Themes in The Book Thief

The Book Thief is a book written by the Australian author Markus Zusak and published in 2005. The story takes place in Germany around and during WWII. Guided by an original narrator, Death himself, we follow Liesel Meminger, a young orphan girl placed in foster care, nicknamed “the book thief” by Death. Here is how “[our] devoted Narrator” teases the story in the Prologue:

“It’s a small story really, about, among other things:

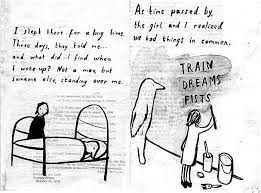

* A girl

* Some words

*An accordionist

* Some fanatical Germans

* A Jewish fist fighter

* And quite a lot of thievery.

I [Death] saw the Book Thief three times”

Through the many characters the reader meets along the pages, and the complex historical context in which they live, The Book Thief tackles many different themes, but they can be sumed up around three major notions: Death, Humanity, and Books. Those themes are, first of all, cleverly tackled, in a way that often subverts the reader’s expectations and goes behind prejudices, and, secondly, they are deeply linked to a constant reflection around the power of words and literature. Let’s analyze why and how.

Death

Death is a constant in The Book Thief, not only because the action takes place during WWII, and Liesel crosses path with Death three times, but also because Death itself is the narrator. (And what a narrator, as it will be shown throughout this article!) Death introduces himself in a Prologue written in the first-person. Plus, even though the majority of the story is told from an omniscient point of view and in the third person, Death comments Liesel’s story, adding context through flashbacks, teasing through flash-forwards, and digressing in bold sidebars. Death shapes, in more than one way, the book thief’s story.

In The Book Thief, the majority of the characters are marked by the death of loved ones, and by the guilt to have outlived them. When the reader first meets her, in the train that leads her to Hans and Rosa Hubermann’s place in the suburb of Munich, Liesel is confronted to death for the first time, as her younger brother dies in her arm. This tragic event is what pushes her to steal her first book: A Twelve-Step Guide to Grave-Digging Success, even though, at the time, she doesn’t know how to read. This tragic event also haunts her for a long time. Indeed, she has terrible recurring nightmares about her dead brother:

“She would wake up swimming in her bed, screaming, and drowning in the flood of sheets. On the other side of the room, the bed that was meant for her brother floated boat-like in the darkness.”

In the same way, Max feels guilty about the family he left behind, a family assumed killed or deported. As he arrives at the Hubermann’s place, exhausted and starving, he can’t stop apologizing in a “pitiful” way. Like Liesel, nightmares are haunting him. Death and guilt are haunting him:

“He [Max] wanted to walk out—Lord, how he wanted to (or at least he wanted to want to)—but he knew he wouldn’t. It was much the same as the way he left his family in Stuttgart, under a veil of fabricated loyalty.

To live.

Living was living.

The price was guilt and shame.”

Then, there is the mayor’s wife, Ilsa Hermann. She is grieving for her son, who died in Russia during the First World War. Her son’s death broke her:

“The point is, Ilsa Hermann had decided to make suffering her triumph. When it refused to let go of her, she succumbed to it. She embraced it.”

These are not the only ones whose loved ones have been ripped away, of course, but these three characters manage to overcome their grief and guilt. However, and the book shows it in a very clever way, it is not an easy nor smooth road. This process takes time and is full of forth and back. The peace they find is never to take for granted. There are relapses. There are deadlocks. There are obstacles. For instance, when Liesel comes back to the Hermann’s library, after tearing one of Ilsa’s book out of anger, she can’t bring herself to knock on the front door, and, on the way back, she feels her brother’s ghost, his disappointment, her newfound guilt.

Despite everything, what helps those characters heal is the bond they form with each other – and at the base of that bond are books. The first thing Liesel notices, when she brings Max food, is the book he carries. A few weeks later, Max offers Liesel a home-made book for her birthday, the same way he leaves her a book when he leaves. During his time in the Hubermann’s basement, Liesel brings him newspapers, so he can do crosswords. She reads with him, and to him when he falls sick. Ilsa and Liesel also bond and heal through books, and words, as Ilsa begins to invite Liesel in her library.

Liesel slowly discovers the loss behind Ilsa’s constant sadness, thanks to talks around the books Liesel borrows, skims, reads. At some point, the young girl feels “at home” in the mayor’s library, “among the mayor’s books of every color and description, with their silver and gold lettering.” She can “smell the pages.” She can “almost taste the words as they [stack] up around her.” Even when anger comes along, and Liesel begins stealing, Ilsa and her keep talking through letters, left in the library. Finally, when they make amends, the mayor’s wife jokes on whether she should use the door or the window, and she smiles, “for the first time in a long time.”

For those three characters words and books paved the way to others, to forgiveness, to peace. They soothe, at least in a way, the hole Death has dug in their heart.

But in The Book Thief, though, Death isn’t the ultimate villain. He is the one telling, reading the book thief’s story, and, as strange as that might be at first, we come to sympathize with him. Death becomes an actual character, a character that could come from a Greek tragedy. Just like Greek heroes, Death can’t escape his fate. He hates his “job”. Right from the beginning, he puts forward his need for a vacation – a need that was especially strong during WWII – and such a plea is reaffirmed throughout the book. But he can’t put his metaphorical scythe down, he can’t just quit, he has to keep collecting souls. He has to, though it is not of his own accord. He is as trapped as any other human, by his own nature. Many extracts could illustrate that, here is two:

“I [Death] am not violent. I am not malicious. I am a result.”

