Why Is Utopian Literature Less Popular Than Dystopian Literature?

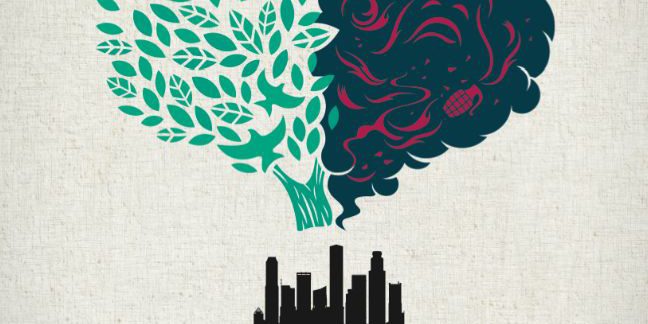

What is the universal fascination with books or television or movies that depict a negative, corrupt, dystopian society? Is it perhaps the ability for readers to relate better to a broken world rather than a perfect one? Or is it the impact of modern day society on our perspective of what a “good” world is?

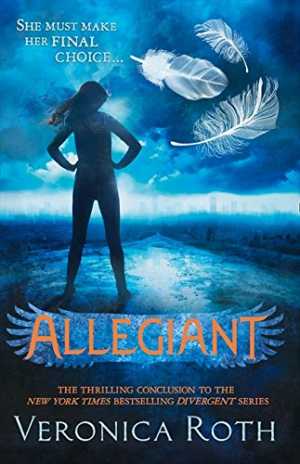

Dystopian culture is a prominent setting in many young adult novels today. From authors like Veronica Roth to George Orwell, the dystopian world has been a popular one for writers to explore and for readers to experience for decades. But why is it that we become so enraptured in these unpleasant, fearful dystopian worlds?

One proposition for the reasoning behind why dystopian novels fly off the shelves could be because we are knowledgable enough as humans to recognize when our world could turn into the world in which we’re reading about. The possibility that our society could become run by a tyrannous dictator, or that our choices and freedoms could all be stripped away are real possibilities, now more than ever. Now, when it feels like the Earth is dying, and animals are dying, and humans are dying because of unknown viruses is when dystopia becomes so much more relevant. Suddenly it feels like these worlds that have been imagined up could actually happen. Humans could become desperate, and start rioting, the government may become extremely controlling, democracy could cease to exist, etcetera.

So in reading about the types of settings like in The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood or in Divergent by Veronica Roth, or even 1984 by George Orwell, one can begin to envision the possibilities of the future, and therefore mentally prepare oneself for the destruction of the current world. One thing humans seem to like to do is to prepare. Whether that’s stocking up on canned goods, layering sandbags outside the house before a storm, or boarding up windows, we’re always prepared for the worst. And so perhaps dystopian stories – where destructive, unpleasant, and scary worlds are depicted – help us prepare for what seems could be possible in Earth’s future.

Furthermore, the popularity of dystopian novels could be due to one wanting to feel grateful for the world today, and these dystopian worlds remind one of all that is good in the current society. Perhaps I’m giving humankind too much credit here, but this could be a possibility. Think about it: would you feel more gratitude for the freedoms we have today if you read about a world in which women are forcefully impregnated to populate the human race, as in The Handmaid’s Tale? As a woman, I know I appreciate my freedoms and my rights even more after reading that novel. But maybe this isn’t true for everyone. Perhaps one just enjoys reading about worlds in which people are submissive, and fearful, and abused, and powerless because that is what is interesting. In that case, there still must be a reason why these aspects of a world would be interesting, right? This brings us to another reason: the characters.

