Orson Welles: The M. Night Shyamalan of Hollywood’s Golden Age?

At age 22, M. Night Shyamalan had graduated from NYU’s famous film school, and his first feature Praying with Anger was presented at the Toronto Film Festival. It even had a commercial release, for one week, in Woodstock, Illinois (bizarrely enough, the very same small town that Orson Welles grew up in, attending the Todd School for Boys). Shyamalan’s first huge gulp of success was The Sixth Sense, which he wrote and directed, was nominated for 6 Oscars, and grossed nearly 700 million dollars at the box office — having cost only 40 million to make, from the industry’s perspective, that’s a 1750% profit.

At 28, he had climbed to the top of the movie industry and was now trusted and set up to create more and more masterpieces. But every film he released following (with the exception of Signs) massively underperformed at the box office — his two most recent, The Last Airbender and The Happening weren’t even taken seriously by the audiences or the critics. It has gone so far that today, with After Earth, starring the Smith duo, Columbia Pictures has made a deliberate effort to keep audiences from knowing that Shyamalan is responsible for it — completely not mentioning him in the trailers or on the posters, except in the small print! — because they believe it would mean the film’s doom.

Some filmmakers have no problem replicating their success over and over again: Spielberg, Hitchcock, Allen, Chaplin, Edwards, Scorsese. While others never manage to repeat, let alone surpass, their first big hit. It’s easy for us to judge an artist from a distance and point out what they’re doing wrong, but for that artist himself to take an overview of their career as their living it in first-person, appears pretty impossible. But, luckily, history repeats itself. To better understand M. Night Shyamalan’s topsy-turvy career, perhaps a perspective of 7 decades can shine some light.

The Magnificent Orson

The magnificence of Orson Welles began in 1936, and started at the top. In the first years of his career as a director, 1936-1940, the speed at which Welles rose to international fame is legendary, making the whole process appear effortless. One perceives Welles as a boyish trickster, almost Shakespeare’s Puck, seeing how long he could keep this game going. Reviewing the achievements of his early life yields countless examples of the outrageous devil-may-care persona that drove his career — from lying his way into a role at the Dublin’s Gate Theater as a teenager, to directing on broadway, at only 21 years old, landmark modern adaptations of Shakespeare’s classics Macbeth and Julius Caesar — even being driven in an ambulance up and down the busy streets of New York City in order to get between rehearsals, meetings and radio gigs as quickly as humanly possible.

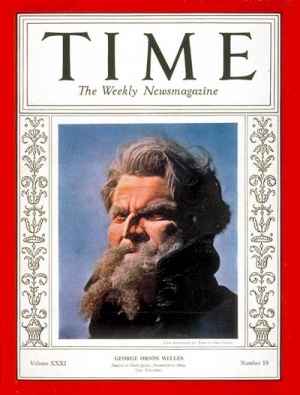

In a moment that symbolizes the inspiring relentlessness of theatre, Welles managed to successfully mount a production of the controversial socialist play The Cradle Will Rock, even in spite of the government locking him out of his theater to censor him. All the while as Orson Welles accomplished this in New York, his famous Mercury Theater on the Air radio programs, as well as his appearances on dozens of radio shows, were stretching out to every corner of the nation, so that by the time of Welles’ infamous War of the Worlds broadcast there wouldn’t be a household in the world that didn’t know the name Orson Welles. By the age of 23 he had achieved worldwide notoriety to such extent that he was on the cover of TIME magazine, and was even referenced across the Atlantic by Adolf Hitler (using the War of the World’s panic as an example of America’s fragility). Through all this, he began making a reputation for himself as a trusted entertainer, a brilliant storyteller, an innovator; the grand ringleader who puts on the perfect show.

In a moment that symbolizes the inspiring relentlessness of theatre, Welles managed to successfully mount a production of the controversial socialist play The Cradle Will Rock, even in spite of the government locking him out of his theater to censor him. All the while as Orson Welles accomplished this in New York, his famous Mercury Theater on the Air radio programs, as well as his appearances on dozens of radio shows, were stretching out to every corner of the nation, so that by the time of Welles’ infamous War of the Worlds broadcast there wouldn’t be a household in the world that didn’t know the name Orson Welles. By the age of 23 he had achieved worldwide notoriety to such extent that he was on the cover of TIME magazine, and was even referenced across the Atlantic by Adolf Hitler (using the War of the World’s panic as an example of America’s fragility). Through all this, he began making a reputation for himself as a trusted entertainer, a brilliant storyteller, an innovator; the grand ringleader who puts on the perfect show.

