Why Do Readers Enjoy The Detective Genre so much?

Detective fiction as a subgenre of crime fiction arose in 1841 with the publication of The Murders in the Rue Morgue by Edgar Allan Poe. It was through the eccentric character of Auguste Dupin that the word ‘detective’ entered the vernacular of the English language. You can see elements of Dupin in future depictions of the ‘detective’ – a character who uses deduction to figure out the answer to the mystery.

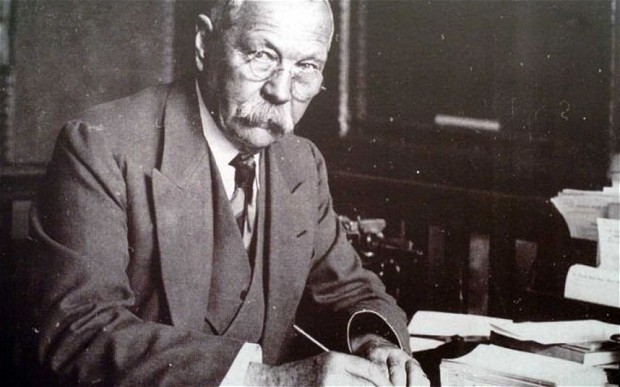

While Poe created the genre, it was Arthur Conan Doyle that ensured its continued success in the world of literature. Doyle wrote 50 books with Holmes and Watson. The popularity of these books was so great that when Doyle sought to end the story of Sherlock Holmes, there was such a public outcry that Doyle brought the famous detective back to life, although begrudgingly.

Study In Scarlet was released in 1887 and since then, the number of books published as detective fiction has only grown. People enjoy writing it just as much as people enjoy reading it. However, this brings us to the question of why.

Why is this genre so popular? What was it about the character of the detective and the mysteries they solve that spoke so strongly to the populous?

A similar phenomenon can be seen in true crime shows and podcasts, which have grown immensely in popularity since the introduction of streaming services. As these shows take a narrative turn to convey the story of these crimes, they are usually similarly structured to a book – each episode a chapter, ending with a cliff-hanger to keep you watching. As such, we can relate our psychological responses to these shows to books.

In an article for Rasmussen College, Janice Holly Booth, author of A Voice Out of Nowhere: Inside the Mind of A Mass Murder, suggested, “We all possess a dark side, although I would say most are light grey as opposed to inky black, and maybe that’s why so many of us are obsessed with the sinister doings of others.” Whilst attorney Marc Lamber said, “Because crime is foreign to most, the fascination with it and similar genres stems from the public’s curiosity regarding what would possess others to engage in criminal conduct, what it looks like and what happens as a consequence.”

Though there is a line between fiction and reality, both can be considered ‘safe ways’ to address the macabre. Professor of Sociology and Criminology Scott Bonn explained in Psychology Today, “As a source of popular-culture entertainment, serial killers allow us to experience fear and horror in a controlled environment, where the threat is exciting, but not real.”

There is also a want to find out more to protect oneself. Amanda Vicary, associate professor of psychology at Illinois Wesleyan University, told Huffington Post, “By learning about murders — who is more likely to be a murderer, how do these crimes happen, who are the victims, etc. — people are also learning about ways to prevent becoming a victim themselves.”

While there is the psychological impact of the topic, there are also literary choices that an author makes. Perhaps one of the most important would be the person the author chooses to tell the story from. If we were to read Hound of the Baskervilles in Sherlock’s point of view, chances are the story wouldn’t have the same effect. The character of Sherlock Holmes is brilliance. He is the always the smartest person in the room. He notices things and deduces in seconds. Would the books continue to be as interesting if we knew everything in moments after a page of exposition? It is unlikely.

This is where Watson comes in. A character that Poe lacked in his three Dupin stories, John Watson is the reader character within the book. They are the character that helps carry the audience through the story. According to an article by Sanford Binns, “Holmes would have been explaining his thought process as he went along, thus solving the case in the middle of the story for himself, rather than solving it for the reader at the end. Furthermore, Holmes inevitably would have been calling attention to his own intelligence, thus appearing insufferably conceited and hence unappealing to the reader. Superior intelligence is a more appealing trait when it is observed by others than proclaimed by the savant himself.”