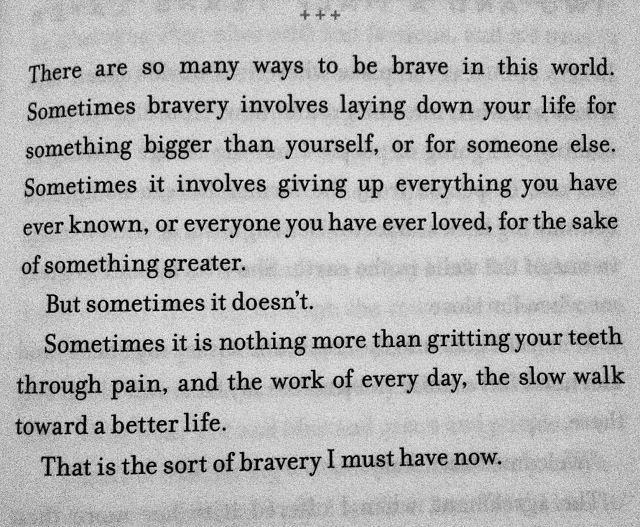

Maybe it’s not about the dystopian world at all. Maybe it’s about the development and growth of a character and the traits exhibited by them in this unpleasant world. Perhaps reading about how Tris kills herself for her traitorous brother in Allegiant by Veronica Roth makes one want to be a more selfless person. Is reading about her bravery and selflessness inspiring? Or, maybe one can relate to her character on a deeper level because being selfless and brave in dire situations is who you are.

Looking deeper, maybe reading about Tris’ act of bravery and selflessness for her brother teaches the importance of family, and how strong familial love can be. Either way, readers may enjoy dystopian stories for this reason. Seeing characters exhibit traits you have or wish you had is inspiring, or enables one to relate to them on a deeper level. Because let’s face it, how many characters are you going to see act as brave or as selfless as Tris in a completely utopian (ie. perfect) world?

Onto another idea: do we read or watch dystopias because of the eventual utopian ending? Maybe we’re suckers for a happy ending, like every childhood story we grew up with. Even though transforming a whole corrupt world into a more positive, less corrupt one is more complicated then a superhero saving the world and all of a sudden it’s sunshine and rainbows, the evolution of this dystopian world could be what interests readers. It is the final chapter, the final book, or the final episode where everything is okay again that one looks forward to; it is the reason one endures reading or watching all the hardship of the dystopian world. Otherwise, why would one read about experiences of human pain or destruction? It is the eventual ending that is exciting, and that causes readers to think, “maybe everything will be okay” or “our world isn’t that bad”.

All in all, there is no denying the popularity of dystopian stories. It is interesting to divulge the possibilities for why one would enjoy these horribly corrupt settings, like for mental preparation if Earth turned out similarly, or for character development, or for the eventual utopian ending. Maybe none of this is true, and maybe one just enjoys dystopia “just because”, but subconsciously, one of these reasons might be the cause.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

You could check out Iain M Banks. He writes some nice Utopian sci fi. Kim Stanely Robinsons Mars Trilogy is an even better starting point in some ways because it’s basically a primer on utopian theory through the ages.

There’s a bunch of other utopian sci fi novels. Herland, looking backward, etc.

To my mind utopia will be based around technology erasing work and a lot of the day to day running of society. Venus project is a utopian organization though I haven’t looked at them in awhile. There are also agrarian utopians but most of them seem to be drawn to the past for Utopia and when it can only exist in the future.

Lastly conflict isn’t eliminated. Humans are going to disagree. However when these disagreements move from armed conflicts to an acrimonious exchange we’ve made progress. Not to mention the scope of these disagreements shifting. Take for instance any close knit society the thing they disagree on to the outside may seem minor but to them those splitting hairs are what matters. My point is we will all disagree and there will be conflict.

I’ve not read Ian M. Banks, though have been meaning to, thus thank you for the reminder in commenting on him. I have tried Red Mars by Kim Stanley Robinson (I’m a very big fan of science fiction!), and oddly I never seemed to get too far into it, albeit that was long before I did my English degree and in a time where my literary tastes lacked refinement. I do mean to read the trilogy some time, as it’s a concept I’m greatly intrigued by.

