Comics Without Superheroes: The Literary Value of Graphic Novels

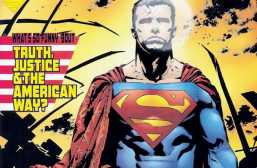

When people think about comics, chances are that they envision colorful superheroes flying over the city and through space fighting aliens, gods, and other super baddies. And who can blame them? Superhero movies currently dominate the box office, television shows based on or around comics and comics culture are emerging as ratings powerhouses, and the San Diego Comic Con has become a huge pop culture phenomenon encompassing more than just comics. But comics are more than superheroes and aliens. Comics have become a literary medium, which, as Hilary Chute explains, allows them to be “what novels used to be—an accessible, vernacular form with mass appeal”. The graphic novel has even entered the halls of academia, becoming source material for literary studies. The combination of images and narrative are a highly accessible and engaging form of storytelling. This allows for comics to tell more than just fantastical stories about heroes, but breach political subjects, tell a personal narrative, or just be a solid piece of literature.

Socio-political Issues in Visual Narrative

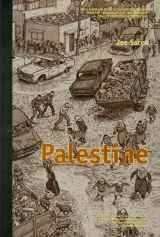

In 1993, writer/illustrator Joe Sacco began publishing his 9-issue comics series Palestine, later reprinted in trade paperback in 2001. In this work, Sacco explores the tensions between the Israelis and Palestinians—but he does so by focusing on the Palestinian perspective, specifically those living in the Occupied Territories. Through the use of comic form, Sacco presents a journalistic exploration that reveals information not readily distributed by mainstream American media.

In 1993, writer/illustrator Joe Sacco began publishing his 9-issue comics series Palestine, later reprinted in trade paperback in 2001. In this work, Sacco explores the tensions between the Israelis and Palestinians—but he does so by focusing on the Palestinian perspective, specifically those living in the Occupied Territories. Through the use of comic form, Sacco presents a journalistic exploration that reveals information not readily distributed by mainstream American media.

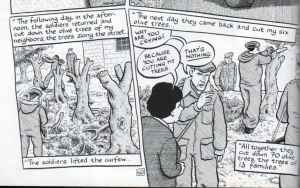

The revelations come early on when Sacco depicts his interview of a Palestinian man he meets in Nablus. This man points out to Sacco several specific individuals that he knows who have lost fathers and sons to imprisonment or death resulting from conflicts between the Israelis and Palestinians, though context for these conflicts is not given. However, other interviews with Palestinian people reveal that their homes are destroyed—literally bulldozed to the ground by the Israeli military, olive groves used for agricultural purposes are destroyed for little or no reason leaving people with no means to support themselves or their families, and the people affected feel that there is nothing that can be done; they can’t stop the Israelis and the Palestinian government gives them little or no support and protection.

What is most effective about Palestine is the approach that Sacco takes in presenting his story. Blame is not placed on either side; fingers are not pointed. Instead Sacco gives faces and voices to those affected by the conflict between Israel and Palestine. He humanizes suffering and reveals the true effects of the conflict, the human effects. Also, the illustrative representations of the people in the story add to the weight the story carries. The cartoon-like representations help the reader to sympathize with the victims in the story. The simple caricatures don’t perfectly represent the real people that they are based on, and instead can just as easily represent someone’s neighbor down the street, a co-worker, or a classmate.

Creative Biographical Introspection

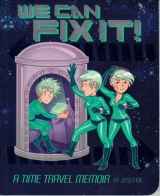

Jess Fink also puts a face to suffering in her bio-comic We Can Fix It. In her work, Fink explores her past by going back in time and attempting to help younger versions of herself make better decisions. The premise is a bit ridiculous (as is the character of Jess, clad in a shiny, curve hugging body suit hopping through time in a machine that looks like something from early cinematic science-fiction) but effective.

Jess Fink also puts a face to suffering in her bio-comic We Can Fix It. In her work, Fink explores her past by going back in time and attempting to help younger versions of herself make better decisions. The premise is a bit ridiculous (as is the character of Jess, clad in a shiny, curve hugging body suit hopping through time in a machine that looks like something from early cinematic science-fiction) but effective.

The adventure begins harmlessly enough, with Jess initially attempting to teach past versions of herself how to strengthen her sexual performances in her teen years. The stylized cartoon illustrations and blunt humor make the subject matter more entertaining than off-putting for the reader, such as when Jess becomes intimate with her past self.

