Men Written by Women: Dreamboats or Brutes?

The growing debate about the male gaze and the female gaze has impacted modern storytelling as well as changed our interpretation of past stories and characters. Just as some feminists complain about how women are depicted in books, movies, and TV shows written by men, an argument could be made that women do not know how to write male characters, either.

“Women love to write men who are just as unrealistic or lacking in depth as men love to write women. These male characters have no real personality and are measured only by their ability to satisfy the female character’s needs…”

Shelby Sullivan, “Men and Women Writing Each Other Badly,” medium.com

An analysis of various male characters created by women may show how valid that argument is.

The Classics

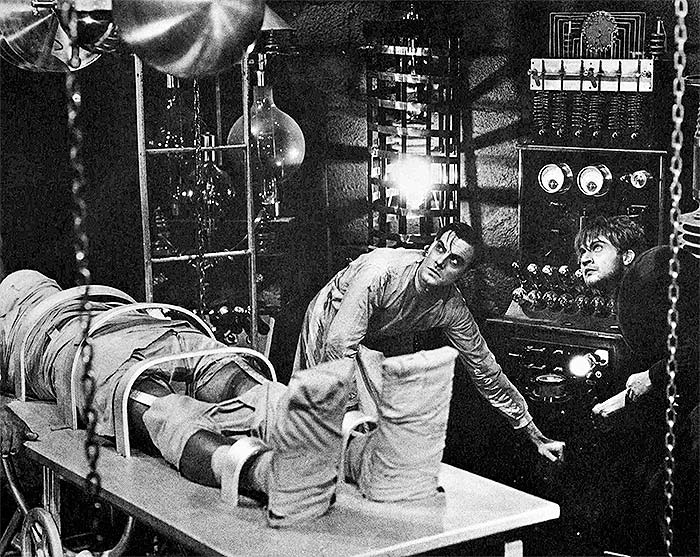

A significant number of literary classics were written by women. One such classic is Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. The novel’s protagonist, Dr. Victor Frankenstein, is brilliant but arrogant, thinking of himself as a god-like creator in his chosen scientific fields. Frankenstein is ambitious, but he does not take responsibility for the outcomes of his ambition; after successfully reanimating a corpse, he abandons the creature, labeling it a monster. After the Monster has killed people, Frankenstein attempts to hunt it down, but it is easy to guess that if he had been more responsible from the beginning, he could have prevented those tragic deaths.

“Even as he is dying, he will not admit fully to his mistakes, and the reader is left wondering whether it is Victor who is the true monster”

(GCSE AQA)

Frankenstein is an example of a male character who is not presented very positively by a female writer. Perhaps a male author would have tried to convince readers that he was a good person; perhaps, if he were created by a man, he would have succeeded in heroically stopping his Monster. It seems worth noting that the Monster is male as well, and although he develops eloquence and strong argument skills, he is driven by a primal urge toward vengeance against those who have mistreated him. Shelley seems to argue that this destructive behavior is a natural instinct of life itself, at least for male life.

In romance stories, the male leads are meant to be seen as very desirable, at least by the time the female leads fall in love with them. Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre: An Autobiography and Jane Austen’s novels, such as Pride and Prejudice, focus on female protagonists and depict men from a female perspective. In stark contrast to characters like Frankenstein and the Monster, some of these male characters have become the iconic dream guys for female readers.

Fitzwilliam Darcy is the leading male love interest in Pride and Prejudice. When Elizabeth Bennet first meets him, however, she does not consider him an interest at all. He is proud, moody, and rude. He has a long list of standards that a woman should meet to be worthy of his attention, and he openly shares it, ultimately insulting all the women who hear him. He makes a very unfortunate initial impression.

Meanwhile, the other main male characters in the novel – George Wickham and John Bingley – make much better first impressions. Elizabeth and her sisters take to them quickly. However, just as Darcy embodies Pride, Elizabeth is the Prejudice in the novel’s title. Her initial impressions turn out to be incorrect. Bingley makes mistakes in his relationship with Elizabeth’s sister, and Wickham turns out to be a manipulative liar. Darcy ultimately proves her wrong as well and proves himself a very suitable gentleman for her. In this way, Jane Austen makes the argument that charming men sometimes have rotten insides and that the best men are more than meets the eye.

Edward Rochester, the leading man in Jane Eyre, is another example of initial impressions being deceiving, although in quite a different way from Darcy. Where Darcy is reserved and haughty, Rochester is passionate, empathic, and friendly with Jane Eyre, despite being her employer. These charming attributes draw Jane to Rochester. However, it is soon revealed that Rochester’s passionate lifestyle has gotten him into trouble in the past, and his mistakes still haunt both him and his home. He is married to a woman with severe mental health issues, and to protect both of them from public shame, he traps her in his attic and keeps her a secret.

Thus, Rochester’s proposal to Jane seems less-than-genuine. He does genuinely love Jane, however. He is simply not ready for a relationship with her; he is too superficial, caring more about appearances than what is best for the women he loves. His reaction to his secret being found out is to suggest Jane become his mistress and offer her expensive clothes – this is also not healthy. It is not until Rochester has been physically disabled by the consequences of his passionate lifestyle that he grows enough to be worthy of Jane.

