthetic modes of representation; utilizing a once critiqued medium for its facetiousness to portray a horrific event in history; and lastly, to defy the conventions of the novel.

Instead of viewing the novel as an endangered species, a better outlook would be to view the progressive changes taking place in constructing a novel format that engages contemporary readers. Yes, the novel is changing dramatically and people are turning to different forms of storytelling, but these should be considered sub-genres of the novel, not works focused on the extinction of the novel. Stagnation leads to ruination and the novel is not exempt from this formula for destruction. Change is beneficial, pertaining to individuals, and the novels people read, and enjoy.

Works Cited

Burgess, Anthony. “Novel.” Encyclopedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/art/novel. 5 Oct. 2015.

Leventhal, Robert, S. Art Spiegelman’s MAUS: Working Through the Trauma of the Holocaust. http://www2.

http://iath.virginia.edu/holocaust/spiegelman.html. 1995. 5 Oct. 2015.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

There are millions of great novels out there for any one person to get through. There’s always another book to read and they’ve always been variations on a theme.

The novel is as dead as history is ended.

Meanwhile, life and literature goes on.

It’s the proper editing of novels what has died.

I approach your question, is the novel dead?, in much the same way I approach the question: what is poetry? We see in modern poetry a dismissal of the rules of rhyme, meter, and the rules of poetry. While this produces some amazing writing (Maya Angelou and Gil Scot-Heron come immediately to my mind), it also muddles the very elements which make poetry as a genre so beautiful, specifically following certain restrictions and manipulating words to achieve a unique aesthetic within those restrictions. To make an analogy: if someone were to run from foul line on a basketball court to the other foul line, take flight, and stuff the ball into the basket, an on looker would rightly describe the act as an amazing feat of athletic prowess. However, if the dunking individual did not dribble and faced no opposition, they would not have been engaged in a game of basketball. Why? Because there are rules to basketball; rules which play a vital role in defining the act itself. Is the novel dead? No, I don’t think so. But readers and writers must recognize that when we expand the definition of a novel without end in some quest for ultimate inclusion, we dilute the meaning of novels until the term means nothing at all.

Does that make sense? I apologize if I’m rambling, this is just off the top of my head and your article deals with questions I have often asked myself. Good show. Great job.

Very interesting comment! I agree that the “rules” of the novel “game” need to be understood in order to even use the term (very Wittgenstein!). To that end, I do think the rules are changing, and folks need to consider what the rules are becoming. Its a very postmodern issue here, the rejection of old forms of art to make room for the “new” or the reinterpretation of the “old”. But now we need to take a look around a figure out where that has left us. What are the “rules” to the game, and, if we want to be very very hypermodern about it, do those rules even matter? I think they do, and I think the mean something to you as well. It’s a difficult conundrum, but this article brings up a lot of heuristic questions that should be thought about (if not answered).

I propose that perhaps the novel itself is not dead, but mutating.

Much like modern poetry, the novel is moving further and further away from the structure, form, and void of classic literature. It is a pattern and paradigm that modern works of art are sacrificing intention for appeal and momentary attention seeking concepts that last no longer than a days twitter feed.

The novel is not dead, but it is no longer what it once was.

If the language of evolution is to be used, the question becomes one of determining the pertinent factors in the cultural environment which will determine whether particular mutations will either survive or be rendered extinct through (mal)adaptation.

In order to describe and explain how random mutations in form and style relate to a specific cultural environment requires a struggle for a science of literature that echoes and expands on Kenneth Burke’s call for a kind of sociological analysis of “literature as an equipment for living.”

Such a project must, of course, be built upon some cohesive integration of the insights of social theorists from Marx to McLuhan, and should take heed of the approach of people such as Terry Eagleton.

Whether the results of such an inquiry and analysis will support the “Andre’s” cautious optimist or “luiminousgloom’s” cautious pessimism is an open question that awaits work on the project itself – a project that, I fear, will not attract many toilers until most current fashions have snuffed themselves out.

We may get a hint of when that will be by remaining attentive to the passing parade of criticism and noticing when works such as Marvin Harris’ “Cultural Materialism: The Struggle for a Science of Culture” come up in what passes for literary discourse.