The humor also blunts for the reader the sharp edge of personal trauma that follows as Jess’s adventure continues. Jess revisits points in her past where she was teased by classmates and made to feel like an outsider after changing schools in her early teens, to which many can no doubt relate. The major point of trauma in Jess’s past is revealed in the instance where her father kidnaps her from school. As Jess attempts to help her past selves to make better choices, or at least different choices to repair or avoid shame and embarrassment, she realizes that even after going back through time, having gone through these experiences again, she still does not know what she is doing and is unable to effect the changes that she wishes to.

The humor also blunts for the reader the sharp edge of personal trauma that follows as Jess’s adventure continues. Jess revisits points in her past where she was teased by classmates and made to feel like an outsider after changing schools in her early teens, to which many can no doubt relate. The major point of trauma in Jess’s past is revealed in the instance where her father kidnaps her from school. As Jess attempts to help her past selves to make better choices, or at least different choices to repair or avoid shame and embarrassment, she realizes that even after going back through time, having gone through these experiences again, she still does not know what she is doing and is unable to effect the changes that she wishes to.

The turning point for Jess comes when she gets advice from her own future self. Jess’s future self points out that she can’t repair the past, not matter how much she wants to, and that it’s not only the bad times but the good times as well that make people who they are; that make Jess who she is. Jess takes this to heart and travels back to relive some of her best memories. This brings closure to Jess as well as a sense of satisfaction, because even though she couldn’t fix her past mistakes she realized that her mistakes didn’t need to be fixed.

Comics as Literature

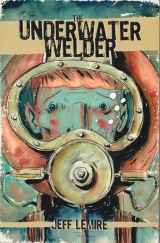

Closure is also something that the main character in Jeff Lemire’s The Underwater Welder desperately needs. This dark, depressing, and superbly presented story follows Jack Joseph, a welder for an oilrig off the coast of a sleepy New England town, in the days leading up to the birth of his son and the anniversary of his father’s death. The confluence of these two events thrusts a tremendous amount of emotional stress upon Jack, causing him to have a psychological breakdown that forces him to confront suppressed memories from his childhood. What follows nearly costs Jack his life, while at the same time giving him a chance to create a happy life for himself and his family.

Closure is also something that the main character in Jeff Lemire’s The Underwater Welder desperately needs. This dark, depressing, and superbly presented story follows Jack Joseph, a welder for an oilrig off the coast of a sleepy New England town, in the days leading up to the birth of his son and the anniversary of his father’s death. The confluence of these two events thrusts a tremendous amount of emotional stress upon Jack, causing him to have a psychological breakdown that forces him to confront suppressed memories from his childhood. What follows nearly costs Jack his life, while at the same time giving him a chance to create a happy life for himself and his family.

Lemire’s art is both stunning and frightening. The monochromatic illustrations give the piece the feel of, as Damon Lindelof describes in the introduction to the story, “the most spectacular episode of The Twilight Zone never produced.” Nearly all of the events in the story take place at night, or underwater, isolating Jack from the outside world, mimicking the emptiness that he feels inside. And for a portion of the story, Jack exists only to himself, creating a frightful loneliness for both Jack and the reader.

The stylized and graphic depictions of the characters also speak to the isolation of Jack. The other characters in the story are more animated and expressive than Jack is. When it comes to Jack, however, his lack of expression, and deep, hollow eyes reflect the fear and loneliness he is experiencing. He comes across to the reader as a man standing on the precipice of nothingness and there is nothing we can do but watch him fall.

The stylized and graphic depictions of the characters also speak to the isolation of Jack. The other characters in the story are more animated and expressive than Jack is. When it comes to Jack, however, his lack of expression, and deep, hollow eyes reflect the fear and loneliness he is experiencing. He comes across to the reader as a man standing on the precipice of nothingness and there is nothing we can do but watch him fall.

And fall he does when he finds an old pocket watch under the water at the oilrig. The watch triggers memories of the days leading up to his father’s death, but Jack feels there is something more to the watch. He obsesses over the watch and his father. Jack goes so far as to dive alone, at night, to try to find the watch again. During the dive Jack has what can be best described as an out-of-body experience that exposes Jack’s dark truth: in a fit of anger, Jack threw a pocket watch that his father gave him into the bay. Jack’s father died trying to recover it on Halloween. It becomes clear that subconsciously Jack hides this particular memory by creating for himself an image of his father as a hero, an adventurous man who could do no wrong. However, the flashbacks that Jack experiences and the memories that resurface pull back the layers that Jack has wrapped around his father and expose the deeply flawed man that Jack’s father was.

