Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried: Using Fiction to Cope With Tragedy

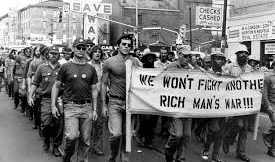

War stories are prevalent in our culture. We take them for granted with movies and TV shows and novels telling us how to interpret war and its so-called glory. War is not like that; war is not something that can be properly represented in its true horrific form for mass consumption.

By all rights and purposes I am about as much of an Army brat as one can be without a parent on active duty. With that knowledge one would assume that I would know much more about the military than solely the kinds of values instilled in my father, grandfather, and uncle over the course of their lives in the service. I do not actually know much about their time, just that being a soldier is a kind of sacred duty. In a culture that so readily glorifies war I somehow have never heard any firsthand account of what war is actually like – unless one is to count the fictitious military dramas that my father is drawn to watching in the evenings. In my junior year of high school Tim O’Brien’s novel The Things They Carried elucidated their silence on the matter for my curious mind.

The Things They Carried embraces the untellable nature of war experiences that I had never understood growing up. The book is written from the perspective of a character named Tim O’Brien who operates outside of the finite realm of author Tim O’Brien’s experiences and dances the line between fiction and truth to tell the tragic story of the Vietnam War in as true a manner as can be put onto paper for others to consume. The Things They Carried is as much about the act of telling a war story as it is about the war story and experience of the Vietnam War itself.

The Limits of Representation

The problem with the telling of the kind of story such as in the pages of The Things They Carried is that the very nature of war cannot ever be represented outside of having lived the actual experience. Fiction is the most accessible way of transmitting the untellable war story to those who were not there to experience the events: outside of actual involvement nothing can come close to recreating what it is like to experience combat. The nature of trying to represent such a traumatic experience in words automatically places limits on the event itself because of how easily the trauma diminishes with another’s interpretation. Something intrinsic to the experience gets lost in the telling.

By representing something in words, our system of language warps the depth of a feeling and an experience. W.J.T. Mitchell writes in the Critical Terms for Literary Study that “representation is that by which we make our will known and, simultaneously, that which alienates our will from ourselves in both the aesthetic and political spheres” (Mitchell 21). What one plans to discuss may not even be what one’s audience takes away from their words. Tim O’Brien does not shy away from this limitation of language and literature in the stories he captures within the pages of The Things They Carried; rather, he embraces and plays with the limits of memory and truth within the confines of a story to illustrate the difficulty that soldiers face when coming home from the contentious Vietnam War.

Establishing Credibility

O’Brien identifies a conflict within war stories themselves: that it is hard to tell the truth from what it is literally versus what seems to have happened. The depth of emotion and experience warps the ability to even provide a factual account. There is an opposition between experience and truth that is hard to overcome because the truth of an experience might not be true to the reality of the events themselves. O’Brien comes to the conclusion that because of this some stories are just beyond telling. The problem comes in the re-telling when one tries to go about recounting what they have just lived:

There is always that surreal seemingness, which makes the story seem untrue, but which in fact represents the hard and exact truth as it seemed.

This is the problem with trying to represent something this senseless and imperceptible – emotions as they were lived look pale and weak when recreated in memory and story-telling.

In the chapter called “How to Tell A True War Story” O’Brien provides the grounds of credibility for war stories as a commitment to obscenity. He says that any true war story cannot be morally charged or have some sort of higher truth because war does not function on a higher plane of existence:

It does not instruct, nor encourage virtue, nor suggest models of proper human behavior, nor restrain men from doing the things that men have always done.

War is gritty, bloody, and brutal. O’Brien posits that if one feels uplifted and encouraged at the end of a war story then they have been made victims of an age old lie that there is any goodness and glory and admirable things in a war. War stories have to frighten, embarrass, repulse, and unsettle the reader for them to be sincere representations of the actual experience.

A Hot Commodity

The soldiers participate actively in the commodification of their own experiences in trying to even make sense of them for themselves let alone other people. To even begin to talk about one’s war experiences is to make them something to be consumed and taken over by their audience for interpretation. O’Brien writes:

By telling stories, you objectify your own experience. You separate it from yourself. You pin down certain truths. You make up others.

To speak of these memories and stories in the form of a literary text, one can apply to the soldiers the idea of the exchange between author, text, and audience. Once the text has been created, the author has very limited if any control over the interpretation of the words. The audience consumes the text and creates meaning from it. This exchange emphasizes, “what the reader contributes to interpretation rather than what the text gives the reader to interpret” (Mailloux 124). The soldiers’ experiences and stories operate outside of themselves once told to other people.