Starting in his radio programs, Welles presents himself as ‘the magical narrator’, his introductions for each story seemingly putting the audience into a trance under the spell of man’s echoing voice; America’s young 20th century bard. At the height of his game, Welles had established his persona as an unflinching genius. At this point in his career his shows on stage and radio were enjoyed by a wide audience spanning all of America, all age groups, and were very commercially successful. It is this reputation Welles was building that convinced the president of RKO Pictures in Hollywood, George Schaefer, to offer Welles the greatest contract offered in Hollywood still even to this day — he was given a two-picture deal with complete control over production, most importantly, the right to final cut of the film. After failing to get two potential film projects off the ground at RKO, in 1941 Orson Welles finally directed and released Citizen Kane.

There is no set of criteria that all films or filmmakers can be properly judged by. Naturally, films come in all different styles; at the extremes, there are those films that are only pure entertainment, and those films whose value is purely artistic. However, though there isn’t a set criteria for a “good film”, at the core of Cinema is a medium of storytelling, and show-business. Although some films that are initially poorly reviewed (only because they were ahead of their time stylistically) do gain popularity over time with a cult following — these are the exceptions; for the most part, the audience’s reaction to the premiere will decide it’s overall place in history, either at the top of the lists or the bottom. Films may deal with themes of society, history, artistic issues, existential musings, etc., but Cinema is ultimately the business of putting on a show for an audience that they will enjoy; this should never be a filmmaker’s only concern, but it should always be their first priority. After all, frankly, Cinema is arguably just ‘professional playing make-believe’, dressing up in costumes and fooling around with swords and guns — filmmakers and actors get paid an awful lot of money and receive an awful lot of attention for their ‘playing’, so they should have the decency to put on a proper entertaining show for their audience. Certainly, a great filmmaker must also offer their own styles, themes, perspectives, innovations, indeed; but, as I’ve found as a young filmmaker in festivals and competitions, the thing that matters most is getting a reaction of satisfaction from your audience. A great filmmaker achieves Art and Entertainment simultaneously.

There is no set of criteria that all films or filmmakers can be properly judged by. Naturally, films come in all different styles; at the extremes, there are those films that are only pure entertainment, and those films whose value is purely artistic. However, though there isn’t a set criteria for a “good film”, at the core of Cinema is a medium of storytelling, and show-business. Although some films that are initially poorly reviewed (only because they were ahead of their time stylistically) do gain popularity over time with a cult following — these are the exceptions; for the most part, the audience’s reaction to the premiere will decide it’s overall place in history, either at the top of the lists or the bottom. Films may deal with themes of society, history, artistic issues, existential musings, etc., but Cinema is ultimately the business of putting on a show for an audience that they will enjoy; this should never be a filmmaker’s only concern, but it should always be their first priority. After all, frankly, Cinema is arguably just ‘professional playing make-believe’, dressing up in costumes and fooling around with swords and guns — filmmakers and actors get paid an awful lot of money and receive an awful lot of attention for their ‘playing’, so they should have the decency to put on a proper entertaining show for their audience. Certainly, a great filmmaker must also offer their own styles, themes, perspectives, innovations, indeed; but, as I’ve found as a young filmmaker in festivals and competitions, the thing that matters most is getting a reaction of satisfaction from your audience. A great filmmaker achieves Art and Entertainment simultaneously.

The films of Cinema history that are people’s favorites today — for examples, Casablanca, Gone with the Wind, Mary Poppins, Singin’ in the Rain, Some Like It Hot, The Godfather, The Shining, or Psycho — are films that audiences want to watch over and over again. The greatest of films are those that continue to be successful long after the year of their premiere, so that they’re beloved still even today, because they succeed at being fantastically entertaining and simultaneously wonderfully and beautifully creative. This is the highest status a film can reach, a “must-see classic”, and that is the most important role of the film director — to put on a complex show that people will want to watch and rewatch and rewatch. At the start of his career, you couldn’t find a storyteller better at this than Welles. While making technical leaps and bounds in each of the fields he touched, he presented stories both groundbreaking for the medium and riveting for the audience.

The films of Cinema history that are people’s favorites today — for examples, Casablanca, Gone with the Wind, Mary Poppins, Singin’ in the Rain, Some Like It Hot, The Godfather, The Shining, or Psycho — are films that audiences want to watch over and over again. The greatest of films are those that continue to be successful long after the year of their premiere, so that they’re beloved still even today, because they succeed at being fantastically entertaining and simultaneously wonderfully and beautifully creative. This is the highest status a film can reach, a “must-see classic”, and that is the most important role of the film director — to put on a complex show that people will want to watch and rewatch and rewatch. At the start of his career, you couldn’t find a storyteller better at this than Welles. While making technical leaps and bounds in each of the fields he touched, he presented stories both groundbreaking for the medium and riveting for the audience.

Citizen Kane is the peak of this perfected expression by a flawless young storyteller. If there are a few dips or flaws to the production, they are so minute that they can be overlooked in order to see the film as the piece of perfection that it is — a brilliantly constructed mystery, produced by the finest technical team available in Hollywood in its day, with the boy genius leading the charge, bringing his brash innovative approach to storytelling.

