Memory in Film: Mementos and Maneuvering Through the Past

Memory is both a powerful and unreliable narrative tool in storytelling. People use memories to prepare themselves for certain situations, to reflect on their own growth, or to reminisce about past significant events, even if the memories themselves are unreliable. Nevertheless, they can bring out intense emotion, and cinema has ambitiously utilized memory in the hopes of evoking that desired reaction of nostalgia or regret. The 21st century in particular has seen a rising interest in the science and understanding of memory, be it due to the exponential presence of the internet and development of technology or new findings in cognitive function research. Although movies continue to use traditional methods of memory-based storytelling, other films have challenged the age-long formula of exposition to challenge an audience that has greater access to recollective triggers, like digital photos and videos.

Learning From the Main Character

Flashback is a technique that has been used in some of the greatest films of all time, and so it is one of the most popular methods of using memory to structure a narrative. From 20th century classics such as Citizen Kane and Forrest Gump to more recent well-acclaimed pictures like Slumdog Millionaire and The Grand Budapest Hotel, this narrative formula has been prevalent in some of the most popular films for roughly a century: the present is unknown, making the audience confused and curious, and a reliable narrator, often times the protagonist, guides them through the past. While there may not often be a suspense factor, it still makes the viewer wonder how the vast differences between the memories and the present could be connected.

Danny Boyle’s 2008 Slumdog Millionaire violently begins with the protagonist Jamal being detained and tortured amidst accusations of cheating on the game show Who Wants to be a Millionaire. From the dull and uninspiring setting of the police station, Jamal takes the two officers down a colorful yet painful childhood that coincidentally, or prophetically, gave him the answers to nearly all the questions thrown at him.

The climax of the narrative begins when Jamal no longer has the past to rely upon; he fearlessly takes the chance because he’s secured what matters most to him, his friend and love interest Latika. Jamal is seen as a genuinely good person, and so the audience both believes him and cheers for him. The end.

Now, in the case of Slumdog Millionaire and several other movies using flashbacks, Jamal is a reliable narrator; he’s of sound mind and an honest person. Now, what happens if the narrator isn’t one or either of those things? The 2017 film adaptation of the play Marjorie Prime subverts these expectations through its narration and visualization of memories. Unlike most flashback movies where the past is presented with absolute precision, Marjorie Prime is very dialogue-heavy and the audience is forced to imagine what the past looked like whenever any of the characters describe it. It’s both a challenge and a reality check as to what memories really are, as demonstrated by a conversation between Marjorie’s daughter Tess and her husband John.

John: “Memory. Sedimentary layers in the brain. You dig in. You know it’s there you just have to…”

Tess: “No, no. I thought you knew the basic idea, according to William James.”

John: “Maybe, once, long ago.”

Tess: “William James had the idea… that memory is not like a well that you dip into or a filing cabinet. When you remember something, you remember the memory. You remember the last time you remembered it. Not the source, the source is always getting fuzzier, like a photocopy of a photocopy… So even a very strong memory can be unreliable because it’s always in the process of dissolving.”

With Marjorie suffering from Alzheimer’s and Tess having a very complicated relationship with her mother, John is seen as the most reliable narrator, yet he never experienced the memories that the latter two did. No matter how hard he tries, he’ll always be outside looking in. The anchors of the narrative end up being two flashbacks shown of a younger Walter and Marjorie. Not only do they give the audience “secret” information that reaffirms their suspicions of the narrators, but they also solidify the motif that memories exist outside of the characters’ world: they’re unreachable, gradually fading away from those who were part of those moments. It’s not an issue of an unreliable narrator; it’s an issue of a realistic one.

Watching the Main Characters Learn Memory

Many great works in cinema have revolved around memory loss. From action thrillers such as the Bourne series to adventure comedies like The Hangover, amnesia is what drives the plot, as the characters often race to find out what has put them in their situation before outside forces interfere. In the few cases where the main character can remember something, it’s always immediately preceding the climax of the film, usually a moment of clarity amidst the chaos. This is unlike flashback movies, where the narrator is often speaking from the conclusion of the story, confidently reminiscing on the memories that dominate screen time. In memory-loss movies, there is no narrator that reassures the audience when and where a past event takes place. The viewer is just as lost as the protagonist.

