John Wick and the Empty Identity of the Action Hero

Across the neo-noir world of the John Wick films, there is a running joke that the swath of death and destruction left in the titular hero’s wake is the result of the killing of a puppy. It is a joke rooted in the absurdity of the answer, debatably, being yes; the killing of the dog given to Wick as a post-mortem parting gift by his beloved late wife can genuinely be considered the inciting incident that lead to the legendary killer’s return to the hitman business. As of the most recent installment, John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum, 306 deaths can be attributed to the killing of Wick’s first puppy 1 This is, by all accounts, one deadly dog.

The reasoning is, of course, more complex than the pithy question of “all of this over a puppy?” suggests. The dog is a symbol of the love that motivated Wick to leave the murder business in the first place. The “Impossible Task,” a vague act referred to in all three films that catapulted him into the status of legend among killers, was done to settle the debts that kept him in the criminal world and away from the woman he loved. After her death, he is left utterly alone – until, that is, the dog shows up on his door. As Wick himself explains, by killing the dog Iosef took away his only “semblance of hope… an opportunity to grieve un-alone.” 2 The dog was both a present companion and a connection to the world outside the assassin’s world. He seeks revenge not just for the life of the dog, but for the memory of his wife and a point of validation of his own existence. By killing Iosef, Wick avenges his whole world.

By this most recent installation, however, the dog fades further and further into the past, and the reasoning behind why Wick keeps killing, and keeps living, comes into question. Excommunicated from the assassin society for killing on the protected ground of The Continental Hotel, the de facto safe house of all assassin-kind, and with an ever-growing price on his head, Wick is utterly alone and besieged on all sides. He is no less efficient or capable – as evidenced in this film claiming the second highest body count of the series – but the motivation for his fighting becomes more abstract. There is no revenge or justice being sought – Wick kills to live and lives, it seems, to continue killing.

Through the character of Wick, Parabellum is able to dive into the psyche of the action hero in a way that challenges a lot of what is taken for granted in stylistic thrillers of this kind. The film reveals a hollow man, stripped of any real identity beyond action, and forces him to forge a self in a world that at best is indifferent to him and at worst wants him dead. As Wick is forced to answer to why he goes on living, what is inside him that needs to survive, the film asks after what is missing in the action hero defined by actions rather than emotion. By pulling apart the focus, commitment, sheer will, Parabellum challenges the stereotypical action protagonist and demands that there be a soul underneath – and shows exactly how to find it.

John Wick the Neutral Man

Critical to understanding the mind that moves the body of Wick is the interpretation of his actions. Wick is a man of few words; despite speaking objectively more in Parabellum in his parlaying final favours from the few friends he has left, he spends a large majority of this film in a silence punctuated only by groans of effort and gunfire. This silence doesn’t mean he isn’t communicating. In this case, as cliché as it may be, Wick’s actions speak louder than his words. What they say goes some way to explaining why he says so little.

A crucial difference between Wick and the traditional action hero is in the emotional emptiness of his fighting. Though stoicism is a prototypical trait in the hero, Wick moves past stoicism into a kind of mechanical efficiency. He does not spit out the witty one liners of traditional action figures like Die Hard’s John McClane or the caped heroes of the Avengers series; he does not roar in anger an agony like the gritty protagonists of recent DC fare or fellow neo-noir offering Sin City; his action, in effect, is not punctuated with humanizing passion. Rather, Wick treats combat as a binary. Everything is either threat or non-threat, active or inactive. His signature style of double-tap killing, a shot to the body followed by a shot to the head, emphasizes this – Wick simply moves from threat to threat deactivating them. There is no joy in victory or frustration in defeat, only continuation of movement until no further movement is necessary.