In any story, the reader-character needs to ensure empathy between themselves and the reader. In the example of Sherlock Holmes, Watson’s lack of analytical deduction skills is a benefit to the story.

That isn’t the say that telling a story as the detective doesn’t have the same impact. The most iconic of murder mystery authors is Agatha Christie, a woman who wrote countless stories in the point of view of many different detective characters. Poirot and Miss Marple aren’t fantastical investigators with borderline superhuman abilities but they are good at piecing clues together. As you read, you are piecing them together as well, making reason and deductions at the same as the detective themselves.

These stories are told from third person omnipresent rather than first-person, thus allowing Christie to jump around, reveal to the reader clues to solve the crime before the detectives themselves.

Arguably, this is part of the draw of detective fiction – trying to figure out the crime before the detective calls all the suspects into the room and points a finger at the perpetrator. But why is this so effective?

Christopher Badcock, author of The Imprinted Brain commented in Psychology Today, “the remarkable success and continuing fascination of detective fiction might find an explanation in the way in which it combines extremes…Paranoid suspicion and credulity for conspiracies is wholly appropriate—particularly in murder mysteries—and naming, blaming and shaming—a crucial if cruel mentalistic tool where influencing others is concerned—is epitomized in the revelation of the culprit on the climactic final page of the detective novel.”

A successful and rememberable piece of detective fiction can be made by the skill in which the author releases information for the investigators and the reader. A big reason for this may be because of the brain and its relationship with puzzles. Marcel Dansei, professor of semiotics and anthropology at the University of Toronto, said, “Puzzles play with words, numbers, shapes, and logic in a way that impels us to uncover the solutions that they hide. We are thus engaged in a mental hunt for something, much like a detective in mystery stories or a scientist looking for the reason behind some phenomenon.”

This may also have an impact on why readers may feel cheated if foreshadowing and red herrings aren’t appropriately used in a story. Dansei added, “Puzzles are small-scale versions of this ‘quest for understanding,’ even though there is nothing new at the end of the hunt when a solution is uncovered. It is the hunt itself that is likely to stimulate various areas of the brain that involve discovery and a sense of satisfaction at once.” A disappointing or inadequate journey to the climax of a detective novel will make the entire story lackluster.

So why do we enjoy the detective genre so much? It is a combination of curiosity into the darker side of humanity that influences our general interest into true crimes and murder mysteries. Our brains want to connect pieces together to solve the puzzle innately. In terms of literature, it is about the skill of the author to ensure that readers have to correct information, at the right time, to solve that mystery.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I think people crave a coherent narrative in which good triumphs over evil, reason over senselessness. When I’m feeling down I always turn to Conan Doyle or Margery Allingham so as to escape to a world that makes moral sense

Not all crime novels have good triumphing over evil.

In times of suspicion, doubt, and mistrust crime novels flourish: look at when Hammett and Chandler were at their biggest. Namely, in the wake of the 30s.

Crime novels are one of the few genres where you get to see the top and the bottom of society: a detective can pass between the worlds of Kings and cut throats being one of the few jobs, especially if you work for the police, you can meet all walks of life and probe them in the same way.

Crime novels at heart often show what lengths people will go to get money: how having, as much as not having, money distorts peoples personalities.

Also, crime novels at their heart, have a riddle which layer after layer gets stripped away as you read. Some of the truly great novels put the answer right in front of you and challenges not to be misdirected.

Most of crime novels, the good ones, the great ones, make you feel that resolution of no crime is beyond your ability; it just requires that you display the elementary discipline of focusing on what is important whilst discarding the superfluous.

Most crime/detective novels are crap. But sometimes you get lucky and find writers that marry thrill/crime/plot with pretty prose: Saul Black, Peter Heller, John Hart, Brian Panowich, Steve Cavanagh, Karin Slaughter…

Anytime I look at the crime section in tescos it seems weirdly focused with violence against women. I’m sure commentators can provide numerous examples that aren’t but go see what’s being flogged and you can’t deny it’s all rather….. ugh.

