The Problem of Peter Pan: Should Choices Hurt?

There is no denying that Peter Pan, the story of “the boy who wouldn’t grow up,” has resonated with audiences in way few stories can hope to achieve. Everyone, it seems, derives something personal and profound from the story of a boy who never will leave behind his childhood to face the world as a man. If the world of a college student’s Facebook is any indication, such eternal youth is “a consummation devoutly to be wished” among many who find themselves thrust into the frightening landscape of adult responsibilities. Given the opportunity, would anyone willingly choose to face that vast, insecure, and unforgiving world of careers, family, and taxes?

While rarely remembered by those who love it and not laid out explicitly by the author, Peter Pan actually does find himself faced with this self-same question: is his carefree immortal childhood more important to him than happiness with another person, if that happiness means he must grow up? Given the choice, does he choose a carefree eternal youth, or a careworn adulthood with someone he loves?

Interpretative Key

Perhaps the first (and only) man to discuss this problem’s significance was G.K. Chesterton. An English journalist and prolific essayist, he addresses the question of criticism leveled at Peter Pan in an essay published in the London Times entitled “On Sentiment.” To summarize, he says that intense emotion as such in drama is nothing to condemn, but sentimentalism is intense emotion with some sort of deception attached to it: that is, “the evil is not in the recognition of the feeling as a fact…it is in the destruction or dishonouring of some other fact.”

For instance, the image of a soldier leaving his beloved to join his comrades on the field happens and has happened so often as to be almost prosaic; but, as Chesterton makes clear for us, “if we then make fancy pictures of war, and refuse to admit that wounds hurt, or that heroes can be killed, or that good causes can be defeated, then we are trying to hold two contrary conceptions in the mind at once. We want to admire the soldier and deny what is admirable in him.” Sentimentalism thus consists in wanting the thrill of an emotion that comes with something admirable, or pitiable, but then denies or ignores the harsh reality that cannot be evaded.

The Problem

All well and good, but what has this to do with Peter Pan? As shall soon be made evident, it may determine whether or not Peter Pan ultimately works as a story. What critics of his time derided as sentimental, were actually honest depictions of the actions of what, say, a bereaved mother would do in such circumstances. The problem with Peter Pan is none of those things. The problem with Peter Pan, as expounded for us by Chesterton, is this:

“Yet there is something that rings false in the play…What is really wrong with that delightful masterpiece is that the master asked a question and ought to have answered it. But he could not bring himself to answer; or rather he tried to say yes and no in one word. A very fine problem of poetic philosophy might be presented as the problem of Peter Pan. He is represented as a sort of everlasting elf, a child who never ages age after age, but who in this story falls in love with a girl who is a normal person. He is given his choice between becoming normal with her, or remaining immortal without her…He might have said that he was a god, that he loved all but could not live for any; that he belonged not to them but to multitudes of unborn babes. Or he might have chosen love, with the inevitable result of love, which is incarnation; and the inevitable result of incarnation, which is crucifixion; yes, if it were only crucifixion by becoming a clerk in a bank and growing old. But it was the fork of the road; and even in fairyland you cannot walk down two roads at once.”

What Peter chooses is to come and visit Wendy every spring and bring her to Neverland. But if Wendy ages and he never does, to what purpose is that? According to Chesterton, the compromise ends up being worse than the choice. For, in no time, it will not be Wendy he takes back. After a short while, if he remains a child, he will be giving her up forever whether he likes it or not. The reason for the compromise is entirely negated. In attempting to have it both ways, he has neither, or one tinged with regret and uncertainty. And this, Chesterton concludes, is truly the worst sort of sentimentalism.