The Bad Boys

Although Rochester’s actions are bad, he is considered a Byronic hero or anti-hero. Unlike traditional heroes, these characters do not follow strict ethical codes. They are mysterious, dangerous, and flawed in ways many female readers find paradoxically alluring. Many famous male characters created by female writers are categorized as Byronic heroes.

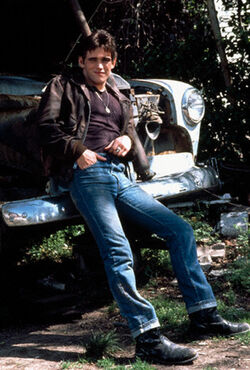

Another literary classic character turned Byronic anti-hero is Dallas “Dally” Winston from S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders. This book is about a gang of boys whose only bonds are with each other, and so even the most antagonistic of them is considered a good friend. This title falls to Dally. “He’s selfish, he’s dark, he’s rude, crude, and an all-around nasty dude” (The Artifice). And yet, it is revealed that Dally cares deeply about his friends. He risks his safety to save them, and when one of them dies, he feels such sorrow that he commits suicide by cop. Getting himself killed by the police preserves Dally’s tough guy image; only those closest to him know how emotional his friend’s death made him, which Dally would have considered a sign of weakness.

Like Jane Austen and Darcy, Hinton uses Dally to demonstrate that some men are better people than they first appear to be. However, unlike the classic romances, no female character falls in love with Dally because no female characters get to know him the way the readers do. Hinton’s argument is not only for women to question their initial impressions of men but for everyone to consider others more complexly.

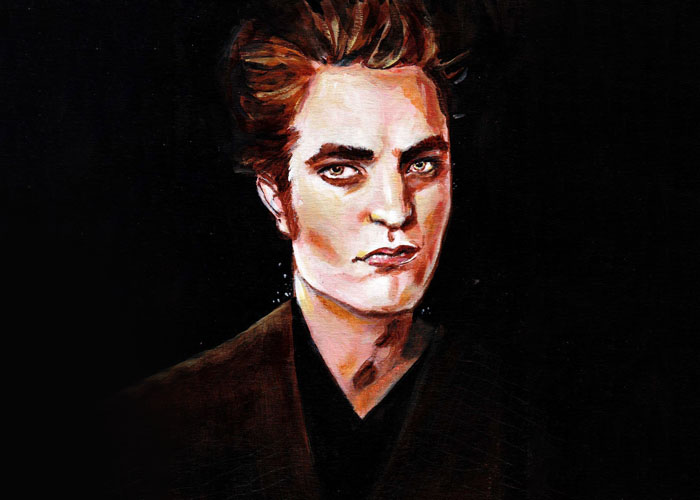

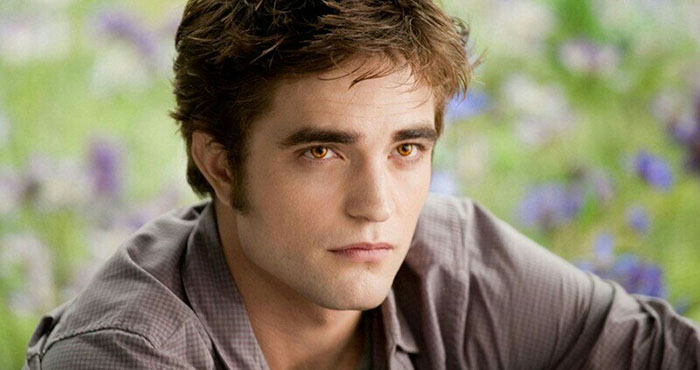

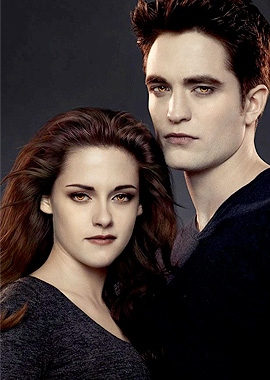

Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight, on the other hand, is a romance. The leading men of this series are Edward Cullen, a vampire, and Jacob Black, a werewolf. Edward is another Byronic hero, mysterious and dangerous, and Jacob is Edward’s rival for the affections of Bella Swan, the series’ leading female. Throughout the first book in the series, Edward assures Bella that, although they love each other, they should not be together because the risk of him killing her is too high. This is a noble decision that only makes Edward more attractive to Bella and the series’ audience.

However, Edward has many less noble qualities. When he first meets Bella, Edward essentially gaslights her, claiming that he did not do the suspicious and inhuman things she saw him do. Edward also displays stalker behavior, staring at Bella, eavesdropping on her, and even watching her sleep.

In the opinion of many readers, Jacob is a better choice for Bella than Edward. He has a friendlier, more positive personality than the vampire. He is also somewhat safer, acting most dangerous toward Edward. He is just as protective of Bella as Edward, willing to do anything for her. However, Jacob’s willingness to put aside anything for Bella causes him to rebel against his wolf pack, denying his responsibilities and coming across as childish.

Again, Edward and Jacob are both meant to be seen as desirable by female readers who relate to Bella as she struggles to choose between them. But neither of them are good role models for male readers: Edward is toxic, and Jacob is immature in his own obsession with Bella. These details can easily be considered symptoms of them being created by a female writer.