“And then. There is death.

Making his way through all of it.

On the surface: unflappable, unwavering.

Below: unnerved, untied, and undone.”

This original stance also leads to thoughts about war and its atrocities. Once again, Death takes a step back, and contemplates on his own prison:

“Death’s Diary: 1942.

It was a year for the ages, like 79, like 1346, to just name a few. Forget the scythe, God damn it, I needed a broom or a mop. And I needed a holiday.

[…]

They say that war is death’s best friend, but I must offer you a different point of view on that one. To me, war is like the new boss who expects the impossible. He stands over your shoulder repeating one thing, incessantly. ‘Get it done, get it done’. So you work harder. You get the job done. The boss however, does not thank you. He asks for more.”

The reader also sees how taking some particularly bright souls reaps Death’s heart:

“On many counts, taking [spoiler] was robbery.

[…]

Yes, I know it.

In the darkness of my dark-beating heart, I know.

You see?

Even death has a heart.”

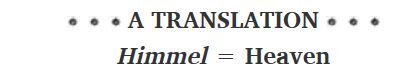

One literary device that may sum it up pretty well is the use of German in this English-written book. This device may be interpreted in several ways, as we will see, but here, let’s focus especially on the German words our narrator translates for us in sidebars, like this one:

Death speaks English and can translate German. By analogy, he speaks and can translate any language. Therefore, it can be a metaphor for his universality and timelessness. Death is also more powerful than any human, as, contrary to him, no man can be fluent in all the languages ever spoken. Yet, Death still is a “result”: in a way, he depends on mankind, he is the result of mankind’s existence and actions, the same way languages are. Plus, the fact that Death bothers to learn German, to speak German and to translate it for us, shows a more caring, human, vulnerable, side of him.

Without sugarcoating Death, such a narrative and writing style – the first-person narrator, its original status, the sweet irony, the poetry of some sentences, the intimate and conversational tone – give us distance on how we approach things.

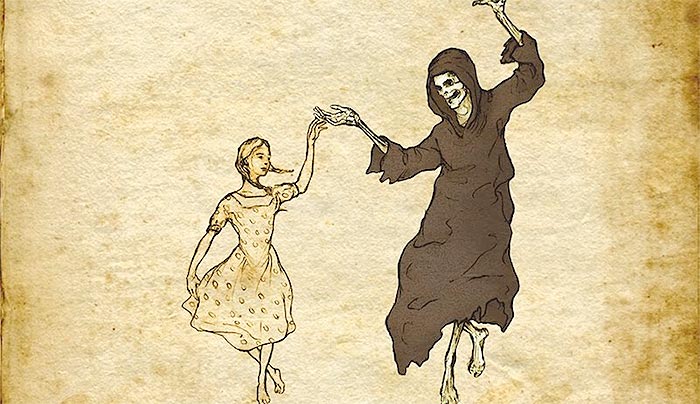

“ ***A SMALL PIECE OF TRUTH ***

I do not carry a sickle or scythe.

I only wear a hooded black robe when it’s cold.

And I don’t have those skull-like facial features you seem to enjoy pinning on me from a distance.

You want to know what I truly look like? I’ll help you out.

Find yourself a mirror while I continue.”

And that leads us to our second theme.

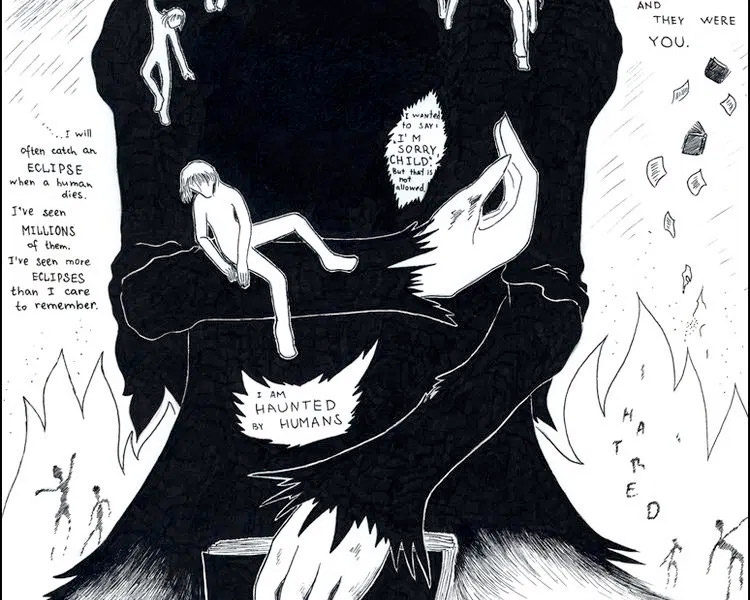

Humans and humanity

“Humans” is the last word of the novel, as Death reveals to an old Liesel, one last secret: “I am haunted by humans”. Humanity, Human Nature, and its complexity are at the center of The Book Thief. The novel highlights both the duality that marked that specific historical context and the duality and complexity within individuals themselves, regardless of the historical context.