Peter Pan is an Immortal elf sort of child, forgetful, mischievous “innocent and heartless,” as Barrie describes him. Since he is eternally a child, he would this all if he decided to return to England and grow up. And, of course, growing up would mean saying goodbye eternally to Neverland. Many times in the story he insists that never will such a thing happen. But, he falls in love with Wendy–what, then, will he do? If he remains young, he forgets her and moves on, but if he decides to stay with her, he must settle for a mundane existence, and, yes, grow up. He does make, or rather accept, some sort of compromise, but is it really satisfactory? As Barrie makes explicit, it is not Wendy he takes back to Neverland, eventually, but her descendants. Is he really getting what he wanted?

An Objection

Such is the problem, as we have laid it out. But, can we say the Chesterton is right in his criticism? Does the story of Peter Pan demand this sort of choice: a heartrending, irreversible choice causing suffering no matter which path is chosen? There are some who may argue Chesterton reads more into the story than is strictly warranted. The story, after all, is a primarily a children’s story, filled with fairies, flight, pirates, indians and all sorts of happenings uniquely suited for a boy’s fantasy. Wendy is nearly killed through the agency of a jealous Tinkerbell, Peter nearly drowns saving Tiger Lily, many of the Pirates and finally Captain Hook himself are killed in the final stand-off (by the children, no less), and yet Barrie treads these incidents with a childish nonchalance almost, brushing grisly reality aside for the romance of the adventure. As Peter idly reflects as the water rises to drown him following the rescue of Tiger Lily, “to die will be an awfully big adventure.”

In a world where death and dying appear to arouse little distress, why then should Peter have to make such a dire choice as Chesterton says he must? Would not Peter’s compromise be more in keeping with the careless, boyish indifference of the character? Would that not be more fitting–a childish choice for a childish character?

These claims, their truth notwithstanding, have no effect on the “rules” of the drama. All the preceding “signs” in the story point to the inevitability of having to make such a choice, as to the archetypes in which it partakes. An analysis of the critical closing scene will make clear our meaning, as well as Chesterton’s overarching point.

Our Response

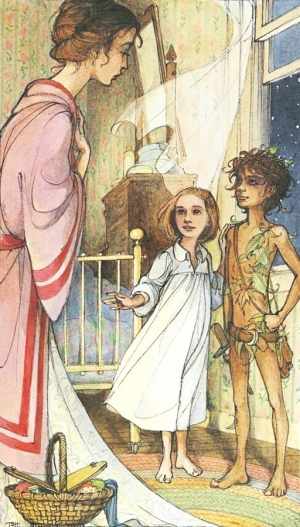

The Darling children have been returned to their home, with the coterie of the Lost Boys in tow. The household matters having now been smoothed over, Wendy speaks with Peter before he flies away. She asks him, “falteringly” if he wouldn’t want to speak with her parents about “a very sweet subject,” which he answers with a curt “no.” When Mrs. Darling comes to the window, she makes clear her intention of adopting him as well, but when she tells he’ll “soon be a man” he “passionately” tells her “I don’t want to go to school and learn solemn things…I don’t want to be a man. O Wendy’s mother, if I was to wake up and feel there was a beard!” Further efforts are likewise futile: “Keep back, lady, no one is going to catch me and make me a man.” Hence how they come to the compromise: Wendy’s desperation to see Peter again being plainly evident, Mrs. Darling agrees to let Wendy return with Peter to Neverland once a year for his “spring cleaning” and his reaction to the news is quite telling:

“Mrs. Darling saw his mouth twitch, and she made this handsome offer: to let Wendy go to him for a week every year to do his spring cleaning. Wendy would have preferred a more permanent arrangement; and it seemed to her that spring would be long in coming; but this promise sent Peter away quite gay again.”

Clearly, Peter has no desire to grow up; clearly, he also has some wish to stay with Wendy, and the conflicting wishes vie for supremacy within him. Up till the point of Mrs. Darling’s proposed compromise, the conflict is clear in Peter’s brusque response to Wendy, yet were one to judge based on the text alone, one might have concluded that Peter would prefer his eternal youth to becoming a man working in office, though married to Wendy. Though the compromise makes him “quite gay again,” the choice remains floating in the air, conspicuously unchosen.

