Exploring The Hero’s Journey: A Writer’s Guide

Good, bad, or ugly, the Hero Story draws us time and time again to the bookstore, the TV, the theatre, the video game console – you name it – with the promise of experiencing “something”. Regardless of race, gender, age, socio-economic placement, not only do we continuously seek this something, we crave it, need it, like food, or a drug. This experience, this “something” we crave, takes us into a place that transcends beyond the obvious pleasure of mood-altering on good (or bad) story.

While most of us are familiar with the idea of the “hero” within a story, (perhaps in cape, spandex or armor, doing “heroic” deeds or action) most of us are not aware that this type of “hero” and story are superficial urges to express the deeper psychological meaning of the hero.

One of the many distinctions between the celebrity and the hero is that one lives only for self, the other acts to redeem society…Luke Skywalker was never more rational [or “heroic”] than when he found within himself the resources of character to meet his destiny (Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth, 1986).

Hero: Not Necessarily a Four Letter Word

The Hero has fueled stories for millennia. Everything from religious doctrine to fire side-tales: classic literature to pop fiction. In modern Western culture the Hero is present perhaps most prevalently in film. Hollywood, and Hollywood audiences, are in love with the Hero. The Hero’s Story, in all its guises, has generated billions of dollars of revenue with Hero based blockbuster franchises such as Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, Twilight, Harry Potter, and The Marvel Movies. For the modern popular writer, the Hero’s Story is a form(ula) tried and true. It has become the writer’s “magic bullet”. And it is this writer’s opinion that the mega-corporate industries are all too aware of our societies need for the Hero Story. Disney, Twentieth Century Fox, Time Warner: they bank on our need, our deprivation. We watch or read with bated breath, hoping that this time, this time, it will be a good story. Something with sustenance. Something that will take us to that place of transcended experience. It is unfortunate that most of the Hero Story based entertainment often fails to explore the full range and depth of The Hero’s Journey. As is more often the case then not, we writers tend to think more is more. The Hero based story, if utilized properly, can offer a complete and satisfying story in and of itself. Use of interjected material from the writer can, and has, ruined a great many of potentially satisfying stories. As writer, reader and audience, the more we know, the more we will be able to perceive, produce, and participate in making a fully realized Hero’s Journey as opposed to Hollywood Cliff Notes.

The Missing Myth

But first. What is this something that we crave from our modern films and theatre, our best selling book-shelves, our gaming grottos? What is it that we, as individuals and as a society, crave but are not getting? Why do stories like the Lord of the Rings Trilogy (both Tolkien’s epic and Jackson’s film homage) move us for decades? Why do we tend to think of, remember, and refer to the “characters” Luke, Han, Leah, Obi Wan, and Darth Vader as being “real” people? Tolkien and Lucas, as story tellers, were informed by myth proper. Our modern society lacks myth, and it is the myth that is missing in most of our stories. It is the myth that we crave. One of the functions of myths is to connect us with the internal: the spiritual or psychic processes contained within the human being. Myths allow us to experience that which cannot be named: the micro and macro cosmic mysteries of our existence. Myths that accurately and spontaneously express The Hero’s Journey are the vehicle to this experience.

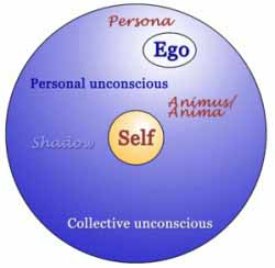

Psychologist Carl Jung theorized that within the human psyche exists something called the collective conscious and unconscious in which all humans store and access human specific content. This content is expressed in dreams, myths, fairy tales, stories, and folk tales through universal symbols (archetypes) found in all peoples in all cultures. And while the Hero archetype is but only one archetype out of many, it is so firmly fixed in human psychology that the motifs reappear again and again to express cultural and evolutionary changes. Mythologist and scholar Joseph Campbell is equated with bringing the concept of The Hero’s Journey to Western thought. In his 1949 publication, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell identifies the universal existence of something he terms the “monomyth”: a form of mythic story found over millennia within multiple cultures across the globe. The monomyth expresses the repeated paradigm of The Hero’s Journey.