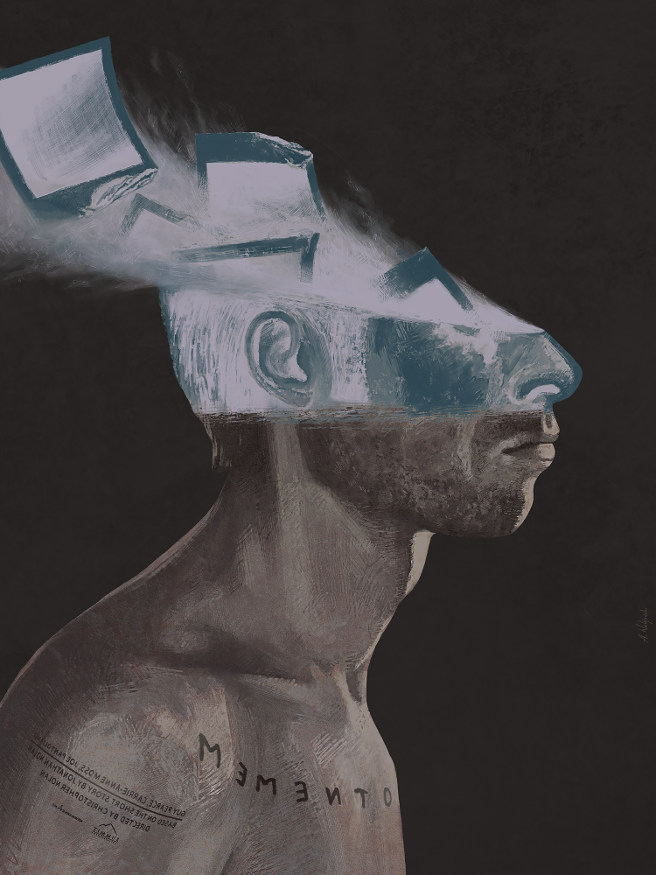

There are several forms of amnesia, but movies generally stick to retrograde amnesia, amnesia pertaining to an incident or time in the distant past. This has the film move in one direction in its chronology: back. The goal is to collect lost memories and put the pieces together. It’s pretty much a treasure hunt, where the hero needs to know enough to avoid the bad guys and then know how to beat them. What very few stories have dared to incorporate into a narrative, however, is anterograde amnesia, the inability to create new memories. Because it’s an issue of memory retention, it’s no longer a simple treasure hunt. It would be as if the hero were to know where the treasure is, sail there, pass out, and then wake up the next day to find out the treasure is at some other completely random location. In order to not frustrate the audience and keep the plot going, there would need to be clues or bookmarks that can help everyone move forward and discover new information. That’s where Christopher Nolan’s Memento comes in.

Memento, one of the most critically acclaimed films of the 2000s, exceptionally manages to demonstrate the condition’s detriment on protagonist Leonard’s life while also progressing the plot, and it manages to do it so well with the use of two separate but connected narratives: one being an “objective” view of Leonard summarizing his situation to someone on the phone and the other being a reverse-chronological series of events from Leonard’s perspective. With those scenes, the audience learns the meanings of his tattoos and Polaroids, gradually revealing the situation Leonard sees himself in.

Because he can never retain the new memories he makes, Leonard makes the viewer wait for him to catch up, now anticipating when he can connect the pieces. Leonard is not a reliable narrator, and the characters that interact with him are not reliable either. His condition makes him prone to misinformation and manipulation, so can the audience even trust that they’re connecting the right pieces as well?

While never receiving the same degree of fanfare as Nolan’s later movies, Memento redefined how amnesia and memory manipulation could drive a narrative. Several films have attempted to capture the same suspense and intrigue Memento had, such as the 2013 movie Before I Go To Sleep. Like any type of iteration, however, it fails to deliver a fresh take on the premise. The protagonist Christine, like Leonard, has anterograde amnesia and uses mementos (no pun intended) such as photographs to keep track of what she knows.