So glad to see House of Leaves get a mention. It’s a fantastic book!

An interesting take on how novels fits into the current landscape. I think that you’re right about nvoels evolving, and that’s defintiely a good thing. All art needs to evolve over time to survive as a medium.

Newly created ideas will continue to appear.

I am happy to be a part of the small minority that finds reading a key element to discovery, but if I am in the minority then so be it.

You can’t make people read, the encroaching forms of Social Media, and easily accessible bite size quotes from the media, are destroying the ability and the need for people to think harder and delve deeper.

If print is dying out (and it isn’t, not entirely) then ebooks have taken over, and how are they not “novels”?

“Print is Dead.” — Dr. Egon Spengler

It’s fun to look at the trashy lowbrow novels that were published in different eras, but I bet it would be even more interesting to read the novels that were critically-beloved in their time and haven’t held up at all.

I always thought reading novels was a way to be alone.

Or as David Foster Wallace said, a way to combat loneliness.

The form might fall out of the public eye like anything else but I think they’ll still always be written, at least in a world where we’re churning out MFA students at the rate we are now

The printed novel might be evolving, as you said, but I dare to say that by calling the novel “endangered” or “extinct,” you justify those who do not read or want to continue the print novel. While many people no longer read “the classics,” they do read print and enjoy fiction. As long as there remains an audience, there will remain authors. However, by telling people that the audience does not exist, they are more hesitant to join themselves are embrace the culture of reading. If we simply teach reading as valuable and stop insisting people are not interested, people will invest in the value of printed lit.

I think everything changes in order for the medium to get noticed. That’s why people publish e-books, because many readers now go on the internet. There is also something called the cell phone novel, but this is more popular in Japan.

There are quite a few great novels being produced right now. The last few years have been great. About 98% of all novels since they became popular were trash. But we forget the trash of previous decades and just remember the brilliant stuff.

Even if it was dying it isn’t that big a deal. I love novels. I love to read. But it isn’t the be all and end all of creative writing. It is relatively new. There is no reason novels are more important than well written television shows, movies, short stories, whatever.

There is no medium that is inherently better than all of the others at conveying serious thought.

At heart, we are all asking the same question : Why is no one buying my book?

It’s like the novel is stuck stylistically or in terms of formal inventiveness in 1920, analogous to part being stuck in the pre modern art era or no Impressionism or abstraction.

It probably doesn’t help that the more modern “experimentation” looks even more contrived, gimmicky, and incestuous in intended audience in narrative mediums than in visual and auditory.

I feel as though a lot of “high culture” types romanticize the past. They don’t see all the pulp fiction or entirely forgettable works that formed the vast majority of published works then just as they do today. The cream rises to the top, more or less, and although we can try and predict what future generations will take away from our present, history has shown that we’ll probably do a terrible job at it (but it would certainly be entertaining fodder for later paleofuturists!). People decrying the “death of the novel” or the “end of music” generally have nothing to worry about.

I certainly agree with Danielle about reconceptualizing the conversation about the novel being dead or about the humanities under attack for irrelevance. Sharp points in the essay taken and largely conceded, yet arguing that the novel form or medium are shifting according to Rosenblatt’s reader response theory or Jameson’s political unconscious and modern information dynamics is misunderstanding the role of theory. I further don’t see a way to map cultural shifts onto form, despite the notes about the epistolary or gothic or “graphic.” Did the novel form change across the 20th century to reflect the radically shifting cultural norms in the US, for instance?

And it’s in the latter – in comics – that we find the most cultural derision, despite all the popularity afforded to comic-book-related film properties. For everything *Maus* has done to advance the legitimization of the medium, it’s also ended the conversation for many. We have broadside ballads and William Blake and Roman pottery and political zines and more that showcase an evolving content in the sequential art medium, and perhaps even the definition of the novel, but the argument here seems to draw too heavily on an implication that the readers are causing the form to change – that readers change novels. Readers didn’t somehow create *House of Leaves* and *Maus* – but the definitions for genre and medium are being, rightly, reconsidered because of more diverse work, far more widely available.