Citizen Kane is the peak of this perfected expression by a flawless young storyteller. If there are a few dips or flaws to the production, they are so minute that they can be overlooked in order to see the film as the piece of perfection that it is — a brilliantly constructed mystery, produced by the finest technical team available in Hollywood in its day, with the boy genius leading the charge, bringing his brash innovative approach to storytelling.

Citizen Kane was incredibly well received by the majority of critics; however trouble was made for the film’s release by William Randolph Hearst (for obvious reasons) and as a result, a delayed release led to the film barely recouping its budget, bringing no profits at all to RKO. It was in this time, directly after completing Citizen Kane, that Welles’ career hung in the balance. The hardships of Welles’ entire life to follow are a result of his missteps between 1941 and 1942; the catastrophic difficulties of his various unfinished/ ”finished” projects in this time forever ruined his hopes in Hollywood. While finishing Citizen Kane he needed to pick a next project, but he was unable  to make a fast decision.

to make a fast decision.

Though Citizen Kane was getting hailed as a masterpiece — Bosley Crowther of the New York Times calling it “the most sensational film ever made in Hollywood” — the ‘Movie-Making Business’ doesn’t care about praise from critics, they want Orson to make them a profit.

“Without question, Citizen Kane would enhance his artistic reputation, but it was extremely long coming, it was a financial question mark, and there was still the matter of well over a hundred thousands dollars expended on questionable projects that would almost surely never see the light of day.”¹

Welles desperately had to prove himself a bankable investment, but he was still in a safe position — he simply had to select the next story he’d work on for RKO. He planned on adapting Alexander Calder-Marshall’s The Way to Santiago, and began spending RKO’s money on preproduction for this film — the story seemed right, it was an espionage thriller with two lead roles for Welles and starlet Dolores Del Rio — with Orson’s touch, surely he could turn this dime novel into a classic. However since the film was set in Mexico, they would have to obtain permission from the Mexican government to shoot there — but Mexico wouldn’t allow RKO to shoot because they were concerned about getting involved in WWII and offending the Germans. There was nothing Schaefer or Welles could do back in Hollywood and so this project crumbled — it seems for a time Welles entertained the notion of having the director Norman Foster in charge of direction of this problem production, with Welles just staying only as a producer and actor, freeing him to move on to the next idea — but the idea was scraped, more costs-to-date all now wasted, and Welles needed another story.

“At this point he reviewed more than 40 possible subjects with an RKO story editor — everything from a life of Beethoven to The Brothers Karamazov and To Have and Have Not.”¹

It is in these next months that Welles begins to overestimate his power and remaining luck in Hollywood, as he starts to stretch himself pretty thin between three floundering projects. He was in essence trying to establish himself as an independent producer working from within Hollywood’s system, with a core production team working for him (the Mercury Players and his key crew members,  including cinematographer Gregg Toland among others).

including cinematographer Gregg Toland among others).

“Welles’s contract had been amended to reduce the number of functions he was required to fulfill… This strengthened his position as a producer: he could nourish his dream of a long-term production unit and initiate projects without having to direct all of them.”¹

I would say it was Welles’ miscalculation that this dream was already within his grasp that led him to not properly managing these projects. Had he focused on finding one project to devote all his time to, that was both a satisfying choice for the studios and a juicy subject matter for his creative mind, he may have successfully completed even one of the five film ventures he began from 1941 to 1942 — not to mention he still had finished only one of the two films promised in his original contract with RKO back in 1940. His accountability was dwindling. Three productions then began practically simultaneously.

Journey Into Fear was a thriller suggested to Welles by Schaefer — for once, Welles listened to Schaefer’s advice and began working on it, penning the adapted screenplay himself — but it wasn’t long before he abandoned this film too, leaving it for someone else to finish. It’s All True was to be a “four-part story anthology” of “North American subjects”. But Welles gave his direct attention only to his third project, The Magnificent Ambersons — and was roughly watching over his other two projects from a great distance. Welles had managed to move forward from Citizen Kane with three films on his slate to be released in 1942 — but during the scramble to get these films green-lit by RKO, Welles’ contract was renegotiated, and having already shown how untrustworthy he was with logistics, deadlines, budgets, etc. — he was given less control in his new RKO contract, and his final cut privilege was revoked.

“Welles now had to accept that beyond the first cut, the studio now had the right to ‘subtract form, arrange, rearrange, revise and adapt the picture in any manner’. Once an almost free agent, he had been reduced to an employee.”²

In signing this contract before launching into these three doomed projects, Welles gave away his last trump card without realizing how much difference it could make. The Magnificent Ambersons was a troubled production from the first day of shooting and almost immediately ran way over budget. Then a complication occurred that was not Orson’s fault: Pearl Harbor.