Peter of course doesn’t care, but Wendy’s dissatisfaction is evident, for, as Chesterton would say, a choice that should have been made has not been made. Indeed, one might say they only put off the choice, rather than resolving the dilemma once and for all.

A good story requires a strong ending. All the signs in the story point to Peter having to make this sort of choice; not only little signs such as Wendy’s jealousy of Tinkerbell and Peter’s attempt to prevent the Darling children from finally entering their home, but also within the context of the above quoted conversation. Peter does not want to leave without Wendy, and Wendy cannot abide the thought of never seeing him again. Yet Peter recoils from the mere thought of growing up, a fact to which Wendy is now reconciled. While neither may be able to articulate the choices so starkly, they nevertheless recognize the choices for what they are.

Wendy has decided to grow up. Peter would rather it were not so. But, he cannot fence sit forever–in that case, the choice will be made for him. He must pick Wendy or Neverland, and embrace the pain that would come with either. Eventually, in the course of the story, it is not Wendy he takes back at all, but her daughter and granddaughter, thus nullifying the point of the compromise.The attempt to avoid pain and loss of some good only results in a worse evil. This, as Chesterton contends, was something Barrie should have recognized and didn’t, or did recognize and avoided.

Further Implications

Why doesn’t Peter take her back forever? Why doesn’t he leave her forever? Why does he refuse to make a real choice and instead for an ambiguous compromise? Why does Barrie himself refuse to make a real choice in the context of his own drama? One possibility is to reach into Barrie’s biography to see if any of the events of his life could possibly have influenced him in his titular character’s non-choice. And, such an analysis may indeed, in its own way, be fruitful, whether we examine his mother’s grief over the tragic death of his mother, or his relationship with the Llewellyn-Davies boys. Much that we unearth from his biography can in some way illuminate the more abstruse parts of the drama for us.

However, such information, interesting as it often is, more often serves to distract us from the drama proper. No, the answer to our questions lies not in a psychoanalysis of either the author or his biography, but rather we look for it within the context of the actual story.

Gay, Innocent…and Heartless?

More than once, Barrie says children are “gay and innocent and heartless.” Most among those who enjoy the company of children would agree with the first two adjectives, but be puzzled by the third. What does Barrie mean to say by calling children “heartless”?

Let us look at some examples from the drama itself: the phrase first appears as Wendy tucks her daughter Jane into bed. Wendy tells he daughter that when “people grow up, they forget the way [to fly]…because they are no longer gay and innocent and heartless. It is only the gay and innocent and heartless who can fly.” Perhaps we can best understand Barrie’s usage of the term if we consider it in context with its preceding adjectives. Children rarely reflect on the consequences of their actions, or how those actions will affect those around them. They are indeed gay, for they are untroubled by the darkness of the world, and pursue their own way. They are innocent by virtue of their ignorance of this darkness, which often arises in the human heart; they are heartless, for such innocence and gaiety makes them unaware of any suffering they themselves might unwittingly inflict upon another, and thus care little for the sufferings of others.

Usually, the thoughtlessness of children manifests itself only in small, petty acts, like the toddler throwing a tantrum when he can’t have ice cream before dinner, or leaving the breakfast dishes for Mom to clean up while he goes off to play. Children are not malicious of course, but rather are still learning their capabilities for causing pain in another, and that, oftentimes, another’s needs and desires must come before their own. But, in Barrie’s drama, the consequences of childish thoughtlessness, unbridled without the guidance of any adult, has disquieting, if not disturbing, consequences.

Stranger still, Barrie himself seems little troubled by the ensuing implications, appearing to believe such thoughtlessness is preferable to comparatively stifling world of the grown-ups. Now, he does not condone such thoughtlessness entirely (for instance, when Michael sees his father again, he comments, “‘He is not so big as the pirate I killed’… with such frank disappointment that I am glad Mr. Darling was asleep; it would have been sad if those had been the first words he heard his little Michael say”). But, though such thoughtlessness in not entirely condoned, nor is it condemned, however gently.

