4 Renaissance Plays That Weren’t Written by Shakespeare

From the late sixteenth century to the closure of theatres in 1642, an extraordinary amount of brilliant plays were written and performed. To this day, plays such as Hamlet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Romeo and Juliet are performed around the world to adoring audiences. However, most people only know of Shakespeare, which is a shame because there were many other great English playwrights during this time. These writers are undeservedly overshadowed by Shakespeare’s massive output, even though a few of their plays influenced some of the Bard’s greatest creations. The following are four plays written between 1570 and 1642 from three awesome playwrights that deserve more recognition. If you are a Shakespeare nut who wants to read more plays like his, then hopefully this list will scratch that particular itch.

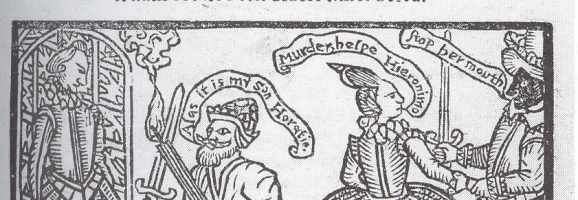

4. The Spanish Tragedy By Thomas Kyd

Written sometime in the late 1580s and first published in 1592, The Spanish Tragedy is not only an influential play, but also highly readable. The play takes place in the court of the Spanish King, following a battle between Spanish and Portugese forces. A peace is being negotiated by having the captured Portugese prince Balthazar marry the King’s niece Bel-Imperia. The plot of the play is complex as it weaves together romance and tragedy, culminating in a massive bloodbath at the very end. A father seeks revenge on the wicked killers of his son, the killers cover their tracks by manipulating their accomplices to kill each other and two lovers are separated by death. While the text is nowhere near as gruesome as Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, Kyd manages to insert quite a bit of violence for those who like their Renaissance Drama bloody.

The play helped create the Revenge Tragedy genre in English Theatre, which was heavily inspired by the works of the Roman dramatist Seneca The Younger and is an early forerunner of Hamlet. If you have seen or read Shakespeare’s play about the Danish Prince, then you will find many similarities between it and The Spanish Tragedy. Notably, both works feature a play-within-a-play as a plot device, albeit in Hamlet it is done to determine Claudius’ guilt, whereas in The Spanish Tragedy the device is used to enact retribution. The two plays also make use of ghosts who wish for revenge. More importantly, both main characters of each play doubt their need for vengeance at certain points. A lot of fun can be had trying to spot similarities to Hamlet when reading The Spanish Tragedy. It is also fascinating how Shakespeare used the same devices as Kyd in different ways to say different things. It is thought that Kyd may even have written a version of Hamlet before Shakespeare.

One of the most unique aspects of the play is the fact that the action is constantly observed on-stage by two invisible spectators. The first is Don Andrea, who was killed in the battle which preceded the play. He is accompanied by the physical manifestation of Revenge as they both watch the downfall of Andrea’s killer Balthazar. Don Andrea and Revenge remain on-stage throughout the entirety of the play, passively observing the other characters with the same privilege as the audience. At the end of each act they comment on what they have just seen, effectively serving the role of a chorus. Don Andrea is frequently frustrated by the misfortunes that befall his friends on-stage and the evil deeds of his enemies, while Revenge constantly pleads for patience on Andrea’s part.

Don Andrea is not the only character seeking vengeance. After his son’s murder in Act 2, Knight Marshal Hieronimo plans to expose and kill the murderers. The two guilty characters are Balthazar and Bel-Imperia’s brother Lorenzo. As Hieronimo determines their guilt and plots their downfall he delivers long soliloquies about his situation. The best one is given in Act 3 Scene 13, when Hieronimo debates with himself about whether he should go through with his revenge, or hope that Lorenzo and Balthazar receive their just desserts in time. The play overall forces the reader to question whether vigilantism is ever justified when the traditional justice system fails.

