The Good Place: Philosophically Sound?

Imagine that, one day, you wake up in a waiting room, with a wall, right in front, telling you that “Everything is fine”. Then, an Architect calls you into his office and proclaims to you that you are dead. But, thanks to the incredible life you lead, you are in the “Good Place”. That is what happened to Eleanor Shellstrop (Kristen Bell), in the TV show The Good Place. But when Michael the Architect (Ted Danson), shows Eleanor all of her good deeds on Earth, she realizes that these are not her memories. In this heaven-like setting, she is a fraud. She may not have killed anybody, but she was self-centered to a comical degree, often mean, and not at all concerned about the well-being of others. However, as the Bad Place does not seem excessively attractive, Eleanor wants to stay in the Good Place. To do so, she has to learn how to fit in, she has to learn how to be a “good person”. For that, she enrolls her so-called soulmate, Chidi Anagonye (William Jackson Harper), a former professor of ethics. She also has to handle her new neighbors – Tahani Al Jamil (Jameela Jamil) a rich and exuberant British model who raised money for numerous charities, and Jianyu Li (Manny Jacinto), a Buddhist monk who took a vow of silence – while learning that, even in the afterlife, appearances can be deceptive.

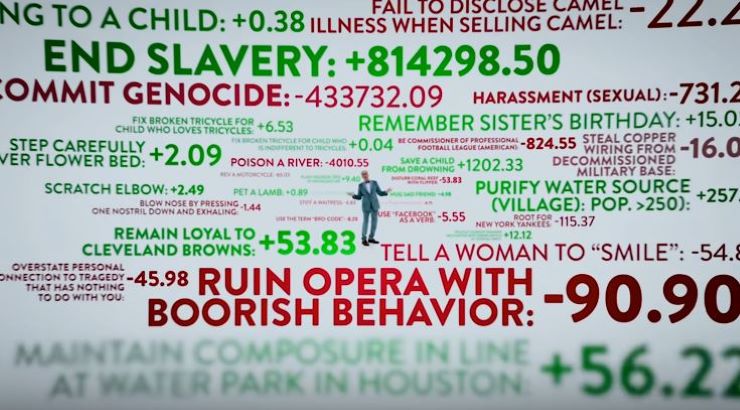

(Screenshot, The Good Place, 1×01)

The Good Place is and stays a comical show. It is fun and light-hearted, we meet some actors who also played in Brooklyn Nine-Nine – made by the same producer, Michael Shur – but The Good Place, while staying a sit-com, tackles some philosophical and ethical issues, especially concerning the debate around morality and what makes a person or an action good (or bad).

How does The Good Place tackle those issues? What are the philosophical undertones of the show? What lessons does it teach us?

A warning, though: there will be some major spoilers, especially in the first part of this article, that tackles the philosophical background of the show. The second part will study the Afterlife’s point system and the philosophical theories it involves, so, once again, spoilers ahead. Finally, some separate philosophical issues that are contained in single episodes will be discussed, in the third part, so, still some spoilers, but this time, minor ones.

The implicit background and philosophical influences of The Good Place’s story-line

“Hell is other people”

Did Michael read Sartre? Well, given how badly he needed some Chidi’s lessons, probably not. But, who knows, he might have crossed path with the French philosopher back in the Bad Place! By some aspects, the first season of The Good Place appears as a modern and comical version of No Exit, by Jean-Paul Sartre. Indeed, in Sartre’s play, we come across three characters – Ines, Estelle and Garcin – in a strange room that turns out to be their own personal hell, just like Michael’s neighborhood was built to be our four characters’ personal hell. In the same way, Michael picked Eleanor, Chidi, Tahani and Jason, Ines, Estelle and Garcin were picked to torture each other for eternity, leading Garcin to say this now-famous quote: “Hell is other people”.

Often misunderstood, this quote doesn’t mean that people can’t co-exist without getting on each other’s nerves turning social interaction into a hellish nightmare. The figure of the “Other” is central in Sartre’s philosophy, as our consciousness doesn’t exist by itself, but by being confronted to others. According to Sartre, the Other reveals a part of ourselves, it allows us to become self-aware. However, the Other’s gaze can also objectify one, alienate one. To illustrate such a mechanism, Sartre, in Being and Nothingness, takes the example of shame: shame exists only because we are subjected to the judgmental look of others. If one is completely alone, there is nothing they could do that would lead them to be ashamed of themselves. Shame only comes along when one knows their shameful act has been seen by the Other. It allows self-awareness. The Other is the mediator between me and myself, almost like a mirror. It is interesting to note that, in No Exit, there are no mirrors in the room, and, as Estelle desperately wants to know what she looks like, Ines offers her to be her mirror, to describe her appearance. In The Good Place, just like in the play, the characters have been specifically chosen because they unwillingly and metaphorically present a distorting mirror to each other, emphasizing their flaws, trapping them in situations that draw the worst of them, situations that are painful for them. And that is where the torture lies.

As Eleanor puts it, in the first season finale:

It looks like paradise, but it’s actually a filthy dumpster full of our worst anxieties. I’m surrounded by people who are literally better than me. Just me being here forced Chidi into an ethical “clusterfork.” Tahani tortured Jason by constantly trying to get him to talk, Jason tortured me because I was sure he would blow our cover, which was torture for Chidi, because he was responsible for me, which made Chidi seem like the perfect soul mate, and that tortured Tahani because he didn’t love her. […] See? We’ve been torturing each other since the moment we arrived, and everything Michael has done has made at least one of us miserable.

(Screenshot, The Good Place, 1×13)

Beyond the conclusion, we can notice several other parallels between the first season of the show and Sartre’s play. In both, hell is assimilated to some sort of bureaucracy, some sort of administrative system, far from the classical view of a burning mystical underground place. It is very clearly showed in The Good Place, with the Judge, the Architects’ bullpen, Michael’s hierarchy, the demons’ union and their claims, and it is used as a comic device. In No Exit, it appears through the character of the “room-valet”, through the hotel-like setting, through words like “staff”, or even through one of Inès saying:

It’s obvious what they’re after: an economy of man-power—or devil-power, if you prefer. The same idea as in the cafeteria, where customers serve themselves.

No Exit, Jean-Paul Sartre

And here, as we already said, dead customers tortures themselves.

Plus, apart from Eleanor, all of our characters, both in No Exit and in The Good Place, try, at first, to convince themselves and the others – especially the others, as it is the only one that matters here according to Sartre’s theory – that they don’t belong in hell, that there has been a mistake somewhere. In the play, Estelle is the more adamant to defend the idea that she doesn’t belong there:

In fact, I’m wondering if there hasn’t been some ghastly mistake. […] There must be thousands and thousands, and probably they’re sorted out by—by understrappers, you know what I mean. Stupid employees who don’t know their job. So they’re bound to make mistakes sometimes. […] [To GARCIN] Why don’t you speak? If they made a mistake in my case, they may have done the same about you. [To INEZ] And you, too. Anyhow, isn’t it better to think we’ve got here by mistake?

No Exit, Jean-Paul Sartre

In the show, Chidi thinks it is because he kept drinking almond milk when he learned it was bad for the environment, Jason is, well, Jason, and Tahani is the more adamant, demanding to speak to the manager, just like she used to do back on Earth. Plus, although that might be far-fetched, we can even notice some similarities between characters in No Exit, and The Good Place: Tahani, like Estelle, have a posh background, and are very stylish (for instance, Estelle choose her sofa so it would go with her dress), Ines describes herself as “cruel” and unable to “get on without making people suffer”, and, to a lesser and more comical degree of course, this type of attitude could match some of Eleanor’s action during her life – lives – on Earth, Garcin, just like Chidi, ends up in a love triangle he never asked for, while his “cowardice” could be the equivalent of Chidi’s “indecision”.