Guided by our original narrator, the reader dives into the atrocity, into the unspeakable reality of the Nazi regime, and into the war it triggered. We see some faceless fanatics beat or kill innocents men, women, children just because of their religion, or their political believes. All of this is shown either through the eyes of Liesel, a young girl, or through the eyes of Death. The first point of view highlights the horror of it, while the second gives us a distanced and slightly ironic opinion, that stresses the madness and obliviousness in humans:

“It kills me sometimes, how people die”

“A small but noteworthy note. I’ve seen so many young men over the years who think they’re running at other young men. They are not. They are running at me [Death].”

We see acts of fear, envy, nastiness, anger. Out of anger, because the mayor dismissed Rosa, Liesel tores apart one of Ilsa’s books and begins to steal from her. Out of envy, and hunger, Rudy steals from a boy who was carrying food to the local priest. Out of childishness, Rudy and other kids, Liesel included, often make fun of Tommy Müller, because of his tics. Out of nastiness and lust for power, Franz Deutcher bullies Rudy during Hitler Youth sessions. We see the Hubermann family being ripped apart by political divergence, as Hans and his grown-up son don’t share the same convictions regarding Hitler and the Nazi party.

But we see acts of kindness, as well. The biggest one, is, of course, Hans and Rosa’s decision to hide Max, despite all the risks involved, not only for them but for Liesel as well. The decision isn’t easy for the couple. But Max’s father saved Hans’s life, back in France during WWI, and Hans made a promise to help his family.

We also see smaller acts of kindness, but, somehow, they are as no lesser than taking Max in. We see Rudy give a teddy bear to a dying pilot whose plane crashed near Molching. We see Ilsa kindly invite Liesel in the library. We see Rudy stand up for Tommy Müller during the Hitler Youth. We see Liesel read to calm everybody’s mind during an air raid. We see Rudy and Liesel, and Hans, give bread to Jews on their way to Dachau, despite the soldiers’ warnings and threats.

Acts of goodness – Hans giving bread to a Jew – are sometimes juxtaposed to acts of cruelty – a faceless soldier battering both Hans and the Jew as a punishment. Some symbolic actions – Rudy stealing bread and then giving it – are echoing in a mirror-like disposition throughout the book. As Death puts it, when he comments on Rudy’s thief:

“In years to come, he [Rudy] would be a giver of bread, not a stealer – proof again of the contradictory human being. So much good, so much evil. Just add water.”

In the end, that is what the novel points out: human complexity, duality, contradictions. Or, to quote Death, once again:

“ I’m always finding humans at their best and worst. I see their ugly and their beauty, and I wonder how the same thing can be both.”

In this historical turmoil that stresses both the kindness and the cruelty, the beauty and the ugliness of humans, the main characters are still kids and young teenagers. Despite the circumstances, they are not deprived, not entirely at least, of their childhood. Readers can relate to them, to their experiences, to their feelings and discoveries.

Their hope and energy shine and drive the whole book. Liesel, Rudy, as well as the other kids of Himmel Street regularly play soccer, and matches are as important as actual world championships. Rudy often brags about how he scored, and Liesel gently makes fun of him. Despite the risk and the cold, Liesel brings back some snow in the basement, and with Max, then Hans, and even Rosa, they end up building a snowman. From the moment they met to the one death do them apart, Rudy keeps asking Liesel for a kiss. If at first, it is a childish game, it ends up being a genuine wish, so much that even our narrator pleas Liesel to kiss him – “Kiss him, Liesel, kiss him.” – as they both stand in the old Steiner’s shop on Christmas day. Liesel, too, begins to grow deeper feelings for her best friend, as shown by her fluster when the boys are passing a medical exam, in the 58th chapter soberly called The Thought Of Rudy Naked. And, like many teenagers, especially ones with a big secret to carry, Liesel writes it down, in the diary Ilsa gives her.

That particular energy and innocence is shown through words, and especially Liesel ones. For instance, when Max asks her what is the weather like, outside, she answers: “The sky is blue today, Max, and there is a big long cloud, and it’s stretched out, like a rope. At the end of it, the sun is like a yellow hole.” It makes Max laugh, and it is better than the plain weather report he expected, or the one he could read in the newspaper Liesel brings him. Another example: when Liesel knocks on the mayor’s mansion for the first time “a bathrobe [answers] the door. Inside it, a woman.”. This is an almost poetic way to describe things, and it is also an illustration of how children may see things in a different way than adults do. Yet, it still carries a tremendous amount of truth. Ilsa Hermann is, indeed, drowning in her sorrow, hiding in her pain, masked by her suffering, the same way Liesel sees her drowning in her bathrobe, masked by it. Similarly, Death also uses a countless number of metaphors, analogies, and comparisons, to tell us the unspeakable, to make me feel it, beyond the sole, frozen words, to drag the reader away from the comfortable sofa on which they are reading the book thief’s story. Words, used in this almost poetic way, suit the childish innocence as much as the seriousness of Death. Therefore, they can carry, they can embody the human duality, contradiction, complexity. They embrace it and unite it, against all odds. They make one of beauty and ugliness, of innocence and gravity, of life and death. They celebrate human resilience. As Death, once again, says:

“It amazes me what humans can do, even when streams are flowing down their faces and they stagger on, coughing and searching, and finding.”

