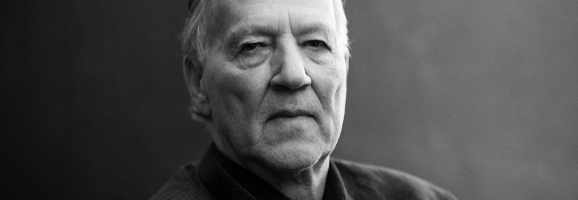

Why We Need Werner Herzog

The criticisms of conventional Hollywood cinema have been repeated again and again – commercialism, predictability, lack of genuine humanity. But apart from sappy romantic clichés and tough guys walking away from explosions and not looking back, there’s another extreme: that of the self-important art-house auteurs who alienate audiences with inaccessible symbolism and false profundity. In a medium rife with different forms of artifice, it is rare and remarkable to see a filmmaker who tows the line, never trying to numb the audience with empty spectacle, or deceive them with pseudo-intellectual nonsense.

François Truffaut called German auteur Werner Herzog “the most important film director alive,” a statement far from unfounded. Herzog possesses a unique ability to make bold, visionary works of art that stray far from the mainstream but avoid any kind of superiority over the audience. For a man who has given us images of dwarves carrying around a crucified monkey (1969’s Even Dwarfs Started Small) and seemingly arbitrary footage of an old man with thick eyebrows in a Mongolian marketplace (2009’s My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done?), he doesn’t come off as pretentious.

In a career spanning from the 1960’s to the present day, Herzog has looked upon the world with wide-eyed wonder and appreciation. Rather than manufacturing things, his career has been about capturing them, his camera becoming some sort of divine net. As one who has devoted just as much of his career to documentaries (such as the acclaimed Grizzly Man) as to narrative cinema, such instincts have carried over into his narrative films.

The repeated casting of eccentrics such as the volatile and prolific actor Klaus Kinski (Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Fitzcarraldo, others) and mentally ill street musician Bruno S. (The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, Stroszek) harnesses the unique energies of unique people to get at something not found in most performances. In fact, the cast of Even Dwarfs Started Small is, as the title suggests, comprised entirely of dwarves. Even when casting Hollywood stars, he goes for the more interesting actors – Christian Bale (Rescue Dawn) and Nicolas Cage (Bad Lieutenant – Port of Call New Orleans) possess a rare willingness to go to extremes, which Herzog takes full advantage of. Bale, for instance, ate real maggots for the film.

Herzog is also a master of making his locations not just stages for his unorthodox casts, but characters in their own right. Large portions of Aguirre are set on a raft going down the river, flanked on both sides by thick Peruvian jungle. Few other films give such a sense of isolation, of being cut off from the world. As far as the audience is concerned, the jungle stretches on forever, and these men will never see “civilization” again. Even a film set in America, like the majority of Stroszek, is imbued with its own feeling of the States as a used, desolate shell of its own former glory, a land of sparse roads and plain buildings with fading colors. Because such films are shot on such real locations, the worlds feel authentic and absolute, never contrived.

Herzog seems obsessed with the idea of quests, whether it be Don Lope de Aguirre’s search of El Dorado, the mythical city of gold, or Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald’s journey to build an opera house in a similar Peruvian wilderness in Fitzcarraldo. Herzog’s process mirrors that of his characters, as he makes his films into quests of their own, going to unbelievable lengths to get his films made against all odds. He persevered during Kinski’s temper tantrums on the set of Aguirre (at one point Kinski fired his gun into a tent containing cast and crew members, knocking part of one man’s finger off).

During Fitzcarraldo, Herzog traded his shampoo for rice, and had his crew actually drag a steamship over a hill, not settling for any sort of model work or trick photography. Never content to rest on his laurels, Herzog pushes himself and those around him to incredible lengths. Whether throwing himself into a cactus field to make up for what he put his cast through in Dwarfs, or eating maggots along with Christian Bale for Rescue Dawn, he shows a tremendous and unparalleled dedication.

Toward the end of Stroszek, Herzog’s camera lingers on a captive, dancing chicken at a roadside attraction. “When I saw the dancing chicken,” he said in regards to the scene, “I knew I would create a grand metaphor. For what, I don’t know.” This idea essentially encapsulates his cinematic philosophy. He seems to work from the gut, rather than a classic analytical mind, capturing images and moments that captivate him in an intangible sense, rather than using them to inform some pre-planned symbolism. He often refers to a term he himself coined, the “ecstatic truth.” A memorable scene The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser features Kaspar, a man raised captive in a basement, now integrated into society, being presented with a theoretical problem of logic. He has to ask two guards one question to find out which is from the village of truth-tellers and which is from the village of liars. While the man presenting this riddle to Kaspar offers a complex deductive answer, Kaspar simply states he will ask the men “are you a tree frog?” He is told that this answer is unacceptable, but it’s hard not to agree with its validity. Here Herzog is telling us we do not always need to intellectualize everything – sometimes the answer can lie in simplicity.