The point is, the “heartlessness” of Peter Pan seems to preclude his willingness to make such a painful choice. Being a forgetful, willful child with care for little else but his own happiness and fun, the compromise works just dandy for him. He never bothers to consider how it will affect Wendy or anyone else in the long run. Moreover, despite some swipes at Mrs. Darling for being “too fond of her rubbishly children,” he still seems to consider the careless freedom of childhood preferable to the constrained world of grown-up responsibility.

Such “heartlessness” would then in a sense be a good thing, as a part of that childhood. So, one could argue that Barrie knew exactly what he was doing in refusing to let Peter make the terrible choice. But, in letting Peter make such a lame compromise rather than making a difficult choice for himself, he removes what would make him compelling as a character.

Characters make choices. Even in stories driven more by outside circumstances (such as a disaster film) than the characters per se, nevertheless their choices play a significant role in the outcome of the story. In order for a drama to be successful, the characters must be faced with significant choices, choices that force them to sacrifice something they considered dear to them, something that will force them, in some way, to grow and change as a person. Barrie may have thought he was preserving his characters, or his audience, from undue pain, but in reality he unwittingly cheated both the audience and the characters of the denouement they deserve. He does not allow Peter to choose between rejecting Wendy and preserving his immortality, or rejecting Neverland and growing up with Wendy. Either choice, as Chesterton said, would be a fine one, allowing for a rich growth of character either way, but instead we get neither.

Peter clearly wanted to be with Wendy–as the drama makes clear, when he tries to bar the windows to the nursery, it’s because “I’m fond of her too. We can’t both have her”–but in the end he lets Wendy’s mother make the choice for him. Peter thus loses the chance to grow as a character. Instead of stretching his bounds, becoming something more than he was before, Peter remains the same as he was before, and will remain the same forever. All potential for growth, good or otherwise, has been utterly stunted by such a lame compromise.

The problem of Peter Pan is that Peter had a choice to make, a choice between two goods, and the rejection of either would result in some great suffering. By refusing to let his hero make this choice, Barrie, instead of helping his story, instead stultifies the power of his own drama.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

The strangest thing is that the story of Peter Pan, diffused through so many different mediums, re-invented, re-imagined, and re-appropriated so often, had somehow christened itself the children’s book of children’s books.

Peter Pan is a great fantasy book!

Adore this book i could read it over and over. my favorite message is that growing up is about more than being responsible its about living and loving and being happy like peter says “to live would be an awful big adventure”

The story is very much about not growing-up. Interestingly the stage productions almost always have Captain Hook and Mr Darling played by the same person, but Mr Darling is the epitome of some one who does not want to grow up (witness that he retreats from responsibility)

While we all get older… we don’t have to give up the beauty of being young.

I found your use of Chesterton, as a way to analyse Peter pan to be excellent, in that it illustrated that Peter Pan took the worst possible path in life.

Words cannot express how much I adore this take on one of our favorite childhood stories.

It was definitely worth the read.

I love the article, and it’s absolutely fantastic that reading this has encouraged me to think critically about Peter Pan as a character and the act of not making a decision. Fantastic writing and great analysis; I’ll definitely be reading The Artifice regularly.

I’d like to point out though, that not all writing is about making strong characters, and that often in reality we fall short of making our own decisions when stuck in binaries such as Peter’s final choice. External forces influence our decisions often more than we’d like to admit, and it doesn’t sound like, based on the story, that Peter has been placed in situations that would force him to make those types of decisive choices, accepting responsibility for the damage he’d possibly do to his life by foregoing one option permanently. If it wouldn’t be in Peter’s character to make the choice, wouldn’t it feel like authorial intrusion/morality if Peter made a decision one way or the other?

It’s funny that I found this article today, because I just thought of a similar situation while playing the narrative game Emily is Away. We often think of these types of decisions as massively pivotal, but what if they’re not as significant as we think? And what if making the pivotal decision doesn’t really save us?