But we might already be impinging on our last theme, here.

Books, writing, and storytelling

As it was demonstrated in the last two parts, books, and words, are at the core of The Book Thief. But, here, let’s focus on the importance of books in their materiality, and everything it entails and symbolizes.

The story Death reads us is the book thief’s story, written by the book thief herself. When they both make amends, Ilsa offers Liesel a notebook for her to write on. Indeed, the older lady spotted Liesel’s writing skills, but also both her need and her entitlement to do so, to write her story.

“She [Ilsa] gave her [Liesel] a reason to write her own words, to see that words had also brought her to life. ‘Don’t punish yourself’, she [Liesel] heard her [Ilsa] say again, but there would be punishment and pain, and there would be happiness, too. That was writing.”

When Himmel Street is accidentally bombed, Liesel is writing her story in the basement, which is a highly symbolic place. Indeed, it is where she learned to read with Hans, learning new words and writing them on the walls. And that – her being in the basement, writing – literally saves her life.

As she exits from under the rubble, and contemplates the destruction and death with her notebook still in hand, she holds on to it, “she [holds] desperately on to the words that had saved her life.” The meaning is as metaphorical as it is literal. This book, full of her words, saved her from the bombing, the same way she saved The Shoulder Shrug from the flames during the celebrations for Hitler’s birthday years before – her second theft.

Books, and the words they carry, can physically affect people. They can hurt. Liesel hides The Shoulder Shrug in her jacket, and it burns her: “Smoke was rising out of Liesel’s collar. A necklace of sweat had formed around her throat. Beneath her shirt, a book was eating her up.”. Later, she physically tears a book apart, out of anger, and despair, and powerlessness:

“She tore a page from the book and ripped it in half.

Then a chapter.

Soon, there was nothing but scraps of words littered between her legs and all around her. The words. Why did they have to exist? Without them, there wouldn’t be any of this. Without words, the Führer was nothing. There would be no limping prisoners, no need for consolation or wordly tricks to make us feel better.

What good were the words?

She said it audibly now, to the orange-lit room. “What good are the words?”

Just when she has begun to understand and master words, and the power they give her – when she read to the frighten people of Himmel Street hiding in the bomb shelter, for instance – she is confronted to their dark side, to the evil they can produce.

But she also knows that hateful messages can be debunked, replaced, vanquished. Max, of all people, shows her how. Indeed, on two occasions, he paints over the pages of Mein Kampf. He physically erases the hateful words, and, as he writes stories for Liesel, he replaces them with hopeful and kind ones.

That is why, strengthen by those experiences, Liesel knows, when Ilsa offers her the notebook, that “there would be punishment and pain, and there would be happiness, too”, even if, of course, she can’t foresee what is about to happen. That is also why, during her last night in the Hubermann’s basement, she completes writing her story – entitled The Book Thief – with one final note:

“I have hated the words and I have loved them, and I hope I have made them right.”

Just like Max, when he wrote The Standover Man, writing all of it down allows Liesel to reflect on her past, on her own story, realizing Death’s forecast, but also Max’s. Indeed, in his second home-made book offered to Liesel, The Word Shaker, the young man writes:

“THE BEST word shakers were the ones who understood the true power of words. They were the ones who could climb the highest. One such word shaker was a small, skinny girl. She was renowned as the best word shaker of her region because she knew how powerless a person could be WITHOUT words.”

At the beginning of the novel, Liesel don’t know how to read, nor write. She “was the book thief without the words.” But she learns. To quote Death, once again: “the words were on their way, and when they arrived, Liesel would hold them in her hands like the clouds, and she would wring them out like the rain.” Words, through books, became her revenge on life. And so was stealing them, because “[w]hen life robs you, sometimes, you have to rob it back.” Books, at first, meant nothing to the young girl, then they begin to mean “something”, and they end up meaning “everything”.

That is why she holds “desperately” to her book when her world comes to an end. At some point though, in the chaos of the moment, Liesel’s notebook, Liesel’s story, Liesel’s Book Thief, The Book Thief, slips from her hands, joining the rubble. Nobody cares about it. Nobody except Death. It is the third time he sees Liesel. It is the third time he stops for her. He picks up The Book Thief. He keeps it. He reads it for himself. Then, he reads it to us.

The Book Thief – by Markus Zusak – is an embedded story, that entwines and reunites The Book Thief by Liesel Meminger, and Death’s commentary of The Book Thief. As mentioned before, Death comments the story, adds some details, and, sometimes forecasts or reveals what will happen later. Prolapses are a known literary device, but some of Death revelations are quite surprising. Our narrator doesn’t hesitate to unveil the tragic fate of some of our beloved characters. Rudy’s death, for instance, is announced half-way through the book, at the beginning of the fifth part. It makes sense, as Death has already read The Book Thief, and is, commenting accordingly. The interesting thing is how he justifies such a shocking revelation:

“Of course, I’m being rude. I’m spoiling the ending, not only of the entire book, but of this particular piece of it. I have given you two events in advance, because I don’t have much interest in building mystery. Mystery bores me. It chores me. I know what happens and so do you. It’s the machinations that wheel us there that aggravate, perplex, interest, and astound me. There are many things to think of. There is much story.”