That could be misogyny, or it could be a perennial miorbid fascination with sexual violence. What of those modern penny dreadfuls marketed at women that have covers plastered with the like of ‘Hubby Raped My Kids’ every week?

People have a fascination with the psycho-sexual gothic.

The majority of readers of such books are women, oddly enough. Many of the writers, too.

When there’s violence, and there usually is in crime novels, then it should be against women 50% of the time.

Unless there is a gender victim-of-violence-in-fiction gap. That would be outrageous

Nicely written. Why do we enjoy a decently written detective tale? Very simply, it stimulates and exercises those ‘little grey cells.’ Thanks for the fun read.

Definitely the challenge of finding out “whodunit”. I read many of Agatha Christie’s novels, and I never guessed the culprit 99.99% of the time! (Got it right once, but couldn’t figure out motive.)

A good detective movie to watch is Knives Out. Has a very Agatha Christie-y feel to it.

Crime novels, by definition, are always about morality. What is defined as a ‘crime’ is always the starting point. Against this there is the protagonist and how s/he presses or compromises this view of morality and indeed creates her/his own. I find it interesting that we are seeing more novels appearing set in authoritarian and totalitarian regimes (they have been around at least since ‘The Cowards’ (1958) and ‘Gorky Park’ (1981) and are seen in things like ‘The Secret Speech’, ‘Prague Fatale’ and ‘Stasi Wolf’ today. These add that extra element in that there is an assumed human morality; the morality developed by the detective and then the morality determined by the state. These novels are almost the flip side to the original hard boiled novels in which the detective was going up against corruption in a society which on the surface appeared to be peachy keen. They show the seedy ‘underbelly’ which would make Eisenhower/Kennedy era Americans shudder even while in theory safe in their context. In contrast now we look more at societies that were perverted in terms of morality because of their regimes and see the compromises by the detective away from such corruption towards a more human morality rather than the other way round. Perhaps this reflects our increased cynicism of how ‘good’ our society is.

Interesting. I like your definition and I tend to agree. One thing, did you mean ‘squeaky clean’ instead of ‘peachy keen’ or am I missing some kind of outre hard-boiled vernacular?

Hardboiled is great. Noir even better. I think the reason they are still popular is they offer something far darker and edgier than the endless conservative police procedurals that clog up the charts.

I’ve got a passing acquaintabce with this genre. Love Raymond Chandler and Jim Thompson, mixed feelings on Dashiel Hammet, but I would like to read more and if anyone has recommendations they will be gratefully received.

My tip for anyone who hasn’t come across it would be The Last Good Kiss by James Crumley.

Try the series of LA set Bosch novels by Michael Connelly (recently adapted into a series by Amazon); recognisable archetypes but also contemporary (he began the series in the ’80s). Bosch is a great dark knight.

John D MacDonald’s Travis McGee novels are one of the undisputed best investigative series ever written, and finally, Lawrence Block’s series and non-series work is tremendous fun too.

The best crime novels of the moment are John Connelly’s Charlie Parker series – works of art. They have a supernatural element that may put some off.

The best wise cracking PI is Robert Crais’s Elvis Cole – The early books in particular are wonderful and clearly influenced by Chandler.

Michael Connelly’s Bosch novels are indeed good – he’s a complex hero, quite hard to like in many ways, which means writing a best selling series of novles about him quite a feat. “everyone counts or no-one counts” – Harry’s mantra.

Read Hammett’s RED HARVEST.

A friend, when feeling a bit depressed, was advised by a neighbour not to take antidepressants but to read an Agatha Christie. Sound advice. I’d also recommend Mary Stewart’s romantic crime novels, starting with ‘The Moon-Spinners’. At present, reluctant to watch any television news and seeking escape, I’m reading Trollope’s Barcetshire novels, which are very entertaining & gripping, where the baddies, like Obadiah Slope, are punished.

I think it’s because detective novels usually have something called a plot. Makes one turn the pages to see how it unfolds.

Literacy fiction should look into the amazing feature that is the plot. Readers love it.

