Is Mental Illness an Over-Explored topic in Indie Games?

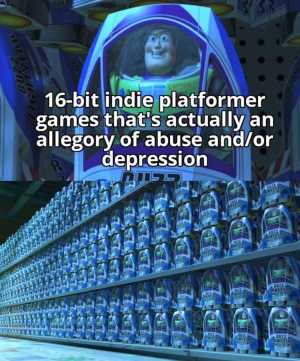

There’s a meme that’s been doing the rounds in online spaces for a little while now. A few memes, really, but they’re all variations on the same theme. The joke is that there are too many indie games that are actually an allegory for depression, and that everywhere you look are quirky indie rpgs (possibly also done in pixel art) that focus on the exact same topic: mental health. And it’s not always just a joke, but for some people a real concern and complaint. Some legitimately believe there are far too many indie games about depression.

There certainly are a number of popular indie games that explore the topic of mental health. But is the topic so well-done that it’s become over-explored, and worthy of such cynical memes and complaints? Are games on this topic just retreading the same old ground, or do they have new insight to give on such an important subject?

What parts of Mental Health are Explored: Stories

When it comes to these jokes, the games typically brought up are Celeste, OMORI, Yume Nikki, and Lisa the Painful. They are not the only ones mentioned in these jokes, but they are certainly the most common, and generally the most well-known and popular. And yes, each of these games do explore mental health. Celeste focuses on a girl with depression named Madeline, who climbs a mountain and comes face to face with the personification of her inner doubts and bad side. OMORI is about a teenage boy, who (after the death of his sister) becomes a recluse (a ‘hikikomori’, hence the title) and delves into fantasies instead of engaging with real life. Lisa the Painful involves a middle-aged man journeying across a post-apocalyptic wasteland to find his adopted daughter, while dealing with his past and a drug addiction. Yume Nikki (‘Dream Diary’ in Japanese) focuses on a young girl travelling through multiple surreal landscapes in her dreams.

These games do have some similarities in their portrayal and exploration of mental illness. Both Celeste and OMORI feature a ‘dark’ version of the main character, who represents some aspect of themselves or their depression. Both OMORI and Yume Nikki involve reclusive children in a dream world, and have themes of suicide. But there’s a lot of difference to be found in all the titles mentioned as well.

Even while they all explore the topic of mental health, and depression in particular, each of these games have slightly different takes on the topic and different focuses. Lisa the Painful is especially different from the others, as it focuses on drug addiction and withdrawal – something none of the others discuss.

But even with these similarities, each work is still very different. Celeste and OMORI both have ‘dark’ versions of their main character, but they are executed differently. In Celeste, ‘Badeline’ (the dark version of Madeline, the main character) initially fights against the player character, putting her down and telling her that she’s not good enough to climb the mountain. However, over the course of the story Madeline learns to work with this personification of her worries, comforting her instead of fighting against her. The story is about learning to love yourself, including and despite your flaws. In OMORI, meanwhile, the player character Sunny fights directly against this dark version of himself. Here, the character is separated into his ‘real’ self (‘Sunny’) and the unreal version of himself that is found in the dream world (‘Omori’). This fight involves a struggle to defeat his depression, to leave the dream world behind and for Sunny to live as himself rather than as this idealized ‘Omori’. While the narrative trope of a ‘dark self’ is present in both of these games, this different execution means that a viewer will have a very different experience, and draw different conclusions from them.

Similarly, both OMORI and Yume Nikki involve a reclusive child journeying in their dreams instead of interacting with the real world, but these ideas are explored in very different ways. In OMORI, this dream world is a beautiful one for the most part. The main character’s childhood friends and sister love and support him, and they all go on fun adventures and play together. However, Sunny is forced to interact with the real world once more when his former friends visit him. It can be seen how in the time that he has not left his house, these versions of his friends in the dream world have become inaccurate caricatures. We begin to see how false this dream world is. In some parts, it is idealized and saccharine, and in others it is nightmarish where Sunny’s fears and doubts seep in. The story is a call to leave this dream world and interact with the real world, as enticing as a dream may be. But in Yume Nikki, the dream world is very different. While some of the locations are nice to look at, they are all surreal, and many are rather unsettling or scary. In OMORI, the horror elements are scattered through the ‘nicer’ sections, and become more apparent over time. This difference gives the two games very different feelings. In addition, the ways that the two games’ stories end mean that their portrayal of mental illness, and their implications, are completely different. In OMORI, there are multiple different endings. It is possible for Sunny to stay forever in this dream world, or to leave it and reconcile with his old friends, to confront his internal issues instead of covering them over. This story indicates that it is possible to overcome elements of one’s mental health issue, to recover, but it is also possible to not recover. Meanwhile, Yume Nikki only has one ending, and it is the player character committing suicide by jumping from the balcony of her apartment. Its portrayal of mental health issues is, as such, much less hopeful.