That might be a piece of reading advice, as much as writing one. The stories themselves, the way characters evolve, grow, interact, what we learn from them, what we learn with them, matter more than the ending in itself. The author seems to cast a critical look on storytelling rules that may be taken for granted by some. He seems to be deconstructing the way we may see books, stories, and narrative arcs. Such a stance also leads to the legitimization of rereading. Therefore, it echoes with Liesel’s way of reading. As she doesn’t own a lot of books, she often rereads the same ones, and, yet, enjoys them just as much.

One final thought on the use of German in an English-written book, to finish. Maybe German was what suited the most the story and to the author? According to George Steiner – a Jewish philosopher, from an Austrian family who fled to France, and then to New-York in 1940 – the myth of Babel is not some divine punishment. On the contrary, it is a gift, a blessing. From then, language is a living entity, a world in itself, that unveils an aspect of reality. To Steiner, in Errata, An Examined Life: “our literatures are the children of Babel.” If translations are necessary, they are also very delicate. They take something from the original material, and, therefore, they have to add something to the source, to fix their “intrusion”. Multilingualism must be preserved, and, even encouraged, because it allows the mind to expand, to have access to many different worlds. Indeed, to G. Steiner:

“To speak a language is to inhabit, to construct, to record, a specific world-setting – a mundanity in the strong, etymological sense of the world.”

G.Steiner. Errata, An Examined Life, chapter VIII

Languages are also a way to stock memories. As Steiner writes:

“They preserve configuration of mores and institutions long past and almost indecipherable to the present.”

G.Steiner. Errata, An Examined Life, chapter VIII

Therefore, keeping German words and sentences in the text may give a glimpse, or, at least encourage readers to take a glimpse of another “world-setting”. It might warn and prevent against a linguistic dictatorship drift, or against an ethnocentric and reductive point of view. Keeping German words and sentences can also be a way for the author – Markus Zusak – to preserve, or even make more vivid, the memories and stories of his parents and grand-parents. Indeed, Markus Zusak comes from a German-Austrian family, who moved to Australia after the war, just like Liesel does. Indeed, in the book, Liesel moved to Sydney, Australia, where she lived a full life and died at an old age. From a young orphan girl who didn’t know how to read and write, she becomes fluent and literate in two languages, at least.

In the movie, she even has became a renowned writer, as shown by the many awards see in her office. In the movie final scene, we also see the pictures of her friends and family, showing, once again the importance of bonds with each other.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I thought the film was decent. The biggest criticism I had was the switch in languages. I would have either preferred them to speak in English (with their own accents) or German, but the swap seemed random. And although it appeared that anyone who was a Nazi spoke in German, it really wasn’t like that. There were plenty of Nazi’s who spoke in English with put on German accents.

The actually story is quite an interesting one because there are very few films which show that the holocaust was not just the targeting of Jews, and that the German communists were one of the first rounded up and sent to concentration camps

I haven’t seen the film in a long time, so I may be wrong, but in the French version I watched, I don’t remember any German accents, at least for the lead characters! If so, that is an interesting choice of dubbing! Concerning the swap, in the book, especially with Death explanation, I think German sentences and phrases truly add something to the story. In the film, it probably is less critical, as Death doesn’t comment on it. Plus it seems to me that, in movies taking place in a foreign country, inserting foreign words and sentences is a common device.

I’ve never understood why English-language films set in non-English speaking countries so often require actors to speak with a specific accent. If they’re already speaking in English, the audience will be suspending their disbelief for that anyway. In my opinion, making them speak English with a clearly foreign accent actually makes it seem less realistic than letting them speak any variety of standard English.

It’s even more annoying when it’s inconsistent – think Rooney Mara’s near-perfect Swedish accent vs Daniel Craig not even trying, in the Hollywood version of The girl with the dragon tattoo.

And then you’ve got cases like ‘Valkyrie’ where American/British actors speak in their normal voices but then their fellow conspirators – German actors, speaking English – talk in their natural accents and it all seems a hotchpotch.

Hollywood films bend over backwards to make a film’s mise-en-scène as perfect as can be…and then they muck up their hard fought sense of verisimilitude by having native characters speak to other native characters in their native country in English rather than the native language. The newscasts in the U.S. re-make of ‘The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo’ and their newscasters giving it some Swedish-accented English? Gah! The idea that they make things in English for marketing doesn’t hold much water as Hindi and Cantonese languages are more widely spoken in the world.

Give it a few decades and having non-native English speakers speak in English will be seen as anachronistic as bad back-projection or actors playing Othello with black make up all over their faces.

I think that people complaining about characters speaking English in films set in non-English-speaking countries ought to be careful what they wish for.

If this didn’t happen I suspect that we would not end up with the same number of such films, except with subtitled actors speaking the appropriate language, instead we would have no major international films set in non-English speaking countries at all.

