The Enduring Importance of Mother-Daughter Literature

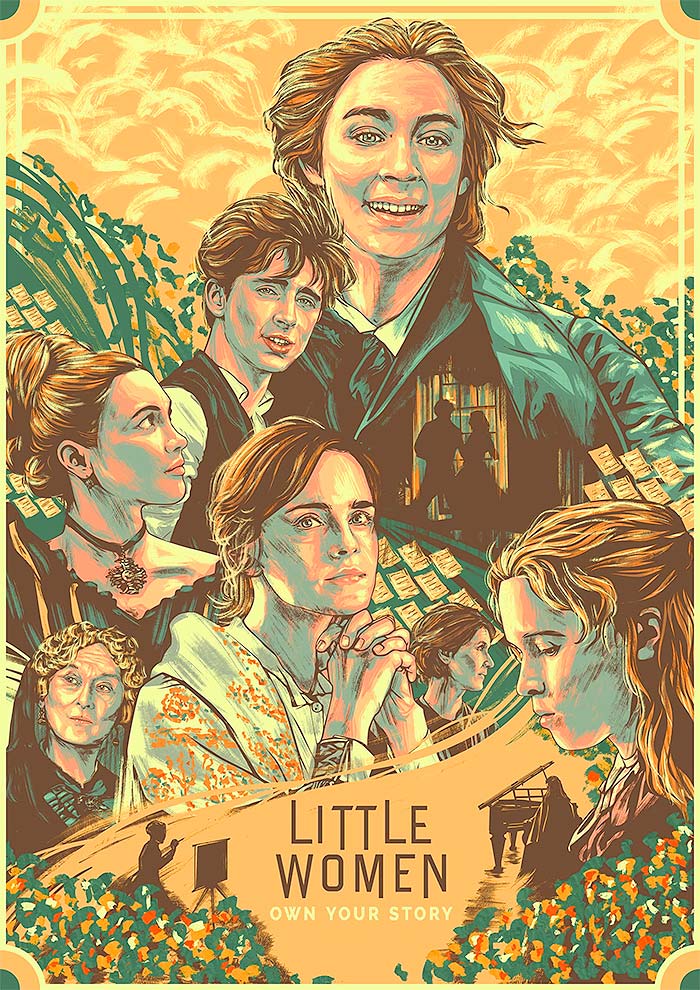

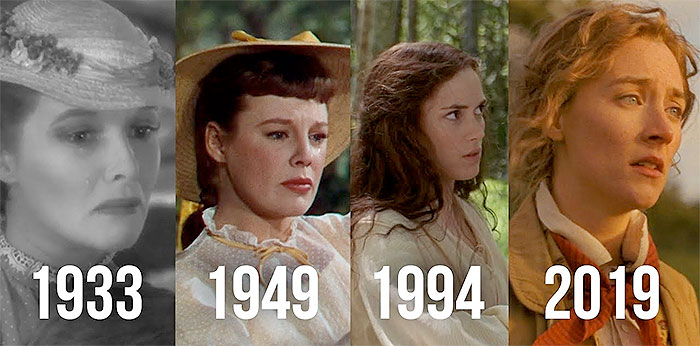

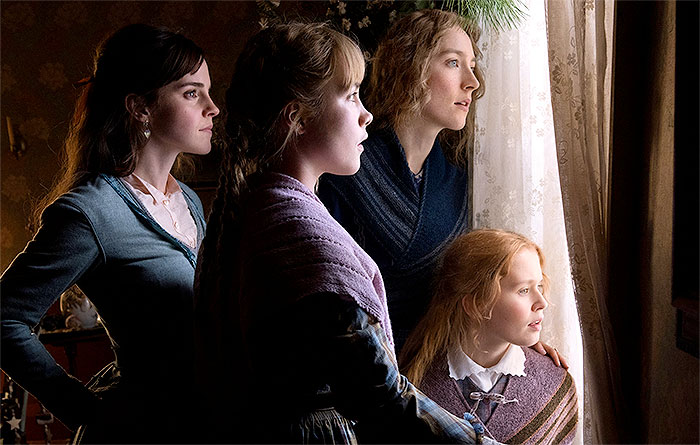

In December 2019, the film industry graced us with yet another adaptation of Little Women. Starring Emma Watson as Meg and Saorise Ronan as Jo, the latest adaptation came mere months after a modernized version of the same story, wherein Jo attends university, Meg experiments with being a party girl, and Beth dies of cancer, among other changes. While plenty of viewers and reviewers loved the December 2019 adaptation, just as many others had a burning question: why so many adaptations of Little Women? American readers and film-goers know the story. Did we need to see and hear and experience it again?