To say that each of these games are the same simply because they all cover the same topic of mental health is inaccurate, and ignores the stories, nuances, and implications of each game. Outside of these four games mentioned, it seems to be much the same. While there are certainly games that overlap, the individuality of mental health issues and experiences mean that they are not identical.

How Mental Health is Explored: Gameplay

Another odd part of these complaints about the similarities of these games is that they tend to ignore the obvious differences in these games. But beyond the story similarities and the fact that pixel art is not uncommon there is a lot of variation – most importantly, in game play. Yes, all of these games discuss mental health, and the examples here are even all pixel art. But Celeste is a challenging platformer, while OMORI is a party RPG with puzzle elements. Lisa the Painful is also an RPG, but with very different mechanics – for example, in OMORI you play the entire game with the same four party members, but in Lisa there are many more potential members to choose from. Yume Nikki is an exploration game, with no combat or dialogue.

Even with the similarities in the topics and stories that these games explore, the mechanics mean that all of these games feel like completely different experiences to actually play. In addition, in each of these cases the mechanics feed into the game’s message about mental health.

Celeste, as mentioned, is an extremely difficult game. Platforming is precise and fast-paced, and each area introduces new gameplay elements to learn. Any new player is likely to die a lot playing this game. This separates Celeste from the other games on this list, as none of the other games are as physically difficult to play – to say that playing Celeste is identical to playing OMORI due to the subject matter of depression would be to ignore the very genre of Celeste. And this mechanical difference doesn’t just separate it on a physical level, but on a story and meaning level. Celeste is about Madeline’s struggles, both to climb the mountain and to deal with her mental health. By making the game a struggle to play, the player empathizes with her difficulties, and shares in both her failures and her successes. Having the game be so difficult means that the final triumph of reaching the mountain’s summit feels amazing, both on a story level (watching Madeline reconcile with Badeline and overcome her issues), and on a gameplay level (having all your platforming skills acknowledged and rewarded).

Similarly, the mechanics of each of the games mentioned here are different, making them all very different experiences to play. Their mechanical differences also add certain elements of nuance or meaning to the story or atmosphere in the game. In Lisa, the player can choose to have certain characters, including the protagonist, take a drug called ‘Joy’ to make them more powerful in battle. However, not using it can cause withdrawals that effect gameplay in a negative way. This mechanical use of drug taking invites the player to consider real-life drug use in a rather different light. While real-life drug addicts are unlikely to be in the scenarios shown in this game, these mechanics do serve to show how necessary drug-taking can feel to one addicted to them, especially when there are severe withdrawal symptoms. It invites sympathy for drug addicts. Meanwhile, in OMORI’s battle system, different emotions can cause different effects. They can make certain attacks stronger, or effect a battle’s rewards. Certain characters generally use one emotion in particular (as they have a particular move that responds well to a certain emotion), and this impression is emphasized by the in-game guide to using emotion mechanics. This means that each character is associated with that emotion, changing how the player views them. In Yume Nikki, some of the puzzles are strange, or the answer is not immediately logical, which adds to the impression of the dream worlds as surreal.

The mechanics used in a game can drastically change how a player views and absorbs the story and message of a game. While games focused on mental health may have similar stories and topics when viewed in isolation, differences in mechanics can mean that they, in practicality, feel very different to play.