The play’s conclusion offers an ambiguous answer to this moral question. When all the supposed villains are killed, Don Andrea says to Revenge: ‘Then, sweet Revenge, do this at my request: / Let me be judge, and doom them to unrest.’ When declaring what each character’s punishment shall be, Andrea names the Duke of Castille, who is subjected to having vultures tear at his liver for all eternity, despite the fact he is a rather benign character who does no real wrong. This makes Don Andrea’s judgement questionable and one wonders whether the other condemned characters truly deserve the fate they are given.

By telling a sensational revenge tale, whilst questioning the very act of revenge, The Spanish Tragedy makes for an enjoyable, yet thought-provoking read.

3. Tamburlaine the Great Parts 1 and 2 By Christopher Marlowe

Like The Spanish Tragedy, Marlowe’s two parter is considered to be a highly influential play of the period. It was written around the same time as Kyd’s play, in fact he and Marlowe were living together. Both parts follow the titular Tamburlaine as he tries to conquer the world with his generals, his wife Zenocrate and eventually his sons. In Part 1, through success in battle and manipulation, Tamburlaine successfully conquers the Persians and the Turks, as well wooing Zenocrate, who is the daughter of the Egyptian Sultan . He then kills the King of Arabia and makes the Sultan of Egypt a tributray king out of love for Zenocrate, who begs Tamburlaine to spare her father. Part 1 ends with the two lovers getting married and Tamburlaine promising his new wife:

Egyptians, Moors, and men of Asia,

From Barbary unto the Western Indie,

Shall pay a yearly tribute to thy sire,

And from the bounds of Afric to the banks

Of Ganges shall his mighty arm extend.

Part 2 begins years later as Tamburlaine has three sons, who he wishes to be conquering warriors just like him. However, his eldest son Calyphas has no inclination to fight, much to Tamburlaine’s fury. Zenocrate dies in Act 2, marking Tamburlaine’s first real loss in the story. Meanwhile, Callapine, the son of the Turkish Emperor Bajazeth (who Tamburlaine had conquered in Part 1) swears revenge and musters an army to face Tamburlaine. He is defeated in the ensuing battle, but escapes to fight another day. Enraged by the fact that Calyphas decided to play cards rather than join in the battle, Tamburlaine slays his eldest son, before setting his sights on Bablylon. This leads to the most notorious moment in the story. After having the Governor of Babylon hung up by chains and shot at, Tamburlaine orders his men to burn copies of the Koran on-stage. Just before they burn he delivers this speech:

In vain, I see, men worship Mahomet.

My sword hath sent millions of Turks to hell,

Slew all his priests, his kinsmen, and his friends,

And yet I live untouched by Mahomet.

There is a God full of revenging wrath,

From whom the thunder and the lightning breaks,

Whose scourge I am, and him will I obey.

So, Casane, fling them in the fire.

He then goes on to say:

Now Mahomet, if thou have any power,

Come down thyself and work a miracle.

Thou art not worthy to be worshippèd

That suffers flames of fires to burn the writ

Wherein the sum of thy religion rests.

Tamburlaine ends the scene by saying ‘ Sickness or death can never conquer me’, only to be dying of illness in his next scene. The play ends with Tamburlaine’s death, where he urges his sons to continue his work by conquering the rest of the world.

Tamburlaine is an interesting exploration of morality and power. In a way, Tamburlaine is admirable because he comes from humble origins yet manages to succeed at wresting power from high-born kings through skill and cunning diplomacy. However, the malevolence he exhibits make Tamburlaine a morally despicable character.

Like The Spanish Tragedy, Tamburlaine The Great was one of the most popular plays of the period. It helped bring bombastic hyperbolic speech and character into style. The play was also highly sensational. Tamburlaine’s cruelty is not only displayed through his grand speeches, but also how he treats his enemies on-stage. In Part 1 he keeps the Turkish Emperor Bajazeth in a cage. In addition to the burning of the Koran in Part 2, Tamburlaine rides a chariot driven by the rulers he has defeated. These spectacular showcases of ruthlessness, combined with the grandiose dialogue make both parts highly entertaining to read and watch.