Herzog has a rare ability to linger on striking images without it coming off as indulgent. Early on in Kaspar Hauser is an extended shot showing Kaspar, who has spent most of his life in a basement, sleeping on the grass, while his keeper stares out at the horizon and smoke wafts up from a dead fireplace. The length of this shot works because the viewer becomes aware of this moment’s subtle power for both characters, who are in unusual situations, but also for his or herself. Contemplation is universal, and the viewer is given a chance to contemplate along with Kaspar and his keeper. Herzog’s 1979 remake of F.W. Murnau’s silent horror classic Nosferatu features an unforgettable sequence of the character Jonathan Harker journeying through the mountains of Romania to get to the vampire’s castle in his 1979 Nosferatu, set to Wagner’s Das Rheingold. While the length of the scene does little to advance the plot, it overwhelms the viewer with the beauty of the landscape and the music.

Whereas many directors of art-house films, such as Ingmar Bergman or Michelangelo Antonioni, act as curators, guiding the audience from each painterly image from the next, Herzog is more like a trailblazer through the wilderness, sharing the joy and power of each discovery along with the audience. You can almost hear him saying “look at this” with each film. “Look what I have found.” He wants the audience to admire his discoveries, not himself, the art rather than the artist, and such humility distinguishes him. Any egoism would get in the way of the “ecstatic truth,” which is something primal and indefinable that speaks to some deeply buried yet very essential part of the human spirit.

All this speaks to a daring and fascinating artist who deals with the strangest of subjects with sublime naturalism (a trait which has clearly influenced filmmakers such as Harmony Korine, who cast Herzog in his films Julien Donkey-Boy and Mister Lonely). By doing so, he makes these things not alienating, but real and universal. Herzog has no time for the fakery that populates so many films (and even many very wonderful films). As legendary film critic Roger Ebert wrote, Herzog “has never created a single film that is compromised, shameful, made for pragmatic reasons or uninteresting. Even his failures are spectacular.” Looking at his incredible career, it’s hard to disagree. Even his films with more conventional stories, such as Rescue Dawn, still bare his distinct touch. Herzog’s restlessness and adventurous spirit show an incredible desire to transcend any kind of routine living. His life and films should inspire everyone, not just filmmakers, but all people to reach for something higher and purer. We need more people like Werner Herzog.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

A great piece about a great director! Very well written, nice job.

What a read, thank you!

I’ve always been put off by a distinct visual quality in Herzog’s early work. I can’t quite put my finger on it but I’d bet it has something to do with the cameras he was using at the time. Result being, I just wasn’t “transported” by either Fitzcarraldo or Aguirre where I can see I should have been. Nevertheless, I was absolutely bowled over and stunned by things he did later, like Grizzly Man, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, and The Bad Lieutenant. But maybe now I’ll revisit the early films — perhaps Kaspar Hauser since you get into it a little.

A Herzog film is an amazing experience. They transcend time, space and offer surreal depictions of the natural habitat.

Aguirre, Grizzly Man, and Bad Lieutenant POCNO are three of my favorite movies. Really need to see some more of his stuff. Excellent article (even if you didn’t mention his brilliant performance in Jack Reacher).

I haven’t seen it yet, but I really want to. The sound of him playing a villain in a Tom Cruise action film is delicious

It was at the beginning of the 80’s. I had already seen Herzog’s Nosferatu and was very impressed by it’s atmosphere and pace, the slow panoramic camera-movements, the interplay of sight and sound. Yet the opening scene of Aquirre caught me off guard. It was totally out of this world. Huge and steep mist-covered mountains and tiny people meandering downwards in long chains. This single scene put at once the rest of the film in perspective and I felt that everything that followed from that point on was predestined. Why am I telling you this? Because everyone has, I think, been touched very deeply by a movie or by some detail in a movie at least once in their lifetime. For me, this was the magical moment. This single scene.

Been waiting for my film taste to mature before diving into Herzog. You have inspired me to give it a go. Great article!

Don’t hesitate! Dive right in! You’re in for a treat

I was introduced by a friend to Werner’s work and I just cannot go past Grizzly Man and My Son My Son.. Just, enthralling films. Wonderful to see a tribute to his individuality 🙂

Fantastic, well-written article about one of our best and most eclectic filmmakers. I marvel at Herzog’s ability to move between documentary and narrative fiction film so effortlessly.

Every time I see a Herzog film, I always say to myself, “Dang, this guy keeps blowing my mind.” He’s amazing. Nosferatu is quite possible one of my favorite films. Much like you mentioned, the way he uses landscape in that film is spectacular. So many aspects of that movie make you ponder something new. One of my favorite sequences is when Jonathan is running through the many corridors of Dracula’s intricate castle, and then the camera takes us to an exterior long shot of the castle and it’s simply a bunch of ruins, nothing like we see on the inside. You begin to make a connection between the ruins of the castle and Jonathan’s mental state. Is there even a Dracula? A castle? Is this all a bunch of delusions in Jonathan’s head? Ah, I could go on forever. But yeah, Herzog = fantastic!

Great analysis of Herzog’s work.