This commodification is best seen in the story of two soldiers named Norman Bowker and Kiowa in the chapter entitled “Speaking of Courage.” The story describes Bowker’s tumultuous thoughts on meshing his Vietnam experiences with his home life. It elucidates a conflict between Bowker’s feelings versus how he thinks others will interpret them. Bowker imagines telling his father of the one medal he did not win in comparison to the seven medals that he was decorated with. Bowker is paralyzed by his feelings of cowardice for not saving the life of his friend Kiowa as he was sucked into the depths of a shit field for fear of losing his own life in the process.

Bowker is stuck on this one medal that he did not win and he imagines that his father would try to bolster him with talk of the bravery he must have had to win his seven other medals.

A good war story, [Bowker] thought, but it was not a war for war stories, nor for talk of valor, and nobody in town wanted to know about the terrible stink. They wanted good intentions and good deeds.

Everyone in Bowker’s life seems to expect him to have stories of courage and bravery that media portrays war with, but Bowker is crippled by his experiences and cannot mesh his life at home with the life that consumed him in Vietnam. The problem arises from Bowker’s sense of oppression by the commodity that his war life has become in relation to the rest of his life at home.

O’Brien says that in his telling of Norman Bowker’s story and Kiowa’s death he took pride in “shadowy, idealized recollection of its virtues.” His original efforts to tell Bowker’s story erased much of the true details to favor the progression of O’Brien’s protagonist – these omitted details most prominent being the field of shit that causes Kiowa’s death – and left out the truth of the experience. O’Brien sends a copy of the story to Bowker to see what he thinks and Bowker’s reply is described as being short and relatively bitter. Bowker writes to O’Brien and says that the work is “not terrible… but you left out Vietnam. Where’s Kiowa? Where’s the shit?” Eight months later Norman Bowker hangs himself. War becomes his world and once he is removed from that world it destroys him.

O’Brien rewrites the story with a renewed commitment to capturing the experience as it was. The problem with memory is that in retelling it one erases much of the flaws and fills in the gaps with what one would like to think had happened. The cognitive dissonances that arise from the horrible events experienced get resolved to make more sense and carry more purpose even though they never fully will. O’Brien makes a point at the end of the chapter to mention that details of Norman Bowker’s story are still O’Brien’s own creation, despite the previous pages of commitment to telling it as it happened and giving voice back to Norman Bowker after death.

The Whole Truth and Nothing But The Truth

The one thing that I have always known even before encountering O’Brien’s novel is that it is hard to tell the truth about war. Fiction provides that medium for Tim O’Brien to make sense of what he and his comrades lived through in Vietnam in the hopes that the war’s true reality will come across to his audience. O’Brien writes that his goal in creating this work is that he wants “you to know why story-truth is sometimes truer than happening-truth.” Stories make things present for both the author and the audience. The power of narrative is to impose meaning where meaning cannot, and in this case should not, ever be found. The power of literature is that it can do more for expressing the nature of reality than can reality itself sometimes. O’Brien writes that the truth of the man he killed is that there were many faceless mean that he could not bear to look at, but for the sake of story-truth there is one man that he killed who was a “slim, dead, almost dainty young man of about twenty.” For the feelings of all the faceless men that O’Brien saw and killed to be conveyed to his audience, the story must focus on one dead man; one instance of horror and despair drawn out of the reader. The story-truth is more true that way in the feelings that it conveys. Many faceless men do not carry the weight of one man’s face for people who have not and most likely will not ever experience war.

The Things They Carried tries to carry the indescribable weight of conveying memory and experience for the soldiers described within its pages. The novel takes up the task of their truths and lives in the form of “story-truth” to make the experience more real to the world that will never experience and never understand war. Some of the truth gets lost in the representation of the war; some of the lie gets conflated into weighing more than the truth. Sometimes though, the lie is more necessary to make people understand war’s senseless nature.

There is a culture of soldiers within our society living with a burden that no one except for their veteran and active duty comrades can ever fully understand, and it is the duty of fiction to try to bridge that divide. Tim O’Brien brings the outside world a little closer to the veterans living within our culture in the pages of his novel and shows us the power of fiction to impose meaning on our lives. Fiction is the only kind of truth that people such as myself can access. It is one of the most open means of understanding this huge portion of history, and of the lives of members of my own family.

War is a type of hell that no one, not even those who have lived and fought through it, can ever fully represent or comprehend, but fiction can help us close the huge gap within our culture wherein war lives and operates. We need stories like Tim O’Brien’s: to help us reach the unknowable subculture of war underpinning our society and to cope with the tragedies it leaves behind.

Works Cited

Mailloux, Steven. “Interpretation.” Critical Terms for Literary Study. By Frank Lentricchia and Thomas McLaughlin. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1995. 121-124. Print.

Mitchell, W.J.T. “Representation.” Critical Terms for Literary Study. By Frank Lentricchia and Thomas McLaughlin. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1995. 11-22. Print.