There is one major difference though, between the two: in No Exit, the context is, at first, muddy and mysterious to the reader, but not to the characters. They know they are in hell. It is not the case in The Good Place. On the contrary, our characters – and the viewers – think they are in the Good Place, and, all along the show, they fight to earn their right to go and to stay to the real, actual Good Place. In No Exit, there is no more hope, no more redemption, that’s why the characters can’t agree to stop torturing each other. In The Good Place, there is still hope.

Therefore, Michael’s plan may be inspired by Sartre’s work, but perhaps the Architect should have looked up some other philosophical theories, that could have given him clues on why his experiment was so unpredictable, not to say doomed to fail. In Idea for a Universal History with a Cosmopolitan Purpose, Kant theorized the fact that conflicts between humans are necessary. Though they come from their respective egoism, inherent to human nature, they allow the progress and betterment of societies. It is, for Kant, a way to give a sense to a seemingly chaotic and random History. But, why wouldn’t that be valid at a smaller scale, with, for instance, four people whose antagonism was supposed to be a means of torture, but ended up being a means to grow wiser and better? All of our characters are, at first, egoist, in a way and to a degree. Eleanor’s case is, of course, the more significant, as she displays a classic case of psychological egoism.

Psychological egoism is the strong belief that everybody cares only for their own interest, leading one to behave in an egoistic way to fit the society they imagine where the survival of the fittest is the only rule. Yet, by the end of season one, and, even more, by the end of the show, all of our characters, and Eleanor, in particular, are willing to make sacrifices for each other. Their egoism leads them to oppose and even torture each other, but they arose stronger, better, more united, from those conflicts. Plus, our characters, against all odds, bonded, became friends, and, in some cases, lovers. According to the English philosopher David Hume, moral and moral actions come from “passion”, from feelings, not from reason. Eleanor never really cared for anyone before Chidi, and that is only when she began to have feelings – friendly ones, and then romantic ones – for him that she truly invests herself into being better.

How do you learn to be a good person?

When Chidi takes Eleanor as his student, he says: “It will take hours and hours of studying ethics and moral philosophy. We’re gonna have assignments, and quizzes, and papers! It’s gonna be so much fun!” (1×02 ‘‘Flying’’) But can we really learn how to be good through academic teaching? This question drives the whole show, especially the first season, and it can be linked to meta-ethics, a branch of ethics. Meta-ethics is: “the attempt to understand the metaphysical, epistemological, semantic, and psychological, presuppositions and commitments of moral thought, talk, and practice” 1

Regarding the influences of ethics lessons on actual behaviors, studies have been done, for instance by Eric Schwitzgebel, a professor of Philosophy specialized in empirical psychology, at the University of California, Riverside. They show that ethical lessons do not necessarily lead to moral behaviors Indeed, according to Eric Schwitzgebel, in Order Effects on Moral Judgment in Professional Philosophers and Non‐Philosophers:

Philosophical expertise does not […] enhance the stability of moral judgments against this presumably unwanted source of bias, even given familiar types of cases and principles.

Order Effects on Moral Judgment in Professional Philosophers and Non‐Philosophers, Eric Schwitzgebel

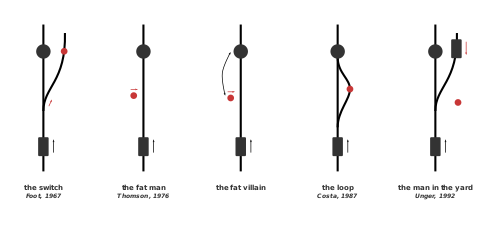

That point of view is illustrated several times in The Good Place. For instance, in the episode ‘‘The Trolley Problem’’ (2×09), we see that Michael struggles to grasp human ethics through Chidi’s lessons and the demon asks for something “more concrete”. In a snap – quite literally – Eleanor, Chidi, and Michael therefore embark on The Ethics Express, for an extremely vivid experience of the trolley’s problem.

On the first attempt, Chidi thinks for too long, and he ends up crushing the five (fake) people, because, by the time he was emotionally ready to pull the lever, it was too late. On the second attempt, Chidi reacts to quickly and does not realize in time that the person alone on the other track is a friend of his, and he ends up crushing him. The show illustrates here that it is one thing to know what you have to do, and it is another to actually do it. The experience quickly becomes emotionally and physically traumatizing for Chidi.

Generally speaking, his character seems to be the living example of that first point. Indeed, as a brilliant academic, he knows basically everything on ethics and morals. But, such an amount of knowledge doesn’t make his life better, on the contrary, as it leads him to be indecisive to a comical degree. And such behavior does not only tortures him but everyone around him, which is why he ended up in the Bad Place, among Michael’s guinea pigs. He even acknowledges the limits of philosophy, when, as Michael is going through an existential crisis, in the episode “Existential Crisis” (2×04), he says: “I mean, emotionally, he’s [Michael] all over the map right now, and I can’t believe I’m saying this, but I don’t think this can be solved with a book”.

(Screenshot, The Good Place, 2×09)

However, concurrently to her lessons, Eleanor does seem to get better at being better, regularly using Chidi’s words during some of their debates to justify and explain why and how she acted. The situations our characters are put in match Chidi’s lessons, and therefore allow the protagonist to draw some parallels with Chidi’s teaching, or, at least, to think about it outside of the classroom, in the real (after)life.

Knowing ethics and philosophy does not necessarily lead to be a ‘‘good’’ person. However, it opens the door to self-reflection, it gives some tools that individuals are free to use or not in or lives – or afterlives here. Or, to speak like moral intuisionism, a branch of meta-ethics, the members of team Cockroach lack, at first, of “Moral Intuition”, and Chidi’s lessons allow them to build such an Intuition, they help us adjust their moral compass.

Contractualism as the “spine” of the show

A book that keeps coming back throughout the entire show is the book What we owe to each other, by T.M. Scanlon, an American philosopher at Harvard University. According to Michael Shur, Scanlon’s book is the “spine” of the show. We regularly see it on Chidi’s desk, and it is the title of the sixth episode of the first season, where Chidi summarizes Scanlon’s contractualism:

Chidi: Imagine a group of reasonable people are coming up with the rules for a new society.

Eleanor: Like: “If your Uber driver talks to you, the ride should be free”?

Chidi: Sure, but anyone can veto any rule that they think is unfair. So, if you said, “We should be able to break our promises without any repercussion”, someone would veto that rule”.

It is also on Scanlon’s book that Eleanor wrote a note to herself in the first season finale. It is through a conference gave by Chidi on What we owe to each other, that Eleanor reconnects with him in the third season, and, finally, it is the book she finishes reading in the last episode of the show, and it helps her deal with Chidi’s resolve to go through the door. As she says herself:

The whole book is about how we should try to find rules other people can’t reasonably reject, and then he ends it by saying, “The search for how to find those rules will go on forever. ” I proposed a rule that Chidi shouldn’t be allowed to leave because it would make Eleanor sad, and I could do this forever, zip you around the universe showing you cool stuff, and I’d still never find the justification for getting you to stay. Because it’s a selfish rule. I owe it to you to let you go.