The Numbers

The memes about indie games focusing on mental health all imply there are a huge influx of games about this topic. Some even take it a step further and imply the market is flooded with specifically pixel art indie RPGs which are about depression. But the truth is, there aren’t as many as they imply. As mentioned, the four games mentioned in this article (Celeste, OMORI, Lisa the Painful, and Yume Nikki) are generally the ones that crop up in these memes. The fact that all four of them are pixel art also serves to imply a similarity. Outside of them, however, it’s clear how few indie games about individual struggles mental health there really are, especially when it comes to the really popular indie games. Probing Google for recommendations on indie games about mental health generally shows the same 20 or so games repeating across lists from different gaming websites – apart from those four, it’s mostly Fran Bow, Night in the Woods, Depression Quest, and Actual Sunlight. None of these games, funnily enough, are pixel art. So that part of the meme is certainly wrong.

That’s not to say there aren’t any other indie games about mental health. There are a lot, and yes, some do tread similar ground or have similar gameplay. But the majority aren’t anywhere near as popular as something like Celeste is, which won a number of awards (including the ‘Best Independent Game’ award at the Game Awards 2018) and sold over a million copies by the end of 2019. That’s not something the vast majority of indie games can say, let alone specifically those about mental health. In addition, the games mentioned both in this article and in these memes are from very different times – the oldest (Yume Nikki) is from 2004, while the newest (OMORI) is from 2020. It’s not as though they were all released at once, flooding the market at the same time. As such, a fatigue from ‘too many’ indie games on the topic feels strange, unless you’re going out of your way to only play games about mental health. And it’s not as though mental health is the only popular topic in indie games, either. Trends and popular topics in indie games come and go, and having multiple games with similar topics isn’t particularly unusual. To be derisive about the volume of games about mental health is to ignore the fact that media is always building on what came before it, discussing and expanding on the same topics.

In addition, while sympathetic portrayals of mental illness may be more common in indie video games, they are not as common in more mainstream video games. One study monitoring the fifty highest-selling video games in each year from 2011-2013 found that 69% of mentally ill characters found in these games were homicidal maniacs, and the majority of mentally ill characters depicted in games were shown in a negative light. Similarly, another 2019 study focusing on games present on online gaming retailer Steam found that of games focusing or discussing mental health, 97% of those reviewed involved negative portrayals of mentally ill people and stereotypes. This included games where mentally ill people were violent and unpredictable, horror games where mental illness and supernatural elements were intertwined, and games where mental asylums are used as scary settings. While these studies are not completely comprehensive, they do illustrate a trend in media. While it may seem to some like there are a lot of indie games featuring allegories for depression or anxiety in sympathetic ways, there are far more that are much less sympathetic. Even if the memes were accurate, would having more games discussing mental health in a positive or realistic way really be such a bad thing?

In addition, there are many different types of mental health issues. While there may be a number of games that deal with, say, grief and depression, there are many mental health conditions that aren’t as well-explored. Also, each person’s experience with mental health issues is different and personal, and there are many stories we have yet to see in games. There’s still plenty of room for more stories exploring mental health.

While accurate and sympathetic representation of mental illness is on the rise, it’s still not where it could be, and many mentally ill people are still unsatisfied. As such, it’s not surprising that many people who have struggled with mental illness want to tell authentic stories – their stories – and help fight this stigma.

There are a number of indie games focusing on mental health, but in the wider medium of video games it’s not that many, and there’s a lot of nuance to be found in such a personal topic. In addition, the games that do focus on this topic cover a range of perspectives, stories, and mechanics, with more differences than similarities.

With so much progress and positive representations still to be made, and so many areas of mental health still largely unrepresented in indie games, mental health definitely isn’t an over-explored topic.

Works Cited

- Phillip. (2018). EarthBound-Inspired Indie Game About Depression. Know Your Meme. https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/earthbound-inspired-indie-game-about-depression

- Shapiro, S., Rotter, M. (2016). Graphic Depictions: Portrayals of Mental Illness in Video Games. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 61(6), 1592-1595. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1556-4029.13214

- Ferrari, M., McIlwaine, S., Jordan, G., Shah, J. L., Lal, S. (2019). Gaming With Stigma: Analysis of Messages About Mental Illnesses in Video Games. JMIR Mental Health, 6(5). https://www.proquest.com/docview/2511388077

- Wikipedia. Lisa: The Painful. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lisa:_The_Painful

- Wikipedia. Yume Nikki. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yume_Nikki

- Wikipedia. Omori. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Omori_(video_game)

- Wikipedia. Celeste. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celeste_(video_game)

What do you think? Leave a comment.