Fantastic article! Beautifully written. I think it is interesting plot-wise that the choice remains, as you say, conspicuously unchosen, hanging in the balance in some respects. The comparison to college grads is a good one, as I have been feeling like this a lot, having finished a second degree a few months ago!

Pain is a great teacher. The trick is to learn from pain, instead of letting it scar us forever. The past can hurt, as Rafiki says.

I’ve wanted to read this book for a very long time. The problem was that I couldn’t find the right version to put on hold at the library. There are so many abridged editions, or children’s versions, etc. that I just couldn’t find the “original” book.

This was the most emotionally devistating children’s book I’ve read since Number the Stars back in grade school. It’s really a terribly clever and funny little book.

I’m not sure what to make of Peter Pan.

I think people get the wrong impression of Peter Pan from the Disney film… He’s not a smiley hero who enjoys adventures and laughter and fun. He’s a severely disturbed, selfish boy who has no qualms about killing and kidnapping.

Think about it… Children, by nature, are inherantly self-centered and self-serving. If we were allowed to stay children forever, we would never grow to learn things like love, patience, morality… I mean – think back to when you were a kid. You had no qualms about hurting another kid because they took something that belonged to you, or even something you wanted to belong to you. You didn’t worry about taking the last jelly bean, because you didn’t concern yourself with the feelings of others… What is one of the first words a toddler learns? “Mine”.

Essentially, Peter is trapped in this embodiment of immaturity. Everything to him is a game, because he doesn’t have the capacity to see otherwise. Even death. What does he say when Hook is about to kill him? “To die would be an awfully big adventure.” When faced with his own mortality, he still can’t be made to behave in any way but with childish abandon.

It’s not such a huge jump then.

The good guy wins in the end.

Responsibility is each individuals part to make the whole team a success…

I always saw Peter Pan as a little dark. Even at a young age I would never leave my family for a magical land. Just because it’s magic doesn’t mean it’s good.

Children’s stories are rarely examined under such a critical lens, so I really enjoyed reading this article. I’m really intrigued to read more of Chesterton’s work. The consequences of choice in children’s stories and fairy tales are so rarely considered, I think, because the ending is often a “happily ever after” or something along those lines, and we as readers don’t get to see those choices play out.

This is such a compelling and interesting article. All of your points are very thought provoking, and it was such a joy to read! It makes sense that the choices authors force – or don’t force – their characters to make that reveal the characters’ personalities, and ultimately their flaws. It’s a very useful tool for authors to use. So for Peter to not make a definitive choice only shows the flaw in his personality. He is a child, and children can be very indecisive at times. They can be stubborn and determined, too, which Peter demonstrates by not wanting to grow up. At least that is what I’ve gathered. Anyways, thank you for writing such a beautiful piece!

Peter reminds me a lot of a boy named Hugo in The Adventures Of Hugo Cabret. they are both ignorant so they would go perfectly together.

I thought I was going to love PP, but I didn’t. I was expecting magic and other fanciful things, but it was mostly violence, brutishness, and malevolent mischief.

The story of Peter Pan will always have a special place in my heart. I started with Disney’s movie and knew it by heart before I was five–that is, as long as I can remember. I didn’t read the true story until a few years ago. I love it. I cannot express how much I love it. Peter Pan is perfect.

With the great power comes great responsibilities.

Growing old is mandatory.

Growing up is optional.

Everyone has to grow up at some point.

Thus the term “Peter Pan Syndrome”.

To me, the story illustrates very much how JM Barrie (and a lot of other men) expect to be looked after throughout their lives without any commitment on their part.

Excellent analysis of a fascinating concept. I absolutely love how you go about it and explore so many different facets of the problem of making decisions, and groing old in Peter Pan, all grounded in solid sources. Good job!