The plot is more intimate and unsettling and the narrative structure isn’t identical to Memento’s, yet it still feels as if it were a shallow rendition. The photographs Christine uses are never very important, as she seems to gradually regain her memories out of nowhere. The doctor that helps her warns Christine her memories may be confabulated, but, unlike Leonard who is blatantly being lied to by various characters, she seems to always subconsciously know the actual truth. It isn’t revealed that the film starts in media res until the end of the first act, yet the rest of the movie carries on as if Christine were simply starting to remember from scratch by retaining small tidbits rather than through the tedious and inevitably futile routine that Leonard needed in Memento. Ultimately, the issue with Before I Go To Sleep comes down to the fact that the audience never has to really worry that Christine cannot trust herself. With that, there’s no thrill and no reason to sympathize with her character.

Experiencing the Memory With the Main Character

Whether the narrator has a photographic memory or is an amnesiac, there’s always the slightest sense of uncertainty as to whether or not the past is being presented objectively. Science fiction had an unrealistic, yet concrete solution to that dilemma: time travel. Time travel has fascinated moviegoers for decades, with classics such as Planet of the Apes and Back To the Future entertaining the possibility of looking into the distant past or future, changing the course of history or preventing the soon-to-be. Although some movies do show characters looking back at moments in their past and reflecting on them, they aren’t the driving point of these films nor do they necessarily shape the narrative. Most of the time, it’s simply a change of setting. So what makes the narrative revolve around memory instead of just using the past as a change of scenery? Memory plays a hand because the protagonist and others involved in the time traveling often end up in the same position as the audience: expectant but also puzzled once things end up defying those expectations.

This is where Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind stands out. There are countless other movies that have explored characters witnessing their own past selves and decisions, but Michael Gondry’s 2004 film keeps the “time-travel” very intimate and personal. The movie begins showing the beginning and ending of Joel and Clementine’s relationship. Once Joel decides to erase Clementine from his mind via a memory erasure firm, he—along with the viewer—re-lives all his memories of her. Unlike exposition where the narrator is reliable enough to visualize and describe memories, Eternal Sunshine’s protagonist is just as fascinated and curious as the audience is of his relationship.

Joel clearly didn’t forget those memories; he only saw them differently once he took time to reflect on his and Clementine’s relationship. They both ask the same question: where did it go wrong? Despite the memories being assembled into physical constructions from Joel’s mind, the film masterfully keeps in touch with the emotional residue that certain memories, particularly those from relationships, can leave behind.

Similar sentiments to the appeal of relishing past moments in life are fleshed out in the Black Mirror episode “The Entire History of You.” The grain implants that can record and store memories in extreme detail allow the protagonist Liam to analyze meetings and interviews and prepare himself for any kind of social interaction. Once the audience is aware of what the technology provides and what it’s capable of, the problem is introduced: Liam believes his wife Ffi is being unfaithful, but he does not have explicit proof in his stored memories to give himself a definite answer. The rest of the episode has Liam finding out through other people’s memories, by extreme matters at certain points, whether he is right or wrong about his wife’s fidelity, and ultimately, the grain becomes a hindrance rather than a tool.

Although it never dives fully into the memories and the audience sees them from Liam’s eyes or a screen, it is a degree of immersion that closely resembles looking through old photos and videos on a cellphone. While the grain does not exist, people today have greater accessibility to browse through old pictures and videos and reminisce. This, like the episode shows, can keep people feeling stuck, paranoid, and ultimately crippled by technology that can do so much good in so many other ways. Memories are no longer as easily distorted within the mind; the photo/video itself takes care of that. It’s more than just a cautionary tale on the consequences of knowing things one shouldn’t; it’s an acknowledgement of technology’s impact in intensifying that consequence.

A Look Ahead Into The… Past?

Memories are intangible; people may keep records or tokens, but they never encapsulate the time or place of remembrance. The farther away the memory becomes, the less realistic and more extravagant it looks, as if it were simply a dream. Some filmmakers and storytellers embrace this and solely refine the idea, but others have challenged this perception. Science fiction in particular has recently taken memory as something that can be documented, stored, and manipulated to the minute detail, and it’s partly due to modern technology that is capable of recording. Despite the experimentation on narrative structure in the genre, there hasn’t been a film that has pushed the boundaries of memory/time-based narrative such as Denis Villenneuve’s Arrival.

Although it is a film mostly centered around the concept of language and communication, Arrival pushes the bounds in which memories can be interacted by, and it’s possible through the aliens’ perception of time: being another dimension that can be traversed, like physically moving from one place to another. It’s being able to see into the future, yes, but the film takes it to a much more intimate and personal level. It asks the viewer one question: if you knew that beautiful and happy memories would end in tragedy, would you still make the same decisions? Rather than reliving or relearning memories, the challenge is a matter of sacrificing for the sake of good memories. No matter what new tricks filmmakers and storytellers come up with, the real story lies within the personal and intimate truth as to what memories are.