It’s so important to address mental illness, no matter whether it is in an indie game or mainstream game. This article is very well written, and makes a very strong agrument.

To me, it is all about Persona 4. The dark parts of you that you don’t want to see or acknowledge… But in accepting that part of you, you grow stronger! Now I feel like fireing up my ps2 and playing P4… But I need sleep…

Thank you for presenting this article in a easy-to-digest way, so that both gamers and non-gamers can understand. I was able to share this with my non-gaming parents to help explain what sort of stuff I go through with my depression and anxiety.

Ack, Celeste. After this fight, when I was climbing the summit, I felt confident. The game made me feel that I was unstoppable. Even when I failed, I knew I could eventually get it. This game is very fun.

Another game that (either deliberately or inadvertently) comments on mental illness — specifically depression — and gives a very true-to-life depiction in its subtext is Telltale’s ‘Tales from the Borderlands’ with the ghost of Handsome Jack, implanted in Ryhs’ cybernetics, acting as a representation of the illness itself, of raw negativity. I don’t know if you’ve ever played it, but I would be eager to hear your thoughts.

I personally deal with panic attacks, so i can relate to Madeleine a lot in that aspect. I loved Celeste so much, and it helped me understand my own emotions and myself better, and seeing it come to a close with the fantastic Chapter 9 (Farewell) has been hard.

In Lisa the painful, I love how all of the party members you acquire in the game aren’t people who are destined for greatness or part of some prophecy. They’re just random dudes that Brad happens upon throughout your journey. Some just want to hang out with Brad, but others want to get a shot at Buddy, or are even travelling with him because he is holding someone or something ransom. Just because they’re in your party doesn’t mean they like you.

I personally really like Brad as a character too, he was just trying to do the right thing. He just wasn’t able to do it good enough. He did honestly care though, which I can whole-heartedly respect. Brad’s a homie ,a drugged up homie, but a homie nonetheless.

For all Brad’s faults, for how much he’s a product of his father, it’s hard for me to say he did a whole lot wrong by his own hand. The apocalypse is no place to raise a child. His ultimate failure was his assumption, fueled by Joy, granted, that his Father couldn’t change, that his father wasn’t hurt as deeply as he was, that his father didn’t also want redemption. In the end, Buddy is still a kid. Is it so selfish to want to protect her until she’s an adult? Surely there will still be men for her to be with once she’s well and grown, once she’s able to make that decision, and not just be used and abused by the countless perverts who just want to slake their twisted desires, under the guise of protecting the future of Humanity.

Brad did a lot wrong. He killed, tortured, and destroyed, all for a girl who wasn’t even really his, who he was far too cruel to. But for all he did wrong, can you blame him? What else could he have done? Is it really right to just offer up an 8 year old to be raped and impregnated by the horny masses? Is that a decision anyone could make? Especially someone with a past lik Brad?

I believe what makes OMORI even more special for so many people, including me, is how it’s portrayal of these issues is so universal. I myself don’t really suffer from ptsd, or feel anywhere near the level of guilt Sunny and Basil are going through, however I strongly empathized with their struggle. I am not gonna pretend that I was ever diagnosed with depression, perhaps I should seek help, but I could see myself in the game, my own struggle against depressive thoughts, anxiety and self destruction.

By the end of the game I felt as if the game was digging just as deep into me as how much I was entranced by it. Omori’s dialogue during the final battle hitting especially hard as these thoughts were close to my own.

Celeste is by far one of the best games I’ve ever played and the one experience that will stay with me till the very end.

I love Celeste and what it is trying to make. The portrayal of mental illness as something to accept instead of ‘overcome’ or plain out ‘ignore’ (cuz boy, is that effective!) is so rare. That feeling of being trapped inside your own mind is something I can definitely relate to, and accepting it for what it is and learning to live with it instead of in spite of it works so much better than to simply ‘get over it’. It’s comforting to see that represented in media too.

