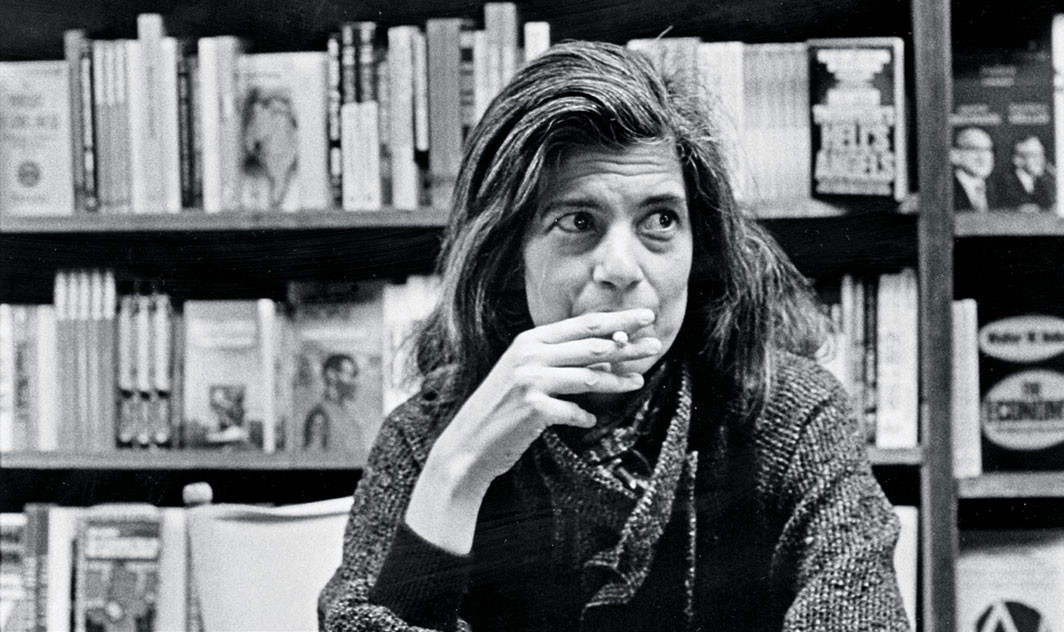

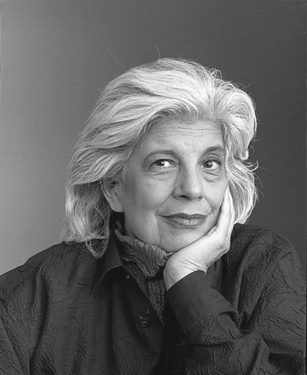

Susan Sontag and her love of photography

It’s been 42 years since Susan Sontag’s book On Photography was firstly published and, although the various forms of art, media, entertainment in general have experienced changes, the essence of photography as art and as mode of expression remained the same. In some ways, Sontag’s writing about photography serves as a prophecy of what society has become vis-à-vis both the concept of photography as an art and photography as an instrument or medium. She astutely makes cases for the various ways in which we can look at photography as an instrument; at the same time, with every word she uses to describe photographs and the mastery of photography, she betrays a love for photography as a form of art (“Time eventually positions most photographs, even the most amateurish, at the level of art” 1)

The book itself is a collection of 6 separate essays, each of them focusing in turn on social, cultural, historical and artistical aspects of photography. The subject of intermediality is approached on many occasions to illustrate the multiple disciplines which have benefited from the use of photography: art, history, medicine, politics (propaganda), criminal investigations, etc. Reading her analysis of works which are long past even to her, one can’t help but make a parallel between the timelines and the various media. Here we are analysing the written commentary, i.e. non-visual medium, which details the histories, trends and sensibilities of another medium which is extremely visual – photography. By reading Sontag’s appreciations on the photographers she mentions, one also learns the history of photography, as a medium, as a form of art and as technology. Indeed, her treatise is extensive and rich in detail. She selects a number of key photographers, all pivotal in establishing photography as a respected art. Geographically, she centres around the United States of America at the turn of the 20th century, which, with its ‘melting pot’ of cultures, served as an extraordinary subject for many artists willing to experiment.