Scanlon’s contractualism belongs to the field of moral philosophy and ethics, as it revolved around the notions of good, bad and morality. As Scanlon wrote himself, in What we owe to each other:

[a]n act is wrong if its performance under the circumstances would be disallowed by any set of principles for the general regulation of behavior that no one could reasonably reject as a basis for informed, unforced, general agreement.

What we owe to each other, T.M. Scanlon

Such a theory is, implicitly, at the heart of many discussions with the Judge. Indeed, Michael, thanks to its experiment, proved that humans can get better after they die, therefore, he can reasonably object that the ancestral system is wrong. Contractualism is also at the heart of the creation of the new system, where all reasonable parts – the Judge, Shawn, Michael, and the Good Place committee – must agree. But Scanlon’s thought, as expressed in the show, and as we can see in both Chidi’s and Eleanor’s explanations, go beyond legal aspects. It encompasses the human dimension. As T.M. Scanlon said himself in an interview published in the The Crimson:

The central chapters, chapters four and five, set out and defend a way of thinking about a certain aspect of morality I want to call “what we owe to each other.” This doesn’t cover all of what we normally call “morality,” but it captures a central section of it: Our obligations to other people in general.

And that is what our characters – and Eleanor in particular, as her main flaw is selfishness – discover, throughout the show. Our four characters, six if we include Michael and Janet, are all, to a degree and in different ways, selfish. But, by being forced to live and work together – to save their souls from eternal damnation, and then to save all of humanity from eternal damnation – they learn to coexist peacefully, to make compromises, and to accept one’s veto. They form bonds, and, together, they build a fairer and better moral system. They are led to discover, to respect, and to honor what they owe to each other – and that is, according to Michael Shur is at the core of the show:

We owe [things] to each other. You owe certain things to the people that you share Earth with and that’s the point of the show, very explicitly.

Source

The Good Place is, then, inspired by many philosophical tales, theories, and issues, but it also builds a system of its own. It reshapes a vision of the Afterlife, based on a point system, that confronts different philosophical views on good and bad.

The point system in The Good Place’s Afterlife

In an hilarious scene, in the episode “Jeremy Bearimy” (3×04), where Chidi goes nuts, he explains the three major ethic theories to judge the morality of actions and people: consequentialism, deontology, and virtue ethics. We can find parts of those theories, as well as debates regarding their respective limits and blind spots, in the functioning of the Afterlife.

(Screenshot, The Good Place, 3×04)

Consequentialism

To determine whether someone belongs in the Good Place or the Bad Place, the Afterlife uses a system of points, that Michael presents it in the first episode:

Welcome to your first day in the afterlife. You were all, simply put, good people. But how do we know that you were good? How are we sure? During your time on Earth, every one of your actions had a positive or a negative value, depending on how much good or bad that action put into the universe. Every sandwich you ate, every time you bought a magazine, every single thing you did had an effect that rippled out over time and ultimately created some amount of good or bad. You know how some people pull into the breakdown lane when there’s traffic? And they think to themselves, “Ah, who cares? No one’s watching.” We were watching. Surprise! Anyway, when your time on Earth has ended, we calculate the total value of your life using our perfectly accurate measuring system. Only the people with the very highest scores, the true cream of the crop, get to come here, to the Good Place. What happens to everyone else, you ask? Don’t worry about it. The point is, you are here because you lived one of the very best lives that could be lived.

As he speaks, we see examples of actions and the points they add or remove.

(Screenshot, The Good Place, 1×01)

Most of the items may sound silly, but not all of them. For instance, “Fix[ing] broken tricycle for a child who loves tricycles” adds 3,36 points, while “Fix[ing] broken tricycle for child who is indifferent to tricycles” adds only 0,04 point. As presented by Michael, the system seems to be consequentialist.

According to consequentialism, we can assess the goodness of an action by its consequences. The happiness, the good that emanates from the action of fixing a tricycle won’t be the same depending on how much that kid enjoys tricycle. In the same way, “End[ing] slavery” adds a lot of points because of its good repercussion on a large and long scale. A good action has to bring some actual good in this world, sole intentions can’t be enough. As the old proverb says “Hell is paved with good intentions”.

However, this theory has some limits, and the show points them out. In the third season, in the episode “Don’t Let the Good Life Pass You By” (3×08) we learn that in fact, nobody got to the Good Place in over 500 years. Indeed, our world has become more and more complex, and an action that, in itself is good and earns points may be linked or may trigger bad actions, that remove even more points. That is what Michael discovers in the episode “Book of Dougs” (3×10):

In 1534, Douglass Wynegar of Hawkhurst, England, gave his grandmother roses for her birthday. He picked them himself, walked them over to her, she was happy… boom, points. […] In 2009 , Doug Ewing of Scaggsville, Maryland, also gave his grandmother a dozen roses, but he lost four points. Why? Because he ordered roses using a cell phone that was made in a sweatshop. The flowers were grown with toxic pesticides, picked by exploited migrant workers, delivered from thousands of miles away, which created a massive carbon footprint, and his money went to a billionaire racist CEO who sends his female employees pictures of his genitals. […] [E]very day the world gets a little more complicated, and being a good person gets a little harder.

Or, as Tahani puts it: “there are too many unintended consequences to acting”. Humans can’t consider and ponder every implication their actions entail. If they try, they end up being so indecisive that it becomes unlivable, and, just like Chidi, they end up in the Bad Place anyway. Plus, we can add that some good deeds, such as ending slavery for instance, require more than just goodness. For some actions, the situation has to be suitable, you probably need some qualities that are not directly related to being good, and surely a bit of luck isn’t too much to ask. Can we honestly judge the good in someone by considering the opportunities or the luck they got in their life?

Deontology

In the same way, can we honestly take the intention behind the action out of the equation? No. At least, not in The Good Place.

Tahani raised millions of dollars for charities. According to sole consequentialism, she should go to the Good Place. But she did so only to prove her parents she was better – or at least equal – to her sister. She did not truly care for the people she helped, she was only motivated by her jealousy towards Kamilah. Her intentions weren’t “pure”, therefore her actions weren’t truly “good”, and that’s why she ended up in the Bad Place. Similarly, in “What’s my motivation?” (1×11), when Eleanor tries to improve her score, it doesn’t raise enough because she is doing it in order to avoid going to the Bad Place, her motivations are still interested and self-centered. As the Judge states in the episode “Somewhere Else” (3×12): “You’re supposed to do good things because you’re good, not because you’re seeking moral dessert”. This point of view, centered on the purity of the intention, was strongly defended by Emanuel Kant – Chidi’s role model – and, more generally by an ethical school of thought: deontology.

According to deontology, some principles are universal, which means that they apply to anyone unconditionally. You can break them if you want, but by doing so, you can’t logically think that anyone other than you should break them too – you can’t wish they wouldn’t apply universally. To deontology, and to Kant in particular, “radical evil” is the subordination of the moral law to selfishness, to self-conceit, to egoism, to what Kant calls “self-love”, where it should be the contrary. Plus, it is the intention behind the action that matters: in Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals Kant wrote that a “good will” would “still shine like a jewel” even if it were “completely powerless to carry out its aims”.