I really like that you found this message in the game. Mental illness is not something you “get over” or “work through”. It is quite literally something we live with. You cannot just change who someone is and what they have experienced to that point. You cant. So all the people who dont understand, who have never had anxiety, who had pleasant experiences in their life, arent mentally trained to understand the thoughts and issues someone with any mental disorder like this.

It takes understanding. It takes compassion and trust. War cannot be won by hostility and violence, only by understanding and compassion. If you have a friend who struggles with mental illness, treat them with compassion and try to understand. And more importantly, if you yourself have these demons inside you, understand that they are not parasites to which you must eradicate, but rather, they are your essence in turmoil with your will which is too scared to show them the love in which they desperately seek. Never stop loving everything you are and do because when you embrace the pieces that make up you, you can climb any mountain you so desire.

Celeste is exactly what it feels like with my depression and anxiety. The game did such a great job explaining both, and more. I also loved the graphics and music! The game itself was amazing.

What’s great about the soundtrack especially in Celeste when it comes to representing Madeline’s struggles both physical and mental is not just how good it is and how much it gives the player a sense of the moment and drawing them in to feel much of the same emotions. Its also that the composer herself struggles with anxiety and other mental health issues like depression and she composed the soundtrack to reflect her own state of being as well. So we as the player are not just experiencing Madeline’s battle, but Lena Raine’s as well.

After watching Madeline try to work through her depression, when I beat this game I felt that I could combat my depression as well. It’s amazing that a game like this manages to do that.

I love this game. The only thing that really frustrated me was while playing it on switch sometimes she would dash in the wrong direction because I wasn’t pointing the analog stick exactly correct, and as you know, if you make one small mistake in this game usually you die. But overall the rest of the gameplay was fun and the story absolutely incredible.

Honestly one of the greatest games i’ve ever played. not only was it fun and challenging, but the storyline was super engaging, not to mention the genius that was the soundtrack.

I really like how they handle mental illness. I’ve never had panic attacks, but I did try to fight myself, well it was more like two parts of myself fighting each other, with me caught in the middle. But yeah, every time the light filled me with hope, the dark would soon throw me right back into despair, and then I’d soon be filled with hope again. It was a constant back and forth war that no side could win, and I appeared to have no control over, it sucked. Fortunately, the light and dark in me have ended their war and do appear to be working together, or at least came to a compromise

I can’t speak for everyone, but this game really felt like it understood what anxiety is like to deal with. Really touched me personally.

I really wish overcoming something like depression was as achievable as it is in this game…! Often there’s no one telling you can do it, nor there’s an assist mode…! And sometimes, even after trying and trying… you ultimately fail. I am thankful to this game though because it does get a positive message about it. With everything combined, the whole experience was positive, very much so.

I remember being legitimately angry as I played through the ending of Lisa. I had grown to despise Brad over the course of the story because he embodied not only the same abusive behavior his father was guilty of but the selfish parent attitude of “I will let the world burn to save my child”. I hated him but at the same time I still couldn’t see him as evil. He did what he thought was right and ultimately accepts that he was in fact a failure. I ended up finishing the game three times to see all three endings which is a testament to how powerful the writing is in that game. It changed the way I viewed what makes a character compelling.

I felt genuinely so bad for Brad, even loved him in a bitter sweet way. I didn’t feel irritated by him but disappointed when he failed yet acknowledged how hard he tried to redeem himself, with genuine loving intentions for his daughter… But I also kind of understood his motives and feelings… It was so powerful!

The most compelling about Brad is that his flaws are understandable due to his experience in life. And it’s ironic how in the end he basically another side of coin of the man he hates.

Brad always remind me of my dad, I mean… in a exagerated way of course. My dad grew up without a father, an abussive mother and a scummy brother. He’s always very emotional, very passionate and he had told me that he would kill if anything happens to us, that’s something that never felt “good” hearing… sometimes he can get carried away with his guts to the point that he would be somewhat scary. When my sister left the house he changed, he missed her during the first months and during that time his relationship with his mother became sickening to the point that sometimes me and my mother wanted to run away because of his rampages, until that point he always swallowed his hate and everything blew up all at once.