E.L. James supposedly based her book Fifty Shades of Grey on Edward Cullen and Bella Swan’s relationship. Christian Grey, then, is inspired by Edward. Although he is not a supernatural creature, Grey is dangerous: he identifies as a dominant, only capable of physical intimacy if he is in control and even causing pain to his lover.

However, unlike Edward, Grey is always polite, bearing some resemblance to the gentlemen of Austen and Bronte’s novels. He is even willing to make certain changes to himself for the sake of Anastasia, the romance’s leading female. He strives not to cause emotional or mental damage to Anastasia, although he does hurt her unintentionally by being too guarded and distant. James makes Grey into another Byronic hero, attractive but flawed.

Yet another example of a Byronic hero is Severus Snape from J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter franchise. Throughout the series, the Potions teacher at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry is almost as antagonistic toward Harry Potter as the Dark Lord Voldemort. He is cruel, creepy, and stuck-up – the last in particular being a trait associated with the path to the dark side in Rowling’s Wizarding World.

Meanwhile, Snape is undeniably good at what he does. He infamously found several shortcuts while studying Potions and even invented his own attack spell. The upsides of his stubborn attitude also include fierce commitment to the people he chooses to care about – like Dally Winston, he does care about people more than he lets on. The problem is that he has a very strange way of showing it.

Snape was in love with Lily Evans when they were students together. Lily ended up dating and marrying James Potter, one of the kids who bullied Snape. This gives Snape a strong resentment for James and results in very mixed feelings toward Harry, the boy who reminds Snape of both James and Lily. Snape is cruel to Harry in person but secretly protects him whenever he has the chance.

The argument is eventually made that all of Snape’s cruelest attributes are a performance: he acts evil to earn the trust of Dark Lord Voldemort while secretly working with Headmaster Dumbledore against the dark side. Altogether, Snape is one of the most controversial characters in recent memory. His negative characteristics are not quite as toxic as Edward Cullen, for example, but his positive actions may not be enough to erase those flaws.

The Mutants and the Mechanic

The comic book industry includes some notable female creators, and many of them create male characters to join a traditionally male-dominated world of superheroes and supervillains. In 1986, Louise Simonson created Apocalypse, who would become one of the most notorious supervillains in the X-Men franchise. In the story of Apocalypse, Simonson converted one of the very first X-Men characters, Warren “Angel” Worthington III, into a new character called Archangel. She also created Nathan “Cable” Summers and John Henry “Steel” Irons.

Apocalypse claims to be the first mutant, an evolved form of humanity in the Marvel multiverse, and is one of the most powerful mutants of all time. Consequently, he considers himself a god even among mutants. He repeatedly tries to establish mutant dominance, with himself as the world’s ultimate ruler, through human genocide. In spite of this, Apocalypse retains some noble, almost gentlemanly features: he respects certain superheroes as worthy opponents, and his actions seem more like carefully planned plots than temperamental abuses of power.

Warren Worthington was originally a member of the heroic X-men, but after he loses his naturally grown angel-like wings, he allows Apocalypse to replace them. The resulting transformation is traumatic for him. Even after he stops serving Apocalypse, Archangel is a bit darker than he was as Angel. In his early days, Angel was a cheerful, albeit hedonistic, rich kid and a responsible hero. Archangel, in contrast, sees himself as a monster and has been known to act the part.

Transitions like Angel’s happen frequently when a comic book character is taken over by a new writer. The fact that this transition was from male writers to a female writer may explain his change from cheerful to dark and brooding – under Simonson’s control, he pretty much becomes a Byronic anti-hero!

Nathan “Cable” Summers is another Byronic anti-hero from the X-Men franchise. A time traveler who grew up in the future, Cable is usually on a mission to prevent a tragedy, even if that means killing people along the way. He has no use for manners, having lived through apocalyptic scenarios where they were completely unnecessary. Louise Simonson and her collaborators reportedly meant for Cable to be the opposite of Professor X, the leader of the X-Men. While the Professor hopes to change the world subtly and slowly, Cable pursues goals aggressively, unhindered by fear of collateral damage – like a “real man,” some might say.

Another notable creation of Simonson’s is Steel, one of Superman’s associates. John Henry Irons, a mechanical genius inventor, designed weapons and was then wracked with guilt when he saw them being used so close to his home. This prompted him to become the armored superhero Steel. He continually feels an immense responsibility to protect people, and he is easily the most noble and decent character mentioned in this article so far.

The Measure of a Man

There is no indisputable method to determine the quality of a character or how good a writer is at creating characters. The question in this debate seems to be how realistic these female-written male characters are as opposed to the infamously unrealistic female characters created by male writers for the male gaze.

The easiest complaints about the realism of male characters are their exaggerated attractiveness and/or their lack of manners. The concern is that female writers create fantasy men, raising the expectations of female audiences too high, or uncivilized brutes, turning female audiences against real men altogether. Both of these types of characters create bad examples for male audiences to follow. In analyzing the realism of the characters mentioned here, we will see how well they hit the “sweet spot” between these extremes.

As the literary blog No Sweat Shakespeare points out, “in the world of Jane Austen’s novels,” which is effectively the same world as the setting of Bronte’s Jane Eyre, “masculinity is tied up with gentlemanliness… a man’s ability to attract a woman into marriage.” Over time, the definition of masculinity has become more fluid, although it could be argued that men, particularly fictional men, continue to have the same goal – wooing women and filling their societal role as boyfriends and husbands. Therefore, whichever features attract women remain a man’s most masculine traits.