But, once again, while addressing the relevance of such a theory – in Tahani’s case, and with the idea that behaving in a way seemingly “good” way just to have “moral dessert” is not truly ‘‘good’’ – the show also points out the limit of such reasoning. For instance, one of Kant’s and deontology basic principle is that you should never lie. Many thought experiments pointed out the limits and weakness of such a rigid stance, and The Good Place staged one too, in “Rhonda, Diana, Jake, and Trent” (2×10). In this episode, the team goes to the Bad Place undercover, and Chidi is terribly conflicted – even more than usual – because he will have to lie, and that goes against everything he believes in. But, in this situation, not lying would not only put him in an extremely bad and hazardous situation, but it would also put the whole team, his friends, in an extremely bad and hazardous situation, which wouldn’t be fair to them. And Eleanor tries to convince Chidi, by using Johnathan Dancy’s moral particularism:

Moral particularism says there are no fixed rules that work in every situation. Like, let’s say you promised your friend you’d go to the movies. But then your mom suddenly gets rushed to the ER. Your boy Kant would say never break a promise. Go see “Chronicles of Riddick.” Doesn’t matter if your mom gets lonely and steals a bucket of Vicodin from the nurse’s closet. […] You have to choose your actions based on the particular situation and right now, we are in a pretty bonkers situation.

Such a “bonkers” situation, to keep the show relatively light and funny, is not presented as being as implacable as Comte-Sponville’s thought experiment staging Gestapo soldiers knocking on your front door and Resistance fighter hiding in your attic, as the high stakes for our heroes are sugarcoated by humor and comical deflection, but it still points out some of deontology’s flaws.

Virtue ethics

The first theory that Chidi teaches Eleanor is Aristotle’s virtue ethics. Such a theory stands out from consequentialism and deontology as it is not centered on what makes an action good, but what makes a person good. According to Aristotle, virtues are moral qualities that one can acquire or lose. Goodness or badness is not innate. You are not born good, you become good. It is an ongoing process, that we can compare to Plato’s image of the fractured line. To become good, you have to do good actions, you have to exercise and copy these moral qualities. At first, you may have to force yourself to do so. It is hard, it doesn’t come naturally, but, according to Aristotle, the more you do it, the more it becomes natural, until it becomes your nature, until you become ‘‘good’’. It is what Eleanor tries to do throughout the first season, starting with her decision – thanks to Chidi’s strong incentive – to go pick up garbage to help the community instead of going flying for her own enjoyment – even if she ends up cheating pretty soon (“Flying”, 1×02). It is also with this theory in mind that Eleanor tries to make a good person – or at least a less “shirty” person – out of Brent, in season 4. When Michael is surprised by Eleanor’s lies to Brent, as she just said to him that there is indeed a “Best Place” he could gain access to if he behaves nicely, she defends her decision, by saying: “We have to hope that, over time, Brent starts doing good thing out of habit”, to what Michael responds: “Just like you” (4×02).

Aristotle’s theory is absent in the first Afterlife point system, as counting stops the moment you die, but it is at the heart of the show, and at the heart of the new Afterlife system. Indeed, in the last season, the system to count points during life on Earth remains more or less unchanged, a muddy mix between consequentialism and deontology. What truly changes, is what happens after you die. Instead of being sent either to the Good or Bad Place immediately, people are sent to a new kind of Medium Place that, similarly to Michael’s first experiment, allows people to be confronted to their fears, theirs flaws, their dilemmas, their shortcomings, while not being trapped in the endless stings of consequences that exist on Earth, so they can become better and better until they are good enough to go to the actual Good Place and be reunited with their loved one.

At the center of the new Afterlife System is the Aristotelian idea that being good is a learning process, that, with time, everybody could achieve. That is what our characters did, throughout the show. By the end of the last season, they have fixed their major flaws. In the last episode, Chidi easily makes choices, whether it is to choose the dessert or his decision to go through the “final door at the edge of existence”, Jason, by waiting for Janet to give her the necklace, proves his patience and monk-like abilities that go against his initial impulsiveness, Tahani made peace with her family and spent meaningful moments with them before deciding to become an Architect to do actual good, Eleanor build a true bond with the team, she overcomes her selfishness, she manages to let go of Chidi, even if it is not without struggles, and her last act is to selflessly allow Michael to achieve his dream of understanding humanity, by becoming an actual human.

Goodness, and how to judge it is, by many aspects, at the center of the show. But, at times, circumstances lead Chidi to extend his lessons to other philosophical topics.

Two side-lessons by Chidi Anagonye, and one by Michael

Identity

As it was already said, in The Good Place, our characters die twice, their mind is regularly rebooted, their memory deleted, and then stuffed again with the memories of several lives. And that leads them, and Chidi in particular, to question their identity. It is particularly flagrant in the episode “Janet(s)” (3×09). At that point, Michael already gave Eleanor’s memories back, but he didn’t do it for the rest of the team, and especially not for Chidi. Therefore, when Eleanor fall in love with Chidi once again, she remembers them being a couple in previous afterlives, but Chidi doesn’t remember any of this and he struggles with Eleanor’s love declaration. That leads them to a lesson about identity, while they are in Janet’s void.

At first, one might say that identity is defined by corporal continuity. I am ‘‘me’’ because I possess a body that, as a functional organism, is continuous, and stay the same, as a functional organism – we know that all our cells are regenerated every seven years or so – all along my life. However, such a stance was quickly dismissed by modern philosophers, as it was in the episode. Indeed, our characters are in Janet’s void, they all look like Janets, and their physical bodies have been disintegrated. Yet, they are still them, right? But, which them? The first part of Chidi’s lesson tackle John Locke’s theory of identity. According to the English philosopher, it is not the continuity of the body, but the continuity of the conscience that matters, and such a continuity can be approached through memory. Therefore, in our case, the Janet-Chidi is not the same being that Eleanor’s lover-Chidi, because he doesn’t remember being Eleanor’s lover, nor does he remember having feelings for her. To quote (Janet-)Chidi: ‘‘If I can’t remember what happened because it happened to a Chidi from another timeline, it’s not a unified me.’’

Of course, such a stance is not flawless, and his students are quick to argue:

Eleanor: Just because you don’t remember doing something doesn’t mean you didn’t do it!

Jason: I have no idea how it happened, but there is definitely a tattoo on my butt that says ‘Jasom’.

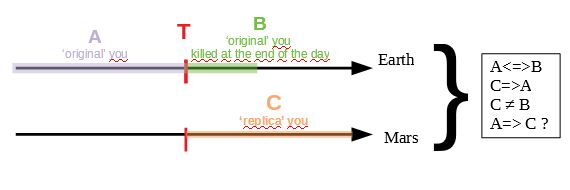

So, Chidi’s uses Derek Parfit’s theory, then Hume’s, to conclude that “in essence […] we don’t truly have a self. We’re just a bundle of our ever-changing impressions.” The show, as presenting an academic philosophy class is not its primary goal, cuts some of Chidi’s explanation. Let’s fill some holes. In his book Divided Minds and the Nature of Persons, Parfit uses and deepens the so-called ‘‘teletransporter paradox’’.