He’s better now, he’s a nice guy, he’s not abussive nor violent, just very passionated and as time passes on I realise more and more how similar we are, he’s just… louder.

i actually almost cried during the panic attack scene with theo, ive never seen so accurate a portrayal of mental illness and how it sneaks up on you where nobody else can see it. its a painful scene to watch, even moreso to live it, and i think its beautiful how they captured so much emotion into one scene so accurately.

I want to play these game.

Spot on. I love these games’ message, and this is a great analysis.

I related really deeply to Celeste specifically because of how honestly this abstraction/representation of living with anxiety and depression is done. I went in expecting to have fun with a hard platformer with the same kind of polish super meat boy had. I got both that and a game I’ll never forget.

Feel that Celeste is a great example of what one may go through in personal shadow working also.

This game teaches something very important, which my therapist also taught me: how to LISTEN to my depression. Instead of fighting it, I try to understand what it’s telling me. Maybe my panic attack means that I’m overworking myself and I need to ask my colleagues for help. Maybe me slipping back into depression means I’ve been neglecting myself and my social relationships. Viewing depression as a protection mechanism (which it is) and acting on it has helped me more than trying to banish it ever could.

This article is what I will share with my mother to show that video games can be meaningful!

I love how people made a game that has fantasy elements in it, but is also so hecking deep and relatable to some.

Man, indie games have made MASSIVE strides to better represent mental illness recently, and that makes me really happy to see.

The scene in Lisa: the joyful where she fights her image of Brad and her way of accepting him as her dad made me ugly cry. The music that plays in that fight still makes me feel like shit when I hear it.

LISA is phenomenal, I feel like it should be bigger than it is right now

Brad is literally the embodiment of “the road to hell is paved by good intentions”

I was a bit lost after playing Omori. I’m currently in therapy for C-PTSD, and finishing Omori a few days before my next session was disorienting and scary. Reaccessing the feelings that game provoked, was simultaneously horrifying and hopeful.

As someone who loves to interpret story and meaning from gameplay and design, there’s something Omori does that I find both genius and heartbreaking, and it’s the RPG combat. For as dark and as harrowing as the game gets, no one ever really asked for this game to be “fun”, but it is; the combat is actually extremely intuitive, as well as satisfyingly deep. Once you start piecing together synergies and combos with all your party members, you feel yourself grasping mastery over the game’s systems. At the same time, the game’s boss fights really push you to the limits of your ability, giving you both the thrill and catharsis of overcoming difficult challenges. But there’s an invisible cruelty to it all. This feeling of power and control that you have only exists in Headspace, where your friends love you unconditionally, where you can manipulate the feelings of everyone around you, where you go on adventures and defeat dangerous adversaries; none of it is real, but it’s also the most fun part of the game. Omori wants you to stay in Headspace, to play with ‘perfect’ but hollow imitations of your friends, and to give you control and power. The game even provides a harsh contrast when you get into fights in the real world; you don’t have powers, you can’t manipulate emotions, there are no skill synergies or combo attacks. Fights in the real world are clumsy and awkward (as it would be between a bunch of kids fighting in the park), and end either just by outlasting the other kid, or as a matter of some unglamorous, realistic circumstance (Knifing Aubrey, the pepper spray, etc.)

It’s in this way that Omori “weaponizes” the sensation of fun, and part of experiencing this game also means realizing how fleeting and ultimately meaningless all that fun RPG gameplay is. In headspace, you and your friends are an unstoppable force. You have “power”, but only in a domain where everything is designed to lose to you; you have “control”, but you’re ultimately still trapped; you defeat hard bosses, but nothing in the game is harder than having the courage to face the truth. Eventually, you figure out that if you truly want to get anywhere, it starts by putting down your toys.

Lisa: The Painful is highly recommended because Brad is the best fucking character in a game i ever met, he is so damn good of a character, we ALL know Brad is not a genuine bad person, in my eyes, Brad did the only right thing he could do throught out this game, he tried he REALLY tried and cared, the world was a lost cause and so was Brad but Buddy wans’t and HE cared about that, the world around her did not, i cannot get myself to hate him, and if you think about it, Buddy only got the freedom she so desired because of Brad’s acts at the end of the game, but oh god a single comment like this cannot even scracth the surface of what a pack of a character Brad Armstrong is.