The answer is “yes,” but that “yes” doesn’t apply only to Little Women. Louisa May Alcott’s story endures because of Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy, yes. It endures because it was and is a feminist text. Yet the most compelling reason it, and other stories like it, endure and demand attention is because Little Women is a mother-daughter story. Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy can’t become who they do without Marmee. Similarly, Marmee becomes a fully realized women not because she is a mother, but because she mothers four daughters into womanhood, into “their own.” This construct has touched and continues to touch mothers and daughters across the centuries.

With all the attention Little Women receives, it certainly warrants discussion, especially as a mother-daughter story. But Little Women doesn’t stand alone. This novel is the forerunner for countless other mother-daughter stories, all of which are vital to an understanding of mother-daughter literature, feminist literature, and literature as a whole. Mother-daughter stories have evolved. They now feature diverse cultures, relationships, and expectations. Today’s mother-daughter stories feature different configurations, too. Some have one mother with several daughters, some feature multiple sets of one mother and one daughter, and others have different setups. No matter what they look like though, mother-daughter stories endure. Each mother-daughter story has something particular to teach readers and viewers about relationships and life.

For the purpose of our discussion, the simplest definition of “mother-daughter story” is a book that features mothers and daughters as main characters. However, we will probe a bit deeper. A true mother-daughter story will feature mothers and daughters, or women serving as mother or daughter figures, as main characters. These characters will be three-dimensional, defined by traits, actions, and reactions that don’t relate directly to their biological titles. The mother-daughter relationship need not drive the plot, but the story must allow both mothers and daughters to grow, learn, and become more complete people through the relationship.

Little Women

First published in 1868, Little Women is perhaps the oldest and best known mother-daughter story. It’s based heavily on Louisa May Alcott’s life growing up with three sisters (Anna, Lizzie, and May). Alcott’s father, a Transcendentalist philosopher and preacher, was often occupied with work and new ideas, such as a utopian farm called Fruitlands. Thus, Louisa’s mother Abby May “Abba” Alcott was her most present parent. As in Little Women, the Alcott girls called their mother Marmee. Louisa May Alcott was what is sometimes called an “author avatar” for Jo, meaning she and Jo are similar enough that the reader would easily recognize one as a mirror of the other. Louisa’s sisters could be considered “avatars” for Meg, Beth, and Amy. These and other similarities gave Louisa May Alcott a strong foundation for an autobiographical work, with the mother-daughter underpinnings we know and love today.

In Little Women, readers see an arguably idealized version of mother-daughter relationships. When the novel opens, Meg and Jo are already in their late teens and working outside the home, but all four girls continue living with Marmee. This is partially due to the expectations of women in the time period; the novel is set during and after the Civil War, a time where young women often did not leave home until marriage and were not given many options in regard to university or working outside the home. However, readers can quickly discern the March girls might choose to stay with Marmee even if they had other options. They are eager to help her traverse life as a single woman and parent while Father is away serving the Union troops as a chaplain. They put her needs far above theirs many times, starting from chapter one. When wealthy Aunt March gives each girl a dollar to spend on Christmas presents they wouldn’t have otherwise, the daughters eventually decide to exchange their “fun” gifts for things Marmee needs or wants. The daughters lavish Marmee with verbal and physical affection every chance they get, and show varying degrees of dependence on her as a mother. Meg and Jo still seek her out for advice or solace; Amy clings to Marmee as a youngest child naturally would. As for Beth, when she falls ill with scarlet fever, it is Marmee’s healing touch that brings her back to health. “Beth needs Marmee, she depends on her,” Jo points out in the 1994 adaptation when she and Meg debate whether to send for Marmee, which would require her to leave wounded Father alone in an army hospital.

