Masculinity and the Disney Princess

From Disney’s first princess film in 1937 to its latest in 2013, there is no denying that the Disney Princess has evolved. If a person were to pull a Disney princess movie marathon, it would be possible to get a glimpse of Western society’s changing views of gender over more than three-quarters of a century. Disney has come under criticism in the past for its portrayal of women as the typical damsel in distress archetype, which has arguably caused the company to move in the exact opposite direction. Mainly, this means giving stereotypically “masculine” traits to the female protagonists such as independence, athleticism, and bravery. Sometimes, they go as far as making women reject men totally, or even reject their own femininity.

In many ways, this could be considered great progress. Males do not have a monopoly on traits historically (and often unfairly) associated with them, after all. Can’t a woman be independent, strong, assertive, and brave? Still, is encouraging women to be “masculine” rather than embracing their more “feminine” traits really a good influence on impressionable young viewers? Is this evolution really positive, or is it just another way to prevent self-acceptance?

The answer to this question is clear when movies with the most traditionally “masculine” princesses are looked at as a whole. While movies such as Mulan and Brave both feature protagonists who initially reject their femininity, this is an important part of their story-arcs that ultimately end with self-acceptance. If anything, they prove that a reconciliation of traditionally “masculine” and “feminine” sides, regardless of which is more prominent, lead to the strongest person.

Charming, or not so Charming?

To begin, it’s important to understand what Disney portrays as “masculinity”. As the first of a long line of movies in a similar vein, Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937) established many stereotypes – particularly in terms of gender – that became an important part of Disney movies for years to come. These stereotypes are ones that fit with traditional views of gender; men are portrayed as more powerful, decisive, aggressive, and heroic, while women are portrayed as passive people with very little to offer besides good looks, the ability to do housework, and a soft heart. In the early Disney movies, female characters have little to do with any significant change in their own stories. They may be the title characters, but they aren’t the heroes.

An interesting thing to note is that, for a movie that is often criticized by feminists for its less-than-empowering messages about women, Prince Charming himself has very little screen-time in Snow White. Admittedly, the movie is called Snow White, not Prince Charming, but this still raises the question of whether the film portrays men as unimportant. In addition, Prince Charming is flat and unchanging. Still, that could be argued for all characters in the movie, who seem to function solely as archetypes rather than real people. In fact, this archetypal characterization is exactly what makes Snow White such an ideal movie for study when it comes to gender ideology; Prince Charming’s limited scenes and flat characterization give a wealth of information about what it fundamentally meant to be a man in 1937.

The scene in which Snow White meets Prince Charming is the first encounter the viewer has with his character. When we first see Prince Charming, he is riding a white steed up to the castle. The background is brown, earthy, and unremarkable, which makes the lone figure of the prince stand out even more in his dark, royal blue clothes, bold red cape, and feathered cap. From this first image of him proudly riding his horse, the audience already knows several things about him; he’s bold, adventurous, and independent.

Then, all of these ideas are taken further. He hears a beautiful voice, and he follows his adventurous impulse; he is not afraid to break into someone’s home and check out this woman who has caught his interest. This is boldness that would be ridiculous today and probably end with a charge of breaking and entering, but, in this context, it is portrayed as a positive, heroic pursuit of his goal.

Perhaps the most disturbing thing, from a feminist point of view, is his pursuit of Snow White once he interrupts her singing. Snow White sings of hoping “for the one I love to find me”, yet her reaction when the prince appears is not one of recognition, but of fear. As a result, it is easy to conclude that Prince Charming and Snow White have never met before. Yes, he is polite enough to take off his hat and ask about Snow White’s feelings, like a gentleman. However, when she runs from him and slams the door in his face, he refuses to accept this rejection. He continues to harass her from the courtyard, moving closer and closer to the closed door as he sings. Worse, it portrays Snow White as secretly enjoying this pursuit.

From this, we can conclude several things about Disney’s views of men. A man must be bold and follow his instincts, regardless of the reactions of others. A man’s choice of mate can be solely based on shallow things such as the beauty of a woman’s voice and face, and constant harassment will win her over. In fact, that is a demonstration of his manly determination and drive.

The next significant scene for his character is when he “saves the day” by kissing Snow White. Again, this scene has some dark undertones; the prince is, after all, kissing an unconscious woman that he has met once. Still, it is portrayed as acceptable; he saves the day, and Snow White is happy to leave with him. Once again, the winning attributes of a man are clear; a man must protect the weak, be bold and independent, and work to get what he wants. Ultimately, this will make him a hero. Good dress sense and good looks are a plus!