Sontag bookends her collection of essays with a focus on the allegory known as Plato’s Cave, making us aware, from the start and at the end, of the role of photography as a projector or a simulator of reality. She gives a historical overview of the use of photography since its invention, looking at the camera as an instrument of expression used initially by Victorian societies and how this use has developed over time. Thus, an image starts with being a form of reality, “a mere image of the truth”, but then becomes memory, souvenir, and a way of connecting with both the past and other worlds. An image can transcend both time and space. Sontag also deftly analyses the cultural ramifications and the impact that came with the invention of such a powerful tool. The issue of agency is raised, Sontag pointing out that “The person who intervenes [in an event, i.e. the agent] cannot record; the person who is recording cannot intervene.” 2 Moreover, Sontag suggest that the camera can be both an extension of the photographer’s mind, their sexuality, of camera as phallus – Blow up, Peeping Tom, and an instrument, camera seen as weapon: “just aim, focus and shoot”. In this metaphor of camera as gun, Sontag goes further: just as the camera is a sublimation of the gun, to photograph someone is a sublimated murder – a soft murder, appropriate to a sad, frightened time.” 3 From camera as gun, to photography as instrument of morality is only a tiny leap and indeed Sontag reiterates the idea in the same chapter: “photographs cannot create a moral position, but they can reinforce one – and can help build a nascent one.” Sontag’s words on the oversaturation of photography in the 70s society seem almost prophetic for a 2010s society, suggesting that, more than with any other technical invention (except perhaps the Internet), photography is a dual medium, a complex tool that can have incredible artistic value, but it can also turn us into “image junkies”. Sontag points that “the knowledge gained through still photographs will always be some kind of sentimentalism, whether cynical or humanist […] a semblance of knowledge, a semblance of wisdom.” 4 Indeed, it seems that we have achieved and surpassed the saturation point described by Sontag as “the industrialisation of photography [which] permitted its rapid absorption into rational – that is, bureaucratic – ways of running society.” 5 We now have Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat and other social media platforms in which we see thousands of photographs every day. These help to sanitise our reality, anesthetise us to the atrocities that happen in the world as well as make us covet and fantasise about specific worlds, products, experiences that are advertised to us. The idea of nearness and isolation is poignantly illustrated in Sontag’s last chapter, The Image World, as she debates on the relationship between photography and the world, between the camera and the people taking photographs. In a time like today, where we get bombarded with photojournalistic images almost every minute of every day, through the usual social media channels, the “newness” of the news and the reality of the photograph lasts only a day, if that. The need for replenishment of information as well as distraction in the form of entertaining images is more acute than ever.

Sontag’s second essay, entitled Seen Through Photographs, Darkly raises questions of identity, artistry and humanity while experimenting with the concepts of beauty, grotesque, ugliness, all the while suggesting that the complexity of human nature cannot be encapsulated in one world. Artists will need a parallel world, which will be unearthed through their art. In this chapter, Sontag brings Diane Arbus and her body of work into focus, highlighting her preference for ordinary, yet extraordinary subjects. The way Sontag describes Arbus’ photography compels one to stop reading and go look for Arbus’ work. It is indicative of photography as an art form by excellence as well as a social commentary of America at specific point in history. The recurring theme in this chapter is both the damaging effect of labels and their boundaries. The author questions the definitions of beauty, normality, what is ugly and what can be perceived as conventionally beautiful or not, thus challenging the societal norms at the same time. Sontag uses Arbus’ work as illustrative of a deeper understanding between the artist and their work and her active choice of focusing on the less known individual types in society, the marginalised and the stigmatised. This is rightfully seen as a social commentary as well as a take on morality: art changes morals – that body of psychic custom and public sanctions that draws a vague boundary between what is emotionally and spontaneously intolerable and what is not.” 6 In refusing to accept the boundaries set up by the society, the artist looks to set up new rules, create new worlds and expose new truths.

“Arbus’s work expressed her turn against what was public (as she experienced it), conventional, safe, reassuring – and boring – in favour of what was private, hidden, ugly, dangerous and fascinating.” 7 What is still striking to us in 2019, is that the norms are still very difficult to break, the marginalised are still seen as ‘the other’, there are still societal rules, boundaries and labels, which make life difficult for those members of the society which do not conform to the standards of beauty or normality. However, there is more tolerance and fluidity, more acceptance and less conformity in society nowadays, which seems to have lessened the spirit of controversy diversity championed by artists such as Diane Arbus.