The comics or sequential art medium may be “usually reserved for hero construction and morality play” if one considers only the most mainstream sources offered by the Barnes & Nobles of the world; and while many of my traditionally trained colleagues scoff at *Watchmen* to defend *Beowulf,* they and I celebrate that we (and Danielle) continue to value literary study – and the novel – because of what is timeless, how Mary Shelley and Chinua Achebe and Shaun Tan will continue to resonate with readers because of what they artfully depict about the human condition.

I’ve been to the book store quite recently, and I see no sign of the “novel” as I understand it being dead. More so, I consider the practice of printing on paper a slowly dying and soon to be dead method of distribution, because not only do paper books and hard-bound books take up a lot of space in the home, but they are a 15% more to twice as expensive as a digital copy. Not to mention the fact that trying to hold a 500-1000 page book upright and/or in the dark is difficult, whereas holding an I-pad or a Kindle is better in both respects. It may seem to traditionalist that switching to digital is taking something away from the practice of reading, but honestly I think in my case, it has convinced me to start reading more, and reading full length novels, rather than just short articles on the internet.

By the end of your article, I’m still not entirely sure what you meant to express in terms of recent novels being different than classic ones. I don’t seem to have picked up any evidence from what you’ve written that shows me something has changed, specifically with reference to “House of Leaves.” So I will need to look that one up in order to see what the controversy is. But so far as I can see, books are still being published of decent length, they are still telling fictional stories of characters in a particular setting, and while they may play around with format in order to paint a particular picture in the minds of the readers, I haven’t noticed any sort of pattern or movement in literature which is altering the style of what the novel is and has been for decades.

The questions raised here are very interesting. But in terms of answering those questions, it would be worthwhile to examine not only the production and producers of novels are but also the consumption. When I first read the headline, I was expecting a quantitative summary of declining readership of novels. Though I found this analysis interesting, does it really matter what’s being written– or what it is called– if no one is reading it?

The questions raised here are very interesting. I especially like the second one, because I think authorial intent tends to be way overblown in terms of the true “meaning” of a text and I imagine the same is true for categorization. But in terms of answering those questions, it would be worthwhile to examine not only the production and producers of novels are but also the consumption. When I first read the headline, I was expecting a quantitative summary of declining readership of novels. Though I found this analysis interesting, does it really matter what’s being written– or what it is called– if no one is reading it?

There is a difference between the novel and “high literature.” In other words, it is one thing to read Fifty Shades of Grey and another to read The Sun Also Rises. I am not saying that one is necessarily better than the other, but those who are academia will be more interested in The Sun Also Rises while those reading for simple pleasure would-most likely-be more interested in Fifty Shades of Grey. I believe, when looking at literature, there are plenty modern-day novels that can and eventually will be placed in this category: The Song of Ice and Fire by George Martin, The Lord of the Rings trilogy by J.R.R. Tolkien, Neverwhere and other novels by Neil Gaiman, and Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams.

I think what I appreciate most about your examination about this question is that you do not get caught up in musings over whether electronic books will replace printed ones – as that really is an entirely separate question all-together, but one that I have found gets dragged into this conversation.

Your arguments concerning the necessity for shifts within novels’ formatting for its survival rings so true! We have seen that with all forms of art, and there is no reason it shouldn’t stretch to this realm of literature. Thanks for writing such an articulate, succinct article on this topic!

I agree. The novel really can’t die unless we as a people reach a point where we no longer value living vicariously and/or experiencing things outside of our normal daily lives. I think to an extent we all feel strong urges to experience new things and reading novels is a pretty easy comfortable way for most unadventurous types to do so. I guess it’s possible that in the future we may experience things using virtual reality instead, but I’d like to believe that there will always be people out there who will want to put their own imagination to someone else’s written word.

Does the novel really have a definition? Who defined what a novel is? And if the novel does have a strict definition, without the novel, the the sub-genres of novels would not exist. Therefore it seems like an obvious statement to make that novels needs to be in existence for any other type of sub-genre to be able to be created. The novel has changed throughout history and will continue to change as we go into the future, but die? It’s not possible.