While your analysis is interesting, I think you miss the point of the story. Peter Pan wanted Wendy as a mother, not a wife or girlfriend. If she had chosen to stay in Neverland, she would have been no more to him than a maid while he played with his mermaids, his fairy, and his Indian princess. He liked her good time companionship, but I never saw any indication that his fondness for her was so sincere as to create the need for a choice. It was Wendy who needed to make a choice. Would she chase the carefree life with Peter or grow up to be the mother Peter wanted her to be. It is not Peter’s character, though it be the titular one, that is the dynamic one. She was determined to grow up and he was determined not to grow up. Are there not many such relationships everyday in every age?

Even when I was a very small child I recognized this and I have always disliked the story just for that reason (and I was only familiar with the Disney version). The BOYS go to Neverland, a magical place of fantasy & magic, and get to roughhouse, have fun, & go on adventures! The GIRL goes to Neverland, a magical place of fantasy & magic, and gets to….be the @%&!# SERVANT for all those carefree little boys! And apparently just loves doing it!

As an active little girl who dreamed of pirates and mermaids and adventures, this absolutely infuriated me. I thought Peter Pan was a jerk, and all the women in his life got short shrift.

I just couldn’t fathom why anyone thought it was such a great story, or how no one could see what was glaringly obvious to me, at only six or seven years of age (well, I do always say I was born a feminist, haha.)

To this day (and I’m now 50) I cannot stand men who expect their female partners to be their mother.

I had no idea that I would like Peter Pan so much. It’s sort of creeps into the background of growing up, and then you don’t really think much of it.

Growing up is not all it’s cracked up to be.

Eventually you have to grow up, whether you want to or not, but as long as you retain that inner child, all will be well.

It’s a metaphor… Time chases us all.

The book actually suggest that “being stuck” as a child forever, like Peter, makes you incomplete and unhappy.

Really interesting read. Something else to consider in terms of “Heartlessness” is the moral ambiguity of Peter in the book. I haven’t read the original in its entirety, but I clearly remember on the trip to Neverland, it is said that “He always waited till the last moment, and you felt it was his cleverness that interested him and not the saving of human life…there was always the possibility that the next time you fell he would let you go.”

The ‘real” Peter Pan, or at least the boy the character was named after, killed himself when he was older because he was fed up with being associated with the book and his brother, the one whose spirit the character was most like, killed himself as part of a lover’s pact, I don’t doubt that there are a lot of dark shadows surrounding this tale.

Peter pan is like the undying child that everybody has inside. this isn’t a story with a moral, the kind that teaches you not to speak to strangers or stuff like that, it’s just a portrait of the spirit of youth that keeps coming around once in a while. that’s why it is ciclical and ends with the same scene as it starts.

Sometimes we got to see the world like children.n don’t give children too much stress.let them take their own time to grow up.

All a game.

Peter never wanted to grow up, but Wendy did. I think she realized that fun and games and getting away from reality is nice, but you can’t just stop your life. One day, you have to grow up whether you like it or not. It’s inevitable. It kind of reminds me of Tuck Everlasting, where the boy lived forever, but she didn’t. She wanted to grow up and believed living young forever really living.

This was very interesting to read. It’s true how a character’s decision leads to growth and development. And I do agree that by Peter not making a decision, he will ultimately stay the same. But that’s the thing, isn’t it? The story of “Peter Pan” is about a boy who never ages and maintains his childlikeness. So isn’t it fitting that Peter never changes who he is as a person? That he never develops or grows more as a human being?

As an adult everybody will always long for those fun and careless days, but when you don’t grow up, you will never experience life in full.

While we all get older… we don’t have to give up the beauty of being young.

His immortality in living forever is his own downfall and curse I believe to be unable to make any grown-up choice which is why the compromise suited his character so perfectly. But I believe it’s more than that. I feel like at times we are all Wendy and have our own Peter-Pan within each of us. There is always that turning point where we decide and make a choice that ultimately determines our purpose and passions to learn and grow. It is the significant turning point from childhood to adulthood. Once we make that adult decision the Peter-Pan will flea but live on through generations and generations. It is important for childhood development but a deception for eternity.