“Welles was being subjected to criticism for his draft-exempt status, and [a] South American [Inter-American affairs] venture would give him an opportunity to enlist his talent in the service of a noble wartime cause. RKO was willing to cooperate because the State Department would partly underwrite the project. The idea on which Welles settled was to make a South American version of It’s All True.”¹

So Welles finished his shooting of Ambersons on January 22, 1942 and headed down to Brazil. What had already been shot for the North American version of It’s All True was, once more, all a waste and thrown out, and the director of that shoot’s second unit, Norman Foster, was reassigned to the now director-less Journey Into Fear. On February 8, 1942 Orson Welles would leave Hollywood the troubadour of America — but that Welles would never return — the man who tried desperately to retake his seat on the throne he abandoned would instead return to be labeled an untrustworthy profligate as a result of the devastating failures of every single ‘Orson Welles Production’ of 1942.

As a result of Welles not seeing Ambersons to its finish, the studio was able to recut it and, according to Welles and most others who worked on the film, ruin it as a story, trying to artificially gear it down to a younger audience than it was intended for by reshooting and reediting. While Welles’ foreign film venture was racing out of control, behind schedule and over budget, RKO was simultaneously disappointed with the state of Welles’ Hollywood production, Ambersons — though the reviews of Ambersons from the Pomona test-screening ranged from some praising it to the highest degree as cinematic genius, to the majority loathing it.

Even the positive reviews expressed a concern for its ability to appeal to most audiences, giving RKO the impression that they had a dud on their hands — an expensive dud, the latest in a string of expensive duds Welles was responsible for. Journey Into Fear’s screen-test reception was “decidedly cool”² as well. “This was a cause of deep concern to RKO, as both films had gone over budget.”² George Schaefer was fired at RKO as a result of his continuing support of Welles. It’s All True’s production was in shambles, and so RKO scraped it and recalled Welles to Los Angeles, where “RKO’s new bosses argued that Welles’ contract was null and void and did their best to discredit the undisciplined and extravagant filmmaker.”² He is cut loose from RKO. How did the world’s stance on Orson Welles reverse so drastically in under two years? From trusting a 24 year old with absolute control of a Hollywood production, to deeming that same man — the man who had delivered the undeniably revolutionary masterpiece Citizen Kane — too “undisciplined and extravagant” to be trusted with another film’s budget. John Houseman, possibly Welles’ closest collaborator, attributes the blame to absolutely no one but Orson himself — “No one was stopping him from making another Citizen Kane”¹.

In Hollywood it would seem you can be either a pain in the ass and a box-office smash, or a joy to work with and a box-office gamble — but what you cannot be is a pain in the ass and a box-office gamble. By this time, Welles was more a catastrophe than a gamble — every single production he had taken control of was hundreds of thousands of dollars over RKO’s specific budget maximums, and yet only one complete Orson Welles film existed, and even that one barely recuperated.

The recut Magnificent Ambersons and Journey Into Fear (whose opening was delayed almost a year) performed poorly at the box office. I believe the finest of artists are such, not because they revolutionized their medium, or because they sold the most tickets, but because they paid more attention than anyone else to the last, minutest detail of their work; the beauty is in the finish. Kubrick, Hitchcock, Kurosawa, Hawks, Ozu, Antonioni, Lang, Chaplin, Wilder, to name only a few — the works of these men display such careful attention to every intricate detail, as the story is spun by the story’s master, ceaselessly polishing his work’s finish. There are many of Orson Welles’ films as well that are exquisitely finished, the best example naturally being Citizen Kane. But the man failed to see to the finish even one of the plagued productions he was responsible for in 1942, and wasted what would today amount to millions of dollars of RKO’s funds.

He left the country as his productions were being finished by other people — it’s no surprise that these others could not finish Orson’s work for him, they weren’t the same caliber of artist as he — but it is his fault that he was not where he should have been, finishing his work, properly. Welles has no one to blame but himself for being a distracted craftsmen who lost sight of his job, who ran off to the Southern hemisphere and left others at the helm to finish his work. It seems to me that following the success of completing Citizen Kane, Welles got distracted from his duties as a storyteller, an entertainer on the world’s stage. He tried to become both director and producer simultaneously — deluding himself that he already controlled an enterprise of film production, enough that he could step back and start overseeing multiple productions — when clearly he couldn’t manage to control all simultaneously, and as a result he personally wasted a gigantic sum of RKO’s money on four films that never saw the light of day, and three finished films, only one of which anyone considered to be a good movie.