There’s certainly societal conflict in it. My memory has faded in regard to it, but I believe there was a terrorist attack of some manner that takes place. Would one be inclined to consider it a utopia given such? Or at that point of extreme conflict then label it as a dystopian? Curious actually, where we would draw the line, on utopia. After all, stories require some kind of conflict. Though I suppose for the purpose of argument it probably would be considered a utopia but one that has devolved into a dystopia. I will need to read the entire book, I think, to find the answer to my own question. Or maybe it’s a utopia that struggles to fight dystopian forces, and returns back to its former utopian state. That is certainly one way in which you could write a utopian story and I’d never thought of that until writing this comment. Very curious thought. I will have to think on it more.

I suppose one could write involving interpersonal conflict, and still have the utopian vision endure. In fact, when I google dystopia, for the writing of this comment, the Cambridge Dictionary suggests “a very bad or unfair society in which there is a lot of suffering, especially an imaginary society in the future, after something terrible has happened”. Terrorist attacks would certainly embody that. So while the world of Red Mars may be at least initially utopian, it seems the conflict therein would be evocative of a dystopian. Of course I’ve only ever read the first 80 or 90 pages, so please ignore me if I’m incorrect in my statements regarding it. Perhaps I will make it a point to read Red Mars some time soon.

Now you have compelled me Elene to think about this more, and also reminded me to try reading Red Mars a third time, as a more mature reader.

Fiction actually does have some societies that are neither completely dystopian or boring. Most Neal Stephenson books would fit, as well as many other books based on the ideas of Rational Fiction.

I like complex societies depicted in fictional literature. I don’t want the world to be rid of all problems, and thankfully it doesn’t look like that will ever happen. Suffering may decrease, but there will always be work to be done.

But if there is work that needs doing, does that mean that the society is indeed not perfect?

Today’s society is indeed not perfect. Future society will not be perfect, but society then will be better than society now. There is no end-state where we have “won.” In fact, that is the wrong way to look at it. The right perspective seems to come from Finite and Infinite Games. In it, James Carse mentions that “Only that which can change can continue.” The world where we have succeeded in creating a utopia is boring, because it cannot change. The final goal (creating a utopia) would have been accomplished. But the story ends there.

It’s preferable to have a complex society because it isn’t static. Complex societies don’t have to be 1984-esque dystopias. Dystopias are even more limiting than utopias. Complex societies allow for problems, but (hopefully) don’t allow for them to grow to the point where they make society static. Nothing happens in a society where everything is already perfect. As you said, it is boring. But a society that has been destroyed by plague is worse than boring -it’s nonexistent. I don’t want to optimize society for happiness, not totally anyways. I want a society optimized for interestingness. Something that will allow people to do meaningful things, but still have a relatively comfortable life.

This has been a major philsophical concern for me if that if huamnity was to somehow achieve utopia and learn everything there is to know about curing disease and everything, in a “perfect” society what would we even do and how would we live. I guess you can say I am nihilistic and pessimistic about the future and concepts like utopia and transhumanism I typically see nothing good that can come out of it. But then I wondered why are we even trying to improve if perfection is not a good thing.

Well, the fact is that a dystopian society, and the conflicts that arise from it, is a pretty damn fertile ground to tell a story,

And it is so, because it’s really not that far fetched. Technology is advancing far faster than we are as a society, and this is something that we all instinctively know.

Movies and books often cater to the threat of the month or year. Most (North American) movies in the 80’s and early 90’s had some sort of direct Russian or South African threat. Then it moved to the Middle East threat. But through all that and well before, yes, that dystopian theme keeps popping up.

Our technology is maturing faster than we are, and deep down…. we know it.

There were American movies with South Africa as the bad guy? The Power of One is the only movie that I remember seeing in the US back then that had South Africa as a major theme. That and District 9 are the only non-documentaries featuring South Africa I can even think of and District 9 was way later.

Were the generic terrorists from Steven Seagal and JCVD movies all South African and I forgot?

Lethal Weapon (or one of them) had South African bad guys

I think all fiction is a way that we use to flesh out ideas and emotions that we cannot experience. We all recognize good art because the artist is able to share and convey their experiences and thoughts and ideas and emotions through their chosen media.