O’Brien, Tim. The Things They Carried. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009. Print.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I loved reading this in 400. It’s certainly not a genre I would have approached before in my life but it was very enticing. My favorite section is definitely when he writes about Rat’s girlfriend in Nam. (or was it Rat’s story about someone else’s girlfriend?) Great article!

Thanks so much! I definitely agree – if it weren’t for my junior year in high school followed by a couple classes at SMCM that tackled this book, I doubt it would have ever crossed my radar.

I enjoyed reading this piece very much. My son served as a Marine in Iraq and there are things he will never tell anyone. I like the insights you give in your analysis of O’Brien’s work and the points you made about the inability to convey the reality of war is impossible. I also like ynour point about fiction facilitating the means by which readers can get some sense of the truths regarding war. Thank you for your clear and thoughtful explanations.

Thank you so much! That means a lot!

I feel that he writes as if it was a poem because the discrption oh what is going on in the book is so well stated and couldn’t have been stated in a better way. What I really like about the book was the ending because in the ending he describes how he brang everyone to life and is speaking to them. For example, he speakes to Linda which was his girlfriend back in the day when he was about 9 years old. He is speaking to her.

What was really unique about this book is how the author switches from 1st person to 3rd person. I liked that because it showed who is speaking and what is that person thinking about the situation.

Thanks for your comment! I definitely agree with you about the PoV, I think it’s part of what makes it so unique and compelling.

While I did enjoy reading this book… I simply wish to note, though, that this book fails to see the bigger problems of wars. As the author would claim, it is not the soldiers’ fault that they are forced to kill people on foreign grounds. Rather, it is the government and the leaders’ fault that they violated individual human rights of the soldiers. Such soldiers are forced to commit murder under the barrier of the justified reason: “protection for our nation.” Ironically, the people in Vietnam simply sought protection and possession of their land and themselves. That is why wars must end—because all warriors are innocent man with proper reasons.

I definitely agree with you, and thank you for your comment! It’s important to point out limitations like that because they are incredibly important to the reality of things in our country.

Honestly I find some parts of the novel even similar to a propaganda.

Which parts, if you don’t mind me asking?

Okay, I really need to stop judging books by their cover. I just can’t help myself. I was expecting some more action and gruesome puddles of blood, but reading this opened my eyes to a new reality. You can see a lot of human emotions displayed on the characters’ faces. Guilt, sadness, curiosity…This is not a book for naive people. There is cussing and intentionally crude ideas. But you’ll be walking in the heavy boots of many life-changing men.

Chism

Thank you for your insight; I agree wholeheartedly. The emotion is honestly more haunting at times than I think any amount of gruesome violence could be. At the core of the bloodshed, war still involves very real people on both sides. I think that’s why this book has stuck with me for so long.

This book is life-affirming, in a painfully paradoxical way.

I agree with you entirely. I think more people should read it for that reason.

Personally I didn’t know much about the war what so ever, but while reading this book and reading about the characters stories and what the had to experience all of that, I was very intrigued.

That was what drew me to it in high school when I was first introduced to the story. Thanks so much for your comment!

Reading this certainly made me think. I’ve always been a believer in the power of words and their ability to express absolutely anything, but I see now how there are some things that simply cannot be written to mirror the true experiences someone has gone through; I’m not sure if I view this as a good thing or a bad thing.

Nor am I, if I’m being entirely honest. Discussions with friends and professors about this book have left me questioning a lot of things I used to hold as 100% true. I think there’s something to be said, though, for pointing out the limitations and using that as a jumping off point to express those inexpressible things.

The way O’Brien use of metafiction as catharsis specifically in the context of war and its aftermath is really interesting. I think you explored well the author’s depiction (of the depiction) of war as an art aimed at understanding. Thanks for the article!

Thank you so much!

This article is very insightful when it comes to discussing how “true” fiction can be at properly conveying an experience rather than an event. I loved reading this book my junior year in high school although I never quite knew why I was so drawn to it until now. There is so much to learn from the act of story-telling, especially through traumatic instances like war. Great piece!

Thank you very much, that means a lot! This book has stuck with me since high school as well, and I loved discussing it in college courses because I finally saw why. It’s incredibly powerful.

O’Brien’s book handles the double-edged sword of representation well. And his bit on the story-truth being more real that the truth is great. Good article!

Thank you!

I read this piece in my Trauma and Contemporary Literature class I took last semester so I totally get everything you’re saying. It’s a wonderful book and you did a great job expressing what it does in your article. Nice one~

I’m so glad people are still reading and talking about this novel 24 years after publication. My father served in Vietnam and like your relatives never revealed anything about his service. This novel made me feel closer to him and his experiences by the end, which I can say of very few books.

There are definitely varied ways of telling war stories, especially on something as charged as the Vietnam War.