Despite the kinetic life of his fighting, the dispassion displayed points to an internal neutrality of being. His character refuses to shed the neutral mask, a theater technique pioneered by Jacques LeCoq. The neutral mask supposes an interior emptiness; as Sears Eldredge and Hollis Huston explain, “a neutral organism expends only the energy required by the task at hand […] at the moment of neutral action, one does not know what one will do next, because anticipation is a mark of personality.” 3 This is exactly the state of Wick as he navigates the world. He exerts only the energy required to kill and continue his path, his rapid improvisation (his penchant for non-traditional weapons including, but not limited to, a book, a pencil, and a horse reflecting this quick thinking) does not arise from meticulous planning or forethought but from its absence.

Though mainly coming across in his action, John’s dialogue, or the lack thereof, highlights his unfamiliarity with feeling. When Wick approaches The Director, the operator of an apparent assassin’s school that is implied to be the place of his upbringing, to request an escape from New York, she appeals to his feeling. 4 She stresses the danger that her helping him will bring upon the entire school, emphasizing the fact that in taking this ticket out Wick will sacrifice permanently the only thing resembling a family he may have in this world. Rather than engage, Wick simply restates the nature of his deal with the school; the tattoo on his back is a ticket that must be punched upon his request. It is not that Wick is callous, it is that he simply does not engage with emotion – a ticket is punched or unpunched, there is threat or there is not.

This is not to say that Wick’s interior absence is uncommon in the action hero, but merely more pronounced. Whether or not the hero kills with a quip, a roar, or in silence, the same equation is playing out as threats are neutralized. What Wick’s silence does is bring attention to this equation. In the silencing of the hero, the audience is forced to acknowledge the brutality and coldness of what the ostensible hero is doing. Wick’s silence draws focus to the lack of empathy necessary for the shoot em’ up protagonist – every action hero destroys his enemies and engages his allies to move forward, but Wick does it explicitly and without the veneer of passion. His hollowness is not uncommon, only clearer for its starkness.

Who is John Wick?

Parabellum is not content to leave this absence of identity unspoken (or in the things the protagonist leaves unspoken). Rather, Wick is forced to address the emptiness that ultimately undergirds his being. It is not enough that he kills efficiently and cannot be killed – though it is emphatically what he does, and the thing that has brought him into this situation, it is only what he does. Who he is should, but revealingly fails to, go beyond his actions.

The hollowness of the assassin is made clear in his brief interaction with The Elder, the only person with true authority over the High Table that governs the world of the assassins. The enigmatic figure is the only route Wick has out of the maelstrom that the contract on his head has made his life, but he stops him with a relatively simple question: why does he want to live? Wick’s answer is relatively direct and ostensibly emotional; he says that he fights to remember his lost wife, and killing him would stop this remembering. But, rather than allow this certainly acceptable response go unchallenged, The Elder unravels this statement, thereby unraveling what Wick thought himself to be. While his question explicitly “[d0] you seek to live for the memory of love,” the implicit question is much more personal: is living for the memory of another person already dead truly living at all?

Rather than having an identity that defines his actions, Wick attempts, though unintentionally, to create and identity out of his actions. He believes it when he says that he needs to live to keep the memory of his wife alive, but that belief does nothing to grant him a self. Wick is no more than an empty vessel that takes on external factors to manifest itself. He is the memory of his wife and his dog, he is killing three people with a pencil, he is a multi-million dollar contract, but he is nothing in and of himself. When The Elder commands him to remove his own finger to demonstrate his allegiance, the underlying emptiness is made physical; Wick leaves his wedding band behind, the physicalized memory of his wife sacrificed that he may keep living. While other films allow the audience to tacitly makes decisions on the identity of their heroes, Parabellum does not allow this engagement; in showing the hero be defined, the audience is not able to define him themselves, emphasizing the hollowness that ultimately characterizes him.