Reading dystopian fiction allows us to put ourselves in dangerous situations that we won’t ever experience, allows us to explore what good and evil and all the grey in between is and where we fall in it. It helps us develop and test our empathy.

One thing dystopias do is project our deepest fears about ourselves. It gives us a thing to point to and say “OK we know that’s not where we wanna go, how do we avoid this”

Utopias are impossible because reality is never perfect, it’s a hodge podge of getting things to work just well enough to survive.

A life with no suffering is bad, it makes weak people who turn hedonistic. They’re basically over grown children with no concept of responsibility..

What’s wrong with hedonism?

Dostoevsky had something to say about this in the second half of The Underground Man.

Basically, we are shitting ourselves if we believe we actually want a utopia. A utopia would be a tragically boring and logical place. It would be the end of our ability to express the side of us that is not logical and reasoned.

The side that cannot be confined in a world based on facts and numbers. That is, our instinct, our wildness, our desire for the ‘rush’.

So we tell ourselves that we want our tech and our science and our atomism to move us towards this peaceful utopia of no suffering. But we are full of shit, and will smash the machines that move us there whenever we get too far along the road. Of course, then, we lament the destruction of that which would have brought about our supposed goal.

Because utopias don’t make great settings for a story. The closest you will get are societies that seem like utopias with some hidden dystopian truth lingering underneath.

Or utopias where the characters leave the utopia to interact with the less fortunate societies. E.g., Star Trek.

What about just “topias”? More or less like in the film “Her”, where the future is depicted as different, with good and bad things, but normal in a way, just different and more technologically advanced.

Which is why Star Treck TNG was so slow to get good. In the early seasons, they were constrained by a utopian vision that was so extreme as to forbid conflict.

Honestly, a Utopia should have no interesting stories. Even in mundane, down-to-earth genres (e.g. not “Save the Universe from an evil alien”) stories are usually the result of major fuck-ups. Even something like a bad relationship (start of most rom-coms) really shouldn’t exist in a utopia.

Brave New World is actually about an utopia shown as a dystopia.

Humans there are very happy (thanks to medication/drug), I don’t think there were any wars. People had very different values, children had sex growing up IIRC. But in the end everyone in the normal society was happy. I guess there’s dystopian truths in there, but it’s still an utopia that seems like a dystopia.

Honestly, dystopias sometimes evolve out of what was once supposed to be a utopia (or have aspects that are seemingly utopian but obscure the marginalized or government influence). Uglies by Scott Westerfield is a world where everything is provided for the citizens of the city and they are entrenched in a system where they happily anticipate a day of heavy cosmetic surgery – of course, once you reject this system, the dystopian reality sets in. The Minority Report by Philip K Dick is a utopia where all crime is preventable through precognitive predictions but then, when our main character is predicted to commit a crime, the corruption of this ‘utopian’ system starts to come to light.

It’s a pattern that I really love, looking at ways to fix massive issues within society and then exposing how these fixes are abused and corrupted by the people in power taking advantage of it.

I think in many cases these books are taking modern trends to their logical, albeit often extreme, conclusion. In a lot of ways the future is looking pretty bleak right now. Also, heavy subject matter is more likely to get an emotional response out of your audience. It creates awareness and serves as a warning for things to come if we don’t act.

I think if you look at sci-fi written earlier in the 20th century you find much more optimistic/utopian futures portrayed, but as time goes on we see sci-fi become progressively more dystopian… as people actually started to get a taste of the future they started to realize it was darker than anticipated, and the writing reflects those observations.

I was once told that after major tragedies and disasters art in general respond with dystopian themes and, on the other side, superhero themes.

This is a great topic to discuss in 2021 and interesting analysis of it.

I always thought dystopian societies felt more likely than utopian ones. Although what separates utopia from dystopia can be blurry.

Most dystopian societies are really just flawed utopias. The fact that they’re set in the future just adds to the appeal and natural relevancy of the medium. The goal is to understand: what’s this future like, what went wrong, and how do we learn from it.