Edward Rochester is overtly masculine in the best ways, securing the attention of multiple women and marrying not one but two of them. While some of his methods are not attractive when they are revealed, he eventually changes for the better. Fitzwilliam Darcy goes through an even greater journey of development, beginning his story unattractive to almost everyone and ending it “without doubt, the most attractive and masculine man of all” (No Sweat Shakespeare). Through his actions, he demonstrates all the admirable traits that matter to the woman he wants to marry, and so he serves his purpose perfectly. Both of these characters demonstrate their authors’ ability to write characters who develop for the better.

As previously noted, Dally Winston has no romantic arc in The Outsiders, so his masculinity is not measured by his ability to woo women. Instead, it is measured by his ability to get what he wants through bold, decisive action. As a functioning member of a street gang, he is independent, successfully separated from his toxic home life. Even his death demonstrates this. “…Dallas Winston wanted to be dead, and he always got what he wanted” (The Outsiders). He is not necessarily a good role model for male audiences, but he is not meant to be. Again, Hinton’s goal was to use Dally to teach her readers to imagine everyone complexly.

Dr. Victor Frankenstein marries his childhood friend Elizabeth Lavenza. Like Edward Rochester, Frankenstein hides his greatest shame and appears attractive while this secret remains concealed. After all, he is clearly driven, like Dally Winston. These traits make Frankenstein undeniably masculine, but that is not necessarily a good thing in this case.

On their wedding night, Frankenstein’s hidden shame strangles his wife to death – something the Monster warned Frankenstein would happen. If Frankenstein had told Elizabeth the truth about his work, she may have rejected him and thus survived. Regardless, marrying a woman after being told the Monster would come to ruin his wedding is rather irresponsible of the doctor. These details detract from Frankenstein’s character.

Frankenstein’s Monster never gets a chance to pursue romance because Frankenstein refuses to create a female counterpart for him. However, the Monster inherits a similar ambitious nature from his figurative father while showing no gentlemanly restraint. Shelley seems to be associating a primal urge toward violence with masculinity. Without a bride to compare him to, we cannot say for sure if a female would be more peaceful, although Frankenstein seems to believe the Bride would be just as dangerous as the original Monster.

Edward Cullen succeeds in getting a relationship with Bella Swan, making him more masculine than Jacob Black by the classical Austen-inspired definition. However, winning Bella’s love is not Edward’s initial goal. He makes it clear that Bella should stay away from him. His stalker-like behavior demonstrates how dangerous he is, but his self-awareness of this fact demonstrates his maturity. This is another advantage he has over Jacob. Still, Edward and Bella end up getting together, suggesting that Meyer sacrificed a good example for a “happy ending.”

Christian Grey’s politeness in the midst of wooing Anastasia’s affections at first makes him a gentleman similar to Darcy and Rochester. However, he does not finish E.L. James’ first book in a relationship with Anastasia because he is keeping things from her. The fact that Anastasia recognizes this as a significant problem suggests that James also recognizes it. Grey’s character development is intentionally left unfinished.

In J.K. Rowling’s Wizarding World, where a diminutive elf can move a large cake through the air by force of will, intelligence is strength. Therefore, Severus Snape’s talent at magic contributes to his masculinity, as does his ambition. By the standards of Austen, his snobbish rudeness and his failure to marry the woman he loves may detract from his gentlemanliness, but for this debate, they do not hurt him. Snape is a quality, realistic character, even if readers cannot agree whether he is a good guy or a bad guy.

Louise Simonson’s entries in this debate are all undeniably ambitious. As previously noted, Apocalypse retains a gentlemanly nature despite his god complex. Steel has the decency to take responsibility for his ambitions when they get out of hand, unlike Frankenstein. Archangel and Cable may be more anti-hero than hero, but like Severus Snape, they still seem like quality characters.

Based on this list of well-known characters, there seems to be a trend of female-written male characters discarding gentlemanly manners over time. As women’s standards have shifted, the standards of masculinity have changed. For those who like decent men, there are the classics like Darcy and heroes like Steel. For those who prefer a little darkness, there are Byronic heroes like Rochester, Dally Winston, and Snape. And if you ever want an example of what not to do, there’s Frankenstein the mad scientist and Edward the vampire.

In the end, ironically, female audiences are more likely to have a problem with male characters leveraging their masculinity just to get girls, as if they’re prizes to be won. Combined with the way women are portrayed, men both fictional and non-fictional can do better.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I wasn’t sure how to react when you wrote that Dally committed “suicide by cop”, so I just laughed.

Interesting. I love the different examples you mentioned – did not expect to see Dally (or any references to The Outsiders whatsoever) in here. Also, we’ll never get tired of bashing on Twilight, will we?

Lots of varied examples, very nice!

I think it’s also interesting to consider genre here – the *purpose* of these male characters in each story (as romantic interests, warnings, or villains) plays into our expectations from them. Snape is never intended to be read as a romantic lead the way Darcy is, and so the way their masculinity is portrayed and perceived (through the lens of our POV characters Harry and Elizabeth) will be inherently different.

I tried to read Twillight but had to give up – I couldn’t get over the bad prose. I watched the movies however and it’s clear to me why there are popular. Mayer tapped into something that most teenage girl-targeted movies/books completely miss out.

