Do We Need the Author’s Approval in a Film Adaptation?

It seems gently ironic that John Huston received an Oscar nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay for his work on the 1946 film noir classic The Killers. The motion picture debuts of both Burt Lancaster and Ava Gardner, the film purports to be based on an Ernest Hemingway short story of the same title. In Hemingway’s story, penned in 1927, neither the killing nor the motives behind it are explained. The story ends with the doomed ‘Swede’ (Lancaster) waiting for the killers and the narrator, Nick Adams (Phil Brown), being admonished that it was “better not to think about it.”

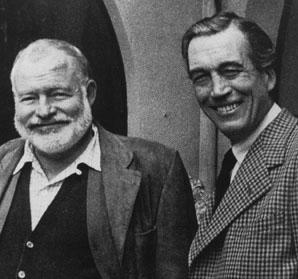

The script opens with a faithful recreation of the Hemingway story, but Huston then proceeds to “think about it” for another 90 minutes, inventing two new major characters along the way. Did Hemingway know when he signed over the film rights to Universal Pictures producer Mark Hellinger how drastically his story would be changed? In all likelihood the answer is “no.” But Hemingway’s involvement with the production did not end there. Indeed, he would go on to offer John Huston advice on his screenplay. The two men were contemporaries and, having common interests, they became good friends — both were avid hunters and both were taken with Ava Gardner. A strong argument could be made, however, that Hemingway’s stamp of approval on the production was ultimately irrelevant to the film’s artistic success.

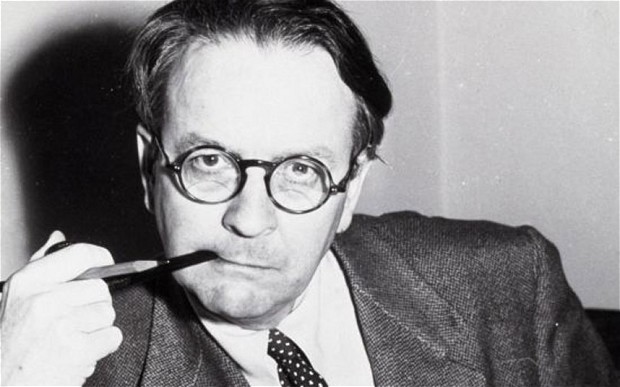

Let us now move to another studio, another crime story, another source author and another screenwriter — respectively: Paramount Pictures, Double Indemnity, James M. Cain and Raymond Chandler. Cain, a newspaperman-turned-screenwriter, was inspired to write this novella after covering a murder trial for The New York World in 1927. In the actual case, Ruth Snyder and her lover plotted to kill her husband Albert after having him take out an insurance policy with a double indemnity clause, which is to say that the payment on the life insurance policy would be doubled if death appeared to be accidental. That the woman’s lover should be employed as an insurance agent was a contrivance of Cain’s imagining. Mrs. Snyder and her lover were apprehended shortly after the murder and Mrs. Snyder’s later execution at Sing Sing was captured in a well-known photograph. So influential were the details of the trial on Cain that he wrote the tale twice — the same basic story and themes are revisited in The Postman Always Rings Twice.

By most accounts, director and co-writer Billy Wilder’s first choice to write the screenplay was Cain himself, but he was under contract to another studio at the time and consequently unavailable. Raymond Chandler was available, though, and he was a Paramount contract writer at that time. By the end of their tumultuous collaboration, the resulting screenplay was more “Wilder and Chandler” than it was “Cain.” Even the lead characters’ names had been changed in their adaptation.

For what it is worth, Cain was pleased with the result when he saw the film as a member of the general public. He said that it was “the only picture made from [his] books that had things in it [he] wished [he] had thought of.” Cain also conceded that the Wilder and Chandler ending was much stronger than his own, and even acknowledged the wisdom of increasing the prominence of the insurance investigator (played by Edward G. Robinson).