Here is how it goes: let’s say you are on Earth, and you enter a teletransporter in order to go to Mars. The device analyses your entire being, memories included, and this process destroys your body. Then the teletransporter sends the data to a similar device on Mars, that recreates you. When you wake up on the red planet, your body is brand new, made with local atoms of carbons and oxygen, but you are you, because your memory is intact. You remember everything that happened to you on Earth. That is Locke’s theory. But now, let’s say that the teletransporter is upgraded: it doesn’t have to destroy your body in order to send your data to Mars anymore. Therefore, each time you take it, a replica of you created, on another planet. But that replica possesses all the memories of the ‘original’ you. According to the conclusion of the first experiment, the ‘replica’ is as much ‘you’ as the ‘original’ you. There are now two yous wandering off in the universe! Such a state of affairs may entail numerous issues, especially concerning legal and moral responsibility. Yet, it is closer to what our characters in The Good Place are experiencing: two versions of themselves. However, in the show, and contrary to our teletransporter example, the different versions do not coexist. As Chidi puts it: ‘‘All I know is that other Chidi doesn’t exist anymore, and this one does. So this must be the real Chidi.’’ Now, let’s say that, considering the ethical issues the teletransporter poses, the government decides that having several versions of the same individual existing at the same time is illegal. However, engineers can’t restore the previous version of the teletransporter. It is then decided that the teletransporter will continue to send your data to Mars where a ‘replica’ will be made, while, back on Earth, at the end of the day, all the ‘original’ individuals will be killed. Knowing that, do you enter the teletransporter?

We can sum up the situation with a scheme like the one above. Here, A identifies to B and B identifies to A because there is a physical and psychological continuity between person A and person B. C identifies to A because there is a psychological continuity, the memories of person A are the same as person C (Lockian principle). But, person B, as they exist at the same time as C, and know that they will be destroy shortly, can’t identify to C, and vice versa. Therefore, does A identifies to C? Once again, do you enter the teletransporter? Parfit proves, then, that the criteria to define identity is not unique. It depends on your point of view (A,B or C) and considers temporal data. There lies the problem, and, as a consequence, the existence of the self itself that is in danger.

Hume – who inspired Parfit’s works – also reached this conclusion, though with less sci-fi. Indeed, to Hume, memory can’t give us the continuity we are looking for, as we are prone to forget or misremember some events. With time our earlier memories become less and less clear, more and more blurry. And, as time can be split to infinity, we can’t set a reasonable threshold that would preserve the argument. Therefore, according to Hume, there is only a succession of distinct instants, a flux of distinct micro-experiences that only gives the illusion of unity, where there really no unity at all. Hence Chidi’s masterful conclusion: ‘‘We’re just a bundle of our ever-changing impressions’’ and the disappearance of the “self”.

Yet, to Hume, such an illusion, such a ‘‘fiction’’ is useful – if not necessary – to survival, to societies, to our world. Therefore, when Eleanor starts to freak out and her sense of self begins to dissolve, threatening Janet’s void, and her friends’ very existence, Chidi have to remind her who she is, through memories:

You’re Eleanor Shellstrop from Phoenix, Arizona. Your favorite meal is shrimp scampi. You listed your emergency contact as Britney Spears as a long-shot way of meeting her, and your favorite movie is that clip of John Travolta saying “Adele Dazeem.” You flew halfway around the world because you wanted to be a better person, and it was very brave. You’re sharp, and you’re strong […] and your worst nightmare is someone saying something nice about you to your face, but too bad because I need to say it because you deserve it.

The “fiction” of the self, is necessary.

Reality

(The Good Place, 4×01)

The Good Place’s Afterlife System is pretty crazy, with over-the-top characters and unbelievable situations. It might even lead someone to question the reality of it all. The question of reality wasn’t the main topic of an episode and we didn’t even get to see Chidi explaining it on a blackboard. However, as that issue concerning reality almost doomed all of human afterlives, it might deserve to be considered. At the beginning of the fourth season, Chidi’s ex-girlfriend, Simone, dies and is picked up by Shawn to be part of the team’s new experiment. However, the former neurologist doesn’t believe in this version of the afterlife and thinks that all of it is a figment of her imagination caused by her dying brain. Therefore, she behaves with no restrain, pushing people in the pool, knocking over cake tray, and cutting people ponytails, because why not? To her, none of this is real! Simone’s behavior is, indeed, childish and comical. However, to an extreme degree, it embodies Renée Descartes’ philosophy. This 17th-century philosopher took, among others, the example of a stick put in a body of water: the stick is straight, but, when it is in the water, we see it bend, twisted. Therefore, according to Descartes, and despite what the empiricists claimed, in the field of knowledge, perceptions are not reliable, and what he called ‘‘deduction’’ is the only true method. Such a stance was not only revolutionary in philosophy, but also – and maybe even more – in science.

Descartes himself was as much a philosopher as he was a mathematician and a scientist. And, in The Good Place, Simone was a scientist, back on Earth. Descartes goes even further with his thought experiment featuring an “evil genius”, a thought experiment Simone took a bit to literally. If senses aren’t reliable, and given the fact that we have access our environment through our senses, the world itself could be an illusion, a lie, a dream. What if a demon of ‘‘utmost power and cunning, has employed all his energies in order to deceive me’’ (Meditations On First Philosophy)? In that case, the only thing one can take for granted is their own consciousness – ‘‘cogito ergo sum’’ (‘‘I think, therefore I am’’) – while the rest of the external world loses all meaning. And that is what Simone does, questioning and doubting everything around her. However, in Descartes’ philosophy, the ‘‘radical doubt’’ or “Cartesian doubt’’, that stems from this thought experiment is only a step in the process of gaining knowledge, as it allows one to free themselves from preconceived opinions and idea, but it is not the final stage of reflection. Simone is stuck in this solipsistic state of mind, and she needs Chidi’s help.

The alternative the professor exposes to her might be inspired by Pascal’s wager. Originally, Pascal’s wager is about the existence of God. Here, Chidi’s wages the existence of the Neighborhood and the reality of the people in it. If indeed, it doesn’t exist, well, Simone would have been right, and she would have gained a finite amount of pleasure by cutting off people’s ponytails and pushing them in the pool, before she actually dies. However, if it does exist, Simone would have spend a lot of time being a ‘‘jerk’’ to the residents, and they won’t forget it, they will even make her pay, so Simone loses. In Pascal’s wager, the loss is eternal damnation. Here, it is not what Chidi’s have in mind – even if ultimately, Simone’s crazy behavior may truly doom all of humanity – but let’s take the hypothesis that, here, the losses are bigger than the gain too. Now, if Simone decides to believe in the Neighborhood and, therefore, behaves accordingly, but it turns out to be fake, she wouldn’t have gained as much as in the first scenario, but she wouldn’t loose much either. So, rationally, believing that the Neighborhood is real is the best option, as it is the one with the greater gain and the smaller loss. Of course, Chidi doesn’t detail all of this – that is why that last part might be a bit overanalyzed – he only says:

You know, in a larger sense, if you go around acting like no one else matters then you end up […] acting like a jerk. Why not treat them better just in case they’re real? I mean, what do you have to lose by treating people with kindness and respect?

That last bit may also be a reference to Kant’s human formula that stipulate that humans are not to be used as mere tools, but as an end in itself, which, among others, entails treating them with respect.

Sisyphus’s rock

In the episode “Mondays, Am I Right?” (4×11), Michael refers to the Myth of Sisyphus – and especially to Albert Camus’ philosophical rewriting of the Myth – to explain why he is in such a bad mood:

I had to roll a rock up a hill over and over and it kept rolling down […] pushing the rock up the hill gave me purpose. […] Who am I if the rock is gone?