I do like a good detective story but most modern Crime novels are about murder, usually serial killers and often sexual assault/rape. Are there any well crafted detective novels about car theft, robbery or dog fouling. Ok that last one maybe a stretch too far but we do seem obsessed with murder

It’s a pretty wide genre. The best crime book I read was Homicide by David Simon, which was actually true crime, but so well written it reads like a novel, only no novelist could think up those plots. At the other end of the spectrum are the Father Brown stories by G.K.Chesterton, which are as far removed from real crime as it is possible to get.

Fantastic book and the basis for two of the best series ever on TV, Homicide and The Wire. You’re absolutely right. The writing is top drawer and I reread it every couple of years.

Let’s not forget historical crime – I started with Cadfael as a teenager and have adored the Falco series for years. Possibly lowbrow but I also confess to a real weakness for alternative history and sci-fi crime. I would dearly love to see Asimov’s Bailey/Olivaw series brought to the screen.

I have not read any Asimov for years, you have reminded me how good they were.

You could never call Asimov a great writer-most of his work are just men talking in a room. But the ideas he works through are brilliant.

The naked sun was done in the 60s in Out of the unknown, but that and Caves of steel would make stonking movies.

I like crime novels – I’m current working my way through the Morse novels (sourced the entire series from charity shops) and I love Sayer; I even read Reacher novels (if I find one abandoned in a hotel) but I couldn’t get further than the first few chapters with two of the books praised here – Gone Girl and Girl on the Train.

My favourite crime novel is Emil and the Detectives – I’ve read it it many times.

Any recommendations along the lines of Carl Hiaasen, Donald Westlake, Chris Brookmyre or even Janet Evanovich? Humorous crime capers in general? There’s enough misery out there in the real world!

Try Kinky Friedman, former lead singer of the Texas Jewboys. His books feature a detective named, um, Kinky Friedman. You get the idea. Extremely funny.

I’ve read quite a few Carl Hiaasen books, I found them really funny but I seem to have exhausted the supply from our local libraries unfortunately.

I very much enjoyed the Lawrence Sanders Archy McNally series too, about a private eye in Palm Beach. Also very amusing.

Love detective novels, particularly James Ellroy, Carl Hiaasen, Elmore Leonard, Umberto Eco, and Ian Rankin.

Almost all TV drama has been crime drama for years, so perhaps books are just playing catch up.

There are a great number of excellent detective novels. My favorite detective novel is L.A. Confidential by James Ellroy (also an exceptional and distinct movie too). In addition, many elements of detective stories have begun to cross over genres to other genres. For example the recent novel “The Last Smile In Sunder City” by Luke Arnold mixes fantasy setting with more pulp detective plot structure. It’s a really interesting detective read for people looking for something a little usual!

Very good. Discussing the relationship of detective stories to puzzles, nice connection.

The great thing about the ‘crime’ genre is that tension/suspense is built into it. Less danger of the writer fannying around with ‘meaningful’ prose riffs.

I definitely agree with your point that there is this shared sense of wanting to understand the perspective of different personalities or situations people are placed within. The investigation genre provides insight on not only the strictly “evil” people in the world because of course not everyone can see in the perspective of the said “evil” character, or not everyone can be wholly evil (except few). Stories like Sherlock enables me to understand the personality or the experience of life’s torments of that antagonist that moulded or developed the character. Personally, I love a story that applies a combination of real killers into a single character. The silence of the Lambs, for example, is a remarkable thriller mystery that depicts an investigation into a serial killer by a female investigator that interviews a convicted killer/cannibal to understand the behaviour of the new killer.

As someone who has, well, no interest in the detective genre, this is really insightful! I can definitely understand the appeal. Great read!

Good work! I love a detective story good enough for me to “play along,” and conversely, I dislike ones that are too easy to figure out or do not use clues appropriately.

This is an insightful read! I love it when detective stories include the “right amount” of puzzlement for readers/viewers. Ones that aren’t too dense and go over the audience’s heads, but also aren’t predictable and easy to unravel from the get-go.

An avid detective fiction reader myself, I found it great fun reading through your article and recollecting all the wonderful moments I had spent reading the works mentioned. Thanks for the quick trip down memory lane which made my day.