Perhaps all it takes is a great screenwriter to properly adapt someone else’s work. In that case, one could justifiably call John Huston the master adapter, so to speak. His astonishing directorial debut came in 1941 with The Maltese Falcon, adapted from the Dashiell Hammett novel. By the time Huston got around to it, Warner Bros. — which owned the property — had filmed it twice prior, in 1931 under the original title and in 1936 as Satan Met a Lady, the latter of which starred Bette Davis of all people. The ’31 version is notable as detective Sam Spade’s most uncensored and only pre-code movie appearance. Yet, it was screenwriter Huston who, ten years later, adapted the novel most faithfully, taking Hammett’s dialogue and oftentimes incorporating it verbatim into his script.

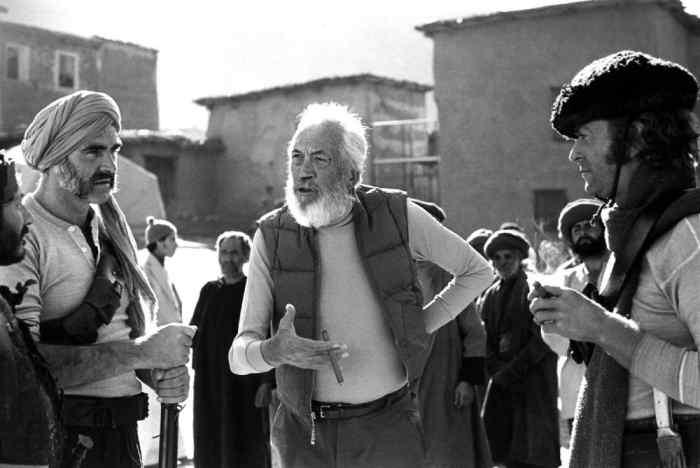

It was an innovative idea in an era when literal adaptations — such as Erich von Stroheim’s mammoth production of Greed (1924) — had given way to looser translations of literature that interpolated events while eliminating and combining characters — case in point Wuthering Heights (1939), which only covers material from the first seventeen of the thirty-four chapters in Emily Brontë’s classic novel. Remaining faithful to the source author’s spirit was a principle which informed much of Huston’s future literary adaptations, ranging from his treatment of Melville’s Moby Dick (1956) to Kipling’s The Man Who Would Be King (1975). Late in his life, John Huston even tried his hand at adapting to film the rather unwieldy prose of James Joyce with The Dead (1987).

Now, it is one thing for a screenwriter to adapt an author’s work during his or her lifetime. But it is very different to do so once that author has passed away. The great promoter of British imperialism, Rudyard Kipling died in 1936. The following year director John Ford, under contract to 20th Century Fox, helmed the screen version of Wee Willie Winkie, ostensibly based on Kipling’s short story. In 1939, director George Stevens, over at RKO, turned his attention to the 1888 Kipling poem Gunga Din. Both films paint terribly flattering, if wholly inaccurate, portrayals of British India and one therefore has to assume these adaptations would have met with Kipling’s approval.

In the decades that followed, though, film adaptations of Kipling’s work took on a slightly more subversive tone. It is difficult to say what Kipling would have thought of Disney’s animated classic The Jungle Book (1967), but it is logical to assume that his Baloo would not have sounded like Phil Harris, his vocal mannerisms far removed from the erudite educator portrayed by Kipling’s character. In addition, it is easy to imagine Kipling’s displeasure upon hearing the great Sean Connery’s line in Huston’s Man Who Would Be King; introducing natives to Western methods of warfare he says “we’ll teach you how to slaughter your enemies like civilized men.”

Rudyard Kipling never went to Hollywood, though he did spend time in Connecticut. It is surprising how many great American and British authors did spend some time toiling in the motion picture business — among them are Theodore Dreiser, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, Raymond Chandler, James Hilton, Graham Greene, John Steinbeck, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, Harold Pinter and Arthur Miller. The list just goes on and on and on. But the experiences of a few writers are worth exploring further.