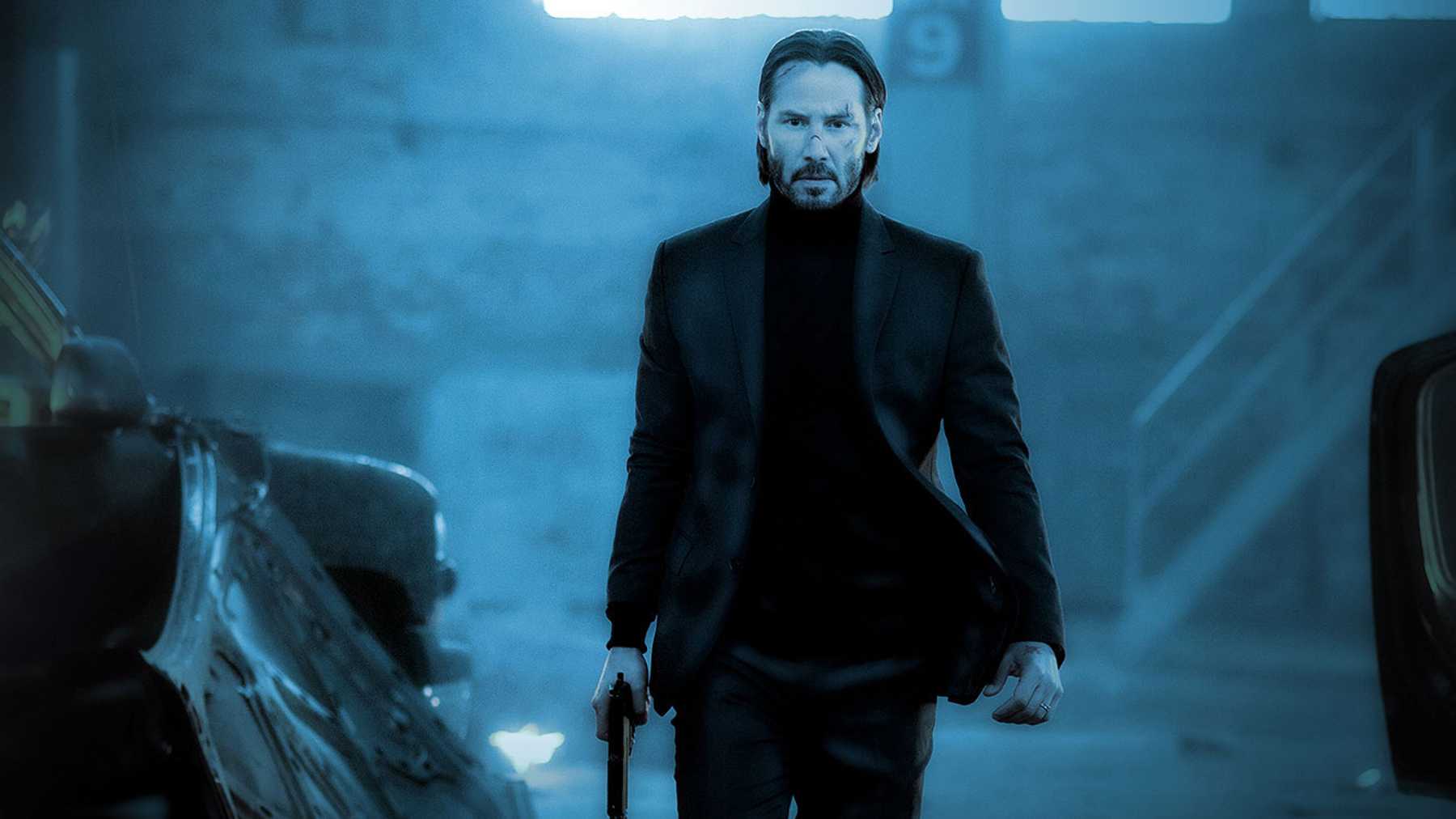

The final condemnation of Wick’s actions comes in the dress he adopts when he accept The Elder’s offer. As he sells himself back to the High Table in exchange for his life, among the gifts he receives is a new uniform in the form of a pure black suit. While Wick has donned just this kind of attire in previous films, a black suit being one of the first things he receives from his stash in the first film, this suit is fundamentally different in two key ways. First, it is not his: this suit is not one he chose, but one that is thrust upon him. In being a given rather than a chosen item, it emphasizes his new role as a tool of the organization rather than his own person; it his not John Wick’s suit, it is the suit The High Table put John Wick In. Second, and more importantly, in this moment the black is an indication of the interior of Wick. The black he wears externally reflects the gulf that is his interior world. All he is now is a black suit – in the absence of self-definition, he has allowed himself to be defined.