In his 1986 PBS interview The Power of Myth, Bill Moyers posed this question to Mr. Campbell : “Why myths? Why should we care about myths? What do they have to do with my life?”

Campbell’s response:

One of our problems today is that we are not well acquainted with the literature of the spirit…we are interested in the news of the day…Greek, Latin, and biblical literature used to be part of everyone’s education. Now, when these are dropped, a whole tradition of Occidental mythological information is lost. It used to be that these stories were in the minds of people. When the story is in the mind, you see its relevance to something happening in your own life. It give you perspective on what’s happening to you. With the loss of that, we’ve really lost something because we don’t have a comparable literature to take its place. These bits of information from ancient times, which have to do with the themes that have supported human life, built civilizations, and informed religions over millennia, have to do with deep inner problems, inner mysteries, inner thresholds of passage, and if you don’t know what the guide-signs are along the way, you have to work it out yourself. But once this subject catches you, there is such a feeling, from one or another of these traditions, of information of a deep, rich, life-vivifying sort that you don’t want to give it up.

There and Back Again: A Hero’s Story

With a true understanding of The Hero’s Journey in myth, the writer can critically recognize, interpret, and assess how well it is employed in all story-based forms of writing.

All stories have a beginning, middle, and end. All stories with a protagonist express the protagonist’s journey: their beginning, middle, and end. If the protagonist in the story is a Hero archetype, the protagonist’s story will naturally express the universal structure of the The Hero’s Journey.

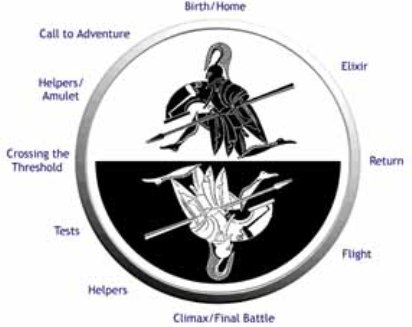

Campbell’s interpretation of the basic form of The Hero’s Journey includes three major phases: Separation, Initiation, and Return. Within each of these three major phases are various major substructures including: the call, refusal of the call, crossing the threshold, the belly of the whale, trials and initiation, preparing to enter the cave, finding the elixir, escaping the cave, the journey home, the final test, returning with the elixir and reintegration.

In the next few sections, we will break down The Hero’s Journey into its major parts and highlight some of the sub-structures within each. Because action films tend to follow The Hero’s Journey closely, we will look at the 1986 film Aliens, written by James Cameron. It is a prime example of how The Hero’s Journey (both an internal and external) can produce a potentially satisfying story within popular genre, but also how the writer’s interjection of material alters The Hero’s Journey as natural story structure and robs the audience of the total experience.

Separation: The Call

At the beginning of Aliens,The Hero (Ellen Ripley) is in a state of order. It ideally expresses both the external (physical) and internal (psychological) worlds of the Hero. Ellen Ripley’s external world is a fictive corporate space station, and Ripley’s internal world is a sparse and barren reflection of that space station. In the ordinary world of the Hero, there is some need or reason for change. This is referred to by Campbell as “the call”. In Ripley’s physical world, the call comes in the form of a request for help in returning to and determining what has befallen the colonists on the newly terraformed planet LB426: a planet she visited with her previous crew before the planet had been colonized. Ripley’s internal call comes in the form of her horrific nightmares: the result of a previous encounter with the planet LB426.

It is common in Hero stories for the Hero to resist the call. This is an accurate representation of the human psyche’s resistance to change. This resistance is embodied in Ripley’s refusal to go back to the planet until the psychological pain of her dreams reduces her to the barest dregs of herself. Finally she accepts the call, and her Hero’s Journey begins. This activates us as well and we are now on our own journey into the unknown. As soon as Ripley answers the call, the film cuts to her waking out of hyper-sleep with a group of Marines on a space ship that is orbiting the planet LB426. On both an internal and external level, Ripley has arrived at the place where her trauma exits. The place where she needs to accomplish her deed, find her jewel and make right what needs to be made right. Cameron has his Hero, literally, circling over her own psyche in the metaphor of the ship orbiting the planet. In terms of The Hero’s Journey, Ripley is about to plunge from the ordinary world into the extra-ordinary world of the adventure.