Memory is a very complicated thing. It can be so stimulating yet so unreliable, and it’s hard to wrestle with the idea that things known or felt could be far from the truth or even outright fabricated. Regardless, memory-driven movies pull for emotion, for the audience to long or reminisce on the past. From Citizen Kane to Marjorie Prime, the emotional response that memories evoke has never changed. Even when movies deal with something as unrealistic as time travel, the audience can’t help but wish. Modern technology has allowed people to record as many memories as they desire, but nothing to this point can capture the feeling of remembering significant moments or events in life. It’s a universal sentiment, and good storytellers will always place that over any form of memory manipulation.

Works Cited

Cherney, Kristeen. “Anterograde Amnesia: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatments.” Healthline, Healthline Media, 29 Sept. 2017, www.healthline.com/health/amnesia/anterograde-amnesia.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Flashback.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 13 Aug. 2020, www.britannica.com/art/flashback.

Osborn, Corinne O’Keefe. “Retrograde Amnesia: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment.” Healthline, Healthline Media, 16 Oct. 2017, www.healthline.com/health/retrograde-amnesia.

Wiggins, Amanda, and Jessica L Bunin. “Confabulation.” StatPearls [Internet]., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 16 Aug. 2020, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536961/.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Nolan is such a fascinating filmmaker! I love how the manipulation of time has always been such an important element of his stories, no matter the genre; from Following and Memento all the way to Interstellar and even Dunkirk, he always pulls off doing something inventive.

I have been struggling with depression for a decade, and I’m not ashamed to say Jim Carrey is one of the people who helps me when I’m down. He may not be the funniest, or the best actor or whatever, but that spark that he has, the way his eyes light up when he’s performing or being interviewed, his confidence and ability to switch from bipolar comedy to sarcastic preaching and self depreciation – I love it. Same applies to the late great Robin Williams.

Yes Carrey and Williams are cut from similar cloth.

A lot of hate directed towards Eternal Sunshine, Human Nature, and everything in between and beyond. Nothing is perfect. But Carrey can act without a doubt; he is a professional, regardless of the repertoire.

It is a long time, that I watched Carrey in any film. Why? Because I couldn‘t stand it. It always felt as if the mask would fall in the next second and he would cry the very next moment. Like in those cheesy tales/stereotypes about sad clowns. There was this dark, bottomless sadness behind every joke, every grimace and movie and I felt ashamed witnessing it. What I saw was a desperate, driven man, not a man enjoying what he does.

These days he sounds way more happy and real and I hope this really is the case.

Memento is a modern masterpiece.

Part of the attraction of watching Memento was that, if you had had no warning, figuring out what was going on with the film was half the fun. The moment when you realized the key to unlocking the B/W scenes versus the colour scenes; starting the film with the death and then trying to unravel whether Guy Pearce had gotten his man; trying to determine whether Carrie Moss was a good woman or a bad woman; wondering whether his notes were going to make sense; wondering if we were ever going to hear the story of the man whose name was written on his wrist, and whose story was similar to Pearce’s. These were just some of the puzzles that required a viewer (especially for the first time) to hang in there, stay patient, and let the director and his writer brother let us in to the story. These were part of the components that made Memento magic.

The second time you watched it, preferably with a DVD that you could stop and start as you and your partner sat on the couch and debated where the tells were, how you missed it the first time, how it was all fitting together. And then, insisting that friends had to sit and watch it with you and watching them watching it for the first time and wishing that you could be in their shoes.

I don’t understand how that can be replicated in a remake though. Now that anyone who goes to see the remake out of morbid curiosity to see what they’ve done to the film is going to know all the secrets–where’s the fun in that? And for the audience who are seeing it for the first time, and thinking that it’s great and you’ll just want to say to them, “Wait. You have to see the original.

I think there are plenty of crappy films that someone could attempt to redeem with a remake. Think of all the great books that were turned into sub-par films. Why not start there? If you have good material but bad execution, fix that. Stay away from a film that worked the first time.