One last notable thing about gender ideology in the film is the difference between Snow White and the Evil Queen. Snow White is portrayed as the perfect woman by traditional standards: hardworking, humble, beautiful, and innocent. The Evil Queen is a woman who singlehandedly has the power in her kingdom. She is portrayed as an evil witch, but her worst evil could be stepping outside of her gender role into a position of leadership. Snow White and the Seven Dwarves portrays the defeat of a woman outside of her gender role to protect a woman comfortably inside of her gender role, a feat ultimately accomplished by men.

Be a Man

If Snow White and the Seven Dwarves can be said to represent one side of the gender spectrum, Mulan (1998) represents the other. Here, we see a woman who is uncomfortable in her own skin, and who can’t find acceptance until she literally becomes a man. While Mulan is a strong character, she has to ultimately reject her “feminine” side entirely to find both self-affirmation and affirmation from others.

The song “Reflection” is the clearest demonstration of her rejection of her own femininity. Because she doesn’t fit the cookie-cutter definition of what a woman is, she rejects her identity entirely. She decides that being herself “would break [her] family’s heart”, and that she wasn’t meant to be “a perfect bride or a perfect daughter”. In the refrain, she even admits that her reflection is “someone I don’t know”. From these lyrics, we get that she is very lost when it comes to her definition of self, and she considers herself a failure for not fitting her society’s definition of what a female should be. Why doesn’t she fit these, though? It’s because of her “masculine” traits. She cares little about appearance, enjoys adventurous things like riding her horse, and is hopeless at “womanly” duties like pouring tea. Therefore, we see that her strength of character that comes with these traits makes it impossible to be accepted as a woman.

Her reasons for becoming a man are not due to her rejection of self, though, but rather for the noble cause of saving her father’s life. This is a clear example of the fearless – even reckless – protector-hero archetype from the Prince Charming days, and is yet another example of a traditionally “masculine” trait.

While she originally doesn’t fit in with the men of her military training camp, she eventually earns respect through hard work and the help of a male guidance figure in the form of her dragon, Mushu. However, what is she achieving through her hard work? She isn’t changing her quirkiness or clumsiness. Instead, she is earning respect through continuing to work for what she wants – much like Prince Charming when he meets Snow White and attempts to win her affections – and through her increased athleticism and militaristic skills. So, what does this continue to tell young viewers subliminally? Simply that to be accepted as a woman, you must take on traditionally “male” traits of perseverance and militaristic athleticism. However, whether or not this is a negative thing is debatable; women are typically taught to be submissive, and encouraging a move in the opposite direction could be an important move towards gender equality.

Mulan’s heroism against the huns continues to characterize her new “masculine” traits. Again, she takes “crazy” risks to slaughter almost the entirety of the Hun army through an avalanche. This causes her friends to dub her “the bravest of us all”. Once more, this acceptance is entirely through traditionally “male” traits: impulsiveness, rash bravery, and even violence. This is the height of her adoption of masculine traits: there are few things historically more manly than the warrior.

This all becomes inconsequential once she’s discovered to be a woman, though, proving that even male traits aren’t enough for her to be accepted by society at large; she must literally be a man to earn respect.

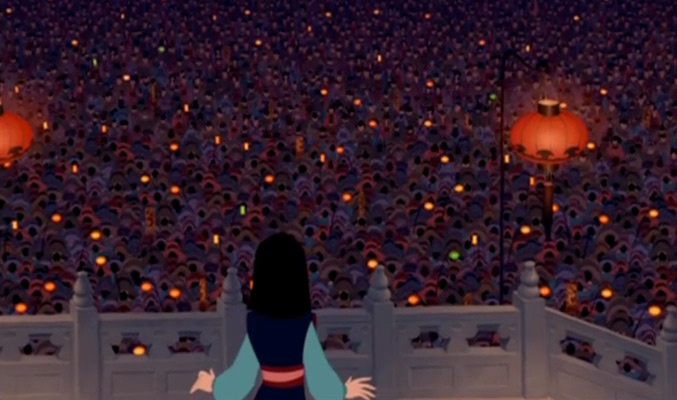

However, this damaging message is later contradicted when both Mulan’s male friends and the emperor learn to accept her gender. She is honoured in front of the ultimate authority in her country, in spite of her sex. In this way, she is given respect as she is… as a woman. She receives the acceptance from society that she desperately yearns for as a female hero, rather than a fake male one. The moral of this story is clear; being a real, if flawed, version of yourself is better than pretending to be someone else. Throughout the movie, we see Mulan try to be two false versions of herself: a stereotypical woman, and a man. The end result is that she becomes herself.