We only have to look at the historic example of dubbed foreign-language films. Believe it or not, in the UK foreign films played routinely in the smallest local village fleapit cinema until about the end of the 1970s.

They were routinely mocked by everyone who would prefer to see a subtitled version – including me. However, when they did disappear, partly through being ridiculed to death, we didn’t get the subtitled version at the local picture house, we got none of them at all.

The only foreign films which still appeared in the UK were a relative handful of subtitled arthouse films playing arthouse cinemas – well away from most of the population.

Since then, generations of people have grown up believing that foreign cinema is all high brow and not for them. The likes of the dubbed Alain Delon or Jean-Paul Belmondo thrillers which provided an entry point for foreign films for many people just didn’t get distributed. Many people who had that introduction in a familiar setting would move on to subtitled films – eased into them by familiar actors and settings. Now for most people foreign films are doubly daunting, they just don’t bother and they have largely disappeared from mainstream television too.

Get rid of actors speaking English in non-English countries and there may be no large scale films set there at all.

I loved The Book Thief – it’s a brilliant and engaging read and, as such, on of my favourites. In fact, I have recommended it to many friends (and some of my students) and do not know a single person who was not swept swept along and moved by the story and it’s characters, so vividly drawn.

We read it in my book club, and not one of us was “swept along” in the described manner. It seemed like a very sad but rather predictable tale of the Nazi rise to power, with a slightly odd writing style. Incidentally, I alone knew that it was a “young adult” novel as I had done some research, there was nothing on the cover to suggest this.

It is, indeed, more of a “young adult” novel, even though, to me, many adults can enjoy it. Of course, it won’t affect you the same way depending on your age, depending on what you expect of the book, and, in a more general manner, depending on what you seek in your readings, what you expect of them, and what you already read (or haven’t read yet).

It is, indeed, an amazing book, and one of my favorite too! I had some teachers who recommended it, and, even when I had already read it, it always made me happy to see an adult talk about that book, and I often ended up reading it again after school!

Good analysis.

The Book Thief (the book) is interesting because it looks at Germany and the Nazis from a different perspective. I would suggest people read the book first before they see the film.

I agonised over the death of one of the characters. The innocence of this person transcended the character’s belief. On the other hand, the survivor is unexpected. It forces you to remember that even though there was unspeakable carnage, there were survivors and they have a tale to tell.

It is a deeply sorrowful but clever portrayal of the stupidity and sheeplike mentality of humanity and it asks young people to question what they are being shown when they are vulnerable. It also shows that, especially for the children, redemption is possible; that war is a waste of youthful potential. Death does not choose. Death is also powerless.

I feel you are inferring far too much of your feelings from the book in the film. For those who have not read it the film is rather emotionally barren.

Thank you, Craig!

I agree with you, I think the book is better than the movie – as it generally is. The book is powerful, nuanced, touching, heart-wrenching! Death’s portrayal and his comments are so clever! However, to me, the movie did a decent job, even if it wasn’t nearly as amazing as the actual book. In, some cases, a young who struggles with reading, for instance, could be encouraged to read the book, after seeing and enjoying the film.

Great help for my students tackling literary elements. THANK YOU.

My pleasure!

My husband is German, and the characters in the book – at least the events that happened to them – are actually are quite true to life per my German in-laws and their neighbors and friends. My 13 year-old, half-German daughter watched the film first, which…granted…isn’t all that great. But it did inspire her to read the book, to think a lot about history, tragedy, culpability, and her relationship to the above as a German citizen. It also helped her think about these questions more broadly, beyond the German context. And it led to several interesting dinner table discussions with our whole family.

I think the author, Markus Zusak, not only drew from his parents’ and grandparents’ stories but also did a lot of research, to be as truthful as possible. Your story seems to indicate that he did that well! I always find amazing how books (and art in general) can help us grow as individuals, connect with others, and think about some of our world’s past and present issues!

I still cry thinking about Rudy. He never got a kiss in his alive moment and this kid , I felt like he was my bestfriend and I lost him. We didn’t even meet but I lost him. It was such a hurtful feeling you know because he was the one I felt most welcomed with. I should just get over it.

Rudy is amazingly written, and his death is heart-wrenching, even for Death himself! Somehow, I think the fact that Death warns us of his fate in advance, make Rudy’s passing even more tragic and emotional. Well sometimes, there are books or characters you can’t get over, and, maybe that’s not such a bad thing, even if it hurts sometimes – if all of that makes any sense!

Who says you have to “get over it?” I don’t think there’s anything wrong with embracing fictional characters as friends, as people we identify with and can grieve over. Plus, if you’re going to grieve a character, Rudy fits the bill. I loved his sanguine personality and character arc. I think he, out of everyone, might have had the harshest “awakening” to the reality of war, the Nazi rise to power, and so forth. Check out his response to Jesse Owens, juxtaposed with his family and country’s responses.

This has been one of my favorite books for a few years now and I just love it so much! None of my friends have read this book, no matter how many times I recommended it to them, so I haven’t been able to discuss my thoughts and feelings about The Book Thief. But this is the book that made me love the historical fiction genre to the point where I am obsessed with anything historical fiction related.