2. The Duchess of Malfi By John Webster

Unlike the last two plays, The Duchess of Malfi was written in the 17th century. It was first performed in 1614 and published in 1623. The plot revolves around the eponymous Duchess, who is a widow and told not to remarry by her brothers Ferdinand and the Cardinal. She defies them by secretly marrying her steward Antonio. Their marriage is discovered by the cynical Bosola, who spies for Ferdinand. Death, torture and revenge then ensue, resulting in one of the very best Revenge Tragedies.

Corruption is one of the major themes of the play, as references to poison and decay are frequently mentioned in the dialogue by the characters. Ferdinand and the Cardinal are obvious symbols of corruption as the former exhibits incestuous desire for his sister, while the latter has an affair with the married Julia. However, the Duchess herself can be seen to stand for corruption as her marriage to Antonio goes against societal traditions. Firstly, she is remarrying against her brothers’ wishes and secondly she is marrying someone below her station. The play therefore shows moral corruption as evil, while the corruption that goes against an unfair patriarchal society is viewed sympathetically.

One of the interesting questions that is posed to a modern audience is whether The Duchess of Malfi is a proto-feminist play. Arguments for this focus on the character of the Duchess. She is a rare case of a woman in society, who holds significant power, despite that power being threatened by her brothers. She goes against patriarchal society by taking a second husband, so she has agency in her sexual choices. Even though she is discovered and punished for this, it is meant to be tragic, rather than celebrated. On the other hand, every named female character in the play is brutally murdered before the end. In the play’s conclusion the surviving male characters (there aren’t many) come onstage and the Duchess’ son is declared her successor. This would suggest the restoration of patriarchal society. Also, in Act 2, Bosola mocks an old lady for wearing make-up and she notes how he is always ‘abusing women’. These exchanges between Bosola and the old lady are comedic, but his speech is misogynist, making the claim that The Duchess of Malfi is truly proto-feminist more tenuous. It is best to read the play and decide for yourself. Regardless of whether it is or not, the play is still a thrilling Revenge Tragedy that deserves attention.

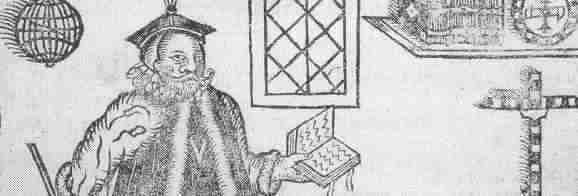

1. Doctor Faustus By Christopher Marlowe

Based on an old German legend, Doctor Faustus is reasonably well-known today, despite not being written by Shakespeare. It probably has the simplest plot out of the four featured in this article. The successful scholar Faustus grows bored with the traditional avenues of study and so turns to magic. He summons the devil Mephistopheles and sells his soul to Lucifer. In exchange, Faustus has Mephistopheles as a servant, along with all of his powers for 24 years. Once those 24 years are up, Faustus will be damned to hell. With these new-found powers, Faustus plays pranks on the Pope, impresses the Holy Roman Emperor and summons Helen of Troy, before being sent to hell for all eternity. The play also contains a comic side-plot, in which the clown Robin tries to use Faustus’ magic book, acting as a comedic mirror of Faustus himself.

Faustus is a difficult play to write about because there are two versions, both of which were printed after Marlowe’s death, making it impossible to truly identify a definitive version. The version published in 1604 is referred to as the A-Text, while the version printed in 1616 is called the B-Text. The latter is much longer and adds 676 lines, while omitting 36 lines from the A-Text. Several articles could be written on the multitude of differences between these two versions. To avoid confusion, this article will focus solely on the A-Text.