For this reason, in spite of its flaws, Mulan is a great role model for children. Yes, the protagonist has to become a man and take on “masculine” traits to receive respect, but she ultimately “blooms” as a woman. In addition, we see that Mulan doesn’t have to outwardly change to be accepted. She doesn’t need to give up her traditionally “masculine” traits; she’s still outgoing, adventurous, and assertive. Instead, she has to change inwardly by learning to accept that her “masculine” traits make her who she is: a strong woman who takes charge of her own fate.

The Disney Tomboy

Another case study of a “masculine” princess is the tomboyish Merida from Brave (2012). While she doesn’t “become” a man in the same way that Mulan does, she rejects traditional femininity to a far greater degree. She challenges all female stereotypes of the Snow White era; she is decisive, athletic, strong-willed, stubborn, uninterested in romance, and, of course, brave.

Frankly, Merida seems to hate being a woman and all it entails within her society. She notices the disparity between her parents’ treatment of her brothers and herself, claiming that “they can get away with murder” while she “can never get away with anything”. This injustice, and her unwillingness to accept it, already prove that she has assertiveness and insight that is unheard of by the early Disney princess.

Merida rejects suitors and is willing to risk war for her own happiness. She takes charge of her own life and doesn’t require a man to be happy or successful. She puts herself first, which is a potential parallel with Prince Charming from Snow White. After all, he is a prince, and Snow White’s stepmother is a queen. Isn’t opposing her, the central power of another kingdom, a risk? Either way, it’s easy to see that both Merida and Prince Charming go after what they want, regardless of consequences to themselves and others.

Her hobbies, in particular, demonstrate her similarity to the typical Disney prince. She loves to go on adventures with her horse, and archery is her passion. This is another show of her independence and adventurous spirit: her equivalent of Prince Charming climbing Snow White’s castle wall. More than that, her hobbies shows an acceptance of the warrior lifestyle that Mulan also lives. However, the difference between them is that Mulan becomes this ultimate male stereotype of the warrior for the necessity of protecting her family, not necessarily because of her rejection of womanhood. After all, while Mulan may not fit the typical woman in her society, she doesn’t seem to hate being a woman. Without the need to protect her father, would she have gone to war as a man? It’s doubtful. This sacrifice is also more typical of the traditional woman in the sense that she is putting others before herself. Merida is the opposite, taking up warrior pastimes by choice – purely “selfish” reasons, if you will – rather than because she’s backed into a corner. In fact, she openly admits that she doesn’t want to be a princess because her gender restricts her freedom.

This rejection of stereotypical femininity causes conflict between Merida and her mother. If Merida represents the rejection of femininity, Queen Elinor represents its embrace. This means that Merida’s rejection of her mother and her ideals can then be seen as a rejection of her own femininity.

If this is the case, Brave and Mulan actually have very similar plots. Throughout the film, Merida doesn’t lose the essential traits that make her who she is, but she comes to repair her relationship with Queen Elinor. While still respecting herself, she learns to also respect her mother’s femininity. This is about much more than a mother-daughter relationship; the entire film is a metaphor for Merida coming to terms with her own femininity… and with it, her whole self. Both Mulan and Merida, arguably the most “masculine” of the Disney princesses, are characters who make a journey of self-acceptance. Therefore, neither are movies that teach young women that a woman must be “masculine” to be strong. In fact, they teach the opposite!

A Happy Medium?

The examples so far have been extreme, but that’s not to say that there aren’t princesses in the middle of the feminine-masculine spectrum. In fact, there are a few that manage a very successful blend of “masculine” and “feminine” traits. In particular, the movies Pocahontas (1995) and Tangled (2010) offer strong female role-models that embrace their femininity while remaining strong characters with more to offer than beauty and obedience. Both Pocahontas and Rapunzel are the heroes of their own stories without having to reject their traditional gender identities.

Pocahontas embodies many typically “female” traits. She is beautiful and exotic to John Smith, which really starts their relationship. If she were less beautiful, would he have pursued her or listened to her views? Would they ever reach a new kind of cross-cultural understanding? Considering John’s initial attitude towards First Nations people, likely not. Physical beauty is certainly something that is important to her story, but, unlike the early Disney princess, she has much more to offer than good looks and housekeeping skills. Love and empathy guide her actions and are actually necessary for her heroism, even if they’re often considered weak “female” traits. Her acceptance of another culture, something that comes from her gentle spirit, allows her to risk everything to prevent a war. In addition, her unwillingness to single-mindedly pursue her desires without thinking of consequences – in the way that Prince Charming does – is an important part of her heroism. Prince Charming seemingly abandoned his kingdom to search for “love”. Pocahontas does exactly the opposite; she gives up the opportunity to be with the man she loves to act as a peacekeeper for her people and the Europeans. This sacrifice is courage to the extreme, but not something we would see from a character like Prince Charming. It’s a quieter kind of a courage, much different than battling dragons or breaking into the homes of Evil Queens. This is a woman’s courage rather than a man’s.