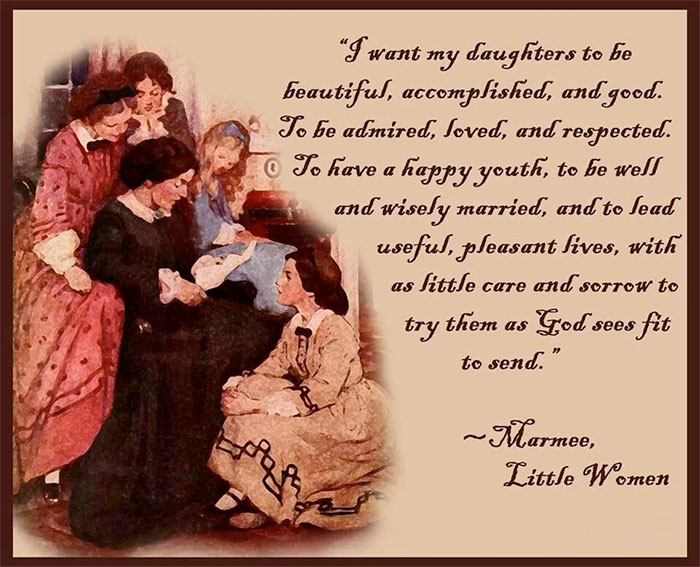

In return, Marmee is an ideal mother for her “little women.” The three most recent film adaptations in particular show she is a woman ahead of her time in her philosophies on child-rearing and the role of women in the world. Understand that “forward-thinking” doesn’t mean “twenty-first century thinking,” though. Marmee is not a modern feminist in an 1860s body. She still expects obedience even from young adult daughters, and still holds up marriage as a good option for women who aren’t independently wealthy, perhaps the best option. The difference between Marmee March and other women of her era, either fictional or not, is in how she expresses her opinions and goes about ensuring her daughters’ future.

Many of Marmee’s “non-traditional” leanings come through best in small moments during the novel or various films. The 1994 adaptation, for instance, saw Susan Sarandon waxing eloquent about girls being “no different than boys in their need for exertion,” blaming “feminine weakness” on “[confinement] to the house…and restrictive corsets”–to a male, university-educated teacher, no less. The 2019 adaptation shows Marmee (Laura Dern) as an avid supporter of her daughters’ “theatricals” (most adaptations don’t have her at home while the girls perform Jo’s latest play). Even in film adaptations as old as 1949, Marmee comes across as unusually forward-thinking. In the 1949 version, Marmee, played by Mary Astor, discourages her daughters from marriage, particularly marriage to rich men, if it would make them unhappy and shrewish. “I’d like to see you marry rich men if you love them,” she says. “But I’d rather see you…[as] respectable old maids than queens on thrones without peace or self-respect.” For the Civil War, or even 1949, such views would’ve been downright radical. Yet they serve Meg, Jo, Amy and even Beth well, giving them senses of self and security that most women, real or fictional, struggle to find and keep hold of no matter their eras. Perhaps Marmee, then, is one reason why Little Women has received so many adaptations on film, on stage, or in miniseries–because every “little woman” needs a mother figure who will teach her how to navigate her era with grace, but without objectifying herself.

With all this said, new readers could easily assume Marmee and the March girls are perfect angels. In truth, it is when either party shows flaws that their relationship becomes more idealized and worthy of envy if not emulation. For instance, Marmee admits in the novel and some adaptations that she still struggles with a temper and urge to lash out. At times, she doesn’t quite succeed in resisting said urge. When Amy comes home from school with an injured hand and reports her teacher hit her, Marmee is incensed, as she should be (although again, maybe anachronistically–corporal punishment in school was totally acceptable at the time). However, Amy blunders when she laments losing the limes that got her struck in the first place. “I’m not sorry you lost them,” Marmee snaps in the versions where we see her reaction. She goes on to call limes “frivolous” and accuse Amy of acting shallow and spoiled.