It is one of my favorite books too! That is so frustrating when you recommend a book (or film, or TV show) to a friend, and they never read (or watch) it! Well, maybe here is a good place to discuss your thoughts and feelings about The Book Thief!

So sad that none of your friends have read it. I hate being the only one in my circle who knows about a great book. Personally, I wish it had been around when I was the protagonists’ age. I think Liesl would’ve been one of my heroes/soul sisters. I like how Zusak surprised me with her character; I expected her to be a classic, scholarly type. I absolutely cheered when she stole the book from the burning.

It’s a good book and movie directed at young adults, especially those who haven’t yet been acquainted with the atrocities. It’s a good lead-in for broaching the subject of the Holocaust, along with the Diary of Anne Frank and the story of Corrie Ten Boom.

I agree, but I think the themes The Book Thief tackles are even broader than that, it’s not just the Holocaust, but the entire period that stretches from the First World War to the end of the Second World War, with all the atrocities it contained.

The Diary of Anne Frank is very good too! I’ve never heard of the story of Corrie Ten Boom, thank you for the tip!

This book really impacted me as a child and your point about breaking storytelling rules is really interesting. I remember reading Death’s spoiler of the end a bit over halfway-through and regretted having seen it. Thought it would lessen the impact of the ending. But you phrase it really well considering history is history, it can’t be changed, and although we are aware of the atrocities that have occurred in the past, it’s those lives that are meaningful.

Thank you! I was shocked as well when I first read The Book Thief, but with time and with a few rereads, it begun to make sense to me! Plus, I think it doesn’t completely spoil the ending, even at the first reading. Personally, I couldn’t quite believe that the author chose to spoil its book half-way through the story! I thought there were gonna be some kind of twist, so I was still, in a way, surprised by the ending! And, indeed, I think the path the characters take is more important that end of the road in itself!

strong.

It is actually…not really about the Holocaust.

The Book Thief is about a lot of things, as tackles a lot of issues and atrocities that happened from the First World War to the end of the Second World War, so it encompasses the Holocaust, but, indeed, it is not centered on it, at least not like most books and novels about the Holocaust are. Tackling broader themes and issues allows, in my opinion, the book to deliver an even more timeless message. Some of the issues The Book Thief tackles are still very relevant in today’s societies.

That’s true, and was one of the things I liked about it too. There aren’t many war films that show the war from the perspective of ordinary, non-Jewish German families.

I quite enjoyed the file without knowing it was a children’s book. I think it stands alone as a fairly good film, not brilliant but I did stay to see it to the end which is always a good sign.

Now I’ll read the book.

The film wasn’t a bad adaptation at all, indeed. However, I think the book is even better, so I’m glad you give it a try! Happy reading!

I first read The Book Thief in 8th grade and it immediately became my favorite book. I reread it again 2 years later. Now I am 23 and finally reread it again and I can still say it is my favorite book. I think my favoeite character is Rudy. I just love him so much. I want to name a future son after him… 🙂

It is one of my favorite books too. I read and reread it countless times. Rudy is an amazing character, a spark of light and joy during the dark times in which the story takes place. All the characters in The Book Thief are amazingly written, and I like them all, but, if I really had to choose one, I think it would be Death. His portrayal was touching yet balanced, and so unexpected! (I wouldn’t name a kid after him, though!)

This book is now a required reading for high school, and this book is amazing and really made me think how bad do we truly have it if they had to live like this? My favorite character was Max, because he tied into the story perfectly and really changed Liesel’s perspective on life.

Despite being written in such a way that even a young teenager can read and enjoy it, I think The Book Thief is multi-layered, it can be appreciated at any age and can trigger many thoughts and discussions. Max, indeed, drives a lot of the plot. Its presence pushed all the characters out of their ‘comfort zone’. Having Max in their basement allows our characters, and Liesel in particular, to grow stronger, better, kinder, smarter. Hans was excellent too, especially when teaching Liesel to read, indeed!

I love this book it is one of my top five favorite books ever! Hans is one of my favorite characters. He is a lights and what would have been otherwise a very dark long night in liesel’s life. It comes to show the strength, bravery, and kindness that the human soul is capable of; it also shows that even though you may think that you’re nothing that no one loves you and you’re worthless that there is someone out there who loves you and who cherishes you even if only for a moment.

The Book Thief is one of my favorite books too! And now I’m curious to know which are the other four books in your top 10!

Hans, is, indeed, an amazing character, he is kind and strong and brave. I don’t think Liesel would have survived any of this without him in her life. By being there for her, and by teaching her how to read, and even by taking Max in, he saved his foster daughter’s life in more than one way (as well as Max’s). As Death sums up, he has a bright soul.

I read this book when I went to Cuba three years ago, and all I did all week was relax and read, really, and it took me the whole week to read it. I finished it on my second last day there. And it was a good thing I had sunglasses on! Because I cried so many times! I loved how touching the story was. A lot of the parts were just… ah. so touching haha. And I think I liked Max the best. But her foster father was also super wonderful. I loved reading about them reading together. ha. that sounds weird.

I just finished it, and I’m speechless, it was amazing, full of emotions, tragedy, love,… I cried so much, my heart at the end, oh God!

The Book Thief is such a well-written and emotional novel, indeed! It is one of the few books that did make me cry too.