First and foremost, it is important to return to Raymond Chandler. What was it about the ‘City of Angels’. as he knew it, which was attractive to Chandler? It could be argued that Chandler neither loved nor hated Los Angeles and its inhabitants. Indeed, his writing captures the city and its citizens with an emotional distance that a native Los Angeleno would be hard-pressed to match. But what drew him to sunny Southern California in the first place? He could have written about Chicago, where he was born in 1888. He could have written about London, where he was educated. He might have written about Paris, where he lived after serving in the Canadian Army during the First World War. Still further, he might have turned his literary ambitions toward Vancouver or San Francisco, where he was employed as a banker. He first arrived in L.A. in 1912, living in an apartment on Bunker Hill, before that part of the city had begun to decay to the state in which it appeared when Chandler later wrote about it. He would return in 1919 for good, living at various times in Hollywood, Palm Springs and La Jolla.

The Big Sleep was Raymond Chandler’s first novel and it was published in 1939, when he was 51. The movies soon came calling and in the mid-40s Chandler was working, however briefly, at Paramount Studios. His first project there was the screenplay for Double Indemnity (1944) and his experience collaborating with director Billy Wilder was sufficiently stressful to drive him back to alcohol after some years of sobriety. It is said that Chandler’s drinking problem inspired Wilder’s subsequent film, the Oscar-winning Lost Weekend (1945). No wonder, then, that in his lifetime Chandler would produce only three more screenplays — including The Blue Dahlia (1946) and Strangers on a Train (1951), the latter of which was a collaboration with Alfred Hitchcock. Seven decades on from the original publication Chandler’s novels, the Los Angeles he knew has largely disappeared under a blanket of smog and the congestion of its many freeways.

Of all the dozen or so film versions of Chandler’s novels, Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye (1973) is certainly the most controversial. It is viewed by Chandler purists as a travesty and even its defenders must admit that Altman seems to intentionally stray from Chandler’s ambitions for the novel. For what it is worth, the screenplay was written by Leigh Brackett, who had previously collaborated on the screenplay for Howard Hawks’ The Big Sleep, often considered the best screen adaptation of a Chandler novel.

Altman himself has commented on his departure from the source material, saying: “I see Marlowe the way Chandler saw him, a loser. But a real loser, not the false winner that Chandler made out of him. A loser all the way.” In that sense, as one critic has argued, Altman’s film essentially retains the spirit of the Chandler novel, but plays with the form. This, of course, is exactly what Chandler and Billy Wilder did with Double Indemnity — they retained the spirit of James M. Cain’s novella, but were uninterested in remaining faithful to all the particulars of the plot. Likewise, Chandler did not expect other screenwriters to stick closely to the source material when they were adapting his work. In all likelihood, given the mood of Los Angeles in the ’70s, Altman’s claim that Raymond Chandler would have appreciated the film for what it is was a valid one. That Chandler’s novels can be successfully translated beyond the borders of time affirms the claim of former UCLA librarian Lawrence Clark Powell — Raymond Chandler was the laureate of Los Angeles.

Two of the more popular films to come out of Hollywood in the early ’60s were the wildly divergent Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) and To Kill a Mockingbird (1962). Both were adapted from novels, the former by Truman Capote and the latter by Harper Lee. At one time, Capote and Lee were good friends. By all accounts, Capote inspired the character of Dill in Lee’s novel; it seems quite reasonable that this peculiar secondary character could grow up to be Truman Capote.