Is she right? Yes, absolutely–but did Amy need to hear it that way, in that moment? Arguably, no. Marmee may have done better to comfort Amy then, and talk over the ramifications of the incident later, when hand and heart had a good chance to heal. This said, Marmee’s reaction shows she is human. Amy’s later character development into a more level-headed woman suggests she worked on “fashioning [her] character” after that difficult lesson. She remains spoiled; a lot of readers get angry with her for “stealing” everything Jo wanted, like the trip to Europe and arguably Laurie. But Marmee’s love, “tough” though it was at times, has shaped Amy into a charming, beautiful, exuberant woman who expects the best, no longer from material goods but from the people around her. Echoing Marmee and Father’s Transcendentalist philosophy, and the similar philosophy of the Alcotts themselves, Amy “transcends” her baser nature somewhat. As she grows, her good choices become less about being an obedient youngest child, or an ideal child of her time period, and more about becoming a young woman who puts others first in the name of self-improvement.

Amy’s change for the better is especially clear when she confronts Laurie in Europe. “I liked you better when you were blunt and natural,” she says in the 1994 film. “You laze about spending your family’s money and courting women…I despise you,” she adds. When Laurie tries to tell Amy she could make him better, and that her family has always been a steadying influence in his life, she calls him on it. “I do not wish to be loved for my family,” she says, hearkening back to Marmee’s insistence that her “little women” will be loved for nothing less than who they are. Furthermore, those people will be the best versions of themselves.

Marmee’s wisdom comes to the forefront in interactions with Jo, too. As noted, Jo might be the March girl who is most like her mother, if not the one closest to her. Once again, it is during less-than-perfect situations that the mother-daughter relationship shines. Throughout Little Women, independent Jo is the daughter who pushes away from Marmee the most, losing herself in fictional worlds or going outside the home to find provision for her family while the other three don’t stray too far from the hearth. But when Jo refuses Laurie’s proposal and finds out Amy has won Aunt March over, thus earning a trip to Europe, Jo is devastated. It’s Marmee she turns to. “I’m ugly and awkward and I always say the wrong things…I’m…fitful and I can’t stand being here!” she exclaims. Her hair flies in all directions along with her emotions, and Marmee is the calming bulwark in the storm. “My Jo, you have such extraordinary gifts. How can you expect to lead an ordinary life?” Marmee asks. She encourages Jo to go to New York, a real test of whether Marmee can put her money where her mouth is when it comes to parenting. Remember, in the late 1860s, women did not usually travel out of state to pursue careers, particularly male-dominated fine arts careers. Furthermore, Jo remains an inexperienced writer and woman at this point. She has sold a few stories to magazines, but has never faced a serious editor or publisher. Her stories are extremely genre-specific and to the trained editor’s eye, melodramatic and lurid, something she’s never heard before. Jo has also never lived away from home, and because she eschews parties, balls, and the like, doesn’t have a social circle.

In other words, any other mother in Marmee’s shoes, whether she lived in 1868 or 2020, might not send Jo to the state capital, let alone New York, while both mother and daughter’s emotions were fragile. Is Marmee giving Jo too much latitude? Is this another example of arguably misplaced “tough love,” like with Amy and the limes? Careful analysis indicates “no” to both. Marmee’s decision to let Jo go, to let her “try her wings,” comes from the heart of the best kind of mom a child in any century could have. Marmee is a mom who knows her kids inside out. She knows how to nurture their strengths and carefully navigate their weaknesses. Thus, she knows telling Jo to stay in Concord, calm down, and wait for life to come to her would backfire. Instead, Marmee does her due diligence, setting Jo up with a job and a place to stay, but then lets her figure out the rest. The result, as we know, is an unexpected but satisfying ending for Jo. One could argue that Jo, like Amy, comes to her “happy ending” because she learned, in some measure, to “transcend” her faults and accept the situation life steered her toward. Is it the ideal for a woman of her time? No. Is it the one every reader wants? No; modern readers still argue that Jo should’ve accepted Laurie. If we could ask Jo or Marmee though, they would probably say they did well as a mother-daughter team on that one.