The third essay in the collection, Melancholy Objects, carries on the same path as the previous chapter of presenting the photographers as historians and anthropologists, as well as artists, looking for something to move them, to capture their attention and make them want to “memorialise” it. The notions of class divide as well as race are raised again, in a more detailed way, exemplified by photographers such as August Sander, A.C. Vroman, Roy Stryker and Berenice Abbott. The photographic trends continue to relate almost exclusively to the United States and it is almost surprising to see the breadth of subjects tackled through only one medium: class struggles, a disappearing race (the Native Americans), the emergence of photography as both a tool for advertising and a useful instrument in helping change some of the social injustices committed, all forming what Sontag calls “the human landscape”. Moreover, Sontag brings to the fore the idea of photography as “Surrealist abbreviation of history” 8. She also declares in this chapter that “America, that surreal country, is full of found objects. Our junk has become art. Our junk has become history.” 9 But, as she fervently likes to remind us, what makes photography art is the passage of time. What is interesting to note is how personal a photograph is. Sontag always refers back to this concept when discussing the medium of photography and what it means to us as humans, what it means to us as historians, social scientists, anthropologists or simply amateurs, curious about how life was well before we were born, before instant access to a camera and dozens of filters at the touch of a button. The idea of sentiment is always intertwined with the concept of photography: how it made us feel as viewers, how the photographers discuss it, explain it as creators, how the subjects felt or must have felt as the people immortalised on a square piece of paper. Even on a societal scale, the idea of photography has a deeper meaning, more than just a moment in a time long past. The photographic medium will always carry a message. That message will change, just as the society observing it will change, but the notion of photography as a carrier of message will remain. Sontag reiterates this when she ponders that “a photograph is only a fragment and with the passage of time its moorings come unstuck. It drifts away into a soft abstract pastness, open to any kind of reading.” 10 It remains up to us to read it. To further the point on photography as surrealist art, Sontag explains that “the rallying point of Surrealism [is], the photographer’s insistence that everything is real also implies that the real is not enough.” 11 Therefore, the photographer’s continuations to transform the present into past, or an alternate past reality will automatically render the present a banal reality, perhaps robbed of the passion which the photographer has dedicated to their art.

What Sontag achieves with her lengthy and passionate descriptions of famous early photographers, photography trends and the history of photography is to inspire one to go look for the photographs and photographers mentioned. Once this has been done, the comparison to what we consider photography nowadays is striking. As Sontag herself mentions, with the passing of time, any photograph becomes a work of art. More so, those taken by masters at their craft such as Steiglitz, Jacob Riis, Diane Arbus and few others, who manage to capture the essence of an era, a social class, a sentiment which remains ingrained on that specific piece of paper for all posterity to marvel at and wonder “was life really as portrayed in those pictures?” Sontag makes a point of highlighting that asking the question about the past is something not entirely straightforward. A photograph is a reproduction of a certain moment in time and we can only speculate on the conjectures which led to that moment. Comparing famous photographs of old to all the output we get bombarded with every day as we check Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, it may strike us that the reality of the old images is more relatable than those we see on the internet. With the advent of Photoshop, we are also warned to “take everything with a pinch of salt”, encouraged to double check the validity of an image that we find circulating online. The old photographs are sometimes easier to validate than the new ones, especially those by famous photographers. With few exceptions, they also seem to make a bolder statement. In the last 30 years or so there have been few photographs capturing the life of the contemporary individual the way Stieglitz, Dorothea Lange, Diane Arbus, Vroman, August Sander have done in the ever so distancing past. A point needs to be made that the contemporary individual doesn’t need to be “captured on camera” anymore. They will willingly broadcast moments of their lives, important or not, embellished (with extra aesthetical filters added for good measure) to be made as photogenic as possible. We are all hidden behind screens, projected onto screens, slimmed down, filtered through various applications, all aimed to make us look our best. Sontag’s point about capturing “what is beautiful” and not what is ugly has somehow lost its potency in a world where we are chiefly interested in what is beautiful, be it artificial or not. We might find it is artificial most of the time. We might also find that what is naturally beautiful becomes banal, just like the natural sunsets she speaks of, which we’ve all become so accustomed to. But what she meant by “beautiful”, I believe, was the essence of the human condition. The majority of the photographers mentioned in her essays focused, through their work, on documenting the lives of real people, “the famous men” (forgotten men) she references when she talks about the “documentary photography for losers”, Walker Evan’s photographic collection Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