Consider Gattaca: a dystopian movie where genetic engineering has been taken to the logical extreme: eugenics. We clearly see all the good that can come from the technology but are also told about the downsides and dangers via the plot, which I won’t spoil.

Another example is 1984. Everything is controlled by the government—represented by the possible figurehead that is Big Brother—and there are two other super-nations alongside the one our story mostly details that constantly ‘engage in warfare’ to maintain the balance—and by extension, the stability—of each other, and yet, they’ve eliminated many of the struggles we go through even today. I’m really glossing over that book/movie, but the same idea applies.

Pretty sure anyone who lived more than 50 years ago would regard this as a dystopian future. The future is, by definition, foreign to us even though it makes perfect sense to its inhabitants.

Envisioning a functional, realistic, and interesting society more advanced than our own is incredibly difficult in comparison to just taking our own society and imagining it smashed to bits.

Because conflict makes for interesting stories and a utopian future would have less conflict to take interest in.

The only conflict-free stories I’m aware of are young children’s stories.

Ursula LeGuin said that if you take all the violence and betrayal out of kiddie lit you wind up with Johnathan Livingston Seagull.

It is like a movie theatre, everyone gets in the seats, the movie plays, and everyone leaves again. Boring. But the movie could have been exiting, interesting, depressing, or whatever.

At least to some extent, utopias are a kind of receptacle for the actual thing, the receptacle isn’t really intended to be interesting. If the whole thing was the receptacle, it’d either be boring, or unpredictable, and unpredictable-ness would destroy the system of society. So for it not to be boring, it must have a lot of flexbility about what it contains.

On the other hand, personal and interpersonal development probably don’t automatically go the right direction, i.e. it could go dystopian directions, so the receptacle does kind-of interact with the content, unlike the movie. In the movie theatre analogy, basically how the movie gets chosen is one interaction.

Finally, using a system, it is probably impossible to entirely contain all the developments possible that would jeapordize the system somehow. I.e. seems like you depend on the judgements of the people in it. Infact, i’d say that such a system would weave tight social networks, and keep attitudes in check so that the judgement is at least somewhat trustable. But it’d also avoid single points of failure.

Of course, there is the concern of conformity monoculture. Although i don’t think that is necessary for good judgement at all. Also, perhaps a lot of internal contradictions could play themselves out in games, allowing them to exist without real actual damage.

You should check out the Culture series of books by Ian M. Banks. I’m only on the first book so far but it’s pretty interesting. It’s not exactly a perfect society with no conflict but I would still classify it as a utopian society.

A “utopia” for some is inevitably a dystopia for others. And vice versa.

Because Utopia has to satisfy subjective, changing tastes and therefore cannot be static, or described comprehensively in an objective way, by definition.

There is such a diversity of drives, passions, interests and ways of looking at the world that any Utopia would have to be an imposition of one of these on everybody. It would require some sort of extreme oppression of the majority to get the utopia of a minority or flat out extermination.

Exactly – utopia equals totalitarianism. To vouch for a utopian ideal is to believe with utter certainty that one way of life can and should dominate over others, and that all opposition to such must be extinguished.

It’s hard to write about this. It’s hard to even think about it. There are so many factors involved in crating a society. If society was created from the top down, it would end up fairly simple. But we all play a part in shaping our civilizations. We have different goals, different skills, and different ways of thinking.

The best way to imagine a realistic future society is to look at today’s trends and forecast from there. This has limits, given diminishing returns and regression to the mean, but it’s a start.

Basically, humans are so used to struggle for survival that they won’t know what to do when there is nothing to struggle against.

Thanks for these thoughts! It’s definitely an interesting question. Genres are always practices of labelling and categorizing, and to an extent, the popularity of a genre relates to how much exposure it receives. As you point out, there are often utopic elements is dystopic works, so how do texts get shuffled under these different umbrellas? Because more readers have heard of dystopia, publishers might be more likely to market work under that label to attract readers.