I’d never thought of Mrs. Darling’s offer of compromise as stifling the growth and power of Peter’s character before, but it makes total sense. Peter exists in extremes and boldness and at the will of no adult, so submitting his power to a grown-up, especially over something he feels passionately about, is quite unlike him. At the same time, because he is a child and typically children do not have or want to make difficult decisions, it would make sense for him to lend the choice to an adult. Of course, that logic stands for “normal” children, which Peter Pan certainly is not. Maybe I have juts talked myself into the concluding thesis after all LOL

A really satisfying walk-thru of Barrie’s play. Like a lot of readers, I think, I sort of thought of the ending as maybe beside the point, a punt that keeps the dream alive. But I think you’ve done a really good job exploring the other way of seeing it.

You briefly mention what I think is a very important point – that he has no parental figure to help him develop and grow as a human being. Generally, children need to be taught empathy; most of them don’t come by it naturally. So in this regard, I think Barrie has painted a portrait of a very real example of what could happen to a child with no emotional guidance. I think this is what determines the decision-making (or lack thereof): no real sense of urgency, no understanding of the passage of time and its implications or cause and effect, a thoughtless lack of consideration for others’ feelings, and a petulant, stubborn insistence on getting one’s way. When looked at through Piaget’s cognitive stages of child development, Peter is stuck in the Pre-Operational Stage, which makes sense since he isn’t developing at a normal human’s rate; indeed, he isn’t developing at all.

personally, I am a young adult myself and I was never able to see myself as an adult as a child and am still unable to do so now. I personally, love the idea that you can be forever young, even if it is all in your head to an extent.

I’m currently reading Peter Pan, and found this article quite stimulating. The way you describe the dilemma almost makes me want to draw parallels between Peter Pan and Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince, where the presumed unaging protagonist does indeed make the choice to return to his own love.

I loved this analysis – I found that Peter Pan’s lack of making a choice has much to do with his willingness to remain a child as children use adults and parents to act as their own agency, what makes this story sad is Peter Pan’s inability to see the joy and growth in making tough decisions.

The discussion of Peter’s heartlessness is quite interesting, especially when we take into account that even when he makes flippant comments throughout the book, Wendy, John and Michael are affronted and slightly shocked. We could say that it is the absence of the adult figure in Peter’s life that makes him so emotionally stunted, and basically afraid of making a choice as great as whether or not he should take Wendy back, or stay with her. He can’t make the choice, he simply doesn’t have the emotional capacity to!

If it hurts to make a choice, then I think it is the right place for someone to be. It means that something is about to change the very course of your life, and whether it be two bad things, or two good things, in the life roadmap, you’re at a fork in the road. I think this sort of situation is vital in teaching someone, even myself at times, that it’s important to trust yourself with your own decisions, and as a lesson to not regret those decisions. Years from that moment in your life, when you look back, maybe you’ll regret it and maybe not but without it you wouldn’t be where you are.

This is such a compelling read! I agree the story could have been more interesting had Peter been forced to make a painful choice, though I will admit that not every great story features a main character who changes. Sometimes they stay the same, for the most part, and when done well for the right kind of narrative, this is alright. But now you have me wanting a version of Peter Pan where he is forced to make this choice. Spielberg’s Hook is an interesting take on Peter growing up.

I disagree with many comments here, especially those in which children are called selfish and not caring for the feelings of others. We don’t have to teach them love – they already know love. We have to not teach them selfishness, because that’s what we do, not them – children are not born selfish. We often do that by indulging them and putting them above ourselves, thinking that we are showing them love but instead encouraging them to believe they are the only one who deserves the best, and then we complain and say “children are selfish”. We do that not just with children but also with the adults of our age, all our lives through.

So I see no point in such an almost ‘black-white’ division saying that children are clueless about what life is and only an experienced adult who’s learnt the price of things through sacrifice and hard choices can be honoured.