Mother-daughter relationships are all well and good when your youngest child needs you, of course. They can lead to fantastic character growth when your daughter shares your personality. But what happens when daughters reach life stages that seem beyond the reach of that relationship? For Marmee, that question comes with two identities attached. What about Meg and Beth?

As Little Women opens, Meg is already fairly secure in her identity and has embraced the expectations of an 1860s woman. One of the only private moments we see between Meg and Marmee in the novel or films occurs when Meg yields to temptation at a friend’s debutante ball. She drinks champagne despite her “temperance” upbringing, flirts with strange men, and wears a revealing-for-the-era dress. Meg comes to regret her behavior, but tells Marmee she couldn’t help but enjoy the attention her worldly actions garnered. Marmee empathizes, and Meg ostensibly learns to be herself, never to encounter her insecurities again. Yet they continue popping up during the novel, even after Meg’s seemingly perfect marriage to John Brooke. The 2019 adaptation is the first one to acknowledge this, giving us a scene between Meg and Marmee (Emma Watson and Laura Dern) after the former buys an expensive dress without John’s knowledge. With two small children at home and John the sole breadwinner, money is tight, and Meg’s splurging makes John think he will never be good enough for her because he can’t afford to buy her luxurious items. Meg opens up to Marmee about her desires and her foolishness, asking how to mend fences. Again, Marmee mixes hard-hitting advice with empathy. She, too, has been a young wife who had to learn to balance her family’s needs with her own. She, like Meg, remembers days of prosperity and still longs for them. Perhaps most importantly though, hearing Meg lament her choices makes Marmee realize some foibles never go away no matter how old we are. The dress scene is a major bonding moment for her and Meg, serving to strengthen the mother-daughter relationship, Meg’s marriage, and the relationships Meg will eventually build with her kids.

What if, despite all your efforts and despite your almost perfect mother-daughter bond, you lose a child? Marmee faces this question, as does third daughter Beth, in Little Women‘s second half. Beth is the homebody March daughter, with shyness so intense that today, we’d call it disabling social anxiety. Also, Beth is emotionally and physically fragile, with her major story arc centering on illness and recovery. Amy is the youngest, but Beth is the one Marmee actively nurtures the most, worrying over her, calling her “Cricket” (as in, cricket on the hearth), and not insisting she face her fears. Readers don’t know why Marmee would not push Beth when she pushed the others, but maybe it was because Beth was the quintessential good girl. Beth asks for next to nothing, puts others above herself almost to the point of martyrdom, and has an almost superhuman ability to extend grace and mercy. Why would a mother push a daughter to be perfect when by all appearances, the daughter already is?

Of course, there is another theory behind Marmee and Beth’s relationship. This writer wonders if somehow, Marmee and Beth both knew the latter would not live long. The 1949 and 2019 films give credence to this theory. In the 1949 film, where Beth is portrayed as the youngest sister, she tells Jo, “It seems I was never intended to live very long.” The 2019 film shows Marmee warning Jo that Beth’s death is imminent, and speculating on life’s general meaning. The 2019 scene shows how Marmee’s idyllic relationship has spread to all four daughters. That is, Beth was the daughter to whom Marmee was physically closest. They likely had plenty of time to talk, learning from and about each other, and about more philosophical topics. Thus, one would expect Beth’s passing to shatter Marmee to the point of no return. But while Marmee grieves bitterly, she is able to let Beth go. In the novel and the films that show Beth’s passing (the 1949 film does not), there is a sense that Marmee has reached the pinnacle of motherhood for at least one child. She has successfully raised someone perfect–perhaps too perfect–and now the test of motherhood lies in giving her up. The fact that Marmee can do this with grace, while symbolically releasing her other three girls at the same time, underscores how successful their relationships have always been.

The Joy Luck Club

In some ways, Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club couldn’t be more different from Little Women if it tried. First published in 1989, The Joy Luck Club arrived over a century after Alcott’s masterpiece. While Joy Luck has achieved great critical acclaim, it is a much “younger” book with an overall smaller audience. The story focuses not on one mother and four daughters, but four mother-daughter sets, doubling the cast size and demanding a different form of storytelling. The protagonists are Chinese-American, not white, and while the mothers’ stories take place in a different era and country, the daughters are modern (for the time) American women. However, The Joy Luck Club is a compelling mother-daughter story, or set of stories. It contains almost none of Little Women’s idyllic tone, but comforts and encourages in its own way. In fact, if Marmee and the March daughters could have read Joy Luck, they might well have seen themselves in, and applauded, the characters.