A big trick of being a filmmaker is managing to be a successful enough entertainer of your audience, so you can get away with your personal artistic expressions. Welles had managed this brilliantly up till and including Citizen Kane, but following that, he stopped trying to wrap up his art in an entertaining package of fun for the world. If Welles had picked a single project out of all he considered (either staying with Journey Into Fear, or Brothers Karamazov or Beethoven, any definite selection), focusing his mind on directing rather than producing, and then carried this project out to a successful end (“successful end” being a movie that, like Kane, is experimental and innovative but simultaneously gripping, amusing and dazzling for an audience), then it appears Welles’ career would have continued on the same rising trajectory it had always been on. But after Kane, the way Welles addressed his audience changed. Instead of the Master of Ceremonies persona, with ‘a devil of a tale to tell us all’, Welles began to be perceived by his audience as talking down to them, solely trying to educate them.

As one audience member said for a review of Ambersons, “make movies that make people forget, not remember…people like to laugh.”³ Schaefer pleaded with Welles to understand this in a memo sent down to South America: “Orson Welles has got to do something commercial. We have got to get away from ‘arty’ pictures and get back to Earth. Educating people is expensive…and your next picture must be made for the box office.”³ Schaefer tried to convince Welles people don’t go to movies in order to be educated — at least, they don’t go solely to be educated, they must at least be intrigued first, and then taught a lesson — but from this point on in Welles’ career, he has less time to spare for levity and fun.

As one audience member said for a review of Ambersons, “make movies that make people forget, not remember…people like to laugh.”³ Schaefer pleaded with Welles to understand this in a memo sent down to South America: “Orson Welles has got to do something commercial. We have got to get away from ‘arty’ pictures and get back to Earth. Educating people is expensive…and your next picture must be made for the box office.”³ Schaefer tried to convince Welles people don’t go to movies in order to be educated — at least, they don’t go solely to be educated, they must at least be intrigued first, and then taught a lesson — but from this point on in Welles’ career, he has less time to spare for levity and fun.

We see this change of Welles’ artistic voice shift before our very eyes while watching Magnificent Ambersons — the opening montage, with a traditional Welles narration, has a clever, magical, clever fun quality to it — its pace is sustained by several moments of comedy (provided with great help from Joseph Cotten’s performance), but then the story takes a sharp turn and plummets into the dark and serious. “The opening montage, the Ambersons ball, and the snow scene are masterfully conceived, but after this the pace begins to drag and Welles’ script increasingly becomes a succession of dialogue set pieces — like a script for a radio show. For the only time in one of his major productions, Welles declined the leading role in Ambersons. Tim Holt is not unengaging, but both the technical requirements of performance and dramatic subtleties of the role are beyond his capabilities.”¹ As Robert Carringer argues, I too don’t believe the blame for Ambersons’ failure should go to the studio for butchering the film with a recut. Though I don’t doubt that the recut ruined the overall style of the film, I think it was already a story that people were not going to enjoy.

I would blame Ambersons’ inability to appeal to an audience on the combination of Welles’ drawn out script and a lack of likability of Tim Holt, who tries to carry the movie but is not strong enough an actor. For an artistic mind who had such a blatant knack for when to include essential story elements of comic relief, sentimentality, sensationalism and razzle-dazzle, as is illustrated clearly through Kane — approaching Ambersons, Welles made little to no attempt at injecting these and other elements of showmanship into this script — a move so remarkably uncharacteristic of the “Wizard of RKO”, a master of showmanship, till then. If it isn’t the studio’s recut that’s blamed for Ambersons’ failure, then it’s that the expectations were too high after the success of Kane — but high expectations never affected Welles in the past; after all, could the expectations have been higher after the War of the Worlds scandal? If a comedian is getting laughs the whole night, and then a joke doesn’t get any, one doesn’t blame the audience, they blame the comedian for telling an unfunny joke.

I would blame Ambersons’ inability to appeal to an audience on the combination of Welles’ drawn out script and a lack of likability of Tim Holt, who tries to carry the movie but is not strong enough an actor. For an artistic mind who had such a blatant knack for when to include essential story elements of comic relief, sentimentality, sensationalism and razzle-dazzle, as is illustrated clearly through Kane — approaching Ambersons, Welles made little to no attempt at injecting these and other elements of showmanship into this script — a move so remarkably uncharacteristic of the “Wizard of RKO”, a master of showmanship, till then. If it isn’t the studio’s recut that’s blamed for Ambersons’ failure, then it’s that the expectations were too high after the success of Kane — but high expectations never affected Welles in the past; after all, could the expectations have been higher after the War of the Worlds scandal? If a comedian is getting laughs the whole night, and then a joke doesn’t get any, one doesn’t blame the audience, they blame the comedian for telling an unfunny joke.

Welles had an excellent track record of satisfied audiences on stage and the radio because the stories he told them were full of fun and dangerous characters; pirates, aliens, murderers and tycoons. But then with Magnificent Ambersons he selects a story with characters that are far from exciting. The subject of a small town’s changing social scape from rural to suburban due to the industrial age, and a family’s downfall as they refuse to change with the times, is not in the same genre as almost all of his works before. The group of characters in Ambersons are quaint and genteel, in essence not that rousing — and though a man’s downfall is a great story, the audience must first relate to that character.