Whilst there are some great female writers they is no female Shakespeare or Conrad.

Certainly not because women have been excluded from artistic endeavours.

Sadly, women in the time of Shakespeare and Conrad weren’t ‘allowed’ by society to be a writer or painter.

And in a lot of cases, neither were poor people.

An interesting thesis, and pretty well presented. Thanks for this, Noah.

I will admit to having read far more many male writers than female, and probably still continue to do so.

I will also admit that in general, women seem to do male characters better than men write women.

But I don’t believe they are perfect depictions either. More and more it seems as though neither sex can write the other really well (even though women generally make a better fist of it). What hope is there for trans people say, unless in novels written by trans people?

I dont’ want this to be depressing and pessimistic about the future of the novel.

I have no doubt at all that women are better than men at writing both genders. I recently tried to think of men who successfully wrote women characters, and could only come up with a few, but I thought of many women who successfully wrote male characters.

I think this could be partly to do with disadvantages imposed on the male perspective from an early age – girls are often encouraged to read both “boys’ books” and “girls’ books”, whereas a boy would probably be actively discouraged from reading a “girls’ book.”

(I’m a woman myself, by the way.)

Show me one man who writes, or wrote, as well as Muriel Spark.

The sorry truth is that if a person is adult and male, he is discouraged from noticing what’s going on with and inside the women/children around him. While for adults who are female, paying attention to what is going on with and inside nearby men is encouraged and occasionally lifesaving.

There are only two kinds of writing. Good writing. And bad writing.

Jane Austen. Enough said and I’m a bloke.

Both men and women have written good novels over time but have different perspectives which mean that those by one gender may not be to everyone’s taste.

I do not think gender has any bearing in the quality of the writing of the characters. The fact that lot of male writers are overrated, and women could not get away with writing such shitty books is another discussion altogether.

Give us an example…

Philip Roth has been publishing tosh for decades and look how revered he is, Saturday by Ian McEwen is career destroying but still managed to get some decent review and his reputation is not dented one bit, Franzen’s Freedom is absolute shit and it’s hailed as this great American novel and the list goes on and on, and then you have people like Donna Tart if she does not get it absolutely pitch perfect the only thing she gets is condescending reviews. Enough of examples for you?

Oh come on female writers have got away with a whole genre of shitty books known as romantic fiction. Because it sells, not because it’s any good.

There is so much diversity in the way men and women write their characters as to make all generalisation simply silly.

A lot of women novelists could do with a better understanding of men.

Not to say there aren’t a great many hugely talented women writers, but I find their male characters sometimes tend toward simple personification of either patriarchal authority, sexual adventure, or boring mediocrity. And the men often seem to be judged to a large extent on their appeal (or lack thereof) as potential lovers.

Of course a lot of these writers are still very talented, and write very enjoyable books. But they often don’t seem to fully understand certain aspects of the male identity (such as, for instance, the ceaseless pressure to be successful and its impact on the life choices, attitudes, and even physical mannerisms of men).

I’ve read brilliant male and female writers. And I’ve read awful male and female writers.

Exactly. There is no ‘set’ way of writing or a particular genre that either gender specialises in. For example the very best two fantasy writers I have read are women- Ursula Le Guin and Tanith Lee. But I think there are great male fantasy writers too.

Can we enjoy and appreciate novelists and their work without first inspecting their genitalia?

Yes, but it would be great if writing was just assessed on its quality but that’s not happening.

Great article. But my take on it is that good art – whether visual, literary or musical – shouldn’t be about gender, race or genre. It should be judged on it’s own merits. After all, brilliance can come from anywhere.

This. The only time gender comes into play is the sad fact that women artists and writers have historically been suppressed and unable to express themselves. I hope that no longer applies.

I’m going to generate a backlash here but I find female authors boring and their work lacks literary merit.

I made a concerted effort to read more female writes so I tried (and gagged) with Kamila Shamsie’s Burnt Shadows. A book that tries to justify September 11 by linking it to Hiroshima. When doing my degree I wrote a dissertation on Margaret Atwood’s Alias Grace and Toni Morrison’s Beloved. Atwood is so clever she is contrived; Grace was involved in a true-life double murder but she’s female and sexualised by the patriarchal society. Oh I see now! Morrison does recount a horrifying incident of a slave murdering her infant daughter rather than be returned to captivity. But characters emerge out of nowhere to the point the plot breaks down. Then I tried Beryl Bainbridge and the verbose Doris Lessing. I will try to approach female writers with an open mind. I did enjoy Elizabeth Taylor’s Mrs. Palfrey at the Claremont.

Nice work! As a Snape fan, thanks for including him. I don’t like my men quite as dark as Snape, but I enjoy a decent man with a bit of an edge.

Sounds to me like you need to read something like the “How to Train Your Dragon” book series or the “Chrestomanci” series.

Books like those of Ms Meyer lay bare what some sick women want out of relationships, the opportunity to tame a asshole of a man into a domestic pet and then enjoy the quilty pleasure of being “ravished” by him. This same fantasy has been repeatedly described by female authors like Jane Austen of the Brönte Sisters, if in a more sedate manner, and it’s stock in trade for any Harlequin novel. It doesn’t suprise me that Fifty shades of Grey was fan fiction of Twilight, it’s just the next step in the process.