Her adventurous independence, assertiveness, determination, and courage are also essential parts of her, though. It is exactly the balance of traditional female and male traits that make her such a successful protagonist. She is flawed, complex, and self-affirming, and she does it without being a warrior or a tomboy. Pocahontas is a character who teaches young girls that you can be a hero while still being feminine, which is certainly a great improvement on the gender ideology portrayed in Snow White.

Rapunzel is a heroine who fights for what she wants, but, again, we see her embrace her typically female traits. She is kind, accomplished at “feminine” activities, innocent, indecisive at times, and, yes, beautiful. These are all important to her character, but don’t serve as weaknesses. Indeed, her empathy gets herself and others out of multiple scrapes throughout the movie, including befriending a tavern full of thugs and coaxing the good heart out of a wanted thief. Nevertheless, she is not a Snow White. She pursues what she wants without needing a man to save her. Her relationship with her lover is one of mutual respect rather than dependence. She is her own person, but she does it as a woman content with her gender identity.

The Verdict

Is this in-between princess better than complete rejection of “feminine” traits? Perhaps not. After all, Mulan and Merida need to reject their femininity first to enable them to embrace it later. They also show a different kind of woman than earlier Disney films or the in-between films like Pocahontas and Tangled, promoting acceptance of yourself regardless of how well you conform to society’s gender identities. In fact, the evolution of the Disney Princess may be helping to redefine the definition of “masculine” and “feminine” entirely. By portraying characters with varying degrees of traditional femininity and masculinity that are at ease within themselves and society, we can see that it is neither “feminine” nor “masculine” traits that truly give a man or a woman his or her gender.

With the current trend of Disney princesses, it’s possible to hope that future generations will not consider personality traits to be gendered at all. If this is the case, then the evolution of the Disney princess is truly a positive thing for youth of any gender.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Disney Princess keep getting more and more progressive to fit the mindset of the world .

An issue with Ariel is that she spends literally the entire movie and thus most of her life going to extreme measures to become something she’s not.

The Little Mermaid is sometimes referred to as a Trans woman’s story:

Ariel spend her entire life trying to become the person she knows she is inside, and would like her outside to reflect her inside.

Thats putting it very very simply, but ya – that is exactly what some people experience in transition.

I don’t think Mulan is really challenging any gender roles. She has to pretend to be a man.

That was my initial thought, but, after looking at the film more closely, I had to change my opinion. As I said in the article, she ultimately embraces her femininity; she just has to pretend to be a man first to reach a point where she can do that.

Yes, because she’s in a society where challenging gender roles is HARD. She doesn’t just waltz in say “I want to be a soldier, make the tests easier so I can pass.”. She actually _achieves_ what a recruit is supposed to achieve to become a solider. She Challenges gender roles _and beats them_. She doesn’t beg men to accept her, they accept her because she EARNS it. The gender roles are exposed as fake, artificial constructs that are at best guidelines.

Mulan is my forever favorite disney girl (she’s not a princess) then there is Belle (she become a princess because of marriage).

It is rather nice to see Disney *slowly* evolving to show stronger, more independent women. I’d love to see a transexual/transgender Princess — and I choose to believe that some day that will happen. I can’t wait!

This article was an enjoyable read, it was nice how you seemed to question everything’s values as potentially good and bad rather than side with any one trait being better than another.

Because of this evolution, I am very excited to see Moana, the first Polynesian princess. She is being voiced by a teenage Hawaiian native. Her quest is reportedly trying to find a fabled island. With the evolution of princesses, it will be interesting if the go the tomboy route as they did with Merida or the opposite with Rapunzel or Anna. Maybe they have even found a decent middle ground with her. We’ll find out in 2016.

This is really interesting to think about in light of why the typical princess plot has evolved. Society demands progressively more of its female characters and is looking for a romance dynamic that is more complex than Prince Charming saving the damsel in distress. This article is a good reflection of our changing values.