To watch Charles Foster Kane’s fall is tragic because you initially like him, then hate him, then pity him, and ultimately sympathize while being disgusted with him. The Magnificent Ambersons’ lead character, George Amberson, is a prick in the beginning, a prick in the middle, a prick in the end, and then he “gets his comeuppance” as the narration goes. Instead of the cavalcade of entertainment one finds in Kane, Ambersons feels more like an english novel, with similar characters and social schemes in fact. I wonder if it is that quality to Booth Tarkington’s original novel that sparked Welles’ interest. Having spent much of his childhood growing up mostly in Europe, perhaps Welles was often in the company of those who spoke of America as a ‘young nation without any real history.’ Perhaps what drew him to this story is the ‘American historical’ tone of it, feeding a desire of his to portray his country as having a classical history. He desired to portray the aristocratic social sphere, that Welles had himself always been an outsider looking in on — as he toured Europe with his mother, moving constantly from country to country, but always hobnobbing with the upperclass: the wünderkind who’d entertain groups at parties with magic, visiting, but never belonging by blood to the same tier of men. So the filmmaker portrays the upperclass as cold and cruel, till the audience deeply dislikes the characters — and yet a part of Welles still wanted to belong, and that’s what made him find these characters quite intriguing.

To watch Charles Foster Kane’s fall is tragic because you initially like him, then hate him, then pity him, and ultimately sympathize while being disgusted with him. The Magnificent Ambersons’ lead character, George Amberson, is a prick in the beginning, a prick in the middle, a prick in the end, and then he “gets his comeuppance” as the narration goes. Instead of the cavalcade of entertainment one finds in Kane, Ambersons feels more like an english novel, with similar characters and social schemes in fact. I wonder if it is that quality to Booth Tarkington’s original novel that sparked Welles’ interest. Having spent much of his childhood growing up mostly in Europe, perhaps Welles was often in the company of those who spoke of America as a ‘young nation without any real history.’ Perhaps what drew him to this story is the ‘American historical’ tone of it, feeding a desire of his to portray his country as having a classical history. He desired to portray the aristocratic social sphere, that Welles had himself always been an outsider looking in on — as he toured Europe with his mother, moving constantly from country to country, but always hobnobbing with the upperclass: the wünderkind who’d entertain groups at parties with magic, visiting, but never belonging by blood to the same tier of men. So the filmmaker portrays the upperclass as cold and cruel, till the audience deeply dislikes the characters — and yet a part of Welles still wanted to belong, and that’s what made him find these characters quite intriguing.

“He hoped that he might yet take a popular audience with him as he peered over the precipice, down into the abyss…The Magnificent Ambersons was just the kind of popular classic that Welles sincerely believed could bridge the great divide in Hollywood between art and commerce.”³

Welles must have deliberately chosen to ignore the warning that even Booth Tarkington gave of his own book and about dramatizing it, strongly discouraging it as “a young audience in the theater would be not scornfully amused but vaguely angered”³ by it. The young Orson Welles was a master at balancing levity with profundity. He could do it on any scale — through the overall arch of an entire production, or simply by using his melodic vocal chords to bellow the delivery of just one sentence, so you laugh at the start and tear up by the end. I believe the man’s view of his place in this world changed, and so he changed as a storyteller. Before he was a brash joker, fresh out of the Todd School for Boys, his entire career being one big prank on the world, as his panache alone made every work he touched shine. He was the zeitgeist personified; the nation’s raconteur extraordinaire. But he did not strategize his career in Hollywood well at all.

Few men have been as lucky as Orson was to get the chance to make a masterpiece like Citizen Kane, let alone have final cut on their first Hollywood film. When he gave up that right, he let go of his grip around Hollywood’s neck. Then when he left Ambersons behind to crumble as he dreamed up the next project — that was the mistake he could never fix. Had he been more focused on taking his career one project at a time and seeing things out to the end, I don’t believe his career would have been ruined the way it was; even if Ambersons had still been a failure, he wouldn’t have burnt his bridges and gotten the reputation of unreliable and wasteful of other people’s money, which is the foremost reason for his downfall. Of course, Orson Welles remained a great filmmaker after Kane and after Ambersons and till the end of his life — in fact, I would call F for Fake his finest film.