The final condemnation of Wick’s actions comes in the dress he adopts when he accept The Elder’s offer. As he sells himself back to the High Table in exchange for his life, among the gifts he receives is a new uniform in the form of a pure black suit. While Wick has donned just this kind of attire in previous films, a black suit being one of the first things he receives from his stash in the first film, this suit is fundamentally different in two key ways. First, it is not his: this suit is not one he chose, but one that is thrust upon him. In being a given rather than a chosen item, it emphasizes his new role as a tool of the organization rather than his own person; it his not John Wick’s suit, it is the suit The High Table put John Wick In. Second, and more importantly, in this moment the black is an indication of the interior of Wick. The black he wears externally reflects the gulf that is his interior world. All he is now is a black suit – in the absence of self-definition, he has allowed himself to be defined.

This black stands out all the more for the vibrancy and variety of colour in the world around Wick. Though certainly relishing in a persistent darkness, the film is punctuated by vibrant purples, greens, and blues. Wick stands out like a sore thumb against this; while he moves from the low green of The Continental lobby into the white lights and shining glass of the office of Winston, the disgraced owner of the hotel, he remains a stubborn black stain. There is life in the world, and Wick does not blend into it – he stands out in his standing for nothing.

Finding Self: “Are you pissed off?”

In the final act of the film, it is clear that what began as a fight for survival has become a fight for a reason to survive. Though given an ostensible new chance at life, Wick remains coldly dispassionate on his return to New York. He is no less physically threatening (one of his first acts being the killing of several assassins still desperate to take advantage of that bugbear of a contract), but his legendary will begins to show fractures of uncertainty. As he is asked again and again what he fights for, he is swayed far more easily than the man of commitment that lead the past films. This is not, however, the breaking of Wick, but his reforming; from the chaos of the climax of the film, Wick seizes a true and individual self.

However, this process of self-defining is not immediate. Rather, Wick’s first solution is to seek an identity that relies on the definition of other people. Upon reaching The Continental, tasked with killing his old friend Winston, Wick is stopped by the hotelier’s alternative offer. Rather than kill him, Winston suggests that Wick help him defend the hotel, fighting as his own person rather than as a cog of the assassin order; if he dies, he dies under his own power, no longer a machine to be deployed. This seems to be an out for Wick, and on the surface it is a rejection of one external definition, but, in truth, it is just another layer that ignores a central deficit of identity. As Sim notes, “the individual self serves as a default and primary form of self-definition;” 5 this definition does not come from within but, again, from without. He is not “John Wick” but simply “not the High Table’s,” defined by opposition rather than by himself. While this is an important step forward, it still lacks necessary self-definition. Wick is still defined by others, if not quite so directly.

As with the unspoken binary of threat, this definition by opposition is implicit, if unaddressed in countless action films. It is why charismatic villains are central to memories of classic features. As much as we remember John McClane, we certainly remember Hans Gruber; the calm, collected terrorist forms the antithesis of the no-nonsense police hero. McClane is defined in large part by not being Gruber: where Gruber is verbose, McClane is direct; where Gruber relies on elaborate plans, McClane is a master of improvisation. McClane, above all, is the anti-Gruber; his character is made from the character he is not. But this opposition ultimately proves tenuous in the absence of such strong antithetical characters – if they cease to be, the sense of identity they provide falls apart. Winston’s ultimate betrayal proves the fragility of this borrowed, oppositional identity. When he reveals that he only sought to prove his power to the High Table through enlisting Wick against them, the identity Wick thought he had is shown to be functionally unreal. His fall from the hotel roof reflects his fall from this borrowed sense of being. He was simply a cog in a different machine.