The realization of the affects of his actions simultaneously brings Jack farther into the darkness and guides him to toward the light. Jack realizes “now I’m the one who’s missing” and that “maybe I can still change things . . . Maybe I don’t have to be a ghost too.” This revelation gives Jack the ability to find closure with his father’s death and to return home to be a father to his new son instead of a ghost.

The realization of the affects of his actions simultaneously brings Jack farther into the darkness and guides him to toward the light. Jack realizes “now I’m the one who’s missing” and that “maybe I can still change things . . . Maybe I don’t have to be a ghost too.” This revelation gives Jack the ability to find closure with his father’s death and to return home to be a father to his new son instead of a ghost.

The combination of written text and illustration that makes up comics engages the reader both visually and aurally, allowing reader to both see and create the voices of the characters in the story that is being told. This helps to immerse the reader completely into the world being presented to them, creating a more impactful story, and connecting with the reader on a deeper level than most traditional forms of storytelling. Comics now are what theater and traditional literature were and still are: an accessible form of entertainment that can convey simple stories for the sake of entertainment, or can present topics with deeper meaning and purpose.

The combination of written text and illustration that makes up comics engages the reader both visually and aurally, allowing reader to both see and create the voices of the characters in the story that is being told. This helps to immerse the reader completely into the world being presented to them, creating a more impactful story, and connecting with the reader on a deeper level than most traditional forms of storytelling. Comics now are what theater and traditional literature were and still are: an accessible form of entertainment that can convey simple stories for the sake of entertainment, or can present topics with deeper meaning and purpose.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Palestine could be an important journalist work, but unfortunately IMO it feels like it is treading the thin line between journalism and propaganda.

Jess Fink is an amazing, funny badass.

My only complaint would be that the book feels a little bit disjointed.

I thought Palestine was a fine graphic novel, serious, thought-provoking, and using the medium in a original and valid way.

I really enjoyed Underwater Welder. Not too many characters or highly complex story lines, just a solid well done graphic novel.

This is certainly an informative article about how comic books can delve into different narrative structures beyond the cliche superhero narrative.

In the 50s, Wertham’s “Seduction of the Innocent” campaign gutted the American comic publishing industry… though to be fair, most of the publishers of the time colluded in order to kick out William Gaines, who was out-selling them. But the end result was that Americans became convinced that comics really were only for kids, as though an entire medium could be so reduced. Everywhere else in the world where comics are read, they have been treated as any other story-telling medium and not denigrated as they are here.

Probably preaching to the choir here, but thanks for helping spread the message the the medium does not have to be defined by a single genre.

It is interesting how comics have been as compartmentalized in the U.S. as they have. But you.re right, Wertham had a HUGE part in that, almost killed the industry. I still need/want to read his “Seduction of the Innocent” though, just out of curiosity. Probably reads like some Cold War anti-Communism propaganda.

Actually, while Wertham did play a major role in censoring the industry by bringing comics to Congress’s attention, Wertham was not at all an anti-communist, certainly not a McCarthyite. Yeah, the comics scare went down at the same time, and as a cultural event, may certainly have been tied to a cultural paranoia about the “sanctity” of American childhood, but Wertham was himself a rather radical intellectual. But because of his pop psych book and his damming view of comics, he is only remembered as “that guy.” This is one of those cases wherein it makes more sense to read criticism of Wertham than it does to read Wertham; see especially Bart Beaty’s book, “Frederic Wertham and the Critique of Mass Culture.”

Monique, I’d like to point you to a collection of essays, edited by John A. Lent, published by the Associated University Presses in 1999, called “Pulp Demons: International Dimensions of the Postwar Anti-comics Campaign.” Though it has a gaudy cover, the essays are phenomenal (and you can view most of them via Google Books). This book shows that this post-war anti-comics crusade was not specific to the United States, but occurred in most Western nations and the British territories, including Australian. There is also a great book, albeit in Swedish, about the same phenomenon in Sweden in the 1950s. It simply isn’t true that “everywhere else in the world where comics are read, they have been treated as any other story-telling medium.” While comics readership is certainly higher in Japan than in America, manga has not been without both its legislative concerns there and its own conservative backlashes. Moreover, I think it’s worth noting that the vast majority of comics studies comes out of the U.S. and France/Belgium, two places that have in the past three decades seen a renaissance of interest in general comics readership, and a continued laugh at superhero comics as childish.

You know, even though Sacco refers to his work as a comic it is clear that he was profoundly affected by his visit, and he has definitely produced a worthy record of it.

Yes! I considered writing something like this myself not to long ago. But you explored the topic very well! I hadn’t thought about using the graphic medium for biography. I have to check some of these out!