An attention whore with an eye for the perverse, Capote wrote a novella in 1958 called Breakfast at Tiffany’s and it was much more downbeat and less romantic than the later Blake Edwards film. The film’s shift in tone to the more romantic works largely to its advantage, providing Audrey Hepburn with one of her most iconic roles and giving the world one of the all-time great soundtracks from Henry Mancini, including Moon River. In fact, the only aspect of the film that doesn’t hold up today is Mickey Rooney’s insensitive portrayal of Mr. Yunioshi, a buck-tooth Oriental with Coke bottle glasses — it’s an excruciating stereotype. While Edwards no doubt takes significant liberties with the source, and Hepburn was hardly Capote’s ideal Holly Golightly, audiences were nonetheless captivated by the film’s depiction of this free spirit. It may be that the popular opinion is the only one that matters, the author’s feelings be damned.

The film version of Harper Lee’s Pulitzer-prize-winning, semi-autobiographical novel, To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) was one of those rare screen adaptations that pleased fans of the book and its author as well. After seeing the film, Lee commented, “I can only say that I am a happy author. They have made my story into a beautiful and moving motion picture. I am very proud and grateful.” Set in Lee’s hometown, Monroeville, Alabama, To Kill a Mockingbird vividly captures a specific time and place when racial unrest was at its peak in the South. Yet despite its controversial nature (a black man is accused of raping a white woman), the real focus of the story is the relationship between Scout, a tomboyish six-year-old, her older brother, Jem, and their attorney father.

As with the novel part of the film’s huge appeal is seeing the dramatic events unfold through the innocent eyes of childhood. Gregory Peck was so perfect in the role of Atticus Finch that Harper Lee turned down offers in later years for television and stage versions of To Kill a Mockingbird, stating “[the film of Mockingbird] was a work of art and there isn’t anyone else who could play the part.” Once again, it is noteworthy that the screenplay for the film was from Horton Foote. At the time, Harper Lee was busy working on another novel — not Go Set a Watchman — which has yet to materialize. Therefore, Lee’s comments after the production of To Kill a Mockingbird have no bearing on the film’s artistic success.

It may be beneficial when a screen adaptation is written by a person who is interested in the same things that interest the author of the source material. Therein lies the success of Robert Altman’s Short Cuts (1993) from the work of Raymond Carver, for example, or the Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men (2007) from the Cormac McCarthy novel. Certainly Horton Foote, in adapting Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, displays a profound understanding of prejudice, discrimination and the loss of innocence to an extent which rivals the novel. That is perhaps the only requirement of an adaptation, to approach its subject matter with the same level of seriousness and sensitivity as the source material. If Harper Lee had hated the film of To Kill a Mockingbird, that would hardly diminish its greatness.

Works Cited

Brackett, Leigh. “From The Big Sleep to The Long Goodbye and More or Less How We Got There.” Take One. 23 January 1974, Volume 28 Issue 3.

McGilligan, Patrick. (1986). Backstory: Interviews with Screenwriters of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Los Angeles: University of California Press. Page 125. ISBN 978-0-520-05689-3.

Phillips, Gene D. (2000). Creatures of Darkness: Raymond Chandler, Detective Fiction, and Film Noir. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press. Page 170. ISBN 978-0-8131-2174-1.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I just wanted to say thank you for writing one of my topics, and I’m glad that it was put in capable hands. I really loved reading about all these different film and the books they were based on.

What a great and in depth article. Thank you. I am often frustrated when people say “It wasn’t as good as the books.” I find film and literature to be different forms of art and almost impossible to compare. When discussing dialogue, character development, plot or whatever else, people often forget that movies are visual and do not have the luxury of time. Your article though, succeeds in discussing the difficult topic of film adaptations, specifically in one very important subject – the intent of the artist – something that is often forgotten.

This really is a very well written article and it covers a wide scope. I know that there is more out there but you have given a great cross section and handled it very well. It is also nice to complement a fellow York student!

This is a great topic. I just took an entire class on adapting literature into films. There are some that are done very strictly and wonderfully, and some done well but differ drastically from the script. Sometimes the title is just marketing if the movie is completely different and sometimes it’s impossible to put into film what was in writing. Whatever the case may be, this is a tricky process for all parties involved. Great article!