The Joy Luck Club doesn’t begin until one mother, Suyuan Woo, has already died, and her daughter June is asked to replace her at the mahjongg table with her aunties. Aunties Lindo, An-Mei, and Ying-ying had known Suyuan for years. They were all best friends, attending the same church and carrying on the tradition of the Joy Luck Club from their days in China. As June tells us, “They played [mahjongg] and laughed, lost and won, and told the best stories.” In World War II China, in fact, the hope of being lucky at mahjongg was the women’s only joy. The aunties hope to share this, and memories of Suyuan, with June, and are appalled when June admits she feels like she didn’t know much about her mother. “How can a daughter not know her own mother?” Auntie Lindo demands in the film version (1993).

It might seem paradoxical, but for the Joy Luck Club ladies, it’s true. The four mothers and daughters don’t know each other like they think they do. In many ways, they never have. Their relationships are not nearly as tight-knit and loving as Marmee’s relationship with Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy. Yet this doesn’t mean the relationships are hopeless, or that they are not valuable. For the rest of her novel, Amy Tan uses vignettes from each woman to show various nuances in more complex, realistic, and “modern” mother-daughter interactions. The vignettes move out from the central incident of Suyuan’s death and June’s initiation into mahjongg like spokes from a wheel or petals from a flower, until they form a perhaps imperfect but complete picture.

One of the key differences between the interactions of Marmee and her daughters vs. the Joy Luck mothers and daughters is, at least two mothers are noticeably stricter than Marmee. Marmee combined her strictness with direct life lessons, such as with Amy and the limes, or a chapter in the novel wherein she let the daughters take an entire week off work and chores with no consequences–that the girls could immediately see. With the Joy Luck mothers, life lessons are not always apparent, and strictness comes off as harsh. In one flashback, June relates how she protested playing the piano after messing up royally at a recital. Suyuan won’t have it, and insists only obedient daughters will live in her home. She doesn’t abuse June in any way, but Western readers might wonder why a mom would supposedly make such a huge deal about piano playing. Why could she not be more empathetic? The same questions arise when Waverly’s mother Lindo berates her after she quits chess–because Lindo had continually embarrassed Waverly about her chess talent, and taken credit for her wins. “It is not so easy, one day quit, next day play,” Lindo says. She’s proven right, as Waverly loses her next match and presumably others. But again, her methodology leaves something to be desired in the eyes of most Westerners.

It would be easy to say the difference between Marmee, Lindo, and Suyuan exists because the latter two are “tiger mothers.” Even some Asian authors, such as Amy Chua, author of Battle of the Tiger Mother, might use this moniker. Chua and others raised in this same environment testify to “adoring” their parents. But to say Suyuan and Lindo are “tiger mothers,” and this ruined their mother-daughter relationships, would be criminally simplistic, stereotypical, and racist. The actual difference lies in where the Joy Luck mothers have come from, and how they have processed their lives’ events. As their daughters learn, their mothers’ lives have almost nothing in common with theirs; simultaneously, their lives have everything in common.

Suyuan, for instance, has every reason to privilege obedience over June’s perceived happiness. She was a first-time mother during World War II China, to twin baby girls. But unlike Marmee, who’d had years of financial hardship before wartime, the travails of World War II hit Suyuan head-on and somewhat unexpectedly. In one of her vignettes, she explains the Chinese people were often told the Japanese were not a threat, when China was actually in imminent danger. Thus, Suyuan finds herself among thousands if not millions of refugees, carrying her worldly possessions, plus two newborns. In the 1993 film, we see her forced to leave the babies at the roadside, too exhausted to carry them and screaming for help that never arrives. Readers and viewers aren’t privy to the time between that trauma and the years up to and after June’s birth. But when Suyuan insists on obedience, we hear more than a strict mother. We hear a mother who insists on perfection from the child she has so she will not lose her, too. We hear a mother trying to mold a daughter into the child she dreams of, because she only has one chance to be a good mom.