According to Camus, the useless and endless and stupid task of rolling up a rock is what gives Sisyphus purpose. In Camus’ philosophy, human life is essentially meaningless, there is no cosmic plan or divine scheme. It is up to us, as individuals, to make our own meaning, to find purpose in our activities, no matter how repetitive and useless they seem. That is what Sisyphus does. Rolling his rock doesn’t make him miserable, on the contrary, it even makes him happy.

This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

The Myth Of Sisyphus, Albert Camus

But, if his rock was suddenly taken away from him, then, he would be miserable. Such an analysis can be made, not only about Michael’s character, and the numerous trial and setbacks he had to go through, but also on a larger scale. [Warning: Spoilers ahead until the end of the paragraph] Indeed, over the course of the show, our beloved characters are prone to lose their memory: they are rebooted more than 800 times, then they are sent back to Earth to convince the Judge that human can become better on their own without knowing anything about the Bad and Good Places and what happens there, then Chidi’s memory is erased so he could deal with Simone, etc. All the progress made by our four humans are constantly deleted, while their attempts to get to the Good Place are, each time, countered, just like each time Sisyphus approach the top of the hill, his rock roll back to the bottom. Yet, as frustrating as it may be for the audience, it is also what drives the show, what gives it purpose.

In a way, this is also what happened to the people in the actual Good Place. They rolled their rock to the top of the hill, and, they celebrated their victory in this heaven-like place. And, yes, at first, they are happy and satisfied, but, once again, at some point, they miss their rock, their purpose, and, to some degree, the difficulties, the hardships and the efforts that go with rolling the rock. They also miss the constant mystery and unknown of real life. That’s why, despite being in the Good Place, they are miserable and zombie-like.

Michael doesn’t often quote philosophers, but one might assumes that the Architect has a special bond with the French philosopher. Indeed, in the episode “Existential Crisis” (2×04) Chidi explains the phenomenon, saying to Michael that: “an existential crisis is an acknowledgment that life is absurd”. It might be a reference to Camus as well, as the absurd was one of his favorite subjects. His Myth of Sisyphus even is part of a segment of Camus’ work called the Cycle of the Absurd, along with The Stranger, Caligula, and The Misunderstanding.

Works Cited

- Sayre-McCord, Geoff, “Metaethics”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2014/entries/metaethics/>. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

This show definitely helped me because I am almost identical to Chidi in decision-not-making and seeing myself in this particular mirror made me work harder on myself. As Samuel Beckett said: “All of old. Nothing else ever. Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better”.

The problem with most ethics and morals is that they are ultimately relative without a ultimate being who creates things and people for a purpose ( like God) otherwise there is no true backbone for the ethics. They would basically be syllables muttered by some minuscule accident in a sea of obscurity.

*Applause.* The ethics and morals have to have a purpose and they have to come from somewhere. The problem is that because not everybody believes this (and they don’t have to), you get into a situation where you find you cannot “legislate” morality (my entire GRE writing section prompt was about this).

This show is great… except for Jason I cannot stand him. I get it, it’s still using the ‘sitcom’ formula and he’s a the stereotypical ‘dumb’ character… but he’s too dumb. He adds so little to discussions and often just seems like an obstacle that gets in the way of the flow of the conversation. I’m not saying you can’t have a dumb character but I feel like it didn’t need to be this exaggerated. Thankfully in the second last episode, he wasn’t as bad.

Isnt the entire show just a drawn out exercise of Rawls’ wide reflective equilibrium?

I’m not an expert on Rawls, so I did some additional researches. Indeed, our characters adjusted their beliefs (both general principles and particular principles) to reach, by the end of the show, a state of “equilibrium”. It is particularly true with Chidi, isn’t it? In the first episodes of the show, Eleanor traps him by confronting two of his general principle (not lying and not breaking promises) to her particular situation, after he promises to help her, which will entail endangering himself and lying. However, for the other characters, the conflicts mostly seem external. You piqued my curiosity, though! Could you enlighten me more, or even correct me, if I’m wrong?

Anyway, thank you very much for your interesting and stimulating comment!

Actual weird philosophy question: if moral intuitionism is right, then is there ANY actual value to learning ANY ethical philosophy theories?

I would think the value in exploring ethical philosophy is to understand helps us understand why moral intuitionism is right. That is, how could we know that a system works without having comparison?

I’m depressed and when I saw the first few episodes off season 1… no show has ever made me go down a really dark depression spiral, ever, and I’ve seen Serial Experiments Lain, Neon Genesis Evangelion, Bojack Horseman… like, really sad and cynical stuff… but no, The Good Place of all things did me in. A comedy about ethics. Literally made me cry myself to sleep wishing I didn’t exist. It was probably a trigger for something else too, but damn.

Now I’m on season 2 and doing much better, especially while knowing season 1 was based on a lie.

Greetings Dirk,

I hope you are doing better! It sounds like you were/are going through some depressive episodes, especially if this show took you into that dark of a place.

I have been there as well. What you were/are going through is a bio-chemical issue, that is not normal, and can absolutely be treated, and get you out of the darkness.

Please find a good psychiatrist, that can provide both counseling, as well as prescribe anti-depressants. She/He will definitely also recommend an intensive exercise program, as well as other methods for addressing the depression.

Combined with anti-depressants that directly affect your biochemical imbalance and you WILL GET BETTER.

Feel free to contact me if you want. I can help you find the right resources, if you need me too.

Dirk, here’s to you getting better soon,

-Craig

I like how 1st season Chidi was represented as a French guy and he speaks French but his words were automatically translated to Eleanor because they were in the good place and later on when they were sent back to earth he was sent to America and spoke English????

I think there’s a philosophical aspect to this that wasn’t mentioned. Ethics professors themselves might not be all that ethical but they are compared to their 5th century B.C.E. counterparts or their 18th century C.E. counterparts. Society grows morally as it’s studied. Although the reason for that is most likely modernity and technology that makes our lives easier but we should study it all the same.

Really interesting read! I’ve seen this on Netflix but have been hesitant to start watching. This definitely makes me want to start the series!

Thank you very much! I can only advise you to give it a try! (And I hope my article – as it contains a few spoilers – won’t diminish the enjoyment of watching the show!)

A well written essay about a good show. After seeing the series, in fact just watching it straight through over a week, this essay enhanced the enjoyment of the show.

Thank you very much!

I’m glad it did! I always enjoy reading or watching analyses or essays on shows, movies, or books I enjoy, but being on the writing end is really satisfying too!

And also, thank you for your review during the editing process!

I respect the depth and thoroughness of this article very much. I’m actually not a fan of The Good Place; as a devout Christian, I tend to think it’s disrespectful not only of my interpretation of the afterlife but other religions’ interpretations. That said, I can see how Netflix’s version would be comforting and entertaining to some. And I admit, I identify with Chidi on many levels. I, too, would probably crush people out of emotional hesitation to pull the lever. 🙂

Thank you!

That is a very respectable and positive view of things! I would quote Voltaire: “I may disagree with what you have to say, but I shall defend to the death your right to say it”, but there is no proof he actually wrote that sentence – though he might have said it.

I am not a churchgoer myself, but I understand (and respect!) your point of view. Just out of curiosity, did you watch the all show – despite not agreeing with some aspects of it?

I have a lot of common points with Chidi too!

Anyway, thank you for your kind comment and your review during the editing process!