Besides, I don’t want to sit in a cinema full of youngsters who keep yelling at the screen, “Why aren’t you taking a selfie and posting it to Facebook? Why aren’t you checking your Twitter feed? All the answers are there!” The film won’t fly with those who have smart phones attached to their palms. They won’t understand that not too long ago, we had to wait to have things revealed.

I totally agree with your first paragraph, but what makes Memento a classic and easily Nolan’s best film is that it explores so many areas and ideas of humans. Perception of Identity, how memory works, the fallibility of memory, peoples manipulation of their own memory and how people perceive the world through their mind. I have seen it maybe 3 times and it is just as good every time. Plenty of reviewers (Ebert for example) seem to think that once you take away the backwards narrative technique the film has little else to it. Which I find laughable.

Inception or Interstellar have non-stop exposition that on a second viewing is dull and pointless but gives the audience a nice simple bow-wrapped answer to the entire film. Memento does not answer certain key questions but leaves them up for interpretation. We have an unreliable narrator and the audience is left wondering what is the true extent of Leonard’s condition or how much has he/others manipulated his memory. The best example is in the final scene when driving in his car Leonard has a flashback where you see a part of his chest, which is empty in the rest of the movie, covered with a tattoo that says “I’ve Done it”. Does he get tattoo removal so he can continue his spree and this is the reason for the flashback, or is Teddy his last murder and this flashback just a made up in his mind ? We don’t know?

I agree with you. I didn’t go into the various meanings attached to objects and to human beings, but yes, definitely, this is a film that has things to say about the human condition as I understand it to be.

And, as to the tattoo at the end, my partner and I have been so inspired (in a negative way) by the announcement that the film is going to be remade, that we have scheduled ourselves to watch the film again tonight. One more opportunity to see if we can figure out the larger existential questions that have, so far, eluded us.

Loads of people haven’t seen and it the main cinema going public ie 16-24 year olds were watching teletubbies when it was popular.

I know nothing about Marjorie Prime, beyond the fact that my mother would love to live with such a Prime of her late husband, with a simulcrum of his personality & memory. However, the film is wrong in that I suspect she would prefer the Prime to be as much nearer her own age, no reason I can see why this could not be done? Of course the Prime may be 40ish, because that was when he died, that would be logical. The Prime is a learning computer programme, listening to & watching a living person & so learning to perfectly mimic them in every respect, that might take decades to do, but if the living person died, the Prime would be `frozen` at that instant.

This is a poor, shallow film that doesn’t explode it’s ideas enough and wastes a very good cast.

There is so much more that could have been gone with this film, I found it half-formed, and unfinished. It’s a short story dragged out with some seriously slow pacing.

It’s a great idea but didn’t completely hold my attention on screen.

I watched Memento for the first time when I was immersed in neuroscience during my degree, and I was stunned at how accurate it is. A screening of the film at the Cambridge Science Festival a few years back was accompanied by a talk from Tim Bussey, a memory expert at Cambridge, and he pointed out a plethora of subtle references in the film to the case of H.M. that demonstrate how thoroughly it was researched.

What is so brilliant about the film though is the way accurate science was used to build such a powerful story – it really gets at huge concepts like the nature of memory and the mind and tells a compelling human story in a really original way. I think for it’s layers of complexity, it has to be one of the greatest films ever made.

I saw a really good movie about memory but I forgot what it was called.

I recommend Faith Healer by Brian Friel. This is a wonderful scramble around the recesses of memories and interpretations (or ‘reconstuctions’ of events) for anyone who is interested.

Memento is a lovely film. My interpretation is that Leonard’s amnesia is caused by an inability to transfer information into long-term storage, but his short-term memory is intact. Something that struck me as odd is that fact that he says several times in the film, “I don’t have amnesia, it’s a problem with my short-term memory.”

When my father suffered from a stroke a few years ago now, (he died in 2007 aged 95). He could remember in precise details memories from his child hood, but could not remember me, his son.

I took him for drives around the New Forest where he was born. He couldn’t understand why the hedges weren’t being cut back properly, and could photographically remember all the details in Bransgore, where he came from as if it was still 1925. he still was puzzled who i was and had no idea about the old peoples home he was living in then

The world of Philip K Dick is where we seem to be heading, a very depressing thought.