I also think it’s really interesting to think why we have this rise in mental-health-related media in gaming. There have been patterns around it in indie horror and text adventures since the early 2000s. I suppose to some extent it could be the player base is growing up with the medium.

I feel as though the idea that mental health topics are overused in games has more to do with which games get popular than which games are actually being made. Even if the overwhelming majority of indie computer games don’t depict mental illness–or don’t depict it in a realistic and respectful way–if the ones that do get more attention and accolades, then this is going to create the illusion that there are a lot more games dealing with mental health problems than there actually are. Moreover, since in my experience a lot of people who play computer games regularly, particularly if they’re my age or younger, have mental health problems of one kind or another, in a way it makes sense that they would gravitate toward the games that seem to describe their specific troubles.

While I understand your point, I’m not sure if the ones about mental illness do receive more accolades and attention than other topics. The most popular games of the last year or so that I’ve seen the most focus on haven’t really been about mental illness at all.

That, however, is very much my personal experience and opinion.

I guess there are a number of people who think that dealing with emotional or personal matters like mental illness, death, or loneliness is “cheating” in a way. That seems like such a counter-productive mindset. There are definitely poorly made games that deal with such topics, but you can still tell if the game is poorly made. I haven’t played any of the games in this article, but I’ve heard good things about them. If you’re enjoying playing the game, isn’t that the point?

Thank you for this article, I really enjoyed reading it.

Another powerful example of representation of severe mental illness in a video game is Hellblade Senua’s Sacrifice. The game is about the main character living out a psychotic episode and her life’s struggle to cope with her illness. It was honestly an experience that I felt could only be done through the medium of a video game, like for example you hear voices throughout the game in surrounding audio, showing the player what it’s like to experience that level of psychosis.

It hit home for me, how people with severe mental illness suffer. My dad went through periods of time when he was completely debilitated by psychosis, sometimes for years. Hellblade helped me have a little window into what that was like for him.

I think the message of Celeste is that the ‘dark side’ isn’t really a negative think, that she isn’t really the villain, that the real conflict in the game is just to accept every side of you. That no emotions are negative, all emotions are neutral, it’s just how we live with those emotions. And that thought can also be reflected upon mental illness in all forms.

Would you consider that Madeline in Celeste has a form of schizophrenia? I have been doing a small research project for school and looked into the topic of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is considered a chronic brain disorder by many researchers (unsure if it is synonymous with mental illness). To be diagnose with schizophrenia, one must portray 2 or more symptoms (and does not need to contain hallucinations).

Though one has to know that depression can have similar symptoms to schizophrenia.

Personally, I wouldn’t say she has schizophrenia. While obviously you can definitely take that as your interpretation, I think that in the story of the game, Badeline is not a normal hallucination, but a magical one. Madeline says that she has depression in the game itself, and while misdiagnosis (or multiple issues at once) can occur, I’d never considered that she could have anything other than depression.

I think that could be an interesting topic, though. Schizophrenia is a mental illness rarely portrayed in media, and portrayed sympathetically even more rarely.

God omori literally saved my life, when i was so depressed to the point eating or even being awake was exhausting playing omori gave me life… the game made me wanna talk, laugh and enjoy life again. omori will forever be my FAVORITE game and the BEST christmas present ever :]

Fun fact!! The word “omori” (while most likely meant to be a shortened version of hikikomori) In Romanian translates to the ‘you’ form of “to kill,” so basically the game is calling you a murderer from the start

As someone diagnosed with depression and anxiety, and that has also been through a lot of trauma, Omori destroyed me. During the ending it felt like my entire world was caving in, as if i was feeling all of the exact emotions sunny was. I remember just sitting there afterwards thinking, “Holy shit. I could never forgive myself.” It’s so scary knowing that if I was ever in the same situation sunny was in, I would see no other option then ending it all. I could never live with the fact that I killed another person. Just like in the game, my mind would be at war with each other.