Except that in twilight she becomes as powerful and ‘wild’ as he is at the end.

I’m 25, and first read the Twilight books when I was 22, so am probably a little too old for the target market. But I loved them. It just seems far too easy for people – usually people who have never read the books and have no intention of doing so – to mock them. Having spent my teenage years in genuinely abusive relationships, and having just broken up with an alcoholic, drug addicted ex after he attacked me whilst high and tried to rape me, I read Twilight for the escapism. The books’ idealised depiction of love and relationships seemed surreal, archaic – and, to me, irresistible. I started identifying as a feminist around that time, when I started reading certain texts for essays at uni. Discovering feminist writing felt like walking into a room of kind, strong, fearless women – like being hugged and reassured that things weren’t my fault – that things could be okay. Oddly, the time I spent on my own immersed in Twilight – reading something solely because it was enjoyable, because it was romantic and escapist, a teenage fantasy – felt like part of that journey. So, yeah – I find it irritating when people are so dismissive about Stephenie Meyer’s work.

I have read them all, and seen all the films. I’m a writer and I read 5-7 books a weeks. I actually think that I am in an excellent position to mock them.

The whole teenage girl falling in love with a vampire has always struck me as an odd romantic notion, but it can work well if written well, but that’s really not the case here. They’re not very well written, the characters are barely 1 dimensional and the universe she created had such potential but it’s all squandered for the sake of telling the mopiest and misconceived love story of our time

But hey, if you like them, no one can take that away from you. So don’t let it irritate you. I’m sure it doesn’t bother Meyer as she sits in a house made of money.

Tbh, I can see why many people think they’re not that great. It’s not really people who have read the books and formed their own opinion that irritate me, more just those who seem to jump on the bandwagon and dislike them because it’s seen as the done thing to do… I guess I just feel compelled to defend things that I enjoy, rather than deny the fact they gave me pleasure in the first place. I think people get very frightened of being judged when they admit to enjoying something that’s widely viewed as awful… But then again, I guess people have every right to slate a work of art that they genuinely think is poor.

Thank you for this article. It gives voice — of course you’ll get trolls, so Welcome to Hell! — to much of what many authors I know in my circles who are female have said forever.

Some of my favourite writers are women, Rose Tremain, Marilynne Robinson, Pat Barker, etc. Some are also men. Damn! i like writing by both.

It comes down to the individual regardless of gender which is what we should all agree on.

I don’t care about who writes the book if it’s good. I enjoyed Ann Rice’s vampire chronicles as much as Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes.

This reminds me Jack Nicholson’s character in the comedy ‘As good as it gets’; he played a writer who was asked ‘How do you write women so well?’ He replied with his usual snarly smile, ‘I think of a man, then I remove all reason and logic’.

No, the Twilight books are not great literature. But they have been Harry Potter for teenaged girls. They have a blank heroine with whom the reader can identify, can feel ‘in their place’ and yes, todays sexual culture faced by young girls and women is one of low respect and intense pressure. So having a male love interest who actively refuses to give in to desire and advocates chastity and committment is attractive, like it or not.

Neither male nor female are superior to each other as writers, they are simply approaching from a different personal condition.

It’s very easy to criticize Meyer’s writing, makes us feel good about ourselves. It’s much less comfortable to wonder why her books are like crack to so many girls of all ages – it tells us things about our society we would maybe rather ignore.

That in some respects, popular culture has gone backwards over the last 30 years?

More female writers means more female characters, in all their variety, and I’m all for that. 🙂

There have been some superb women writers (Austen, Eliot, Woolf, Bowen) but could a woman have written the plays of Shakespeare or the novels of Tolstoy, Dickens, Conrad or Balzac. Probably not.

You haven’t given any reason why women couldn’t have written those works.

The idea that women are somehow any more keyed into an understanding of human nature, and thus produce more ‘authentic characters,’ is a nonsense assertion which helps no-one.

Women dominate literary fiction as readers. Time to stop fighting the wars of the past. When it comes to fiction, women won. Today, reading by males drops off a cliff in their teen years. Reading fiction is well on its way to becoming a gendered activity.

A rewarding area to explore is gendered reading, and how publishers and female writers use the available research. How it impacts on what gets written and published.

It seems like the vast majority of current YA fiction is written by women and the majority of the main characters are male.

I’ve read plenty from both sides and I can say I enjoy the different perspective women authors have on male characters (and things in general). There’s only so many actual stories and most everything is repetitious. A fresh perspective is enjoyable.

To be honest though, I have never thought that female authors really understand men.

Although I’m unfamiliar with the comic book characters, I appreciated your article and the interesting juxtaposition of Edward, Rochester, Darcy, Dally and Grey. I think you could’ve gone into more depth with Jacob for the reason that you didn’t mention the scene where he kisses Bella by force and how he continues to be romanticized despite this with him being all but promised Bella’s daughter’s hand in marriage.

I also believe there’s a difference in writing complex, flawed characters and writing for the female gaze. When it’s the male gaze, women are weak damsels in distress, so I think that having men being perceived as ridiculously strong, dangerous and overpoweringly dominant like Christian Grey and Edward Cullen are solid examples of the problematic way in which some women portray masculinity. The other books you mentioned I personally find have less of a message about dissing the male gender when considering their overarching themes.