Disney as a whole is showing signs if evolving I think. Look at them portraying lesbian parents in an episode of Good Luck Charlie for example. That would never have happened years ago. This sort of evolution is important to remain culturally relevant and I’m glad that Disney is embracing it. Having strong role models from all walks of life is important for kids and Disney have a lot of power to do good there.

Great article, and I loved how you used three different princess to show a gradual change on how princesses are depicted picked thought the years. Mulan in particular shows how women were treated with less respect than men in that time in China’s history. Men were seen as fit to go to war while women were forced to stayed at home, and the film shows how this mindset was very biased.

I find Pochahontas errs on the side of racism a bit. The end where she goes off with the white guy, only to later conform to British society (in real life) used to make me feel quite uncomfortable as a child.

I completely agree with you. At its core, Pochahontas represents the fetishization of Native women. While I can see Laura Jones’ point that it does, to an extent, elevate traditionally feminine traits, it is ultimately a racist caricature. Pochahontas’s beauty emanates from her dark skin, and her allure from her foreign identity. Her connection to nature is not so much a pillar of strength as it is a co-opted ideation of Native peoples and their “inherent” connection to nature. Considering that Pochahontas’s feminine progress is wrapped up in racist expressionism, I don’t think one can conclude that it represents progress, but rather further permits the widespread tendency of Western cultures to fetishize Native peoples.

I think that this article is pretty interesting and a fun and intriguing read.

Feminism should mean that all women has the opportunities that men have, which also means that if you fall in love and you want to be with that person over anything else, you should be able to do it.

I agree with your last statement, but society likes to distort this message by declaring every choice a woman makes automatically empowers her. Ariel made foolish decisions to abandon her family, friends, and entire world for an attractive stranger, but she did so as a teenager, not a woman.

Speaking as a man, my mom won’t stop talking about when I dressed up as Mulan for Halloween.

Sounds like a mise en abyme.

Belle deserves a little more credit. After all, she’s the Disney princess who complains about her “dull, provincial” hometown and is totally unmoved by Gaston, who, let’s face it, is a hottie.

Great feature – I love these films.

I love that Brave depicted a strong and heroic woman (women really, since the mother was also quite a strong woman), but I have to say as I look back on Disney movies I realize that there is no true partnership. The men in Brave are goofy at best, incompetent at worst. Even the father, who is seen as a “good man,” needs the mother to keep him in line, to show him how to be an effective leader, to keep him as more than a drunk buffoon. Simply another stereotype of marriage. When will we have a meaningful and egalitarian relationship for our young boys and girls to look at?? We need to show them what it means to be a team- not rescuing, overshadowing, or keeping in line.

I really appreciate how you distinguish between princess stories where the protagonist is stereotypically feminine (Snow White), stereotypically masculine (Mulan or Merida), or a more nuanced picture of femininity (Pocahontas or Rapunzel). It definitely lines up with a lot of my thinking that the right way to do something is usually between two extremes. I would argue that the portrayal of Rapunzel (and also Belle, my favorite Disney princess) displays a lot of the positive, correct qualities associated with traditional womanhood – being protective, listening, self-sacrificial, and nurturing – without weakening her, denying her agency, or making her stereotypically masculine. Given the extent to which stories shape us, it is crucial to evaluate what we tell our children about what it means to be a proper woman, whether in today’s world or in fantasy.

Very interesting and well written article. I really like the idea of using Disney movies as a gauge for society’s progressiveness.

Great article Laura. I especially love your concluding statement “it’s possible to hope that future generations will not consider personality traits to be gendered at all”

What a thoughtful and sensitive analysis! You have selected the appropriate examples for your ideas.

Esmerelda and Jasmine are my personal favorites. Jasmine, for being a princess who wants to have “normal” freedoms and her pet tiger. Esmerelda for her fight for her Roma people, her dialogue for sparring with the male characters and for her resourcefulness. She does get saved by Phoebus in the end but it is a very gratifying conclusion and only after she saves him first. I love the line where Phoebus compliments Esmerelda for “fighting almost as well as a man” and she responds by saying she was going to compliment him by saying he “fights almost as well as a man.” Calling him out on his chauvinism. Definitely a Disney first.

I like the gender identity exploration on what it means to be a woman. Stereotypical or modern: every woman goes through a period of questioning who she is and how comfortable she is in playing the roles society assigns her. I hope that we get a wide variety of answers to this question because eventually it would be nice to feel that each individual unique woman can self-determine her acceptance of herself and find her place in her worlds. As audiences embrace more complex characters, Disney will keep providing them for us.