Ultimately you have to accept that the movie and the book are two totally different things. Lots of great movies have been made out of crummy novels, like Jaws and The Godfather. It’s easier to insert memorable lines and nuanced character bits into those kinds of stories than it is to take complex or deep books and make good films out of them. The most you can hope for is that the filmmakers really love something about the author’s voice and can translate that successfully into a movie. Peter Jackson’s LotR movies are a perfect example of that. They take tremendous liberties with the source material, but because the characters still act and sound like their literary versions — for the most part — most fans didn’t mind.

Suddenly, the Hobbit.

Peter Jackson now can’t seem to go a single scene without adding a ridiculous and barely enjoyable fight.

It’s funny that Peter Jackson has joked that Ian McKellen walked around with a copy of the Hobbit arguing in favor of original content.

Thank you for the above comment.

Obviously, filmmakers cannot please everyone. Ultimately here I think it comes down to a concession about interpretation: no matter how interesting or informative an the artist’s intent may be, it is by no means sacred. Power, if we believe Barthes, lies with the reader/viewer. Whether an author intended something to be a certain way does not matter because viewers will interpret that something in a multitude of unforeseeable ways. It’s the open-ended textuality of a work of art that’s exciting.

Authors usually have a set idea of what their story is about, and ANY deviation from that may be hard to fathom.

For instance: Alan Moore. He refuses to watch The Watchmen, trashes it constantly, and believes many of his stories CANNOT be re-imagined. However, I think it turned out okay.

I think the ending of the movie made better sense. The alien scenario was more of a what if, where Dr. Manhattan was known world wide, used his powers in Vietnam to stop that war. Maybe Alan Moore was angry cause he realized it too.

Stephen King has said he likes Frank Darabont’s ending of The Mist more than the books. So do I.

In the case of Stephen King though, he generally doesn’t like the film adaptations of his work, The Shining’s in particular for the way it treated the main character Jack Torrance. While Kubrick’s film adaptation emphasized primarily Torrance’s darker qualities, for King, Torrance was meant to represent King’s own struggle with alcohol addiction. Because The Shining was ultimately a personal work to King, perhaps there should’ve been at least some consideration given to the author’s original intent as a general principle, regardless of how successful The Shining was as a film.

Moore would probably hate the movie, but most of his objections stem from the fact that DC screwed him and Gibbons out of the Watchmen rights back in the ’80s.

It’s become very fashionable to hate on Moore as an anarchist wizard killjoy who hates his fans and the works that made him famous, but his grievances against the comics industry are entirely legitimate.

Really? I thought it was cold and awful and didn’t have a point. And yet I adored the book.

Heavy involvement from the original author can be hugely beneficial when making an adaptation and but it can also be extremely detrimental if the author is too protective of their own work, unwilling to comprise or blind to what the visual medium needs.

Authors probably should be more involved with adaptations but ultimately making movies is very different job from writing novels. Just because you can write a book doesn’t mean you can write a screenplay.

^This. The reason things are the way they are is because it’s convenient for most authors. They’re smart enough to know that movies are a different beast, they get good money for it and by not being directly involved they won’t get blamed if the movie sucks.

Stephen King sells his rights for a buck I heard.

I’m still waiting for the original running man to come out, but in the current climate that will NEVER happen.

Okay, I haven’t read Gone Girl, but from what I have learned from a couple of articles, there are some pretty huge differences between the film and the book, not the least of which is making Affleck’s character much more sympathetic. I wish I knew why that happened… Was it Flynn’s decision? Or Fincher? Or is it all in Affleck’s performance?

There are great screenwriters who are lousy novelists, there are great novelists who are lousy screenwriters, and there are people who manage to be great at both. There’s no hard and fast rule.

Well put!

I think that the author should always have some kind of involvement. Not necessarily creative control, but at least a right to provide input. I feel like they should at least be allowed to say what they would like to keep, or what kind o message they’d like to get across, even if it doesn’t mean that the script will respect it.