Similarly, Lindo Jong, “Auntie Lindo” to June, appears self-serving regarding daughter Waverly’s chess talent. “I tell my daughter, ‘Use your horses to run over the enemy,'” she tells a friend, implying Waverly isn’t smart enough to know how to move a knight. Waverly blows up and vows to quit chess, leading to the aforementioned breakdown in her self-esteem. Several years later, we hear her tell Lindo, “You don’t know the power you have over me. One word from you, one look, and I’m four years old again crying myself to sleep.”

Such power seems abusive, but it comes from a well-intended, if trauma-driven, place. Lindo was forced into an arranged marriage in China at age fifteen. Her husband was a prepubescent boy, and they “slept like brother and sister” for months, maybe years. Lindo was blamed when grandsons did not arrive for her cruel mother-in-law, and placed under strict isolation. Lindo’s quick thinking saved her emotional and mental, perhaps physical, health. She convinced her husband’s family an ancestor had come to her in a dream, threatening the couple with disaster and illness if she stayed in the marriage. She also claimed a pregnant servant girl was her husband’s “true spiritual wife,” according to the ancestor. As Lindo sums it up, “Huang Tai-Tai got her grandson, the servant girl got a marriage, [and] I got a rail ticket to Shanghai.” The traumatic marriage left marks on Lindo, but here, we see it made her cunning and self-reliant. She learned no one else was going to get her what she wanted, whether that was freedom, love, or a prodigy daughter who could be smarter and stronger than herself, and therefore escape life’s pain. Thus, as wrong as it might seem, she took Waverly’s credit not out of maliciousness, but out of a true belief Waverly couldn’t succeed without her.

Aunties Ying-ying and An-Mei continue this trajectory with their daughters Lena and Rose. As with Suyuan and June, Lindo and Waverly, the mothers have experienced trauma and the daughters assume said trauma does not affect their modern, American lives. Like the other daughters, Lena and Rose discover their mothers’ pasts can influence them for good, but in different ways than Lindo’s or Suyuan’s did. Rose and Lena are more introverted and demure than Waverly or June. They connect and disconnect with their mothers differently, so when their adult lives take turns for the worse, Rose and Lena learn from their mothers in different ways.

Auntie Ying-ying and Lena make this connection first, when Ying-ying visits her daughter and son-in-law shortly after the couple buys a new house. Ying-ying complains the house, one room in particular, is “crooked.” At face value, this looks like a superstitious gripe. Lena assumes Ying-ying is talking about feng shui, or fears bad spirits will enter the house. Bad spirits actually are part of what Ying-ying fears, but there’s another layer under her complaint about a crooked house. Ying-ying is more upset that Lena treats her marriage like a balance sheet. Again, there is a “face value” version of this, plus another layer. Lena and her husband Harold have agreed to share everything as equally as possible so their marriage will be fair. Exceptions exist; Lena notes Harold doesn’t pay for her tampons or feminine hygiene spray, and she lets him read magazines she subscribes to “because they’re there.” However, Lena always comes out with the worse end of an “equal” split. If she has a salad when they go out to dinner and Harold has three courses, Lena still pays exactly half the check. If the cat Harold gave her as a birthday gift contracts fleas, Lena pays the entire bill to eradicate them. Ying-ying also notes Lena will pay for things only Harold uses, such as ice cream. “Lena cannot eat ice cream,” Ying-ying protests when she finds out, adding it makes Lena sick. Ice cream seems like a small thing, but Ying-ying gets the deeper meaning; Lena’s marriage, too, is sickening her. She’s being treated as a lesser business partner, and it’s weakening her spirit.