It’s not so much the “death” of the novel as the “changing” of the novel. Ebooks are becoming increasingly common, but they also offer opportunities to publish lengths of work that are non-standard–novellas, etc., that publishers would typically pass over on length alone. Novellas don’t tend to sell as physical books, but people will read cheap novellas on their Kindles. Should weird lengths (say, 45,000 words) be counted as novels? Maybe “novel” is more an umbrella term than a specific, defined thing.

I’m not sure that I buy into the idea that the novel is dying. In spite of the technological advances and opportunities for publication, people still love to hold a book in their hands. Also, the author here points to a few abnormal exceptions to the definitions of a “Novel,” but I don’t think this article defends its own claims with enough evidence to cause a full scale alarm about the death of novels. Thanks for an interesting read.

Critics have been saying the novel is dying for over a hundred years, yet here it is! Without a doubt it’s changing as our society does, but that makes the future of the novel kind of exciting. I find modern experimental novels fascinating, and the future form of the novel will surely be something we can’t quite conceive of yet.

One proof for the continuing indelibly of the novel is its conversation with other forms of media, particularly film. There’s a perception that the novel, print media in particular, is dying yet we see countless adaptations of these novels into highly popular films and TV shows every year. Especially with teen fiction. The novels from which other media are created achieve acclaim by their merits as literature before adaptations; and these adaptations drive increased book sales. Harry Potter, The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, and Game of Thrones all belong to this category. While it often seems that literature is being lost amidst the plethora of emergent new media, the relationship between all entertainment art forms guaranteed that none of them “dies” as it were.

I am curious as to why Maus was included as an example. A graphic novel is not equal to, nor seen as the same as, a novel; is it fair to discuss Maus in tandem with the notion that the novel is dead? Your notion of sub-genres is interesting but would a graphic novel be s sub-genre of novels or a sub-genre of comic books?

I do agree that what we classify as literature has evolved and will continue to evolve. I do give more credit to contemporary audiences, though. We still read full length stories written in the format of novels: Harry Potter, Percy Jackson, The Night Circus, Pride & Prejudice, Far From the Madding Crowd, the Hunger Games, Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary, Jane Eyre, Lord of the Rings, Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy, etc. These novels, from various time periods, are still read and popular today. Most are also available in a digital format but that does not diminish that they are still novels.

As for contemporary audiences preferring digital copies, that isn’t necessarily true. Digital is more convenient but a large populations still prefers print books, 65% of kids age 6-17 (a survey by Kids & Family Reading Report).

The novel is not dead nor is it dying. Shelves full of books will always be more impressive and valued than an iPad or Kindle library.

It is incredibly difficult to define the novel as a genre because one aspect of the novel is its omnivorousness, its ability to consume and transform all kinds of material. One might argue that novels focus on everyday realities. Real people, rather than gods or other immortals. Of course, that’s not quite true. Neil Gaiman’s American Gods has “Gods” in the title! Yet, Gaiman portrays deities in a novelistic manner. That is, he portrays them as people, not the way the gods are portrayed in Greek epic or tragedy. Defining the novel is not so much about subject manner as it is about a certain method–writing about ordinary life.

I agree with your argument about the evolution of the novel and like your ideas. Writers and artists are constantly following and breaking rules, and over time we see patterns and great shifts in trends within all forms of literature. You’ve mentioned a few titles I haven’t read and have written them down to look into!

However, I am curious to know where you have heard or read people stating that the novel is dead. You state that “Yet, in the context of history, there have been numerous sub-genres of the novel, and this an important concept to recognize when making such a strong assertion such as a fear the ‘death of the novel.'” Apart from the small grammatical hiccup, this quote is not cited and so I’m left wondering about its credibility.

As referenced earlier in the comments, “Print is dead has been said and quoted from the movie Ghostbusters. Without some follow-up on your first assertion that this is a topic of discussion around the novel I am a little confused and feel like you have two different theses running at the same time in this piece. Without any reference, I feel as though the focus of this article should be on the evolution of the novel, and maybe a brief reference to a quote of ‘the novel is dead’ being part of your evidence for the former.

Novels will never die–people need to have a narrative space in which to exist beyond the confines of their own mind; that will never change.