However, I wouldn’t go so far as to include Frankenstein, the first science fiction novel and one of the best Gothic novels of all time and single out the fact that Shelley was a woman. She had to deal with this while she was alive with people believing Percy wrote her masterpiece, so why feel the need to bring up her sex today? Frankenstein was about more than masculinity– it was a work of art about (according to my interpretation of it, whereas some might see it as about fatherhood) playing God. Something that stood out to me was the line: “It seems worth noting that the Monster is male as well, and although he develops eloquence and strong argument skills, he is driven by a primal urge toward vengeance against those who have mistreated him. Shelley seems to argue that this destructive behavior is a natural instinct of life itself, at least for male life.” This, I believe, is a little far BUT in order to properly write about gender, ruffling a few feathers and being opinionated is a must. So while I don’t agree with you entirely, I will say that I admire the amount of thought and time it took for you to write this up.

Fascinating article about a topic I have often pondered! I have heard the argument that women written by male authors are inaccurate, but rarely have I read the reverse point. I love how the article began with the example of Frankenstein, in which Shelley depicted Victor as an arrogant and irresponsible character. I read the classic last semester and considered similar claims. Great read!

Of course not all male characters written by female authors are fully realized depictions of masculinity. But one of the primary reasons that male authors are criticized for their depictions of female character more female authors are for writing males and, similarly, why white authors authors depicting POC characters, CisHet authors depicting LGBTQIA characters, abled writers depicting disabled characters, and generally any author from a dominant culture depicting a character who has been marginalized or othered by that dominant culture, is criticized is that authors from the dominant culture are never required to consider the perspective of anyone not included in that dominant culture, whereas the very survival of anyone outside of that centered culture requires fluency in the discourse of dominance. Those on the margins can always see the center far more clearly the those in the center can see the margins.

I think characters are generally there to serve a purpose – especially when they do not have primary roles as empathetic figures in the story, writers can see characters as progenitors or plot or conflict, and not as 3-dimensional humans. Creating a 3-dimensional character takes a lot of time and energy and may not be necessary in all circumstances. I think this may be the reason for these derivative male characters, regardless of the gender of the writer.

While you’re probably right about some of that, Edward Cullen and Rochester and Christian Grey are the love interests of their books, and Victor Frankenstein is the narrator of his book. These are the opposite of derivative characters. If they are not well-defined, that’s a valid criticism. If they’re bad role models for potential male audiences, that’s a valid criticism.

I would disagree with the idea that masculinity is defined by what women find romantically appealing. Many of the characters listed go against traditional modes of masculinity (being too emotional or too effeminate). Masculinity is defined largely by male peers.

I find your choices for examples interesting. Jane Eyre and Frankenstein are both Gothic novels meant to comment on the Patriarchal society and colonialism which influences the way the men are written. Twilight, it could be argued, is just poorly written with Bella being a rather flat, shallow woman character whose choices shouldn’t reflect normal females. This probably also applies to 50 Shades of Grey, though I could never bring myself to read it. There are plenty of talented female writers who have more complex, better written male characters. It is also interesting that you criticize the authors for following trends on what makes a man attractive to a woman when some of your choices are romances. Of course a romance author is going to make the main male character attractive! That is the point of romances.

Some really great examples here, great read!

So what are examples of the ‘good’ or ‘authentic’ male characters written by female authors

I love these examples! Honestly, I think what it boils down to is the human tendency to trust people (or look past their wrongdoings or red flags) if we perceive them as attractive. If Edward Cullen wasn’t hot, Bella would have thought he was a creep from the get-go.

I think your discussion of Frankenstein not being appointed a female counterpart is very intriguing. It raises a discussion on the softening of male characters (who are written by women) when a female counterpart is involved. The male characters once violent and ‘masculine’ nature is partly distinguished, only returning when their significant other is in danger and in need of protecting.

I appreciate you bringing attention to the gendered lenses writers (consciously or unconsciously) implement. I think drawing attention to these tropes and gendered roles can help us analyze how certain expectations come attached to the gender of a character, and ultimately, how have these roles come to reflect society, or vise versa. I don’t think writers are done exploring these tropes just yet, but I think it really pays to be mindful of them and how our preconceived notions can be influencing one’s writing for better or worse.

I found this to be a very interesting and insightful read! I don’t usually consider Twilight to be relatively Austen-esque, though I love the comparison you were able to draw between the masculine archetypes presented by both worlds. One thing I would love to know more about, and may explore myself after reading this, is how these masculine tropes translate in queer or queer-coded relationships. Do these exist in the same spaces, or are they treated separately (or, in the case of Twilight and most works mentioned, not treated at all)? Once again, great article!

Writing is nothing short of difficult. As writers, we can not take ourselves out of our works. That includes; implicate biases, preferred types, and imagination.

This piece brings to light the differences between writers and how we take into account the gender of those writing. Since women writers especially in the early ages were silenced, we have sparse collections.

I feel that putting these gendered types in how we analyze writing makes it increasingly difficult to change how we write.

Writing is writing.

I did really enjoy this article, it made me think about how I view characters and authors in what I read.

When I first saw the title, “Dreamboats or Brutes”, my mind initially snapped to the idea of the Angel/Whore split discussed by Margaret Atwood in her essay “Spotty-Handed Villainesses”, the notion being that traditional portrayals of femininity are either perfect and pure of heart, or evil monsters/masterminds. Of course it may be prudent to consider how many of these female characters were written by male authors or playwrights.