Initiation: Tests, Trials, Allies, and Enemies

The Hero has been transposed from the ordinary world into the extra-ordinary world: externally and internally. The Marines are metaphors for Ripley’s various personae: masks worn by the ego. Though allies, they are initially arrogant and brash, which presents the Marines as psychic muscling needed by the ego when it is confronted with a change or action.

Within the structure of The Hero’s Journey, the Marines and Ripley are about to “cross the threshold into the adventure proper”. They leave the safety of the space ship and descend to the surface of the planet. This crossing puts the Hero into what Campbell refers to as the “belly of the whale”. There is no going back. The Hero is now in the adventure, and she takes us with her. In this stage, the Hero will undergo a series of tests and trials, all in preparation to what Campbell refers to as gaining the “innermost cave”.

Once on the planet, the Marines are out of their element and reduced to dealing with the adventure on the terms of the extra-ordinary world. The colony is an abandoned and desolate war zone: raining, gray, a door banging fretfully in the wind. This setting is also representative of Ripley’s psyche: a psyche that has been ravaged by the Alien creatures that haunt her nightmares.

Ripley and the team of Marines set up a make-shift command center in the upper area of the main complex. Again, Cameron uses this physical setting as a direct metaphor for Ripley’s psyche. The complex is on the surface of the planet (Ripley’s conscious mind), and the rest of the structure is built in several levels that go down deep beneath it (Ripley’s unconscious mind). Ripley’s descent into her own psychological substructure is thus reflected in her physical descent into the colonists’ complex through the rest of the film’s story arc.

According to Campbell’s interpretation of the “classic”Hero’s Journey, the Hero-usually being male- will encounter the “Goddess” or feminine aspect (anima) of his psyche during the initiation phase. Ripley’s process as a female Hero involves two very distinct aspects: the discovery of the little girl, Newt, and her unrealized relationship with Marine Cpl Hicks. Newt is the only apparent survivor of the colony. She is dirty, traumatized and has survived by hiding from the Aliens that destroyed the colonists and taken over the complex. Newt is also metaphorical of Ripley’s inner self. Newt is innocent, pure and Ripley’s Heroic material is activated through her compassion and empathy with the girl. Compassion and empathy are one of the most universal (and quintessential) motifs of the Hero archetype. Cpl Hicks becomes the activated motif of Ripley’s animus archetype. He teaches her how to use the Marines’ specific weaponry, and Hicks and Ripley become co-leaders of the remaining Marines. This union, between male and female, parallels what Campbell calls “the holy union” in mythology. It is a uniting of male and female energy.

During the initiation phase of The Hero’s Journey, another vital sub-structure is dismemberment. The dismemberment can be physical, spiritual, metaphorical or psychological. Dismemberment purges away the ego and personae of the Hero so that the Hero can finally access and activate the inner attributes they need to accomplish the quest. This stripping away of ego is universal in Shamanic initiation stories. Shamans often report being dismembered and eaten by demons before being reborn into their initiated selves as Shaman. The Marines, as Ripley’s ego, are destroyed by the Alien species. For Ripley, the dismemberment of the Marines activates her own inner resources. She finds the strength to problem solve and discovers the courage to face the ultimate ordeal when she confronts “the shadow” in the “innermost cave.”

The complex and planet are about to experience an apocalyptic explosion, all but four characters remain and there is a plan in place for escape. Before that can occur, Ripley has to enter the “innermost cave”, confront her “shadow”, and win her “treasure” . Newt has been abducted by the Alien creatures and Ripley, as Hero, cannot leave without her.