In the chapter entitled The Heroism of Vision, Sontag once again analyses the idea of beauty as seen by various photographers of the early 20th Century. In this chapter she focuses on Edward Weston on and Paul Strand, and their body of work, noting that “Weston’s images, however admirable, however beautiful, have become less interesting to many people, while those taken by the mid-nineteenth century English and French primitive photographers and by Atget, for example, enthral more than ever” 12. Indeed, if one is not familiar with Edward Weston or Paul Strand, one would not fully understand the impact their work had on the future of photography. They, together with Alfred Stieglitz, who was offered both praise and scrutiny in Sontag’s previous chapters, are considered the fathers of modern photography as we know it today. The chapter dedicated to Weston and Strand would not be complete without a discussion about the Bauhaus School and the theories and aesthetics of modernity as well as the new emerging trends in both photography and painting. Sontag argues that “in the present historical mood of disenchantment one can make less and less sense out of the formalist’s notion of timeless beauty” 13 and her words have never sounded more prophetic. Even though what has in the past been considered beautiful (a nice shot of a sunset or sunrise), it has now become banal, so the artist must strive to find beauty through new and innovative means. Sontag reiterates: “the most enduring triumph of photography has been its aptitude for discovering beauty in the humble, the inane, the decrepit. At the very least the real has a pathos. And that pathos is – beauty […] Along with people who pretty themselves for the camera, the unattractive and the disaffected have been assigned their beauty.” 14 This can only be a strong argument in favour of regarding photography as a form of art. Moreover, both ideas of “beautifying” the subject and “naturalising” them or making them appear as close to reality as possible, have transcended the medium of photography. One feels compelled to draw parallels between the face portraits by Paul Strand and a carefully shot sequence from Luis Malle’s quasi noir melodrama Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (Lift to the Scaffold) – namely one where a desperate and love hungry Jeanne Moreau, wearing no makeup, walks aimlessly through the streets of Paris looking for her lover. The naturalness and beauty of that scene would serve as a precursor and inspiration for the French New Wave which soon followed.

The importance of text accompanying photography, context and captions is raised by Sontag, adding that commentary to a photograph or a collection of photographs is sometimes necessary in order to understand what we are seeing. She quotes Godard and Gorin, as they discuss Jane Fonda’s famous Vietnam photograph: “This photograph, like any photograph is physically mute. It talks through the text written beneath it.” 15 Indeed, the captions of a photography can make all the difference, particularly when referring to abstract photographs, which Edward Weston was the first master of.

In the chapter entitled Photographic Evangels Sontag returns to analysing concepts of reality in photography and addresses once again the issue of photography as art. She also brings technological achievements to the forefront of the debate, without which modern photography and photography in general wouldn’t be possible: “But as cameras get ever more sophisticated, more automated, more acute, some photographers are tempted to disarm themselves or to suggest that they are really not armed, and prefer to submit themselves to the limits imposed by a pre-modern camera technology – a cruder, less high-powered machine being thought to give more interesting or expressive results, to leave more room for the creative accident.” 16

Inadvertently touching on Baudrillard’s future theory of simulacrum, Sontag writes: “although no photograph is an original in the sense that a painting always is, there is a large qualitative difference between what could be called originals – prints made from the original negative at the time the picture was taken – and subsequent generations of the same photograph.” Despite there not being an original, the idea of authorship (with no visible signature, of course) is explored in detail in Sontag’s essay. She continues her argument by saying that “superseding the issue of whether photography is or is not an art is the fact that photography heralds (and creates) new ambitions for the arts. It is the prototype of the characteristic direction taken in our time by both the modernist high arts and the commercial arts: the transformation of arts into meta-arts or media.” 17 This statement sounds somewhat prophetic to what we’ve experienced since Sontag wrote her essay. The direction taken has somehow departed from what is known as art very much in the realm of media, mass media and more recently social media. The surge in photographs and collages which have evolved into what is now called memes is a significant mark of our times. While memes cannot be talked of as art (not yet), their importance is not to be understated, as their political, satirical messages carry a weight greater than that of the traditional art which can be found in a museum. The main reason for this is their accessibility as well as their influence with the younger generations. They also share a few characteristics with the post-modernist aesthetics and thus might be regarded as art form in due course.