Personally, I think that many of the roots of dystopia come from after World War I. Prior to WWI, Western Civilization was fairly confident in the direction that it had undertaken up to the war’s start. The aftermath left Europe and the Occident more broadly confused and unsure of where to go. These conditions lead eventually to the proliferation of escapism and dystopia literature, which increased the more the cultural milieu felt lost. Just some food for thought.

I tend to think the future is going to be very bright.

“Mental preparation.” That’s it in a nutshell, I think. And because dystopian literature tends to present the worst-case scenario, I think we comfort ourselves with the idea bad things can happen, but not *that.*

Dystopian is more interesting than Utopian. It’s as simple as that.

Today it seems easier for people to imagine a dystopian future than a utopian one. Are we simply too aware of the violence other humans are capable of? Or our fundamental inability to cooperate? Maybe. However, popular imaginings of the future used to be very optimistic, imagining flying cars and colonies on Mars, peace on Earth, etc. I’m curious as to why we have collectively shifted from imagining a Jetsons-esque future, to imagining a future in ruins.

Oh how I would love to write on this topic myself.

A comparison to the news media, for instance, offers a great insight into this. Why is it that we gravitate toward the negative, to bad news stories? It is because of the conflict. The strife. Utopian story telling, one might say, is bland. Where is the conflict in a utopia where all is perfect and good, for instance?

When the two towers fell, I was only a young teenager. I was GLUED to the television, to the news. The shock. The awe. The horror of what had happened. The media thrives on fear and they had me enthralled by it. Thus, so too does dystopian story telling. It’s about the struggle to endure. The struggle to survive. The conflict in a world rife with strife and disorder. This manner of storytelling thrives because it induces in us that emotive response that pulls us in. That fear response. You crave to know more. Thus, you are hooked!

We may also consider social media, in the context of the fear driven intrigue above. I read an article recently (I can’t recall where, alas), that talked about how Facebook had an algorithm for bumping up top comments. As it turned out, the top comments were those that created conflict and argument. Divisiveness sells. Fear, hate, anger, and group think, all sell. If you can entangle people in a raw emotional way, you can lure them in. You can hook them.

Thus, by tapping into our primal faculties, dystopian stories are able to use these emotions against us in their subtle exploit to harness the power of fear.

Regards,

Joshua Lee Topple, B.A. Honours English graduate of Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia. This site came to my attention courtesy of my good friend and former professor of Astronomy, Douglas Pitcairn, who received an email regarding it. I enjoyed reading the above article, and thought to write upon my own ideas concerning this topic, as I don’t have as much occasion for intellectual thought or writing, being out in rural Nova Scotia, these days.

Josh, consider joining us as a writer.

A suggestion which I shall certainly contemplate upon. I moved out to the country to work on a farm several years ago. Another month or so and the season is over and I’ll have some time to stretch my fingers and dust off my typewriters.

This article moves me to wonder what “utopian literature” is. Most settings that seem like utopia are really dystopias in disguise – for example, The Giver, by Lois Lowry, focuses on a young boy discovering that the idyllic world he lives in is very far from ideal.

The world of Star Trek is described as a “post-scarcity utopia”: there is no currency and considerably less war over resources. Yet the show is still known for its warrior races and weapons because conflict is inevitable.

The question “Why is utopian literature less popular than [anything]?” seems misleading because it assumes that there is such a thing as utopian literature.

Whenever I think about the concept of ‘Utopia’ I’m always taken back to the short story ‘The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas’ by Ursula K. Le Guin. I’ve read it a couple of times and I feel like it really underpins the reason why many people don’t think about utopian stories or even believe a ‘good’ utopian story could exist – it’s all a lie in the end.

Utopias feel, in theory, like the world equivalent of heaven I guess. Everything is fine, people deal with everything in all the right ways and everything comes to a nice resolution and no one gets hurt. But that concept of utopia has often been the basis of many dystopian stories because, in reality, someone is always suffering.