As many people commented above, I don’t believe that the novel is dying, but evolving. In a world that is dominated by screens, social media, and quickness, I do believe that the novel has to evolve. Even just looking at different curriculum that I’ve come into contact with, the novel’s evolution is inevitable and for a good reason. In my AP English class, while we were reading Virginia Woolf and Hemingway, we also read Watchmen, a phenomenal graphic novel. My undergraduate English Department taught a course about Vampires in fiction, mostly inspired by the Twilight series. The novel has to adapt, but no it is not dead.

I found your article posing an important question, but I think you could have explored some other areas, such as the idea of the PRINT novel dying. That’s a concept that is becoming foreign to people, reading an actual book.

How could the novel die? after literal oral (or charades) story telling, all thats left is to write your story down. a the novel is not just limited to a printed page of text otherwise “graphic novel” wouldn’t have come about. sometimes people like to say a novel is between x and y word count but that boils down to semantics. a novel is a story told in multiple pieces, organized, and written. I like this idea that its evolving because it is. the novel isn’t dead. not by a long shot.

I think when people address the death of the novel they are most typically referring to how they think that people aren’t reading as much also how they believe that books aren’t selling. Whether or not that is true, I cannot say. However I don’t think that necesarily implies that the novel will die. I agree with this article, I don’t think the novel is dead, just changing.

I wouldn’t say exactly that the novel is changing, and certainly not dramatically – but rather it’s definition expanding. Everything since the Tale of Genji is still out there.

The novel, which is depicted as being born of the nineteenth century, arose in response to the political and ideological contexts. Benedict Anderson draws a connection between the novel and the form of capitalist nationalism which was prevalent during this period of time. The novel’s influence on society included its enablement of the reader to access the past, the present, and the future in simultaneity, if desired. The linearity of time, as Anderson describes, was deconstructed. Thus, the changing landscapes of the novel, which are well described by this article, are due to the even greater disruption of linear time brought about by globalization and transnational connectivity.

I want to begin my comment by saying that I LOVE that you began your article with House of Leaves and Pale Fire. I actually read these books together in my meta-fiction graduate seminar last semester. I would absolutely argue that both of those texts are novels, although they don’t follow the traditional novel format.

Danielewski’s novel, I think, problematizes the way we read. The text’s inherent narrative multiplicity beckons to literary criticism itself. The constant asides are meant to make readers recognize literary criticism as figurative doorways (mirroring the “actual” house’s own doorways) which can detract from purely enjoying the actual act of reading. Nabakov’s novel, also, beckons to literary criticism. Much like Danielewski’s narrative multiplicity, Nabakov’s constant insertion of the editor’s comments also provide these figurative doorways. I think that this very beckoning to literary criticism is not only what makes these texts meta-fiction, but what makes them novels as well.

That being said, I do think that literature in general is advancing toward new mediums to accommodate our own technologically advancing society. The form is being lost, I would say, considering the kindle and other mediums. I have a LOT to say about that. But I just wanted to say that I appreciate your inclusion of those texts!

I would agree that the novel is changing, but I believe that it always has been changing. Some say that there are no “new” stories to be told, yet the goal of every novelist is to do something a little different than what has come before. Deviating from traditional formats is a part of this. There have been whole literary movements (Modernism) centered around novelists rejecting the traditional novel. The changing novel is just a natural consequence of our desire to create new experiences.

This article comes from a very intellectual, “literary-analysis” perspective. It’s not the angle I would have chosen to tackle this piece from, but it definitely appears well-researched and opinionated. Nice work.

With the digital age, I think “mutation” is a good word. There are several new ways to construct narratives, and therefore the intrinsic composition of novels may change. I also wouldn’t say that comics should be normally relegated to superhero stories or morality plays. I think that’s the common view and why many treat them with derision, but they were originally conceived as accessible ways to educate the needy and the young. I enjoyed the inclusion of House of Leaves in the post. Very thought provoking read.

The word “novel” itself means something new—so what better way than always to change into something it was not before? Of course it retains many of its characteristics (usually prose, usually long, usually fiction), but let it change I say into whatever it wants. As an avid reader of Derrida, I think perhaps the problem is in our attempt at always drawing the lines around things—this is a novel, that is not—who knows? I can’t even determine where to draw the line between a “novel” and a “novella.”