Sontag beautifully bookends her collection of essays with references to Plato and the idea of reality, artifice and the role of photography as a medium to project reality. One can also look at the role of photography as a form of art capturing more than just reality: surrealism or simply faces, objects and moments that stirred feelings in a human being, prompting them to pick their camera and immortalise them. “Our ‘era’ does not prefer images to real things out of perversity, but partly in response to the ways in which the notion of what is real has been progressively complicated and weakened, one of the early ways being the criticism of reality as façade which arose among the enlightened middle classes in the last century.” 18

The book is completed with an appendix, a collection of quotes which capture the truth, the art and the sensibility of photography and of media. Among them sits one which perhaps resonates with us, as media historians, more than others:

“The media have substituted themselves for the older world. Even if we should wish to recover that older world, we can do it only by an intensive study of the ways in which the media have swallowed it.”

Marshall McLuhan

Susan Sontag’s work on photography and film philosophy remains seminal, at times prophetic, decades after being published, indicating that her insight into art and aesthetics remains relevant and influential. She is both an art historian and philosopher, with an enduring passion for photography which emanates from her writing.

Works Cited

- Susan Sontag – On Photography (1977, Penguin Books), p 21 ↩

- Susan Sontag – On Photography (1977, Penguin Books), p 12 ↩

- Ibid. p 15. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid p 21. ↩

- Susan Sontag – On Photography (1977, Penguin Books), p 41 ↩

- Ibid. p. 45 ↩

- Susan Sontag – On Photography (1977, Penguin Books), p 68 ↩

- Ibid. p. 69 ↩

- Ibid. p 71 ↩

- Ibid. p 80 ↩

- Susan Sontag – On Photography (1977, Penguin Books), p 101 ↩

- Susan Sontag – On Photography (1977, Penguin Books), p 102 ↩

- Ibid. p 102-103 ↩

- Ibid p. 108 ↩

- Susan Sontag – On Photography (1977, Penguin Books), p 124 ↩

- Susan Sontag – On Photography (1977, Penguin Books), p. 149 ↩

- Ibid p 160 ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Thank you for this piece. Like probably every queer girl who was obnoxiously pretentious as a high schooler i have a huge crush on susan sontag and honestly if she said something i disagreed with i am more likely than not to be like ‘wow she is right and i was just too dumb to see it before!’.

Thanks for reading. I think she was a fascinating essayist and philosopher.

She makes some really fascinating arguments about how the constant bombardment of images changes the way we view reality.

I agree. And I believe this is what’s happening with our society today.

Lovely take on her work. She has so many ideas and thoughts in her essays that I will probably be reading the book several times throughout my life. I am sure that I will learn something more from it every single time I read it.

Couldn’t agree more. I love reading the same book at different times in my life. It’s always interesting to see if your understanding of it changes. For me, it usually does, which I believe is a sign that you yourself have changed. The question is: in what way.

i liked her essays, and they were insightful, but i wished i’d felt more… excited while reading them? also the language used in the arbus essay is kind of gross.

Interesting. I like an opposite opinion from mine. I felt quite excited when reading her work, like I wanted to know more about the things she’s talking about. How do you mean gross?

You know, experiencing this again via your analysis, it is interesting to see that Sontag’s views still hold water. She has clearly looked at a lot of pictures and given much though to the whole business of photographs

I find her quite intense, don’t you? I think she was quite an intense person who felt and thought deeply about a subject she tackled. That was my reading of her based on her writing.

An excellent book review – I have read that book and found her ideas are inspiring. For instance, the relation between a photo and its text. I also have experienced what is said by her that camera can be offensive. People when noticing that they are shot may have a feeling of under a gaze.

Love Susan. Mesmerising, provoking (especially for someone into taking pictures) and in many ways strikingly prophetic.

Sontag could have published at least a couple of these essays today (I’m thinking In Plato’s Cave and The Image World) and they would be just as relevant now as they were forty years ago.

Do not hate me, but, I thought it was terrible, overly and unnecessarily complicated, and overall boring. I fell asleep reading it every time I opened it.

I really enjoyed Ch. 2 that focuses heavily on the work of Diane Arbus. I had just learned about Arbus in a class on American photography, so it was awesome to learn more.