However, your article approaches males characters as written by women in a very different light than I was expecting, identifying both harshness and more positive attributes alongside one another. I wonder to what extent the darkness is inseparable from the good? If a man with no goodness is more a monster than a man, then what’s a man without darkness?

Short answer: a man without darkness would probably be too boring to be attractive to female readers.

Giving a character flaws as well as good qualities adds dimension to him. Darkness is inseparable from the good because real people are flawed.

I loved this article. I was impressed with The Outsiders reference, I loved that novel. As a woman and as a writer, I design characters in what I would want in an unattainable partner. Part of the fantasy I guess!

This is a really interesting article! I’m not personally a fan of the “brooding mysterious guy” characters, but I think a lot of female writers like to explore this archetype because these characters exist outside of reality. In the real world, the patriarchy puts women at a disadvantage, and bad men are dangerous to women. But the female writer holds all the power to shape the fictional bad boy into whatever she wants him to be. Since she’s the one in charge, she can give him a moral code or manners that a real bad boy wouldn’t have. In a way, it allows women to reclaim power in a patriarchy.

That said, I don’t think these characters should be romanticized as examples of what women should look for in partners. It’s ok to use literature as a safe way to explore these dynamics, and I do understand why some women find them appealing. But we must maintain a strong line between fantasy and reality.

I love the premise of the article. I have always found that it is common for authors writing from the perspective of a gender that they do not identify with often backfires. I had never actually thought of this in the context of women writing male characters, because I am usually focused on the overtly sexual way in which men usually write female characters. I had never considered that this sexualization is two-fold.

I definitely think it depends on the genre and what the function of the male hero is in the story. Let’s face it, male characters in romance novels written by women are idealised versions of masculinity; what the heterosexual female reader wants in her male partner. But often in these novels, the male hero isn’t just sexualised, he’s given attractive emotional and behavioural qualities too. The most common complaints I see about men writing women are more about how some men write women’s bodies/anatomy, or in some cases reduce the women to her physical/sexual being. I think there’s a difference between THAT and just writing a character that we think behaves a little unrealistically which I am more inclined to forgive.

Men and women are entirely different creatures. They think, feel, act, and love differently. Unless one is VERY familiar with how the mind of the opposite sex works, it would be unrealistic to expect them to write characters of the opposite sex accurately.

It’s Charles Bingley, not John. Easily googled.

I’m not sure if I agree with the idea that because the male characters aren’t good role models for boys, they’re poorly written. Isn’t the point that they are complex, multi-dimensional people with both good and bad traits. Which seems to be true of all the male characters you mention.

It is one-dimensional stereotypes that I take issue with, no matter the character/author gender.

Snap every much is reminiscent of Loki in Norse Mythology, with perhaps broadly similar outcomes in his double-dealing.

In any case, women write men based on their experience.

Are you worried (at all) that the broader message here seems to be ‘just do better’… it feels a little like throwing rocks at a glass house. I’d love to read more about your recommendations for solutions as a follow on. What you’d prefer to see in terms of characters representation might help turn criticism into critique

Interesting article! I think you raise some good points- female writers likely fall into similar traps as male writers do sometimes with making the opposite sex too stereotypical or fake. However, I think some of the examples you use show how female writers have created some complex male characters successfully. Snape, for example, is a complex character who avoids being placed into a box. Rochester is also rather complex. I think an interesting side question is how do these stereotypes affect men and women with dating? But at the same time, sometimes you just like reading a good story with heroic characters, rather than realistic ones. Twilight gets criticized a lot, but a juicy love triangle with attractive characters is a lot of fun.

Aside from biological essentialism, what counts as “manly” or “womanly” changes across cultures and across time. This applies to authors as well as to characters. What a female writer will write about a character in the context of early 15th century French aristocratic circles (de Pizan) differs from what a female writer will write about characters in a post #MeToo upper-middle class American context. To sweepingly generalize about “women” (or “men”) as writers across time and space brutally ignores history and culture to such a degree that the category (“female author/male author”) itself becomes useless.

Perhaps the problem is more these writers’ ability to craft convincing and realistic characters and not the sensation of mischaracterizing men in general. But when writing about someone who is not yourself or who you can’t necessarily relate to, there will always be holes in the story.

This article is quite controversial. However, I believe that both male and female perspectives in fictional writing will always have an underlying theme between what they are attracted to and what is considered attractive in popular culture to get a response from the targeting audience.

I find this article insightful; Both men and women write with an idealized sense of the other.

Or a very much not idealized sense, sometimes

You brought in some really interesting examples, and it’s great to see you explore both a wide historical span and spectrum of genre. A lot has already been said about how “good”/”bad”, or generally insightful writing is informed less by gender and more so by ability – either to write as a whole or to look outside one’s self long enough to be able to flesh out any sort of character thoughtfully and articulately.

I’m curious to see what you’d make of, let’s say, women authors who write their female characters in poor taste. There’s also a lot of variety in that area, we could look at anyone from Emily Brontë to Gillian Flynn. An argument could be in favour or against them either way, and this duality is also perhaps present in your line of thinking – that we as readers will always be struggling to determine who can provide an authorial voice on matters that may not immediately or personally concern them.

A fascinating take on female gaze!