The psychological entering of “innermost cave” for Ripley occurs before the physical. It occurs in the scene in the service elevator. Ripley is arming herself with the remaining reserve of weaponry as well as her hard won psychological attributes. Like the mythological Theseus, she descends deep under ground, enters the labyrinth of the Alien species’ hive and leaves chem lights along the way as she hones in on Newt’s beacon.

In the metaphorical “innermost cave” there always resides “the dragon” that guards “the treasure”. These metaphors represent the “shadow” of the deep unconscious. The “shadow” is the archetype that contains all of the conscious mind’s unwanted memories, thoughts, feelings, and urges: basically everything that the ego rejects. The “shadow” archetype also contains universal material. There is a natural predator in our psyches that hunts us in our dreams and in our complexes. When this predator (“the shadow”) takes over, it needs to be confronted and contained before order can be restored. By journeying into the psyche, the Hero can find the “sword of truth” to win the “treasure” needed to restore order. Cameron’s shadow in Aliens is the Queen Alien. Like the natural predator of the mind, she has infested the unconscious and conscious psyches of Ripley and abducted her “Self”. That self, “the treasure”, is the girl Newt.

Winning the treasure in mythic stories can be expressed through the physical (such as battle) or through wit (such as riddling). The shadow archetype can be contained and reintegrated into the psyche, but never destroyed. In many myths, the shadow (or shadow content) contains a tremendous amount of energy that can empower the Hero once properly channeled. Many video game Heroes exhibit this in the form of “shadow magic” that is both powerful and perilous. In choice based games, the Hero either uses it for good or for evil. In Aliens, Ripley deals with the shadow by engaging in a primal exchange with the Alien Queen. Through physical gesturing and bargaining, she wins Newt and escapes. But just as the shadow content seeks in some way to destroy or predate life, the Queen reneges and pursues Ripley and Newt.

Return: Flight to the Surface and Reintegration

In her Hero’s Journey, Ripley has undergone a series of tests and trials, both physical and psychological. She has confronted the shadow (both internal and external) and found her treasure or elixir of life. Now all that remains is her return to the surface and reintegration back into the ordinary world. Often, the Hero is obstructed, just as the Queen Alien pursues Ripley and Newt in their flight to the surface. Klaxons sound warning of the impending nuclear explosion, while fiery debris falls all around. There seems to be no escape. The Queen Alien has them trapped on a collapsing platform. Ripley holds Newt and tells her to hide her eyes. It seems like the pairs end until Bishop, the mission’s synthetic person, arrives and whisks them away to the mother ship as the planet explodes.

When Ripley escapes the planet with Newt, it is the natural end of the Hero’s journey. The natural integration comes when Newt asks Ripley if they can sleep and dream, and Ripley affirms to her that they can now sleep. Ripley has freed Newt and herself from nightmares. Ripley has completed the arc of the story and of the Hero’s Journey. However (as we see in all too many screenplays) it is not the end of the movie. While for the first three-fourths of the film, Aliens exhibits an unconscious depth of writing by Cameron, the last fourth is mostly untrue to the story and to Ripley as Hero. Before the ending scene in which Ripley and Newt reintegrate and discuss sleeping without nightmares, there is an epic battle scene between Ripley and the Queen Alien, who is now on their ship (The Queen apparently managed to climb aboard the drop ship – while it left the exploding planet – and survive a ride out of the planet’s atmosphere). Not only is this plot device ridiculous in its logic but it is simply there for gratuitous action. This, for us, creates a sudden aesthetic distance from the Hero’s Journey, and we are propelled out of the transcendent state of mythic experience into a place of objective observation. The scene serves to show us how a wild tangent inserted into The Hero’s Journey will appear to be just what it is – a stick on.

We were deeply invested in Ripley and the other characters in the story until this ending sequence. The true resolution of the story would involve our continued empathy with Ripley and Newt’s grief and pain. We, as audience, are bereft of this catharsis and cheated of its emotive purging. We do not get to experience the pain and dismemberment or the true joy of triumph and reintegration that the Hero naturally undergoes. Cameron would have done better to have left it alone and left us to suffer. It’s what we need.