He is undeniably the most resourceful filmmaker of all time. He never ceased being an amazing innovator of the art of Cinema. But for the rest of his career, the pattern that Kane/Ambersons points to continues to be the crucial difference between a hit or a miss. Touch of Evil, Lady from Shanghai, F for Fake, Mr. Arkadin, and his performance in The Third Man — the style of each of these films is fun, exciting and mischievous. In F for Fake he achieves a playful interaction with the audience exactly like he’d manage to 50 years earlier with his radio shows. This is Orson Welles in his element — a little magic and ‘hankypanky’ — that is the kind of story he told better than best, the evidence being that these are the films of his that audiences wanted to watch, and now rewatch. Orson’s heavy-handed productions — The Magnificent Ambersons, Macbeth, Othello, Chimes at Midnight, The Immortal Story — these projects were a part of his personal dream to capture himself performing each of these giant roles and make permanent his adaptations of these great works on film. These are the films he personally felt he had to make as an artist voice — but they weren’t the films audiences were going to sit down and watch, not very often. Perhaps because I’m a young filmmaker I overvalue the need to satisfy an audience. But frankly I believe it is the best use of an artist’s time not to make the works that benefit yourself, but the works that will benefit your fellowman.

An artist’s job is an endless struggle to find a personal beautiful experience that can be enjoyed universally — a story that becomes a classic story we all can turn to, a Canterbury tale or a Grimm fairytale, a paramount example of storytelling, with the timelessness of, say, It’s a Wonderful Life, or Gone with the Wind, or in fact, Citizen Kane. But many artists’ journeys get sidetracked on a battle to find their own way of expression that will satisfy firstly their own cravings, and probably in doing so satisfy their admirers, but fail to reach the majority of their audience. I think it is wrong for an artist to blame his audience when they don’t understand him or her; this comes out of the artist’s ego and stubbornness, and frequently leads an artist to become hostile towards their audience for not agreeing with him that he’s smarter and specialer than them. I say it is his own fault for not speaking the proper language with us, not making the effort to communicate; dammit, is that not what all of this was for, ultimately, just for one man to communicate with all mankind, for all mankind?

There is a fine line between considering your audience and simply pandering to it that a great artist does not cross — ultimately, he or she contains some kernel of talent that makes their perspective of the world worthy of discussion, and they must have faith in their own voice — the difference does exist between undignified pandering and impeccable tailoring. But, honestly, artists, much like philosophers, do not contribute anything inherently valuable to the world. While other’s have the decency to get a real job, baking bread so people don’t starve and cobbling shoes so people don’t freeze, artists just sit in their studio, and ponder, till that pondering leads them to create and make themselves feel fulfilled. We muse and work out our personal conundrums, and the product of that labor is an artist’s expression — bravo, some help that is. I believe an artist owes society something gigantic in return; he or she owes the world a work that will improve their life, not the artists, one that they find intriguing and brilliant, and that justifies the artist sitting on his ass all day long to think about himself and his “voice.”

After Welles left Hollywood — after he quit trying to win back Hollywood’s favor by playing by their rules as much as he could muster and producing works that, I would say, have an odd indecisive style to them — after Welles got his ‘comeuppance’ much like the character of Magnificent Ambersons, two Orson Welles-s finally emerged. With a new modus operandi to his filmmaking, “Orson Welles, the Performer” went on to direct his Shakespeare adaptations that all star himself, and “Orson Welles, the Showman” went on to direct several more classic films; as an artist back on track to giving the audience what they want he developed two products, his performance and his show. Whether a film does good business on the day of its release is ultimately immaterial, provided it does eventually do some form of good business; films like Vertigo or The General, and all films that are now of ‘Cult’ status, have managed to reverse their initial failings and finally show a profit — they now have a fan base that spends money on this product.

Dollars being spent by an audience is the only thing that saves a film from sinking into obscurity. But a film that does poorly when it’s released, and does not gather a following over time, never manages to do any good business and is quickly forgotten; I can’t think of any examples, as these are the films I mean. Both of the older versions of Welles delivered products that did poorly initially due to his still ruined reputation. However eventually they did turn a profit, as the public’s view of Orson slowly reverted back to that of admiration. But this is a recent transformation — up until basically the 21st century, none of his later films managed to please his audiences.

Now with their Criterion Collection releases and inclusion in all important film catalogues and internet movie services, his later films are finally as present today on the world’s stage as, say, even Gone with the Wind. Now that his films are marketable, they have finally become successful films. However his productions from 1942 to 1958 (with the exception of Lady from Shanghai) remain obscure to all but Orson Welles-scholars, and there is no worse damnation of an artist’s work than invisibility. Welles was a great artist, and a great filmmaker. He couldn’t help constantly innovating all mediums in boundless ways. But, I believe Orson served this world best in his youth, when he still had an ear keyed to his audience’s laughter and applause, and not just the sound of his own magnificent voice.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

He had plenty of opportunities after Kane. The guy was brilliant, but he made films that weren’t bankable and had horrid luck with studios. It’s certainly arguable that he was the most talented director of all-time.