I think the first thing that needs to be understood is that “femininity” and “masculinity” are societal concepts, which you kind of touched upon. So by rejecting their “femininity” they are actually just rejecting the societal norms and expectations for women at the time NOT their gender or even their womanhood and they are thus not adopting “masculine traits” but behaviors/actors that were identified with men by society at the time.

I think also it would be interesting to look at the difference between the original Grimm’s tales and the disney adaptions in terms of gender roles (I wrote a paper about it and there’s a lot of published work about the topic), where you can see more of how male characters like Prince Charming and the dwarves are given a much larger role in the disney versions and how that is problematic for women.

I am really enjoying all the discussion on this article. Who would have thought that talking about Disney Princesses could lead to such intriguing discussions about the nature of men and women; male and female roles in society; and what is or isn’t ‘feminist’.

Love Brave. Female heroin, sidekick, and villain….

If we are to make Disney movies more gender aware, we cannot disregard the importance of representation of masculine characters.

Definitely not. Adding that in would have made this horribly long, but I agree that it’s a concerning related topic.

I was thinking about that while I was reading this. There aren’t many Disney movies centered around actual men (rather than anthropomorphized male animals). Aladdin is the biggest one, but I’m not sure how I feel about that as a representation of masculinity. There’s Tarzan, but his is more of a story about human vs animal nature. The only other ones I can think of are Atlantis and Treasure Planet, which, admittedly, I haven’t seen in a long time and which don’t get much recognition. And that’s a shame because when I was a kid I connected with Milo from Atlantis as the “nerdy” intellectual. Most of the other Disney men act as the object of the woman’s desire (a la Charming and the other princes) or as the antagonist (Gaston). There are plenty of young boys out there who like Disney movies (I was one of them) and who deserve a positive male representation, but I feel like they aren’t being targeted enough.

This is very helpful formy research, so thanks!

I believe that the evolution of Disney princesses to show more strength and willpower is astonishing, and will help the younger generation of Disney princess lovers to develop a deeper personality.

I love the detail in this article, and the grouping of Disney princesses based on gender expression is a really clean way to pinpoint the societal trends that accompany the films.

Also, sidebar: did anybody else pick up on the fact that Rapunzel’s weapon of choice is a frying pan, an item that belongs in the kitchen–a traditionally feminized space? I thought it was rad to see a cultural symbol recontextualized like that.

I feel incredibly stupid for not picking up on that and putting it in! Great insight.

This was such a very interesting and eye-opening article in regards to how the makers of Disney often define our own interpretations of masculinity and femininity. Disney has a lot of power to influence even the youngest of children, and I think that it is really important that parents and movie watchers understand this.

Mulan makes some strides, but she has to pretend to be a man

I actually addressed that point in the article. Someone else above in the comments had something quite insightful to say about that too.

I don’t believe that Merida hates being a woman so much as she hates the role she is being forced into by the established societal role that women are supposed to hold. In her purview, men are given free reign to do as they wish, pursue what they want, be who they want. Her freedom to explore her own identity was curtailed as she approached adulthood. The attitude that she has personifies the male paradigm, the ability to decide her own destiny.

It becomes established that Merida idolizes her father, and tries to emulate him. That isn’t to say that she fails to recognize the power that her mother wields on the other hand. Her mother stands as an authority in her own right. Merida only rejects her mother’s configuration of who she is supposed to be because Elanor and Merida were born from different molds, and can’t reconcile their separate configuration. They fit differently to each other because the part of the picture that they try to fit the other one into doesn’t fit. It is only until the end do they realize that their best method is compromise, so that their opposing edges don’t clash, but complement.

Thanks for opening up this discourse beyond simply the great Princess debate!

I actually think Frozen does a fair bit of gender bending, a contrast to Disney’s past portrayal of female protagonists in their normal gender roles. This ultimately leads to the feeling of empowerment in the female audience as they are lead away from the normal gender traits. This is the reason why I believe it has become so popular with female audiences; it gives them a sense of empowerment.

I completely agree!

I largely appreciate the arguments you lay out in this article and the discussion you’re generating. The examples you use are all effective, and of course it was rational not to analyze every princess because that would take forever.

However, I protest your reference to a “man’s courage” and a “woman’s courage.” I believe there are many movies, including Disney ones, which depict men displaying a bravery that involves preserving the interest of others, rather than himself. Tarzan would be a prime example. He is negotiating the meeting of two worlds, just as Pocahontas does. To claim that selfish courage is “masculine bravery” seems equally unfair, as you point out that many females like Merida (and Ariel, Jasmine, and arguably even Tiana) demonstrate a self-motivated courage that disregards consequence to others.