When approaching the Hero in writing, it is important to remember that The Hero’s Journey is a form, not formula. It has been around for a very long time. While there is a specific structure (separation, initiation and return), we writers would do well to allow the content to evolve naturally out of the characters and out of our own psyches. By doing so, we will activate and fulfill the psychological needs of our audience. As exhibited in Aliens, impositions into the structure of The Hero’s Journey can leave an audience out in the cold.

Sources and Resources

Campbell, J. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. California: New World Library. 1949.

Campbell, J. The Power of Myth. New York: Anchor Books. 1988.

Vogler, C. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. California: Michale Wiese Productions. 1998.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Joslyn! This article is amazing. I am happy to see your success and glad to know that Goddard had something to do with that. I am currently enrolled in the MFAW program, first semester. Bravo Lady! I am so proud of your work. Hope to be in touch in the future. All best, Tamah

Hi Tamah,

So good to hear from you. Best of luck at Goddard!

Mostly character flaws make heroes fascinating to the reader.

Yes> The more flaws the better as they create conflict. And the more we know our character (hero) the more natural the flaws without having to depend on stick-ons.

This. When you create flawed characters, the audience immediately identifies with them (actually, the audience identifies with the need for the character to overcome their flaw).

What about characters like Aragorn from Tolkien’s LOTR (the book)? He is a typical romantic hero (old usage of the word “romantic”) who is superior in degree to other men and his environment (Picturing Tolkien 223). His role in the books is as a character that the reader admires and aspires to be like. The flawed hero popular today is considered “low mimetic mode” where he is not superior to either other men or his environment.

Kayla Wiggins argues in her article “The Art of the Story-Teller and the Person of the Hero” that character flaws in a hero actually cause us to feel superior to the hero and NOT to identify with him/her. She writes, “the effect is not to bring us closer to these characters but to shove us further away. We can’t know them with the fundamental recognition that is part of our primal consciousness, the part of ourselves that reaches out to myth…as essential truth” (quoted Picturing Tolkien 223).

Excellent article RJ. Myths, or for that matter storytelling in general, has always been such a large and fulfilling part of my life, and it’s truly sad to see that people tend to dismiss them on the grounds that they are too fanciful to be of any practical use in real life, thus missing out on the wisdom that such works can provide. As Campbell said, by disregarding a millennium’s worth of stories, people are abandoning one of the fundamental elements of their humanity. I recall when listening to the audio book version of “Team of Rivals” that one of the reasons that Abraham Lincoln was so popular with both his cabinet and great portions of the public was that he was fond of telling stories that could help them think their problems through. Such has been the enterprise of countless sages, and your piece is not only thoughtful but important in helping people realize the importance of storytelling. Great work!

Thanks for the thoughtful response. I think that we as story tellers crave to access myth through the creative process as much as the people listening. It is an exchange. For me it is the difference between producing “product” (no matter how well-crafted) and story (no matter how ill-crafted). I would take a good story any day over a brilliantly mechanized piece of prose.

That’s a great way of putting it; perhaps that’s why I tend to lean more towards movies/novels that tell a good story rather than try to arrive at some great existential truth. I figure that if a story is good enough, that truth will be revealed anyway, but if an author desperately tries to make that truth their goal, then it looks like they’re trying too hard. Thanks for the reply.

Thanks for all the work in writing this.

Thanks for reading!

Most good hero journeys are the ones with a good conflict. If there are enough obstacles (internal and external) that the hero faces, it will be something worth reading.

Yes, good conflict and high stakes. What will happen if the “hero” doesn’t get what they want? What will happen if they do?

Conflict/inner turmoil is also what propels the story forward. It makes the hero more developed, ’rounded’ and relatable. If there is nothing for the hero to conquer/overcome, the story/plot practically comes to a standstill.

Thank you so much for this great read. Are these “A Writer’s Guide” articles a part of a trilogy? Which area is up for exploration on the next one?

A trilogy, yes! I believe the next one will be on working with the Shadow archetype. Very complicated (and important), that stuff.