I absolutely love this book. It is one of my favorites books of all time. I have it on my Kindle in Spanish, have the English edition that was published when the movie was announced. The movie was wonderful also have this on Blu-ray. Definitely want to buy the anniversary edition.

The Book Thief impacted me like no other book did. Some quotes stuck with me and I remember them from time to time. Liesel- she was so caring.

For me personally, this story is about love and how it manifests over time and connections. How inseparable and unending it is, even after death. And how even though people may not be blood related, they are still family. Honestly, this is one of my favorite books of all time, up there with The Giver.

I’m probably a bit of a lone voice in that I didn’t like the book, and thought the business about turning Death into a character was really contrived.

This book messed me up.

The Book Thief was one of my favorite books, and I loved how the book was not just based off of love, but exploring the different characters, and bringing happiness in the dark times. I just finished reading it for the second time.

The Book Thief is one of my most favourite books of all time, I had the worst book hangover after I finished it.

I read the book with my book group in 2007 and we were all aware then that it was a crossover book – YA but also marketed to adults. In the wake of His Dark Materials, Harry Potter, Curious Incident etc this isn’t so strange: crossover books were all the rage then.

We all hated the book very deeply,

There is a really gripping story here, but the author can’t let it tell itself. Sophie’s Choice, Schindler’s List and The Diary of Anne Frank are masterpieces by comparison.

This is one of my all time favorite books. I think that the way it is written is superior to almost every other book I’ve ever read.

I just finished this book a half hour ago and feel almost awestruck. This was such a beautiful book, despite the tragedy that was WWII. While I, too, loved the majority of the characters by the end, Hans had a slight step above everyone else.

I think that The Book Thief is a metaphysical commentary on not only how we view death or war but also how we view life and how words can breathe life back into us. Also, I truly believe that the movie suffers without deaths commentary, its like having stew without salt. It might sustain you just as well but you miss the salt. Overall I thought this was a very in-depth and erudite commentary on not only a very deep book but also a very hard subject.

I completely agree! Though the era the book tackles is particularly opportune to philosophical and historical commentary, The Book Thief goes beyond that, with metaphysical (or meta-literary, it that’s a word) thoughts on various subjects, going from death to words.

Without the omnipresence of Death, the movie loses something, indeed!

Thank you!

Very illuminating article! I used to read quite a bit of Markus Zusak and while the Book Thief is not my favourite book by him, one can’t but appreciate its depth and literary scope.

Thank you very much!

Which one is your favorite, then? 🙂

I have always found having Death as the narrator very effective, and I think that a lot of that is because he knows what is going to happen and carries the story with an element of weariness because he cannot stop the future.

I agree! Death, as a narrator, is as original as it is effective. To me, Death can – in the Book Thief at least – be compared to the Chorus in Greek tragedies (and in modern ones inspired by this ancient trope). Its presence (or omnipresence) adds, as you said, a sense of weariness. It highlights the relentlessness of the events while providing an insight into the story’s psychological and emotional dimensions, which makes the ending even more tragic.

The Book Thief is one of the best YA books to be published in recent years, and I’m so glad to see an article about it here. Zusak made a risky yet brilliant choice in having Death narrate. As for the theme of books and writing, as a bookworm and writer, that’s probably one of my favorite parts.

I completely agree! The Book Thief is one of my favorite YA books, if not one of my favorite books.

The narrative style might have been a risky bet, but it was brilliantly handled, and, to me, it is what truly drags the story to another level. I think it allows the novel to tackle such a variety of themes, from war and death to books and writing, without weighing too much. The Book Thief strikes me as a wonderful meta-literary work. (…If that is a word. I know it is used in French, and surely in other languages too, but I struggled to find an English translation that sounded right, so I hope that is correct!)

I remember being introduced to Markus Zusak by a friend who I have subsequently lost touch with. While I have yet to read The Book Thief inspite of the sterling things I have heard about it, I must mention I did like The Messenger and Bridge of Clay.

I actually haven’t got the chance to read other novels by Markus Zusak, but that is definitively something I want to do! I heard a lot of good about The Messenger, even though I haven’t read it yet. However, I didn’t know the Bridge of Clay! Thank you! Any (other) suggestions?

Well, I can only urge you to read The Book Thief! Happy reading! I hope you’ll enjoy it! 🙂

I loved this book and this was a wonderful analysis on the three themes!

Thank you very much!

It is an amazing book, indeed!

The Book Thief is my favorite book of all time. I loved the beautiful similes Zuzak crafted and the Death narrator. I teach English to middle schoolers and always recommend this beautiful book to them. Despite this, it is a book for all ages and in some ways can only be fully appreciated by an adult who has experience with life.

I agree! To me, The Book Thief is a multi-layered novel, that can be appreciated at any age!

It’s been a while since I’ve read The Book Thief, though this analysis has left me wanting to reread it! The perspective of the novel is one of the elements that has stuck with me the most since first reading it.

I’m glad to read that! Thank you!

Happy re-reading!

A good essay. I put this movie aside in my mind and thought of watching it, now I will. Good, sometimes what you want from an essay is to awaken an interest, in case watching a movie.

A decent article.

Thank you!