Fight club, is a great example of a poor book being made into a fantastic film.

I just didn’t get the book. I love reading, have a daily 2 hour commute so will read almost a book a week. Often I see a writer where a film would be perfect (Michael Marshall smiths Straw Men prime example)

Maybe I should give fight club another chance, I have heard great things from a few people now

I love the film but fight club is far from a poor book. I found it pretty funny.

Films like Holes come to mind when thinking of great adaptations but of course with a lot of source material, consent can’t be given because they are gone. Their is something to say about transitioning mediums in that it isn’t always wise to have an author direct or even envolve themselves too much in the filming process… Frank Miller anyone?

Another aspect is the audience. The reader of the literature has their own mental images and movie playing in their head as they read the authors work. While no two humans think exactly alike it cannot be expected the author and the film maker will see things in the same way. When the film is made the reader and perhaps author may find the film disappointing because it is not as how the reader or author envisioned the work.

True, but movies frequently make drastic changes to the plot that negatively affect its message(s). Forget nitpicking over casting or sets; if all that directors did in regards to the plot was edit to meet time constraints, then I would have much less to be upset about. As it is, too often they ADD at the expense of near plot-essential details or meaningful scenes and statements. I can usually get over the disparity between my view of a character or location and the actor/actress/set chosen, so long as they keep what is most important. Similarly, there have been films (i.e. the more recent Chronicles of Narnia) whose casting, props, sets, and the like all were nearly spot-on but which destroyed the story itself.

I remember King or Harlan Ellison quoting someone — maybe John Updike? — talking about selling options on novels. It went something to the effect of, “They give you a bunch of money for the movie rights, and then you pray it never gets made.”

Depends on the author and filmmaker involved. Different mediums require different perspective. This explains why The Shining film works despite King’s objections.

Trainspotting is one of those films that was a great book, and a great film, and different from each other.

Sometimes the images are so vivid in the reader’s mind that it’s hard to translate it onto the screen. It’s just as how we struggle to find the words to describe something we feel strongly about.

Perhaps this is why we feel disappointed when the book is better than the film, but it’s hard to get everyone’s vision in one movie. After all, movies are the director’s vision, so everyone is following their interpretation of the book.

lets just be forever grateful to JK Rowling for preventing a Haley Joel Osmond Harry Potter

Great article! Adapting books to film is so complicated and interesting, I love learning about it.

In the end you have to look at the film as inspired by the novel. There are films that I hate, but love the novel that the film was based on. Vice versa, I really enjoyed Gone Girl as a film but disliked the novel.

It’s always great when you can enjoy both the film adaptation and the novel.

You don’t need author’s approval once the rights are given away, but it would be nice. I feel like it would bring great gratification to the screenwriter/director to know that the original author was fond of the film adaptation. I personally like when original authors are involved in the film, whether as a writer or producer, because, ultimately, this was a world that they created and they should know it better than anyone else. Certain elements may not have made it in the novel, but could work in a film adaptation, and the original author could provide insight into those elements.

Some authors just aren’t suited for the film industry though, so it is a tricky balance.

I almost completely agree with this; if a director truly focuses on the spirit of a novel, then the movie will usually capture what is most important: the messages and feelings. There are also times when a book lacks a truly meaningful central message (i.e. Mary Poppins) and a film provides it with one. Also, I know that it is very difficult to convert a novel into a film. HOWEVER most deviations made from an author’s work done nowadays seem to be done because the director thinks that it will boost its box office sales (What, did the original story not sell well?), or because the director has a set style that they refuse to alter or let go of, even sometimes at the price of losing obscene portions of the story’s meaning (i.e. Walt Disney). In my opinion, too many people use the difficulty of adaptation as an excuse to make major changes that, if anything, take more screen time and require more resources. There are usually ulterior, monetary motives, and the most meaningful scenes in books are often the first to be cut or altered.