EXCELLENT execution of this article! Thanks so much! Maybe I *can* get through Act II after all!

Act II. The place we often come to think that we, and it (our writing), sucks! Write on.

when i was a little boy, i wrote my own comic book.. and without realising it, i apparently use most of those plot points in “hero journey” i think thats hilarious

As kids we are great story tellers. We have such a clear pathway to all the archetypal stuff in their psyches. Its when we get older that its harder to get past the crap in the conscious mind and just let the good stuff come up. Its all there, after all.

I have such killer plot-block at the moment.

An excellent breakdown of the Hero’s Journey…

I remember studying The Hero’s Journey when I was in college! Everything from Harry Potter, to Persepolis! It’s the classic way in which many stories are told!

When creating an unforgettable protagonist, you must know the entire iceberg. I struggle with this until I reach the end of my novel. Why does this happen to me, and to other (I think)?

It takes a long time to get to “know” your protagonist. I think the first draft is just that: getting to know your protagonist and their story. Then comes the re-writing: painful, but glorious as your character now takes over the show and calls the shots.

Best advice I can give is to try to sculpt a hero that breaks the mold!

This article was great! It’ll definitely help me with writing my own stories. Thanks!

This article is lovely, great analysis well written, thank you. I also teach writing and have talked a lot about the story arch of a main character following this same structure, i’m often teaching younger or less adanced learners so it’s nice to see a more detailed, psychological and philosphical take on it!

It is interesting, working with this stuff with kids. When you tell them a story, especially a myth or fairy tale, and them ask them to write down what they remember about the story, they have a natural sense of the structure. They don’t analyze it for craft elements. What they remember and relate back are the archetypes.

I struggle with making sure that my hero doesn’t get too many lucky breaks, that’s just boring. And don’t we want to punch those people in the throat that always get things handed to them? Don’t want that to happen in my book. Yikes!

Yes, put them up a tree, light he house on fire, and throw apples at them infused with few man-eating slugs.

Awesome read. I’m currently crafting a hero within my druid/steam-punk fantasy!

The contrast between the public perception of a hero and the hero’s own perceptions of her- or himself is an important thing to keep in mind. Often what is perceived as heroic behavior is actually quite self-serving.

My favorite example of this is the episode “Jaynestown” of the series Firefly. Jayne Cobb is an amoral thug, but something he does more or less by accident makes him a hero to an isolated community.

There does seem to be a trend in self-serving heroes these days. I think this type of hero accurately reflects and perpetuates the trend in American self-service-ism

I am a fan of the reluctant hero. It’s easy to “live” the story when the hero is just a regular person. The danger somehow seems more dangerous.

I often think of Thor. Not the Marvel Thor, but the Norse God. Thor was accessible to the “common Viking”: he loved to fight and drink. He was the “blue collar” Hero and so more identifiable to the “ordinary” man.

I’m a firm believer in the hero’s journey.

Thank you for posting it all for us would be writers. I link my readers to this magazine often.

I’m in a quest of refining character and this was useful, thanks.

I”m glad it helped. I often ask what my character’s personal journey is. Why are they doing what they are doing? Their physical journey should be a reflection of their psychological.

One thing that took me way longer than it should to figure out is that the `journey’ doesn’t have to involve travel. The story can take place in a small town or a single house and still follow the `hero’s journey’ structure.

Yes, the journey can take place in one room. Or just in the mind.

Story IS king.

Everyday heroes are a lot cooler than mythical ones.

Can you imagine your hero sitting besides the other great heroes of other tales? That’s one question that’s helped me a lot when constructing my hero and its journey.

Love this article and how it deals with what it means to be a hero in modern storytelling. Something I realized when reading this article is the best heroes to engage with are the ones with no prophecies given to them (i.e Lord of the Rings and Aliens.) When a characters like Ripley, or Frodo are not on a predestined path, the more relatable they are because they are aloud to make their own chooses.

I agree, but then I think that sometimes what happens with the more epic Hero stories is that the Hero, as a character, gets lost in all the trimming. Big or small, the Hero’s Journey is about the Hero, not the plot or setting.