One of the best books I’ve ever read about photography and history altogether. I only had to use one chapter to do my homework but ended up reading the whole book since it’s very interesting and so well written.

YES! Susan Sontag is one of the few nonfiction writers– a list to which I’ll add Walter Benjamin and Roland Barthes– who can simultaneously be intellectually provocative as all hell while still crafting gorgeous prose.

As an aspiring photographer who wants to capture responsibly and not just instinctively, her work is like a religion.

An excellent article. Refreshing, challenging and educational. Thank you for the decent read.

This book was a must read at the art academy for the department of photography at my university.

That is a tendency on most institutions and programs about that subject.

Great article. Sontag’s essays are perhaps even relevant today than when they were originally published.

Interested to learn more about how artists are making their own meaning out of photos traditionally used to oppress/exclude groups of people.

I get it. Susan Sontag was clearly a brilliant woman, but man did she suck at conveying her ideas & information in a way that’s even remotely accessible or palatable to normal human beings.

I agree that her style is quite unconventional, but I think that’s what makes her stand out.

Yeah, it makes you think deeply about how photography and the transferred experience of “being somewhere/sometime else” – transported in time or space or both.

I have heard Susan Sontag’s name before many times, but I was never sure what exactly she is known for. Thanks for covering this – I have already ordered my copy of her book.

Excellent. Let us know what you think once you’ve read it.

Melancholy Objects and The Image-World are the bomb.

Seems to be so many ideas and fragments in the book, and a great challenge to anyone who thinks about photography. You did a good job analysing it.

Thank you. And thank you for reading.

She taught me a lot, especially about the subtleties of picture taking and the psychology (and anthropology) behind it.

Her prose is incisive, and when I read it, I feel smarter, for having in my mind her ideas as if they were my own.

I wish I had Susan Sontag’s mind or eyes for that matter.

Intrigued by Sontag’s interests in China in the last chapter!

Thanks for the read. It continues to be relevant today, perhaps more than ever with the digital photography revolution well underway.

I read her book when I was 17 or 18 and it changed the way I looked at photography and art. I was just entering college as a photography major so it had a big influence on me.

I read Susan Sontag’s piece “An Argument About Beauty” for LBST 112, where she mentions photography at the end. Didn’t know how heavily she was into it, though.

If there ever was a book that requires skimming it’s this one.

Scary, how accurate some of Susan Sontag’s opinion are still totally up to date (instagram!!) over forty years later.

Her idea that every photo is a memento mori is so shatteringly, tragically true.

This makes me miss photography.

I will never look at a photograph the same way again.

Susan’s meditations on photography are thought-provoking and curious.

As an amateur who pursues photography as an occasional hobby, it was really interesting to read this piece. It served to widen my perspective.(pun intended)

That photo captioned “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men” is not from “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.”

Great piece!

This was a great reading!

Author’s fondness for -ly adverbs is off-putting.

Author’s habit words include “as” and shouldn’t.

Suggest author consult “Self-Editing for Fiction Writers” 2nd ed.

This piece was a wonderful summary of Sontag’s important On Photography. As the author indicates, her ideas are still relevant in the digital age. Sontag herself is an interesting figure, too; very much a product of the early sixties cult of the engaged intellectual.

I teach a class on Sontag and I intend on using Dani CouCou’s essay as assigned reading.

Thank you, that is quite a compliment. I have had great pleasure in studying her and writing about her and I’m glad you agree that her ideas are still relevant in the digital age. She should be a more well-known thinker.

thank you!

Dani

A very in depth review (Book Review) as it were, and first, I strongly recommend “On Photography” for those serious about delving into the intricacies between photography and the philosophy of photography: here Sontag focuses on the unique characteristics within the photograph and the conflicts born from (initial reactions) of the inherent mind-independence of photography, and an equal group of skeptics that are steadfast in their quest to prove photography’s mind-dependent (artistic) features. A must read for every student of photography, as well as patrons of the arts.

Lance A. Lewin – Photographer/Instructor/Lecturer

Georgia USA

Susan Sontag is such an interesting subject! I enjoyed your analysis of her essays. Both her writing and her photography are truly phenomenal.

Thanks for this close reading of Sontag’s close reading of photographs. I always wonder how her relationship with Annie Leibovitz affected her perspective.