The play is incredibly ambiguous, which is probably why it is so enduring. It questions the nature of Hell itself. When summoned to Earth by Faustus, Mephistopheles delivers this speech:

Why, this is hell, nor am I out of it.

Think’st thou that I, who saw the face of God

And tasted the eternal joys of heaven,

Am not tormented with ten thousand hells

In being deprived of everlasting bliss?

Medieval art frequently portrayed Hell as a horrifically physical place. In his speech however, Mephistopheles suggests that Hell is also a state of existence; that the suffering of Hell is emotional , rather than just physical. This idea would make the speech disquieting enough, but the fact that it makes a devil sympathetic is equally troubling.

One of the stand-out moments of the play is when Faustus summons Helen of Troy’s spirit, so that he can woo her. The vague stage directions in this moment mean that there are countless ways to portray Helen. She could be played by a beautiful woman, or she could be a devil in disguise, she could even be imaginary, with Faustus talking to thin air. The scene best conveys the overarching theme of over-reaching ambition. Throughout the play, Faustus desires power and knowledge, even when it is out of reach. As Faustus says in an earlier scene, the spirits he summons are not ‘the true substantial bodies of those… which long since are consumed to dust.’ Therefore, Faustus will never be able to sleep with the true Helen, because it is beyond his powers to do so. This perfectly conveys how Faustus’ desires are not within his human ability to fulfill them.

Throughout the play, the audience is forced to question what is happening. There are probably two major questions at the centre of the play’s action though. The first is whether Faustus’ fate in Hell is sealed the moment he signs the contract with Lucifer, or whether he has the chance to repent until the very last moment. This question is rooted in the conflict between Catholic and Protestant ideologies, which frequently clashed throughout the 16th century. Some argue that Faustus is damned when he tries to woo the spirit of Helen. This is suggested by the line ‘Her lips suck forth my soul’.

The second major question is linked to the first: should we see Faustus as a tragic character who cannot escape his hellish destiny, or is he an idiot who throws away every chance he has at redemption? Whether you are religious or not, these questions of redemption and the irreversibility of destiny make Faustus a fascinating play. It makes you wonder about where humanity’s limits lie, about whether there is a point past redemption, whether human destiny is fixed and so much more. Doctor Faustus lingers in your mind long after it finishes, making it the best kind of Renaissance play.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Anyone that is a fan of Shakespeare’s ‘Titus Andronicus’ and ‘Hamlet’ need to read The Spanish Tragedy, as Shakes nicked at least one scene from this play and split it over the two (he didn’t even bother to hide it when he ‘borrowed’ from Marlowe’s ‘Jew of Malta’).

Is it just me or does Webster have a very strange fascination with taboo subjects?

The Duchess of Malfi is a play Shakespeare would write if he were just a little more sadistic and nonesensical. And tedious. lol

No, it’s not just you.

Great choice of plays. I actually bought Faustus for a module I was attending and expected to hate it. You know it is very good, and thanks to the notes on the facing page, quite understandable. One of those ‘on the list’ – I could tick off, and I know what people mean when they use the adjective “Faustian”.

Marlowe is one of the most overlooked writers of his era, it seems. Are his works even taught in schools anymore?

I read Tamburlaine in particular and loved it when I was younger.

I studied Faustus for a year in school. It’s what got me into Renaissance literature.

I don’t know if they teach Marlowe in the high schools, but I teach Doctor Faustus in my undergraduate Theatre History course. It’s always a lively discussion.

I too had to read Faustus for an OU course and was dreading it but I was pleasantly surprised! A bought the A text version. The notes on each page were really helpful as I wouldn’t have understood it without them. Am not sure I’d have read it if I didn’t have to but am glad I did.

Fantastic article! I studied a couple of Renaissance plays for uni last year, but from this list have only read Faustus. Thank you very much for the recommendations.