Thanks for reading.

Love your article! I own Joseph Campbell’s book A Hero With a Thousand Faces and I wrote an article tying his book with the Doctor from Doctor Who, but it was not as detailed as yours. Wonderfully written and concise!

Good stuff! I am admittedly, poorly acquainted with Doctor Who, but what I have seen is fascinating and his character seems flexible in both the internal and external arcs of the Journey.

Thanks!

A goal of mine is to reflect on my character, maybe even identify with him by asking myself what I’d do in his stead. That way, I believe I can avoid boring my reader

I think my favourite hero is the anti-hero. The best-known example is probably Han Solo. The kind of hero who really doesn’t want to be a hero, is very sarcastic about it, but eventually gets caught doing something noble and then fervently denies it.

Fun topic!

Just give the hero a skill, power or ability that others lack. Luke Skywalker could sense the force. Sherlock Holmes had a keen mind and the powers of deductive reasoning…

Fantastic summaries, thank you very much.

My favorite books involve the hero’s journey.

This reminds me of my first antihero work, revolving around an unemployed family man who turns to sniping for money. He has both family values, and compassion, but compassion straining his conscience as he kills his client’s targets.

I love the anti-hero as well, my favorites are the two hitman, Ray and Ken in the film by Martin McDonagh, In Bruges. There was a great article written a while back here on The Artifice about the film and the Heroic arc of these two characters as being those of Knights. Worth a look if you are into the anti-hero archetype.

Thanks for reading and commenting.

Another winner, RJWolfe.

Good information.

The real deal is to blend the character’s archetype such that it doesn’t become a stereotype.

I studied archetypes in literature in school. The reason they are successful is most people know them intuitively from life experience. The author’s job is to communicate the clues and the reader will fill in the rest of the profile.

Yes, working with archetypes and avoiding making them stereotypical is a big challenge for the writer. I think what makes a hero (or any other character archetype) interesting and satisfying is the motif, the content, of the archetype. Though the hero archetype is familiar (it needs to be), the motif can potentially be quite varied and offer the writer (and reader) an endless and infinite expression of the individual.

Thanks for reading and commenting!

I think I’m going to write about my mixed passion fruit pie. YUM! Its been on my mind lately. And THEN, I am ready to break down a Hero’s Journey story.

thanks! really detailed

Thank you! This will be helpful in adding dimensions to my characters.

What majority of aspiring writers don’t get is to add a weakness to their character. Then attack your character at their weakest spot, and they will show things about themselves that they don’t want to reveal.

Yes, its called “being an asshole” to your character(s) Something us writers have a very hard to do when we love our characters. You have to do terrible things to them, and make them do terrible things as well. “Terrible”, of course, being relative.

Thanks for reading.

This just gave me seven new ideas at once for my story! THANKS SO MUCH!!!

Just so long as they aren’t all in the same story! That’s one of my problems, too many stories or “ideas” in one story.

Great! Thanks for reading and responding.

A very good deconstruction of what is portrayed in stories. Your pictures really add a nice touch!

I’ve realized how much pictures do tell a story. Its great fun to work with them.

Thanks!

Fantastic article! It’s so interesting how this story-telling form has been so effective over the millennia. Don’t fix it if it’s not broken! 🙂

Yes, it works. People complain that its all been done before, but its a paradox: if your story is a hero’s journey, it will basically tell itself, and it will be original, if you try to fit your story into the formula, it will be stereotypical. Basically, if you seek it, you wont find it, if you stop seeking it, you will find it. Very Zen, that.

Very good post. Try to know your hero. His dreams. His wants. His desires. All of it should be on page one. Or on page one in your mind. Who does he identify with?

We love to see characters acting bravely, so it is not only what the character is trying to accomplish that makes us cheer for him or her, but it’s the lengths he/she is willing to go to get it. Make sure the lengths are far. We want a journey. Good luck my dear writers.

Good stuff!!!