The moment in which Wick ultimately claims a character is in the closing moments of the film in which it seems that Wick has lost everything. Without his wedding band, without Winston, without a friend in the world, all Wick has left is his existence – one which at this point still lacks a center. It is fitting, then, that Wick finds himself at the feet of Laurence Fishburne’s Bowery King, ruler of the assassins that hide in plain sight as downtrodden, homeless citizens of New York. They find themselves in similar situations; both out of the grace of the High Table, both abandoned by the society they wished to live in, both on the lowest rung of the assassin’s existential ladder. Despite all this potential for the King to enlist Wick as he has been by Winston and the High Table before, to use him yet again as a weapon, he asks a radically different question: “Are you pissed off too, John?” He does not ask what Wick wants, what he plans to do, what he can do, or for help, but simply asks how Wick feels. Wick’s growled “Yeah,” like much of his toned down dialogue, speaks much more than the word alone. It is now his emotion that he speaks for, his emotion and drive that he acknowledges. What Wick is saying is “I am angry;” there is now an I that acts of its own accord, and that I is alive, feeling, and ready to assert itself.

The John Wick series is in many ways a prototypical action movie. The villains tend towards unambiguous and bureaucratic evil, the hero remains stoic, the henchman are faceless and nearly numberless. But Parabellum accomplishes what many films of this genre tends to ignore. It goes about building a character out of a prototype. Wick is not allowed to simply be cool, efficient, and violent. He is made to carve a soul from a place of absence, to define himself not by others, but out of and through himself. This multidimensional hero stands out in a genre that demands heroism and resilience by showing a different kind of strength. It seems that a lot can be done with sheer will.

Works Cited

- Evangelista, Chris. “John Wick Has a Higher Body Count Than Jason Voorhees and Michael Myers Combined.” /Film, 2019. https://www.slashfilm.com/john-wick-kill-count/ ↩

- Stahelski, Chad, and Reeves, Keanu. John Wick. Entertainment One, 2015. ↩

- Eldredge, Sears A., and Hollis W. Huston. “Actor Training in the Neutral Mask.” The Drama Review: TDR, vol. 22, no. 4, 1978, pp. 19–28. ↩

- Stahelski, Chad. John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum. Lionsgate, 2019. ↩

- Sim, et al. “How Social Identity Shapes the Working Self-Concept.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 55, 2014, pp. 271–277. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I like the ambiguity and normality of Keanu Reeves. And his film choices ranging from high and low culture makes him much more interesting than a lot of other actors. For us gen-Xers he’s an undisputable an icon. I loved reading about him.

I love Keanu Reeves and that is the end of it.

People like Keanu Reeves, and that’s rare for a Hollywood actor. There may be less there than meets the eye, he can’t speak a natural line to save his life, and it doesn’t matter a whit. He surfs a wave of good will.

I have a lot of respect for Keanu Reaves, he went though the hell of a lot. Beyond he usually picked his movies well and is always up to the role.

Brilliant entertainment! These films has everything: great action, chases, some very witty dialogue, a great soundtrack and a lot of style.

I think they shouldn’t make any more to be honest or finish it with no 4. The law of diminishing returns will set in.

Great read!

I really enjoyed the third film. Was nearly on par with no 1 and was much better than no 2. 2 suffered from the problem that it was all action, action, action with no downplay between the action and became repetitive. Loved the downtime in between the action scenes in 3 as this brought in new characters, developed existing characters and developed the world they all live in more.

The fight scenes are relentless and brilliantly done.

Nicely done. The injection of your own dark humour into the narrative works very well.