Using it for biography is cool, especially if the author is drawing it as well. It’s interesting to see how people perceive themselves in their artwork.

Hi! Loved your article. Really interesting. Wondering if you had heard of Manga Shakespeare? I took a Shakespeare class last year and did a lot of research on this genre. It’s a reinterpretation of classic literature (and classic with a capital C I suppose, as Shakespeare is our arbiter of taste in all things literary). I’d love to hear your thoughts!

I have not heard of Manga Shakespeare. To be honest, I’m not a huge Shakespeare fan (thanks high school English classes), but the Manga aspect could make it more enjoyable.

Oh yea, The Underwater Welder is incredible. I started reading it with hot tea and a warm cookie. By the time I put it down, I had completely forgotten and was left with cold tea and a hard cookie.

Lovely post. Lemire is a great storyteller!

Cool article, and I do want to check these out. However I can’t help thinking; ‘why can’t comics with superheroes have “literary value”?’ Sci-fi (which is what most superhero comics are) is great at dealing with socio-political/philosophical ideas, the difference is they do it subversively, through metaphor/allegory *cough* Watchmen *cough*. This article implies that you don’t think superhero comics can have literary value, which I very much disagree with.

I do think that comics with superheroes have literary value (one of my favorites is Spider-Man Blue by Loeb & Sale). I feel that a lot of the literary value of comics is either overlooked, or tainted by the presence of superheroes causing the perception that comics are just fun stories without much merit or value. I agree with your comment that comics are a lot more subversive in how they approach topics, which is another issue altogether. Basically, my point is by removing the “distraction” of the superhero from a comic or graphic novel, the commentary that the piece presents becomes more noticeable.

I’d like to see you back that up. How, for example, does the commentary become more noticeable in Spider-Man 2099 if we take Spider-Man out of it? You seem to be conflating “noticeability” of commentary with literariness, which seem contrary to the reality of most works considered literature, where sufficient polysemy (ambidguity of direct reference) is required in order to keep interpretation alive across generations of readers (I believe that’s Adorno’s argument, but I could be wrong). I also don’t think literature necessarily needs to be commentary, in that it provides opinions; but literature also becomes that for which there can be commentary. Comics of the late 1980s and the 1990s are a prime example of an era sufficiently filled with polysemy, crisis, fear, overextrapolation of the superhero’s being and body, etc. to provide hundreds of pages worth of analysis.

My favorite non-superhero comic to recommend and lend out to my friends is Daytripper.

Interesting article! I completely agree with you. I was raised to comic books but none of them were about superheroes and that didn’t change their value. They were as entertaining and funnier than Marvel Comics (they are great too by the way). Not long ago, I read Persepolis and absolutely loved it. It was so pertinent. I took it more like a journalistic documentary on a young girl of my age witnessing political and religious authority to its extreme and seeing it destroy her dreams. I am going to study Palestine this year, really excited about this, I’m sure I will love it. A comic book can be as powerful as a ‘serious’ book.

I remember reading Maus for class in college and being blown away by the literary and academic value graphic novels can have. Great article, I’m going to have to chec some of these titles out!

Maus is still my favorite to date. It is one of those that is not necessarily an enjoyable read because of the content, but it leave an amazing impact on the reader.

I did not discover graphic novels until college, and I have not stopped loving them since! I suggests them to my reluctant reader students, and I’ve had no complaints yet.

I didn’t become interested in comics until I was -taught- comics. For some reason, as a viable form of medium, I began to take interest in them — huge interest. I’ve currently been writing reviews, and working on a script myself. I have also considered applying to a PhD program at the University of Florida with a specialization in Visual Rhetoric and Comics. A university in my state (West Virginia) has one of the “pioneering” graphic novel majors, in which students specialize in art and storytelling to create comics; it’s truly blown up recently.

Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi was the first graphic novel I’ve ever read, and I thought I would hate it, but actually I think if done right, it’s an amazing strategy to deliver these deeper messages about controversial topics. It was a great read.

I like your article a lot. I love comic books, particularly ones based on literature or conveying literary stories. Now, a lot of the super hero comics are also using political and social topics as part of their storytelling.

Can we please give Transmet some credit one day? You look for what a non-super can do to give the mass some justice look at Spider Jerusalem.

Being able to incorporate art and storytelling together to create a fluid and interesting storyline-whether with or with out superheroes-can be a difficult task. Whenever someone doesn’t consider it literature or sees it as “childish” they’re discounting a medium that has great potential to deliver a message in a way that no other genre can.

A good essay. I wrote an article on graphic novels several years back and did not know they have a long history.