Wake up, people, you separate yourselves from a child in you and try to justify the ‘burdens of serious life’ by blaming childhood for being heartless and stupid and selfishly naive. The story is not about the deceptive carelessness of immaturity or the evils of procrastinating when moving into adulthood. Frankly, we won’t ever know all the subtleness of what exactly Barrie had in mind. But what should be paid due attention to is how we force ourselves to believe that our lives are torn into pieces by the age marks causing us to label childhood, youth and so on as some flawed stages of some inevitable and painful evolution. It’s not life itself that makes our living hard or dull or full of sacrifices as soon as we grow up, it’s us! We are afraid, we believe we owe something to someone, we have no guts to live out our dreams and then we complain about being tired of living by some unexisting rules.

So, really, let’s leave the kids alone and take a look into ourselves to make sure that we are not stuck in that fear…

To this day, I am still intrigued by Peter Pan and I’m so happy to see an article analyzing more about his fascinating image. I can’t wait to read more from you! This was beautifully articulated.

Hi Allie! I’m an italian student and I’ve just discovered this your work and… wow! So good! Would be possible ask you more details to seek the original and full text of Chesterton’s article that you mentioned in?

Thank you so much again for this great discovery!

Hey there! I’m sorry for neglecting your comment for so long–my life has left little time for the Artifice. But, since I love spreading the greatness of Chesterton, here is a link to a PDF version. The essay is ina collection of his works called Generally Speaking, and is entitled “On Sentiment” and found on page 94 (it’s from a more obscure collection, so it’s a bit difficult to find. However, the collection is on Amazon, with many more of his wonderful essays): http://www.cse.dmu.ac.uk/~mward/gkc/books/Generally_Speaking_scan.pdf.

Hope that helps!

Essay available here:

https://archive.org/details/essaysformalinfo00scot

I always felt as though Wendy was almost defined by her ties to the normal world. Though Wendy would cease being Wendy as she aged, a Wendy that became a permanent resident of Wonderland would scarcely be Wendy either.

Beautifully written, and definitely compelling and thought-provoking. Every time an external opinion on the topic was outlined, this author flips the script and articulates the opposite opinion. At the end of this article, it was interesting the concept of how choice leads to a character’s growth, and that growth makes a compelling character. But I’d point out that maybe Pan’s choicelessness and lack of growth is in line with his tagline “the boy who wouldn’t grow up”.

Balanced and articulate. I like that you started with Chesterton, that really helped introduce the paradox of Peter’s choice.

I did want to read a little more about Wendy, and not just about the role she played for Peter but her role in the narrative as a character with choices of her own to make. Otherwise, loved the article. Thank you for sharing.

Surely letting someone else make the decisions for him whilst recognizing his own failings demonstrates a level of maturity.

Surely letting someone else make the decisions for him whilst recognizing his own failings demonstrates a level of maturity

Sentimentality is the key to understanding the ending. The yes and no decision of Peter to stay and not lose Wendy is glossed with bathos, but it is not an adult decision. As an adult, this decision is a trick, a fraud. As a child, this is the happy ending, the best of both worlds where Peter can have his cake and eat it too.

If a child is not ready to make a decision, and there is still time, what is the harm? If a final decision has not been made, Peter can choose again. And if he doesn’t, Wendy can decide how to respond.

Thank you for the reference to Chesterton, I read and enjoyed that essay.

This is an insightful article encompassing the breadth of authorship and the steps in which one become a successful writer.

Wonderful.

I always liked and disliked the Peter Pan story. I completely agree that Barrie could have done more with Peter’s character. The fact that he chooses to be “gay, innocent, and heartless” kicks him out of having a true life where even though there may be sad and unfair moments, he would know what it is to love someone else, whether it is a parent, girlfriend, or friend. Peter misses out on many of life’s good things by choosing to stay in Neverland, which makes his story all the more sadder and darker.

A perceptive essay. Still one of my favorite Disney movies, which began when it was first released.

In one sense, the story reminds one of the Edwardian Era, on the eve before World War I.