This is a great article, especially for those, like myself who like to write, but lack the guidance of how to create satisfying and complete story. I appreciate the conclusion on how you say that the hero’s journey is a form, rather than a formula.

Wonderful article! I’ve studied the hero’s journey briefly before but this makes it all much clearer. Well done!

Don’t forget that Newt also is a way for Ripley to redeem herself because Ripley’s daughter passed away while she was in hypersleep. Ripley was in hypersleep for 57 years and her daughter Amanda passed out during this time. Ripley made a promise to her daughter that she would be back for her 11th birthday, but instead never saw her again because of the events that unfolded with Alien. She saw Newt as a way to redeem herself, by protecting this young little girl.

Yes! Thank you for your comment. I was remiss in not including and clarifying that very specific plot point.

For me, the tie-in, according to the interpretation I offered in the article is this: Ripley’s loss of her daughter is connected to Ripey’s previous traumatic experience with LB4626. The trauma robbed her of both her daughter, Amanda, as well as her Self.

Finding and rescuing Newt fulfills Ripley’s physical and psychological needs and creates a comprehensive character arc.

Amanda is a symbol of the loss of Ripley’s Self, and Newt is a symbol of Ripley’s new Self achieved and healed through her Hero’s Journey.

Thank you, again for your well thought out and challenging comment.

Has anyone ever compared the heroes journey to the dramatica theory? I’ve found that using both methods simultaneously our at least parts of then have made my students better storytellers overall. Which I find internally important since games are just now really starting to push narrative experience.

I used to teach the hero’s journey exclusively but found it wasn’t really enough to flesh out the motivation’s of the characters. As you started about Aliens they always felt cold or formulaic no matter how imaginative the writer was.

This is one of my favorite topics to teach. It is nicely outlined here. Archetypes of any kind are, surprisingly, usually a new subject for college freshman.

Has anyone ever compared the heroes journey to the dramatica theory? I’ve found that using both methods simultaneously our at least parts of then have made my students better storytellers overall. Which I find internally important since games are just now really starting to push narrative experience.

This was an incredibly detailed, informative and thought provoking article. I have just begun my own journey to learn about this subject and I greatly appreciate what I got out of reading this article. Do you have any sources where I might find a reliable list of character archetypes that can be found universally (across cultures etc) that can be found in narratives and the human psyche? This topic greatly interests me. Thank you for enriching me with this article!

As a growing writer myself, I believe that characters should have more than one side to them. I always ask myself what motivates the character I’m writing about and the choice they made to get to where they are today.

Thank you for your work in this article. I really appreciated your application of Jung and Campbell to the Hero.

Great article! It’s always good to read about Jung and Campbell’s theory of hero.

Great write-up on Campbell’s theory, and I love that you used Ellen Ripley in here!

I am amazed at your thoroughness here. I especially appreciate the modern tie ins.

Well done! Such a great topic to cover and I love how you used Alien as your example of the hero journey.

star wars is amazing post

The best stories are made out of heroes and plots that totally destroy this mould. It has it’s places, but it is an old concept ripe for refinement and change.

This is a brilliant and thorough article, thanks so much for such attention. I think though that the take away that we should hold onto is not the sole mold of the hero’s journey, but also that the society we live in craves myth in the same way that our bodies crave water. We need myth in our lives. The hero’s journey provides a myth that helps the “I” or “Ego” aspect of the personality identify with the perils of the journey towards entering the personal spiritual identity that Jung called the Self. Though esoteric, I think seeing the Hero’s Journey as the entrance point for a much larger story is critical for us as a society.

A very helpful article, thanks. I tend to write from the seat of my pants, but have learned –the hard way– that following a loose outline and plot structure can save my editing budget down the line. I recently featured a post on my blog with 5 key plotting techniques, which you might find interesting. http://catehogan.com/how-to-write-a-novel-plot-structures/

Wonderful piece, and it’s very truthful about the Hero’s journey. The Hero in writing and film is what people wish to find in themselves, which is why it works so well.

very helpful.

Quite exquisite!

Great writing.