I watched a production of Dr. Faustus in Manchester a few years ago and absolutely loved it – and that was my introduction to Marlowe! I think that for some Shakespeare, Marlowe and Ben Jonson are thought of as the ‘big three’ of Renaissance theatre, I’ve also read parts of ‘The Spanish Tragedy’, however I’ve never heard of ‘The Duchess of Malfi’, it sounds interesting! Great article 😀

Excellent article. Thank you for writing it.

Christopher Marlowe might say that some more of Shakespeare’s titles should be included in this list of Renaissance plays not actually wrote by him, if certain conspiracy theories are to be believed!

I am taking an early modern class so I’m becoming familiar with Marlowe! I’m also about to start reading the Duchess of Malfi. I really enjoy the early modern period. Great article!

I firmly believe Shakespeare would not have been the playwright he was without Marlowe’s influence. Flippant though it sounds, thinking Shakespeare was the only renaissance playwright (in England alone) is the equivalent of thinking 60’s music begins and ends with The Beatles. Unless I’m much mistaken; aren’t Marlowe, Kyd and Webster all named candidates in the Shakespeare authorship question?

I have taken two Shakespeare classes (which by no means makes me an expert), but two in which have mentioned Marlowe and the Spanish Tragedy. I would love to learn more about the scope of other British playwrights. Shakespeare, in my opinion, is brilliant, but there is space in my heart to learn more about other sources.

I must congratulate you on such an awesome article. I really enjoyed it, seeing as I like Renaissance-related themes (mostly literature).

This is going to sound like a naive comment, but I recall reading this play from the mid-1500s called something along the lines of “How to be a Good Wife” in which this poor women gets harassed in every scene for “not being a good wife” because she is not obedient and pretty, from what I remember. I’m fairly certain the play was not satire, and it was generally awful.

If Marlowe hadn’t died at the age of 29 we might today consider his career greater even that of Shakespeare’s. It is interesting to note that until very recently, Marlowe’s ‘The Jew of Malta’ was rarely produced and the film version was only released in 2012 with very little public or critical interest and with no real celebrity interest in the cast. Shylock and Jessica in ‘Merchant’ have their predecessors in Barabas and Abigail in ‘Malta,’ and that the thematic content has clear overlaps. Both plays have been incredibly difficult to analyze and perform since and because of the Holocaust. People famously consider Shylock’s so-called “If you prick us, do we not bleed?” speech a point at which the audience sympathizes with the play’s villain. Marlowe’s play lacks such a speech, and his Jew is much a much more difficult character with whom modern audiences can sympathize. The truth is that in Elizabethan England, neither Shylock nor Barabas would have been considered sympathetic and the “If you prick us speech,” Shylock would have inspired more rage than pity or empathy.

I can happily say I’ve read 3 out of 4 of the plays on your list =].

Personally, I love “The Spanish Tragedy” so much more than “Hamlet.” I guess I have a stronger preference for direct action as opposed to “introspective thought” Also, I loved that the “play within the play” was used for murder as opposed to finding out the truth.

In regards to Faustus I definitely prefer the A-text. Specifically because it makes Faustus’ actions more ambiguous. Is he actually able to redeem himself? Isn’t he at fault for his actions? The B-text too easily places the blame on the Devil and creates a literal Hell that is not quite as fun to play around with than the more ambiguous Hell in the A-text.

Great article 🙂 thank you for bringing to light some other playwrights that deserve credit as much as the Bard.

Faustus is definitely a classic–how come there’s no mention of Ben Jonson? He was contemporaries with Shakespeare and was considered a brilliant satirist during and after his time. “Volpone” might be his most famous play.

Slightly ashamed to admit I’ve only read Faustus. BUT I did love it! I agree that Ben Jonson’s Volpone was a close second to some of these!

Excellent article, although I find it interesting that you chose so many pieces by Marlowe. The world of Renaissance literature outside of the Bard is quite diverse and I don’t think it gets enough credit. Thank you for your insight! Wonderful piece!

luv