P.S. Do you know that some directors seeking rights to the Harry Potter series wanted to make Harry an American to boost sales in America? And I thought that those movies were bad enough! Though I do give Chris Columbus credit for doing so well with the first two. One can tell that he was really trying to convey the spirit of the books.

Really interesting take. I tend to prefer books over film adaptations simply because I visualize the stories so vividly, and then the film may not match my visualization, making me feel as though there’s misinterpretation when that may not be the case.

I think the involvement of the author can be very beneficial, and often helpful to creating a good adaptation. However, I believe the most important thing is creating something worthwhile–regardless of format. Breakfast at Tiffany’s is a good example of an adaptation that, like you said, is not faithful to the book, but still (despite its flaws) seems to create an enjoyable film that resonates with people.

Collaboration is key I think when it comes to film adaptations of anything really. Whether the director is making a movie about a certain point in history or a book, coming together with someone who has a better understanding of the text you are trying to replicate will bring both the director and the audience something to look forward to. Its good to keep in mind who is going to watch the movie you have just produced. People who were adamantly into the Harry Potter franchise had certain expectations for the characters and the story, so you need to watch out. However, if you solely focus on trying to please the viewer, chances are somewhere along the way you will trip. I feel like it really comes down to a balance of both collaboration with the expert of the text and the creativity of the director.

Authors approval or not, a film should just be good. There are times when the author and director can collaborate and create something original from the source material, such as 2006 film Little Children, but there are also times when the writer has to change the source material or else it would either be a period piece or something that just wouldn’t work. The example given in the article was The Long Goodbye but you have to remember that when those books were written. It was a completely different time and frame of mind than when the film was made in 1973. Altman knew this and had the character of Marlowe play out as though he was still in post WW2 Los Angeles even though it was set in the 1970’s. That is probably what makes The Long Goodbye the most interesting to watch out of all the adaptations listed.

I often wonder why we feel the need to ask this question. I suppose it is unfortunate that many authors are unable to exercise such a level of control over their properties that the results are not up to what they would desire for a film adaptation. Many authors don’t necessarily end up controlling the rights to their works, which is another factor that could result in frustration. Otherwise, unless one is willing to do the job themselves from script through production and editing and/or find someone willing to give them a controlling interest in the film, I would think that in some ways the author should be more upset with themselves for selling the work under anything but the most controlling conditions.

When Kubrick wanted to make Lolita, Nabokov resisted until he was offered a good chunk of money. Then he was able to get more money for writing a screenplay of Lolita. They did not use much, if anything, of his screenplay. Ultimately he was happy with the resulting film, noting very rightly that it was not “his” film, but that they did well considering the subject matter and restrictions placed upon them.

Was it his ideal adaptation? No. Was it his adaptation? No. Was it his book, Lolita? No. Was he happy with the money he made? Yes. This might raise questions of Nabokov’s artistic integrity, but if you are familiar with Nabokov you will note that his integrity (as far as one can tell based on his multiple masks in fiction and life) is fairly unimpeachable. My feeling, as a scholar of Nabokov, is that he saw a difference between the two objects. One was his and one was someone else’s. The similarities lay primarily in the title.

I think getting permission from the author should be a thing to do. It is their work and that is what the film is based on so it is a given to get permission.

This is really interesting; while I was aware of some of your book-to-movie examples, a few were brand new to me.

I’m glad you brought up Harper Lee’s commentary on her friend Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch. They forged quite a friendship when Lee was on set for TKAM, the film; so much that Peck is actually clutching the pocket watch of Harper Lee’s deceased father when he accepts his Academy Award for the role. Truly, as you point out and as articulated by Lee… it’s not often we (as readers and viewers of films) get to see an actor so perfectly portray a beloved, complicated character in literature as we did with Peck as Finch.

You also bring up Mickey Rooney’s incredibly racist portrayal of Holly’s landlord in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Thank you! I’d love to see more scholarship and discussion about why this character was included and portrayed in such a manner in the film.

Great read. Thanks!