Definitely; that’s a great point. I agree that there is no such thing as a man’s courage and a woman’s courage in reality. However, I was going by traditional stereotypes of masculinity and femininity. Historically, women weren’t supposed to be selfish! That just goes to show how damaging traditional stereotyping is to both genders.

Ah! Of course! That probably should have been apparent to me, given the context and framing of the article as a whole.

That is definitely what I want to see. Feminine princesses, masculine ones, in between. Basically who you are is who you are in any combination of traits.

The rejection femininity is a very human reality, men and women both reject feminine traits as they don’t want to be seen as “weak”. This takes place in these narratives because it’s a real and pressing feminist issue.

Does making movies more femnist mean we have to erase all gender stereotyped people, like they never existed?

This was a good read. I liked your analysis of the Disney princesses and the gender roles of their time period as well as the other arguments you make.

This was a great read. You really balanced the arguements, especially since you took into consideration the historic periods. It be great to see a genderless prince/princess one day, or maybe one of a sexuality that is not heterosexual to really witness the evolution. While you talk a lot about the masculine/feminine spectrum of the main characters, I think it would be interesting to look at secondary charachters, and where they fall on the spectrum and how they influence the princesses and their audiences. Two that come to mind are Simon and Pumba, since they are both males but raise Simba in ways that can be compared to the Fairy God Mother archetype.

Nice article. I currently teach in a middle school and I think this can be handy.

Though you do make a fair point on Merida and Mulan, I’ve never thought of these two rejecting femininity entirely. Yes Mulan has too literally become a man, but throughout the movie we see her kindness and empathy show through and this kind of sensitivity is not seen with her fellow warriors; in fact it nearly gives her away. As for Merida, gender really isn’t the issue at hand in the movie. Yes she doesn’t display the traditional “feminine” qualities we usually see from Disney princesses, but that isn’t the point. I believe she simply rejects royal life for it’s demanding responsibilities and expectations in general rather than those only set on women. You do make an argument about her brothers sharing none of these responsibilities, but they are obviously extremely young, while Merida is obviously in her teens. Feminine stereotypes may have been a real issue in the past, but I wouldn’t say these two movies went to the extreme to contradict those stereotypes.

I find storywriters who “break” away from the gender stereotypes go further in their stories, creating something brilliant and relatable to people in real life. Every person has more than one trait to their personality, so why not be realistic and show that within the characters? It’s important for children to see that every individual holds different traits. Creating a Disney movie showing a male or female “stuck” within their stereotype will fail these days.

I love how balanced your arguments are here. I truly believe that some people blow the Disney Princesses way out of proportion. I completely agree with the way you view Rapunzel and Pocahontas. As a female myself, I have a balance between the masculine and feminine. I sometimes think people are saying that it is wrong to be feminine, but what if that’s who you are? That doesn’t make you weaker, or more emotional, it’s just you being you. But I understand that there are more sides to the coin, and I think this article brings to light the various ways one can look at a Disney Princess. I personally believe that women can be both feminine and masculine, and not be defined by the stereotypes that I believe Disney has come a long way from portraying.

I love this comment! I especially love how you pointed out that it’s not wrong to be traditionally feminine (or masculine) if “that’s who you are”. I love most of my more traditionally “feminine” traits, and I wouldn’t trade them for the world (I wouldn’t trade my “masculine” ones either).

Really interesting! Great article! It really made me think

This was a great article, and it really got me thinking as well, as many readers have already voiced. I always loved the representation of villains in Disney films as much as the princesses, and in many ways they seem quite empowered or sexually confident in themselves, yet by the sheer nature that they are a villain, they often suffer within that narrative. It is almost as if a more progressive or inclusive form of femininity exists but it is still bordered in. I would be super interested in seeing how the representation of female villains has also shifted to accommodate public viewpoints, even if they may still be problematically represented.

This is a really interesting topic, especially in the current time we all live in, having tracked disney from as early as Snow White from not the 30’s but our own childhoods. This compressed view through the years and up through the Disney movies is facinating to look at, and you convey this well. I think something equally as interesting to delve into would be an analysis of if we feel we are entering a modern trend of such boundary knocking- down that the architypes for story telling would be rendered outdated, or would be too “offensive” (i.e. no woman can ever be needing assistance, or no villan can be depicted as ugly). Your article really got be thinking! Thanks!