I’ve watched some of it, but not much. There’s not a religious rule against it, per se, but it’s kind of like, we’re careful what we expose ourselves to, and The Good Place could be seen as embracing false doctrine in a lot of evangelical circles. With that said, we don’t live in bubbles, either. I wasn’t hooked on what I saw, and if I don’t 100% love it, I probably won’t finish the series, no matter what it is. But Eleanor and some of the others seemed endearing.

Interestingly, it seems like The Good Place, despite being set in an afterlife world, isn’t really about death at all, but about life. The real question it’s asking seems to be what the “good life” is, how you would recognize it, and whether it’s even possible.

I totally agree! The Good Place truly is about life, not about death! To me, it is about how to live a good life and how difficult it can be, about how to better ourselves if that’s even possible, and also about what truly matters in said life. On that aspect, the fact our characters are dead is, I think, only a gimmick to put things – and here, life – into perspective, as it is always easier to think on and to analyze something when said thing is over, complete, allowing distance and overview.

When I heard the plot of the good place from a friend and said Oh so it’s like a modern No Exit? And they had no idea what I was talking about. It made me very sad.

I’ve had that happen to me before, a lot. Not a lot of people get my references or jokes. It’s okay, though. It makes finding people who “get” me even more special.

I feel like especially in season 2 there’s a conversation to be had about whether or not it’s fair to judge a person’s actions without taking their environment into context. Eleanor learns to be good in the Good/Bad place because all of her external problems have been taken care of (food, shelter, etc) and she has the time to focus on learning to be a better person. The last episode of season 2 shows us that in real life she struggles and falters a few times because the trials and pressures of life make her journey of self-improvement incredibly difficult. I also think the fact that Michael’s character goes from being a demon to a crusader against the system is another add-on to this argument. A demon who simply lives to torture people might never question his/her role, but a demon who learns to know those people as human and gets to know them personally might suddenly have a change of heart. The fact that he calls out the system as unfair is (I think) the show’s big philosophical reveal this season and might be the best commentary it has made on religion and ethics so far.

I agree! The show, and especially in the second and third seasons, challenges some simplistic and purely theoretical or ethereal views on good and bad. The Judge illustrates it well. As an eternal and superior being, she doesn’t know the challenges and hardships humans – or, at least some humans – face during their time on Earth. She doesn’t know how such challenges and hardships can affect their possibilities and opportunities to be good or bad. After quickly going herself on Earth at the end of season three she even admits so (though, by the end of the fourth season, she is ready to erase the Earth…). To use a biblical analogy that I hope is suitable, I think the Judge and The Good Place’s afterlife system still judge humans as if they still lived in the Garden of Eden, even though they don’t anymore.

That makes me think of C.S. Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters (one of those that is always on my TBR pile, but the pile is so big I never get to it). Of course, the demon in Screwtape has no sympathy for humans–or at least is not supposed to–because he works for Satan and in Christianity, Satan despises humans. But he’s also a demon-in-training, which adds wrinkles.

The way I saw it, they got better and improved because they were so different. They each had flaws, and strengths that helped eachother grow. Chidi had the smarts, but was too indecisive to put them to use, while Eleanor was direct and quick at making decisions and could go with the flow. Tahani was obsessed with self image, while Jason didn’t care what anyone thinks.

There are many examples like these of how the group fits together and improves eachother based on the strengths and flaws of each of them.

Sure there was no single good person for then to learn from as an example, but combined they all make for one great person! They didn’t need a single good person to learn from.

I think, had they all been similar and had similar flaws, it never would have worked and they wouldn’t have improved.

The show makes it clear that hell is not other people, sure, they torture eachother first, but they ultimately helped eachother, learned and became better people.

I don’t think her time in The Good Place affected her time on Earth. She began to idolise the man who saved her, and having such a close shave with death made her consider whether she she’d become the best person she could be.

Ok one thing that really erked me wirh the show is thst how it completely ignores sociology and social justice when it comes to efforts of making yourself a better person. They just do generic good things, they don’t bring the conversation into actually challenging or getting rid of systemic oppression. They kinda talk about this during the last season. (I’ll leave it at that so I won’t spoil) but they never go, “hay, lets get rid of homophobia forever” as an actual goal to not just make themselves better but also the world. It’s so glaring when the whole show is about morality and is missing one of the main pillars that is about morality.

I see what you mean, and in a way, I agree. But I think it wasn’t the main subject of the show, or, at least, the angle the show choose to tackle good and bad. To me, the show approach morality and ethics on a micro-level, focusing on the individuals themselves. What you are talking about takes place, I think, on a more macro-level, focusing on societies or groups, and, therefore, calling for a (completely?) different analysis. Changing the level, the focus, could have been very interesting, but it could also have lead the narrative to wander and the show to lose its consistency. Perhaps the writers, directors, and producers wanted to avoid such a drift?

Jason is dumbass who pretends to be a buddhist monk, who ends up marrying the vessel of all knowledge in the universe because he is not “really” attached to anything.

I don’t know if it is just me but The Good Place actually helped me become better and more positive as a person and i learnt a lot about life through a sitcom, more than i’ve done through mandatory school’s moral science classes.

Well, I can only be glad it did! I think that this is how you recognize great shows. Great shows are not only the ones you enjoy while watching them but also the ones that help you grow as an individual, the ones you learn from, the ones that stick with you long after you have finished them!

I gotta say so far those 3 seasons, those last two seasons haven’t been as fun as the season 1

I would have to agree with you Doretha. What I personally found as I continued to watch the show, however, is that it shifted its focus, and I was ok with that. Much like yourself, I’ve talked to friends who only watched the first season and thought the show was ruined afterwards. Again, the show revealed its true purpose following Season 1 (in my opinion at least), following a story that featured in Season 2 all the way until the conclusion of Season 4. While not as fun, as you mentioned, I believe the show began to teach from Season 2, particularly through Michael. Sorry about the rant, but I hope you understand!

I’m just frustrated about Good Place only having one Season in Netflix here in Finland. I would even go as far to pirate the other seasons bc I wanna see them.

It is really frustrating, indeed! In France, we are lucky enough to have the four seasons on Netflix, but there are other shows which are not available here, although they are in other countries.

I just started watching this show and i am done with season 2 right now. But the entire time I’ve wondered can shopping carts really kill you.

I have no idea, but I wouldn’t advise anyone to try, for obvious reasons! Plus, if it actually works “death by shopping carts” kinda lack of panache, I think! XD

Anyway, enjoy watching the rest of the show! I hope my article hasn’t spoiled you too much!

The reason Eleanor behaves more ethically and begins trying to become a good person at the end of S2 is because Michael alters the moment of her death and the near-death experience makes her reevaluate her life. She had absolutely no memories of dying and being in the “Good Place” because it happened in a different time line, so those experiences couldn’t have altered her moral intuitions because they didn’t happen to her. This also explains why she still behaved how she did in the grocery store and treated the environmental activist the same exact way. The change began after her near death experience.

You just got me to start watching it. I was presumptuously assuming it was corny and putting off giving it a try. It still a tiny bit but I like corny too and I like the stuff you dug into. Thank you!!

You’re welcome! Enjoy your watching! I hope my article hasn’t spoiled you too much!

Finished watching this show today, it’s so mind blowing. Thanks for the analysis.

You’re welcome! I’m glad you liked it!

I cried a lot on the finale, seeing they passing through the portal was so touching

I cried too!

Learing ethics is not going to work for everyone to become a better person, but it worked for Eleanor. Specially since she already had a predisposition towards getting better in the first place.