Always been a fan of Sherlock Holmes. This article was an exciting read and made me dive into my obsession with the genre.

Naming, Blaming and Shaming .. isnt that what ‘we’ use Social Media for now?

I’ve never enjoyed true crime much, but have always had a fascination with fictional detective stories. In elementary school I checked out two Nancy Drew books at a time until I cleaned out the shelf and then, when I was allowed to check out from the YA section, I discovered an Agatha Christie collection. I was slightly horrified at first by some of the murder descriptions (tame by today’s standards), but I couldn’t put them down. I loved the Sherlock Holmes and No. One Ladies Detective Agency stories too. There is something about solving a fictional mystery that stimulates and engages the reader without alienating them––I always feel that I am the one doing the detecting. With true crime I want to distance myself a little bit more and knowing that it is a real event makes me less inclined to believe I can or should try to immerse myself in it enough to feel that I am the one solving it. Great article! Thanks for sharing.

A good essay. A nice explanation on enjoying detective stories.

A lovely essay. As a big fan of the genre both in print and on screen, I want to say a reason I am personally drawn to the genre is that it’s also very radical to attempt to humanise the antagonist of a crime–to learn why they did it, to discover that all the clues that didn’t tell us how it happened actually painted a clear but seemingly secondary picture of why it happened, and to discover what corner the murderer was backed into that made their bad decision the only option left for them. Just reading this essay made me want to go digging for my copy of Tana French’s ‘The Likeness’ to re-read.

Agatha Christie’s my fav.

I read a crime novel for the first time, I usually see the movies, but one day I saw a book and decided to read it, I was impressed.

What I find so fascinating about detective stories is the detective character exists purely for the benefit of other people’s stories. The true main characters in the story are either dead or criminals trying to hide their involvement, so the plot can only develop if another character shows up to point out the clues.

TV adaptations of Sherlock Holmes have amped up the drama of his struggle to maintain relationships with his brother and friends. But in the original books, Holmes barely had a life outside of work, and that was okay, because the majority of each story was taken up by other people telling their stories, with Holmes just listening quietly. Then he would spend a couple paragraphs pointing out the relevant details and what they meant. Altogether, it doesn’t seem like a strong formula for a great character or a great story, but it works for all the reasons you described. Well done.

Poe didn’t lack a Watson-character in his detective stories. It was the narrator. They become friends and worked together.

As a criminology student, I am happy to see my studies in finding motivations for offenders to commit crimes make its way to the wider audience through detective stories in pop culture

I did like this little article, as I am a big fan of detective fiction and have read the seminal works in detective fiction over and over. I’ve always detective fiction more engaging than crime fiction because it mimics the way we burrow underneath things we don’t understand and the way we make mistakes, according to our own little unique foibles. Yes, definitely there is the pleasure of curiosity satisfied in fantasy, but I think this way of looking at it more belongs to crime fiction than detective fiction. The biggest difference for me is how detective fiction makes destruction, ordinary. It brings down crises like a lemon slice, to a nibbling portion, and can do that because it’s contained almost wholly within the limitations of its characters. So we don’t get so exposed to all the implications of the events or the crime itself in a broader sense. Nice exploration, and nice topic, thanks for sharing 🙂

I did like this little article, as I am a big fan of detective fiction and have read the seminal works in detective fiction over and over. I’ve always detective fiction more engaging than crime fiction because it mimics the way we burrow underneath things we don’t understand and the way we make mistakes, according to our own little unique foibles. Yes, definitely there is the pleasure of curiosity satisfied in fantasy, but I think this way of looking at it more belongs to crime fiction than detective fiction. The biggest difference for me is how detective fiction makes destruction, ordinary. It brings down crises like a lemon slice, to a nibbling portion, and can do that because it’s contained almost wholly within the limitations of its characters. So we don’t get so exposed to all the implications of the events or the crime itself in a broader sense. Good exploration:)

Not sure who was responsible for the photo captions, but Raymond Chandler did not write The Maltese Falcon, Dashiell Hammett did. Bogart played Hammett’s Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon and played Chandler’s Phillip Marlow in The Big Sleep