It’s funny how Orson Welles has become something of a shorthand or synecdoche for unfulfilled early promise. In Will Self’s wonderful novel ‘Walking to Hollywood’ the author himself (or, at least, a character who shares his name) has dinner with Bret Easton Ellis, who is ‘played’ in Self’s bizarre, film-inflected fantasy by Orson Welles – ‘Mid-period Orson Welles,’ no less: ‘the Welles glimpsed only briefly on camera during the shooting of his Rockefeller-funded South American travelogue.’ (Self is ‘played’ in this scene by Pete Postlethwaite, and in others by David Thewlis – read the novel, it’s mind-bending). Also, remember the funny scene towards the end of Tim Burton’s ‘Ed Wood’ where Orson Welles (played by Vincent D’Onofrio) assures the downcast main character that ‘visions are worth fighting for’? Also, this: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6i7ycxiog40

A particularly interesting film of Welles’s to look at from this perspective is ‘The Trial’ which, as I understand it, was the film he had most creative control over post-Kane. Roger Ebert’s review is a great read, and I quote from it:

“But there is also another way of looking at “The Trial,” and that is to see it as autobiographical. After “Citizen Kane” (1941) and “The Magnificent Ambersons” (1942, a masterpiece with its ending hacked to pieces by the studio), Welles seldom found the freedom to make films when and how he desired. His life became a wandering from one place to another. Beautiful women rotated through his beds. He was reduced to a supplicant who begged financing from wealthy but maddening men. He was never able to find out exactly what crime he’d committed that made him “unbankable” in Hollywood. Because Welles plays the Advocate, there is a tendency to think the character is inspired by him, but I can think of another suspect: Alexander Salkind, producer of “The Trial” and much later of the “Superman” movies, who like the Advocate, liked people to beg for money and power that, in fact, he did not always have.”

The Trial is a hell of a film. Very daring, a brilliant adaptation of Kafka’s style to a cinematic language. And of course the scrutiny of beaurocracy does have some parallels to the filmmaker’s feelings towards “the establishment”. And if you watch Orson Welles’ Sketch Book (his 1955 tv show), Welles makes many comments about man’s endless battle against fascism and disguised-police states — again similar to The Trial.

I love Vincent D’Onofrio in Ed Wood — except that Burton had to dub his voice, using the marvelous Maurice LaMarche (Pinky and The Brain) doing his Welles/The Brain impression. You can see D’Onofrio’s subsequent perfected Welles-performance in a short he directed and starred in called “Five Minutes Mr. Welles” (avilable on YouTube) – a nice performance of Welles while he was acting in The Third Man (though the film exaggerates how much Welles backseat-directed Carol Reed’s masterpiece)

As for Welles’ doomed South American project, there’s a very sad story there — the discouraged Welles down in Brazil was trying to finish It’s All True. Fed up with LA, he was trying to make an honest documentary of the colorful native life of the Ipanemians — but the main character of the story, a local hero and sailor, was tragically killed while he and Welles were shooting a recreation of the man’s heroic sea exploits — the death crushed Orson. This tragedy ended the film’s production, and Welles returned to Hollywood quite defeated.

I found this an interesting article to read, because I remember watching a video where the narrator said he thought M. Night might have gone on to become the 21st century’s Hitchcock.

I’m curious about what you thought of ‘The Stranger’.

The Stranger is such an interesting case, I was going to include a section about it in this article, but it really deserves an article all of its own. It’s a fine film, but I get the feeling that Welles was trying to tread lightly-stylistically while making it — unlike all of his other hollywood films (ambersons, lady from shanghai, touch of evil, etc) the studios did NOT massively recut it to try to make it conform to Hollywood traditions, because there was no need — it seems like he was trying to not make any waves, so many of his unique style-traits (long takes with complex blocking and camera movement, rapid editing, montages, a narration, etc) are absent. He was conforming — and as a result the film doesn’t shine with his usual brilliance. Some great filmmakers manage to be shine while still conforming to the usual ways. But Welles was a constant experimenter, and when he doesn’t try anything daring his heart just doesn’t seem in it.

That being said — it’s not a bad movie/story, some nice cinematography — and it has a place in cinema history as the first film to show holocaust concentration camp footage (in 1946!), in a scene some have called a parallel to the famous Newsreel scene in Kane.

His next film, Lady from Shanghai, was incredibly experimental, but because of that the Studios massively recut it — after seeing the butchering, Welles sent a detailed memo about everything that must be fixed, in which he literally mocks the film minute by minute (the same cut that exists today). So the film that we can attempt to enjoy was personally hated by Welles, but id say what does still exist of his vision is wonderful but surrounded by chaos — I’d at least take a butchered Welles-masterpiece than a film like The Stranger, which Welles himself, as he confessed to Peter Bovdanovich, felt has the least of himself in it of all his films.

Great read. I personally think Welles got better as a filmmaker after Kane. Kane’s technical innovations cannot be overstated, but Welles’ later films have a much more artistic appeal.

Comparing anyone to Shyamalan is harsh, but I see what you mean. It’s a lot of information to help us learn about a very interesting mind.

Love the article. Very controversial. Raised an eyebrow when a I first saw the title. Won me over by the end.