A good essay. When I watched these John Wick movies, I saw them as basically video games where killing was completely removed from reality. It does not take long to lose count of the numbers that are killed.

Well-written essay. Wick and others risk becoming a cipher with the films becoming “paint by numbers.” Many years ago John Barth pointed out in his essay “The Literature of Exhaustion” that genres exhaust themselves and either fade out or are re-invigorated; the re-invigorated genre maintains the conventions but expands/re-defines them. Of course, this can lead to the next level of exhaustion and the cycle continues. The genre may become unrecognizable because it re-defines itself out of existence

Next film, John Wick meets his match when his Father returns to reign in his son’s violence.

The Father played by Bill Murray.

looking forward to seeing the third one. parts I & ii are great. love a movie with keanu in it.

I accepted a while ago that the John Wick sequels would never be as good as the original when it comes to plot and drama, and I’m perfectly fine with that. As I see it, the sequels are basically detailing the aftermath of the event that is the first. The catalyst came and went, now it’s just ripples.

But what brutally beautiful ripples they are…

I’d love to see this Assassin universe connected to Léon’s through a grown and mature Nikita-esque Matilda.

Great insight into the franchise.

One thing John Wick brings back to action cinema is importance on establishing geography and building each action set piece until its climax. Many action films just blow their wads every scene, or pepper in money shots. The nightclub shootout is a perfect example of how to build a action scene. John goes with stealth, then when that goes to hell, he’s on stalk and locate, than finally gun’s blazing and he actually starts fatiguing and getting overwelmed which leads to him getting shot and his ass kicked. The action scenes tell stories. Its not just Wick running through everyone in cool ways. Also no shaky cam or constant cutting and Reeves does most of his stuff. You won’t be seeing a lot of Stunt Men when it comes to Reeves.

Good point on the nightclub scene. That is one of my favorite scenes in recent memory.

First and foremost, for me it’s the action and fight choreography. The way hand to hand combat and gun play is married together in these movies with such pristine and often times ground in reality techniques is just jaw dropping to watch, especially as he links kills together in a symphony of violence.

I get chills watching it.

The third movie massively ups the standard of the action. Somehow, they significantly improved on the first two.

Though I have some minor issues with John Wick 3’s story (won’t say what exactly because it means delving into possible spoilers), it’s still easily the best of the three.

If I had to rank them, I’d say 3-1-2. Though they are really all amazing.

The john wick movies are straight up well produced action movies. a homage to an earlier time where action dominated. we get maybe 1 or 2 action movies a year now and thats a good thing because that makes them more special.

These films are a great example of how it really pays off to have an actor that is willing to put the groundwork in. Reeves trained his ass off and it shows. They don’t need to use close cuts to hide his inexperience.

Excellent breakdown, looking foreword to reading your next article.

The John Wick series is getting worse and worse. I was really disappointed with 3.

I like to think of it as a one continuum story or episodic film.

I think it’s safe to say the John Wick Movies are the best western action movies in over a decade, they are just masterclass in how to frame & edit action films.

People like Micheal Bay & Paul W.S Anderson should watch these films a learn.

John Wick 3 offered some crazy versatility in terms of combat. Another good addition to the franchise and they are really fleshing out the world well! Halle Berry DIDN’T suck which was a surprise for me lol.

She never sucks, blame the movies.

It’s senseless kung-fu/Gun-Fu with Keanu. He just has a suave way of killing folks; Maybe it’s his clothing, or the fact that he’s done so many of essentially the same role. It was basically a solid 2 hours of action; and not in a Michael bay “explosions every 5 seconds” sort of way.

Keanu said he’ll keep making these movies as long as the audience wants them. I usually watch these movies at home, but since Keanu’s into it, I’ll throw some money at it’s box office.

I think what truly makes them stand out is simply the craft itself. the camera work, the editing, the attention to motion and space. Keanu is cool and all…. but imo it’s all about Stahelski and his crew.