One person’s ideal world often is the antithesis of someone else’s expectations. So mitigating the differences, actually building a utopia, doesn’t seem possible. Is a world either utopia or dystopia? Or is it more of a spectrum, and if so, when does a utopia fail to be so? How much conflict is enough conflict? Where is the line drawn?

This is exactly what I was thinking. We study early on dystopias have similar characteristics to utopians and in some cases, it is hard to draw that line. Thinking of Elsewhere and the peaceful society in ‘The Giver’ that was my Grade 8 novel study the population all had a place to live, food, and family it was by all accounts the perfect world we are trying to reach now. But without an understanding of pain, we could be unknowingly cruel (Euthanasia spoiler here). To get to the point of equality and happiness that this fictional society reached while keeping our humanity we have to sacrifice and be willing to deal with the problems and complexity it creates. There is no perfect moral system but ignorance is not desirable either.

The popularity of dystopian literature originates from the fact that it’s easier for us, as disillusioned people, to envision the nightmarish and disastrous scenario than an idealistic and utopian one. It was in the 20th c that dystopian literature came to fruition, an era brimful of unprecedented cataclysmic events, such as world wars, which disillusioned people and smashed their idealistic perspectives. So after centuries of conceiving of a better idealistic world, people eventually came to the realization that a utopian world is impossible to achieve, for utopian ideals will eventually turn a society into a society. I guess French Revolution is the best example of such a perspective, for such attempts at creating an idealistic society, far bringing about a utopian world, ended up constructing a hellish and dystopian community.

I agree with the point that even through a dystopian narrative, we are looking for the final climax that’s utopian or at least convincingly “good” in the end, or a world on the mend, something like that. In a utopian narrative, that hook is missing. We need a hook for any type of narrative, and in a utopian work, for example, we know where it will start from and end on. We also know that it’s not likely to go from a utopia to a dystopia in a narrative.

I think another reason for the proliferation of dystopia in literature is the unachievable and drab prospect of a perfect world. If a world is perfect, there is not much of a story to be told (unless as you wrote, it is a journey toward a utopia only reached at the end). The only story one can really plot out in a utopia is one where a perfect world is revealed to not be so perfect. But this article did reinforce that quite funny idea that we only want to read about bad stuff. If it is good, we find it boring!

Personally, I would much rather escape to a utopian story than be shocked by how closely a dystopian story resembles real life.

Personally, I’ve always found dystopian fiction appealing due to my anxiety. Growing up, I’ve always feared the future to an extent, mostly because of all the traumatic experiences that I had not underwent yet (I.e. losing a loved one, getting fired from a job, heartbreak). To me, a dystopian story was like a horror story tailored to people like myself, as it toys with one’s fear of the future and dares to ask “What if we, as a society, screw up in the future?”

Very interesting read. I agree that humans love dystopian novels so much because it seems more plausible than utopian novels. Most people don’t enjoy stories where everything is perfect the whole time, because then where is the conflict? Conflict is what drives every story, it’s what engages the readers. A story with no conflict, or “lame” conflict is not going to grab most readers attention.

I think, in a way, we enjoy seeing how these seemingly perfect worlds fall apart– we like to see the imperfections of other societies so we can appreciate ours more. Take “Harrison Bergeron” for example, it’s a very popular young-adult dystopian novel. In this novel, everyone is equal, nobody stands out, and nobody is gifted in any area of life. To ensure everyone is equal, their society handicaps those who stand out: anyone who is strong must wear weights, anyone who is pretty must wear masks, anyone smart must wear transmitters that disrupt their train of thought every 20 seconds. When we read that, not only do we appreciate our freedoms, but it reminds us to appreciate our individual differences. It opens the story up making it seem like it’s the perfect world everyone wanted– never having to compete with each other– and then shows the harsh reality of their quality of life. It shows us all of these horrible futures that aren’t too far fetched and then says “nah, I’m just playing. But, what if…?”