I agree that it’s not an over-explored topic, but I also think that it’s actually on the rise. And my only concern arises when mental illness is used in a way that downplays the actual hardships, such as in constant satire throughout a work.

Celeste is a great game! I think that as the topic of mental health is discussed more and more openly in culture/society, there will be more art (games, films, and television shows) related to the topic as well.

Wonderful post

Actually didn’t really realize how much of a trope this was until reading your article. As an avid gamer, this kind of intrigues me. I feel like after the huge success of Doki Doki Literature Club, other indie game companies saw an opportunity. A market was created. I’m sure some game devs are truly passionate about bringing awareness to mental health issues in an accessible way for mass audiences, but I think some game devs saw this opportunistically. I only really recognize Fran Bow out of all the games listed because of YouTuber Markiplier’s playthrough of it and his positive reception of it. I think it’s a cool concept if done correctly, and I think the bandwagon is what is making this corner of gaming / storytelling feel oversaturated. I’m all about a good story when it comes to games (a writer turned gamer appreciating the story? imagine) so as long as it’s done right I’m okay with different takes coming into the community in the form of different games. Mental health is a topic that needs to become normalized after all.

Great article, I hadn’t really noticed the sheer quantity of indie games that were mental illness focused but this was quite illuminating.

Great Explained the topic.

A great analysis!! I had a great time playing OMORI and Lisa and really enjoyed this breakdown and highlighting of their differences.

Very interesting piece and interesting to see some related research. Psychology research talks about mood-congruent processing which may suggest that depressed persons or persons trying to help depressed persons may be more tuned in to playing such games. There is a clear risk when suicide is an option, or the only end. Depression, being strongly perceptual and interpretive, surely means that changing thinking is one important mechanism of change. There is mountains of Cognitive Behavior Therapy research. A game that can allow for different pathways – specifically arriving at a balanced thought, activating movement and positive encounters and experiences, repeated exposures to fear and anxiety about potential problems – can support an mHealth approach that can be tested for its impact on depression scores. I wonder how many psychotherapists play such games?

I feel that mental health is not talked enough about, and having these kind of games help spread the message that it is okay to seek help, you’re not broken. Games are a great way to spread awareness.

I like the idea of difficulty of the game contributes to its overall impact of its theme to the player. On the one hand, making a game about overcoming hardship difficult to play is thematically appropriate, but alienates players of lesser skill. To offset this, the game comes with accessibility options to lower the difficulty, but it can’t be denied that this won’t work for all players. This stylistic choice, however, is what makes the game so enticing and satisfying to play, and by extension so meaningful to so many players. Balancing accessibility, difficulty and the game’s message and core principles is something that I hadn’t taken too much into consideration until now.

There isn’t a thing as too much mental wellness awareness but when it starts to glorify mental health struggles, people start to idealize and sometimes even romanticize some dark parts of mental health struggles.

yume nikki is the game you mentioned that i am the most familiar with, and it does do a fantastic job with the drastic contrast between “the real world” (dull color pallet, ost limited to silence or the ominous humming on the balcony, restrictive in that there is nothing to do and nowhere to really go except, well, bed) and “the dream world” (wild, unnerving, a lot of sudden shifts in music from entrance to entrance, almost too many possibilities and therefore overwhelming). madotsuki’s unhappy, anxious emotional state is present in both. really good game in spite of its downer ending.

Great article! I agree – with the vast amounts we know and don’t know about mental illness, exploring them in fiction is always interesting.

I’m glad someone has disproved these claims, which do feel a bit ridiculous when you look at published games as a whole industry. I would’ve loved to see a bit more exploration about /why/ people feel this way despite these claims not being back by statistics, but maybe that’s for a different article! Great read nonetheless.

“The best thing is to know that every effort you made will pay off.”

I love this paragraph:

Celeste is about Madeline’s struggles, both to climb the mountain and to deal with her mental health. By making the game a struggle to play, the player empathizes with her difficulties, and shares in both her failures and her successes. Having the game be so difficult means that the final triumph of reaching the mountain’s summit feels amazing, both on a story level (watching Madeline reconcile with Badeline and overcome her issues), and on a gameplay level (having all your platforming skills acknowledged and rewarded).