Excellent in-depth break down of a character analysis. Never knew that an action-packed film could entail such profound message of the self concept. This article not only serves to make those who have seen John Wick proud for a good movie put together but also piqued the interest of those who have yet to watch the film.

I like that

Wick kills to live and lives, it seems, to continue killing.

You make an interesting point: that many action heroes, and particularly most of the iconic ones, have little in the way of personality and seem defined as much by what they are not or don’t have as by anything in particular that they are or do have. I wonder if part of the point is that there is something dehumanizing or unnatural about a guy who can just walk into a room and kill someone like it’s no big deal, even if that someone is a “bad guy.” Or maybe it’s an attempt to make the story seem more like a wish-fulfillment fantasy: if the character lacks personality it’s easier for the audience to live vicariously through him.

Excellent piece. I really like the idea of his physical violence as a binary reaction, based on instinct and survival. It really makes Wick stand out amongst the litany of action heroes.

Thanks for the essay! I liked 1st & 2nd John Wick, but rest are a plot less.. (it’s just an opinion)

John Wick is the violent edition of The Godfather.

I really liked the first one. Haven’t seen the second one though.

Very insightful article! I really like the slight reference to Keanu’s own life in John Wick 1 (as his wife and children (maybe the dog here?) died).

Interesting. survival is key to understanding many human actions. sadly his persona is like most of us reacting to his situation.

Pretty interesting read. Though I might have a different opinion on this.

John Wick, like so many other Hollywood “bad boys,” is supposed to be the “good guy.” But why? Is there really any difference between between Keanu’s character and those played by, for example, Liam Neesan? Clint Eastwood (apologies to Eastwood the director)? the late Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, and so on, or any other actor playing a specialist in extreme violence? The willingness to use highly accomplished forms of violence seemingly without any awareness that they have just killed (simulated) scores of human beings reflects the image of the ideal American man. As the poet Robert Frost once said, the image of the American man is that of a steely-eyed killer. Want to understand why the USA has so many mass shootings committed by young white men? In some respects critics of restrictions on guns are right: It isn’t so much a gun problem, it really is social attitudes towards the extent to which pitiless violence defines American manhood.

This role has done so much to revitalize Reeves in the eyes of a new generation, but I also don’t think it would have been as effective if he didn’t lean into the role the way he did, and didn’t have the history he already had as a “meme icon.”

I think he’s smart enough to know that too, which made him able to do what he had to for all the pieces to fall correctly into place.

Great read!

I do want to say, however, that even though the Bowery King does indirectly allow John to have a say in his fate and a chance to choose for himself, it’s essentially an thinly veiled ultimatum. He knows John feels betrayed, and he knows John will continue to kill to exact vengeance. It may not have been soon if he wasn’t rescued, but he would’ve eventually returned for Winston’s head.

Ultimately, the Bowery King took a gamble. There was a slight chance John would’ve said to hell with the tangled organizations of the assassin world, but the King knows John needs resources, and John knows it as well. I don’t think it’s radical to assume John wouldn’t have escaped the King alive if he denied his allegiance.

Great essay, though I need to rewatch all movies to be able to comment more. I do like how you pointed out the downward spiral that John was on until he finally reached the breaking point.

John Wick, Unleashes a quick kick

John Wick: Man of his word: All criteria tick,

One does not mess with him,

Unless you want your life to go dim,

A man of honour, focus and sheer will,

His name gives his enemies the chills,

Fortis Fortuna Adiuvat,

So tip your hat,

For here he comes,

Remember the name:John Wick.

Do not kill me with the pencil I used to write this comment.

On a more serious note, really liked your character analysis.

Yes, a lot can be done with sheer will. But the author fails to mention that money and favors are as important as determination. Wick couldn’t had gone so far without his fortune, his contacts, and the favors people owned him.

Wick existing as a character tied to others but at the same time empty, murdering for love and revenge but so far removed with so many bodies one has to ask what is really the motivator?