I watched Memento in FILM 101 for narration. Very good, trippy film. A deep commentary on memory and reliability. (Also a thrilling ride.)

Using memory as a storytelling device has always interested me. The possibilities are numerous. These are great examples that you have picked. This is a very interesting read 🙂

It is interesting in that when done correctly, it’s like a spool of thread unwinding to reveal a masterpiece in the spool itself.

Marjorie Prime was interesting. None of us remember the dead, only that part of the departed we choose to remember. There was a SF story I read as a child, an immensely rich man far in the future will pay any price to get the love of his life back. Cut-to-the-chase, some `scientists` actually resurrect her – how is unimportant – he meets her, but after says how impressed he is by their fake. Her memories seem perfect, but he knows it is not his lost love because she is not as smart, or as beautiful & her laugh is nowhere near as captivating as that of his lost love. So he continues his hopeless quest, for an ideal that never really existed & the scientists must tell his lost love, that he has rejected her.

The android in Ex Machina would have killed you.

This sounds intriguing.

They could have just re-made Memento without telling anyone it had been done before. Fans would have appreciated the irony.

It’s about time too. The original was a shameless rip-off of this remake.

I hated Jim Carrey until I was made to watch Eternal Sunshine…

Still don’t like his ‘manic comedy’, but that’s and awesome film and he’s simply fantastic in it…

I loathe his persona in those “manic comedies” but he’s fantastic in Me, Myself & Irene.

The scene in the corner shop where his facial expression shows his change from being a put-upon low status victim to becoming a confident bully is physical comedy at its best.

Agreed, great film.

If you haven’t already watched in, The Truman Show is another that Jim Carrey is great in.

Can we just take a moment to appreciate how the plot is so simple in Memento yet profound at the same time? Nolan’s more popular flicks like Inception have little too much happening for the human story to take center stage. This is why Memento still remains my fav Nolan movie.

Yes, the brilliance isn’t in the plot itself, but the way it’s structured. It makes it unique since a lot of the time a movies’ plot is what keeps movie watchers engaged. Not so here, it was more the watcher wanting to find out WTF is going on, and the sweet reward they get at the end for sticking around is absolutely satisfying.

Yes, yes, and yes.

One thing I never understood in memento was why Leonard can’t remember his wife was diabetic, since he has complete memory of everything up to the incident. Also, the film never explains where the name “John G” actually came from. And was it pure coincidence that Teddy had this name??? Surely Teddy would realise how dangerous the situation was for him under those circumstances?

Marjorie Prime is a really, really superb film. I don’t think I’ve ever seen better performances from Geena Davis and Tim Robbins, and Smith and Hamm are great too. I must see more of Almereyda’s work.

Memento is one of those great movies you have to watch two to three times in order to fully understand it.

Memento: proof that good filmmaking is mostly in the script and the director’s understanding of it, regardless of how much money you throw at a project.

Oh, this one definitely raised The Artifice’s profile. Brilliant read!

Enjoyable and interesting. I always enjoy reading an essay with a thoughtful perspective.

The use of a character’s memory or perception is a very fascinating way to communicate storytelling within this medium. As a common convention of an unreliable narrator providing an audience the narrative time and time again such as in films like Memento (2001), The Sixth Sense(1999), Fight Club (1999), Joker (2019), etc. These films use this device effectively and efficiently with confusing audience members.

[Spoilers for The Usual Suspects below]

A personal favorite is The Usual Suspects (1995) which I believe subverts the losing memories, amnesia, mental health storyline but provides a very creative outlook by making Keyser Söze the mystery of the entire film, the narrator of the story who calls himself “verbal”. This subverts the viewer and making the story based on the noticeboard in the police station is ingenious.

But unfortunately, I do find that the memory device has been oversaturated and needs to be used in both uniqueness and of course making sense within the narrative itself.

“The best tricks the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist”

I recall that there was a movie made in the 1940s or the early 1950s of the male protagonist getting whacked in the head, which triggered a memory loss where he couldn’t even remember his wife. The movie ended with him almost walking out from his wife, then getting hit in the head again. His memories returned and he went to his wife.

Eternal Sunshine and Memento are some of the best films out

I so appreciate the thread you have woven between classic films that play on memory and more recent science fiction films. Regardless of the depiction of technology at play, memory has such a strong hold on our conceptions of who we are and how we relate to others.