This essay does a really thorough job of explaining the philosophy behind the show in a digestible way–admirably, just like the show does! To that point, I think it’s important to address how well the show balances accurate education with entertainment value, as you point out. As the show itself says, it’s not as if everyone loves moral philosophy majors, but seemingly everyone I know who has watched this show likes it, which I think is a testament to the writers’ ability to take a hefty academic topic–moral philosophy–and distill it into tangible actions and relatable stories that resonate with people more than simply reading theory ever could.

Thank you very much!

I completely agree with you! The show is very well-balanced, and I think that it is what makes it so great! To me, great shows are the ones you enjoy while watching them, they entertain you, but, at some point, you also learn something from them. Thanks to them you learn things about the world or about yourself or even both. Because of that, great shows are the ones you can rewatch with the same pleasure, the ones that stick with you long after you finished them! Writers play, of course, a major role in that process!

Plus, I think that remembering ‘academic’ stuff is way easier when you can link those stuff to funnier, lighter, more common actions, words, situations, etc. Of course, you won’t get a Ph.D. in moral philosophy only by watching the show, but it can be a great way to gain interest in that discipline and even learn the basics of it!

The biggest crime in this tv show is the “Australian accents” the American actors put on – They are awful.

Well, being French myself, and despite watching the show in its original version, I still have a hard time noticing accents in what is, to me, a foreign language, but I’m sure it must be a bit annoying! … Like listening to a song you like played on an instrument that is out of tune? (I’m not much of a musician either, so I hope my metaphor is correct!)

I hope it didn’t completely prevent you from enjoying the rest of the show, though!

Well, being French myself, and despite watching the show in its original version, I still have a hard time noticing accents in what is, to me, a foreign language, but I’m sure it must be a bit annoying! … Like listening to a song you like played on an instrument that is out of tune? (I’m not much of a musician either, so I hope my metaphor is correct!)

I hope it didn’t completely prevent you from enjoying the rest of the show, though!

Wow! So much depth to one TV show. Amazing!

I agree! Though many shows can be studied through a philosophical view, The Good Place is particularly suitable and deep!

I feel like the good place and bojack horseman are like twins. different, but the same.

“The good place” is “The big bank theory” of philosophy

the sitcom actually has consequences and the plot changes each season i love b99 and the office but it’s too episodic

The show had a bigger philosophical impact on me as I went to film school in LA and we used to film on Universal Backlot quite a bit and the Good Place area with the frozen yoghurt and cafe is actually a little area on the backlot that they use as a European village or street. It’s been in tons of shows and films apparently. So as I’m in my midlife crises time watching a show about heaven based where I used to film many days while at College is pretty weird in and of itself. It obviously makes you take stock of your life just looking at it.

The morality of this show is very flawed! Why would buying magazines land you in hell? Whats wrong with magazines? Chidi clearly has a mental illness, he shouldn’t be judged on that.

Hi Thomas, I’m not sure if you’ve seen The Good Place in its entirety, but what you have stated is not the complete picture. The show goes into great detail about the structures and systems in-show that determine morality. Happy to talk about this further, if you would like!

Great show. LEARNING doesn’t do anything. APPLYING what was learned actually makes the difference. Knowledge in isolation is nothing and meaningless.

Doesn’t punch you in the face with philosophy though. Mostly just philosophy driving the story. So good. Constant twists and turns. Very good story.

Good place season 3 is extremely painful from a statistical perspective.

One of my favorite parts of the show, is that they not only have the brief philosophy lessons in the show, but the rest of the show actually subtly covers those same lessons (or in episodes without lessons, other philosophy concepts), increasing your knowledge on the concepts.

Loved this show

A really well researched and written piece! I adore this show, and although (to me at least) it wasn’t always a ‘laugh-out-loud’ comedy that I was expecting, it brought me both joy and perspective. Again, a really well written piece, thank you so much for sharing!

Well, you’re welcome! And thank you very much for your kind comment!

I agree, The Good Place is not always a “laughing-out-loud” show, yet it still does the job amazingly, being both entertaining and intellectually stimulating!

I haven’t truly gotten all the way into this show, and still have a long way to go, but I appreciated this post, and it’s re-inspired me to keep watching. In particular, I think what makes the show so interesting in terms of these questions is that, especially as a comedy, it doesn’t necessarily have to be a perfect assessment of any of these ideas, or a perfect representation of any one philosophical conclusion, just a space that encourages folks who otherwise wouldn’t care about them to ask questions about them as water-cooler talk. Would that more comedic media in particular were aiming for the same.

Thank you very much! I completely agree with you, and I think that this – this mix of comedy and philosophical seriousness – is what made the whole piece work so well.

I hope my article hasn’t spoiled you too much and that you’ll enjoy watching the end of The Good Place!

Nice connections among classical literature and contemporary media.

Thank you!

And thank you very much for your reviews during the editing process!

I loved the good place. You could have brought in about dystopian, reality vs non reality. The new series could have been good to talk about reality vs non reality as one of the new residents thinks she’s dreaming or something? Also could have brought in about dystopian and utopian themes and explored them.

I personally enjoyed watching The Good Place and fond that a lot of the theories touched on in The Good Place rang true in the real world, especially the idea that actions can be perceived differently depending on time period and social context

The Good Place was an amazing show because the topic was really interesting. The philosophy behind it isn’t a way the characters only connect, but also express how they see life, which is how a lot of us interpret life as a whole.

I am gushing, if only because I am a philosophy student and this is my cup of tea. Listen, I loved the piece, most especially the reference to Sartre and virtue ethics.

Here’s what I’ll say about it, though: I think the fact that virtue ethics is missing in the Good Place is slightly problematic. Virtue ethics focuses on ‘being’ a good person rather than ‘acting rightly’ (Rosalind Hursthouse wrote a great paper on this), and given that the whole premise of the show is that Eleanor wants to ‘become’ a better person, then teaching her how to act rightly is not sufficient to achieve this endeavour well.

But I think the mashup of ethical theories and views in this show is a perfect example of how difficult (and messy) trying to be good can be (and often is). It honestly does what it tries to do quite tastefully, irrespective of its shortcomings.

This is a really thoughtful article! The show does an interesting job at attempting to make the complicated world of ethics and philosophy accessible to wider audiences but I wonder what gets lost in the short, sitcom format… I kept wondering how a different genre might have handled the very fascinating and profound ideas this show was attempting to grapple with.

Can we assume there is a rational human for deciding what rules are acceptable? What about people that believe wholeheartedly in climate-denial or racism?

I like how the show strikes up these philosophical conversations. I think it’s good to talk about what comes after life on Earth!!

Phenomenal article Gavroche! Kudos!

There are actually many, many other philosophical concepts within the show. I will point one out, and will reply with more if anyone is interested (this is an older post).

Some other philosophical concepts encountered in the show:

1. The Problem of Hell (Philosophy of Justice) – They constantly illustrated the absurdity of everlasting torment for normal human offenses (e.g. flattening penises, lava down throats, etc, lol). By the end, hell not only seemed laughable, but completely absurd as a logical construct for reward/punishment.(especially in a ‘benevolent, or at least just’ Universe)

Anyway, I have many more. Such an amazing show! They definitely brought on top-notch and diverse Philosophy experts/consultants.

I love this show. Makes me think about all of this also. Great article.

When I began watching this I was hopeful. I found it to be disappointing and stopped watching it. It just wasn’t a good fit.