Are we confusing print culture and the novel which is a structural form of storytelling focused on the relationship between the individual and the social? Can the novel exist through mediums other than print? Is the manner of consumption and the internalization of the written word similar to the consumption of performance or visual storytelling? Pondering such questions complicates the perception of the novel as a monolithic and rigid form of cultural expression which is outdated or in a state of decline.

The article discusses the problem smartly with cautious. I presume most people are taking the concept of novel here as the book full of texts and this is the reason they read this article. People who concern about traditional storytelling form come to find clues. However, dear author takes a detour and redefines the novels. The article is fairly good with logic and evidence. Conclusion is also acceptable for readers, BUT the concern of text-novel dying out is not discussed. Though the author analysis the problem very well and readers get a chance to know what is the definition of novel based on experts opinions, the answer given to the question stated as title is not satisfying.

It’s intriguing to see how the progressing of novels into a multitude of these sub genres has caused people to think that the novel, as a genre, is dead. This article does a good job of using the metaphor of Maus to show how such experimental forms of literature, like the graphic novel, is an adaptation on the conventional idea of the novel. Since the convention in which the novel is received is ever changing, novels have to continue to adapt in the same ways, in order to be representative of the situation described within the book. I am not as afraid of the novel dying as I am in the readership of books in general dying out.

There are a number of inaccuracies in here.

“the novel has been a facet of the literary tradition since the year 1010, with The Tale of Genji”

Genji may have been the ‘first novel’, but ‘literary tradition’ grew to slowly accommodate prose over a long period of time, so I wouldn’t call it ‘a facet of literary tradition’ – that’s misleading.

‘Literary tradition’ also differs between country and isn’t a unified concept across time. European tradition is vey different from Asian, and so on.

“The earliest forms of the novel were composed of letters, also referred to as the epistolary novel.”

Those weren’t the earliest forms (they began in the 1600s), though perhaps they were the earliest modern forms. You’re skipping the whole of the medieval period despite noting that the novel stretches back to before it.

“sub-genres of the novel”

You’re mixing form and genre, and have been doing so throughout the article. A novel has genres, and genres have sub-genres. A novel is a form, and forms have sub-forms. By confusing this, you confuse the approach to the argument of whether the novel /as a form/ is dying, which is what the quote in question asks.

As for the issue itself, I personally think the novel is dying because everything that could be one in it has now been done in Ulysses. Circe, for instance, is the pinnacle of heteroglossia, which is one of the novel’s greatest assets. No novel since has so strongly evoked a single character’s journey and a multitude of voices, or balanced clarity and confusion so succinctly. And since the novel contains almost every other art form (parts are written in script, verse and musical notation), Joyce’s work suggests that one of the novel’s greatest strengths is what the rest of the arts bring to it.

I think the question itself is problematic. The same fear that writers and readers had in the Victorian era regarding the novel as “low art” is the same fear that writers and readers have now of other types of writing. The expansion of other forms of writing, or sub-genres of the novel does not cheapen the novel.

Literary critics did the same thing during the 1970s and 80s. They felt threatened when theory (feminist, formalist, etc) began to be applied to other forms of art they deemed unworthy. But, critically thinking about how theory can be applied to pop culture, soap operas, music, etc does not mean that it lowers the art forms traditionally privileged.

The evaluation of art is a worthy endeavor, not simply the art itself. The critical thought and reflection should be held up as important and meaningful, the evaluation is the goal, not the classification of writing.

Pale Fire is not merely 999 lines of verse. Most of the novel consists of our hidden protagonist’s dark and whimsical (and unreliable) commentary on that verse. That’s where the heart of the book lies.

Novels and literature itself are not different from anything else.

There will always be place for innovation with new ideas taking form.

The novel, dead? How dare anyone suggest such a thing! But seriously, though, I do like your take on the novel’s evolving format and can appreciate how the novel, as well as how we approach it, has changed. Particularly in recent decades, novels with new formats (graphic, epistolary, etc.) have become more popular. I find them intriguing and, in most cases, as good as or better than novels written in the traditional format.

I wouldn’t think so unless you are referring to the writing quality, in which case it depends on what you are discussing.

No, it’s not.