I cannot say that this is a good representation of the gender spectrum, especially when, in Mulan’s case, it is not that she wants to be a man it is that she want to be accepted. One has to remember the time at which each movie came out and the concepts in society at the time. Heck, Snow White came out before Simone de Beauvoir’s “The Second Sex,” so, at that time, we had no feminine ideology to challenge these ideas. What we see in Mulan, is her character traits being in a category probably farther than “the other.” Normally we take the category of “the Other” to be anything not male, not the key gender. So, when we see Mulan, we see that her character traits are even different than what women accept. Also, in the case with Mulan, we don’t see how she was brought up with these ideas about how to act. As Judith Butler puts it, our gender roles are learned. It might be a coincidence that Mulan came out 8 years after Judith Butler’s book “Gender Trouble.” All in all, the feminist aspect of this article is a little of with a defined idea of what gender is and categorized. In the first two examples it really sounded as if everything was a dichotomy and not a spectrum.

Interesting!

I liked how you brought up that Disney princesses over generations have had to learn to balance between “femininity” and “masculinity” to be their best self. Modern Disney princesses in this way are so similar to today’s women. However, I hope that as time passes, traits are no longer denoted as “more feminine” or “more masculine”- instead women should simply choose the traits or lifestyle that allows them to be their best self. In any matter, it should be celebrated that Disney princesses are increasingly representative of the strong, successful women of our society. Thanks for the good read!

This is a really interesting.

For the 1st time in Mulan and Tangled, the women were portrayed as having some masculinity not the stereotypical lady of the 18th and 19th century.

It is always very interesting to me, as someone who loves Disney and who grew up on it, to look back and reflect on the (more often that not) hazardous representations of women in Disney films, and how they’re more progressive as the years go on because we are becoming increasingly aware of how poorly women are portrayed in media. With the addition of Merida, and now Moana, there is a much more conscious effort to have the female protagonist be assertive, adventurous, and successful without the help of a knight in shining armor. It is surreal to look back onto old princesses and see what was considered the height of diversity, even if they do portray women as masculine=good, and paint a picture of femininity=bad, that is quite undesirable. I hope that as the years go on, and media continues to listen to society, women in Disney films won’t have to sacrifice their femininity to be heroes.

There have been a number of academics who have looked at the Disney princesses as well over the years. In addition to the princesses becoming more gender-neutral in their interests, the princes have also decreased in the “traditional” roles of “active” embodying the action in the films. Disney has also seen a change towards a unified queen away from divided female characters pitted against one another.

I thought this was an interesting take on the progression of “masculine” qualities in Disney princesses over time. Specifically in regards to Mulan, I thought the point that pretending to be a man is what helped lead her to accept her womanhood more was very insightful. However you used the example of Mulan’s plan to bury the Huns in the avalanche as an example of her “masculine” traits of recklessness and bravery when it was the exact opposite. Although the fight did get her termed “the bravest of them all” by her fellow soldiers, it was actually a very calculated move that exemplified one of Mulan’s more underrated traits, her cleverness and knack for strategy. Mulan realized the one remaining missile wouldn’t do significant damage to Shan Yu’s army, so she ignored all the people yelling and shot it towards the mountain and burying the thousands in the rapidly approaching horde. All though the most obvious example, Mulan’s cleverness is what actually caused her to succeed in the situations her bravery put her in and it’s on display from the very beginning of the movie. When she’s late to get ready for the matchmaker she rigs a device so her dog can feed the chickens, while being dragged through her makeover she stops, analyzes, and wins a chess game between to older men sitting in the street, and finally figures out how to use the two weights to climb the pole in the training camp and retrieve the arrow. Had she not been able to think creatively,her bravery would’ve been for little since she would have been sent home during training. Although intelligence is obviously not gendered, there’s still the implication that being female is what lead her to think around problems differently than all the other characters. While the other soldiers, and especially Shang, try to solve problems in a very direct and more “masculine” fashion, Mulan considers every possible angle. When Shan Yu makes it into the Emperor’s mansion, the soldiers attempt to make a battering ram which proves mostly ineffective. In a fairly obvious metaphor, simply hitting the problem didn’t solve it. Instead Mulan, the lone female, thinks of using the columns around the house to gain access. The more “feminine” trait of flexibility leads to her greater success as a strategist. Mulan for a long time was the pinnacle of the “masculine princess” yet it’s her feminine traits that save her live throughout the film and lead to her eventual victory.

Kudos on a thorough article that examines not only extreme versions of masculinity and femininity, but examines the “happy medium,” too. I’m with you; we need more “medium” princesses. I’m not sure which is worse–the uber-feminine princess who is totally dependent on men, or the princess who is only taken seriously after embracing or honing masculine traits. It is my personal hope that Disney will continue creating female protagonists–not necessarily princesses–who are more balanced than Snow White or Mulan.