A few years ago I began reading Kim Stanley Robinson and others who are often labeled “utopian.” As a reader and and writer who was always drawn toward dystopian works, it was an eye-opening experience. Dystopias are easier–easier to imagine, easier to believe in, even easier to write. But we need utopian stories now perhaps more than we ever have because whether we want to admit it or not, the stories we consume shape our worldviews. How can we survive our increasingly dystopic reality is we haven’t learned how to imagine something better?

I think the idea of dystopia always seems more realistic, more reachable than any kind of utopia. Not only is it the knowledge that political and social unrest will never cease, but also the individualistic hope that we could ‘survive’, that we could build our way to a personal utopia in the face of dystopia.

I definitely feel that people relate to dystopian societies more. Plus is it really be possible to create a utopia? What would even be left interesting in a world that has no problems?

I wouldn’t say that people like to prepare for the worst. They like to panic and most of the time their actions occur too late. Stocking on canned food and toilet paper is not getting prepared; it is panicking and reacting out of proportion to a situation they weren’t prepared for. But I agree that people are usually fond to dystopian stories because those stories are actually closer to our realities worldwide.

All the suggested explanations makes some sense to me – except for the last one. Does not the addition of a utopian ending subtract from the merit of a dystopian setting? Does the utopian (=’happy’) ending not render the whole narrative less convincing, more shallow and less complex, because it suggests to the reader that all the preceding hardship and desperation was, after all, based on a false or misleading impression? Personally, I have tossed a book across the room once it became clear that it was about to end in what felt like sugary platitude in contrast to all the shock and struggle that preceded its – which were the reasons why I enjoyed the read up to that point. A real-world counterpart is the reality of climate change and the myth of ‘green growth’ as a suggested solution.

I definitely think that it’s easier to relate to dystopian just because we can all generally agree what makes a terrible world. Famine, sexism, pain, grief, etc. But it’s much, much harder for people to generally agree on what a utopian world would look like since everybody prefers different things. So what one reader might find they enjoy in a utopian, five other readers might find it boring or uninteresting or just not utopian at all, thus harming the reputation of the entire genre.

This has always been interesting to me. Especially the way that social minorities tend to drift towards more of these stories in their youth – speaking from personal observation.

I also think it could be a creation of Utopia itself. As some comments state: it’s hard to imagine a Utopia setting because everyone thinks of something different, but everyone can agree that when conditions are terrible (war, famine, etc.), what comes after is usually Utopia-like. When you think about it, do these characters actually get a bright and happy ending? Or are they just free from the constraints of a broken world?

Everyone has different ideas of what is freedom and happy endings.

Especially the way that social minorities tend to drift towards more of these stories in their youth – speaking from personal observation.

I also think it could be a creation of Utopia itself. As some comments state: it’s hard to imagine a Utopia setting because everyone thinks of something different, but everyone can agree that when conditions are terrible (war, famine, etc.), what comes after is usually Utopia-like. When you think about it, do these characters actually get a bright and happy ending? Or are they just free from the constraints of a broken world?

Everyone has different ideas of what is freedom and happy endings.

Hi Alyshabuck! Thanks for the article, I’ve been struggling with the same question. As a writer, I hope to find a way to make utopian fiction work in a way that has mass appeal. Of course, there have (and are) writers working within the utopia genre, but I can’t think of a single film adaptation based off one of these stories. Typically, the closest we ever get is a utopia that is ACTUALLY DYSTOPIAN?!?

I think you hit on some good points of what makes the dystopian genre appealing. I think it would help your writing if you took those opportunities to contrast it with the utopian (very little time was spent looking at utopias themselves). What kinds of conflicts are going to arise for characters within a utopian setting? What does a utopia actually look like (without being ideologically presumptive)?

I suspect that with the rising popularity in cottagecore/cozy fantasy, we might see a counterpart in science fiction (ala utopian science fiction). These might look more at the troubles intrinsic to the phenomenon of love, without the clichees attached to the romance genres like financial gain via marriage, or trauma bonding.

Looking forward to reading more of your work!