Lena sees the truth too, but like June or Waverly before her, she can’t admit her Chinese, Eastern mother’s approach might be superior to the Western, American one. In the novel, there’s a resentful undercurrent to this. Lena has watched Ying-ying traverse clinical depression, often without much improvement. She has never seen her mother act “strong” in the way Americans think of it. So what could Ying-ying possibly say or do to cut Lena’s spirit loose, as Ying-ying herself puts it in a film monologue? Actually, Ying-ying could do a lot. Like Lena, she went through an unequal marriage, although hers was physically, emotionally, and mentally abusive. She met her husband at a young age and got swept up in his charisma before discerning his true nature. Eventually, this led to depression so intense, she drowned her baby in his bathtub. Ying-ying remarried and emigrated, and as far as readers know, never spoke of the dead baby. The subtext though, is that she lost her little son, and part of her life, because her spirit wasn’t strong enough. To protect Lena, Ying-ying doesn’t become a “tiger mother.” Instead, she becomes a tiger who “crouches in the bush, ready to leap out and cut a spirit loose.” Indeed, when she confronts Lena with the truth about her “crooked house,” Lena is able to face it. Perhaps because of her mother’s cautionary tale, perhaps because her own spirit had boiled under the surface for years, Lena leaves Harold and starts seeing herself as an “equal”–equal to other people, worthy of what she needs and wants.

Mother An-Mei and daughter Rose follow a similar trajectory, though again, with individualized differences. An-Mei, for instance, is the only Joy Luck mother we follow mostly through childhood, not adolescence or adulthood. Her vignettes are those of a girl about eight or nine, who spent her early life motherless because her grandparents disowned her mother. An-Mei carries emotional and physical scars from uncaring relatives; one vignette focuses solely on the neck scar An-Mei sustains from a spilled trivet of scalding soup. But it is not until she is reunited with her mother that An-Mei learns all she needs to know about protecting her spirit.

An-Mei’s mother takes her to live in her husband’s home, where An-Mei learns her mother is a concubine or “Fourth Wife” to Wu Tang. As Fourth Wife, An-Mei’s mother has no standing and no household rights. An-Mei, a daughter from another time, is the only thing she has that’s truly hers. Wu Tang’s favored first wife tries to turn An-Mei’s allegiance, giving her a pearl necklace and cajoling her to “call me Big Mother.” An-Mei’s mother faces the family’s wrath when she protests and denies An-Mei a relationship with First Wife and those connected to her. Still, she cannot shield An-Mei from dysfunction entirely. An-Mei is thrown out of her mother’s bed one night because Wu Tang wants sex, and readers can presume rape followed. An-Mei also has to cope when her mother commits suicide.

But unlike the daughters before and after her, An-Mei knows her mother did not die a subjugated woman. Before her death, An-Mei’s mother revealed some valuable secrets. At one point, she smashed Big Mother’s pearls, revealing they were only glass, and thus revealing An-Mei’s relatives were offering her false love and security. She also told An-Mei that she had been married before and was a First Wife. An-Mei uses this information and the experiences that came with it to honor her mother. She plays on the weaknesses of Big Mother and her allies, reminding them her mother died near Chinese New Year. Tradition says that to anger a spirit on New Year is to bring intense, long-lasting misfortune–so An-Mei’s relations are careful to treat her well. Though suicide is considered a dishonorable act, An-Mei’s mother’s final choice ensured justice for both generations.

Decades later, An-Mei has immigrated to America and had a daughter of her own, Rose. Like Lena, Rose has a demure, introverted, introspective spirit. Like Lena, Rose’s desire for peace sometimes means she doesn’t stand up for herself or do the right thing. This is particularly true in her marriage and associated relationships. When Rose first met her future mother-in-law, the woman made sugary, condescending remarks about Asians. Rose’s future husband Ted told her off for it, but then tried to smooth things over, telling Rose she never meant what she said. Rose absorbed the message, “smooth things over, keep the peace,” and that characterized her marriage for years.

Ted is never abusive toward Rose, but readers do see he makes a lot of decisions and holds a level of power over her. Rose’s entire existence revolves around making and keeping Ted happy. She’s done this so long, it becomes automatic, such that when mother An-Mei seems disturbed, Rose is perplexed. Why, she wonders, would Mom think it’s weird for her to make chocolate peanut butter pie–a dessert only Ted eats–on a regular basis? Why would Mom ask probing, personal, and offensive questions about whether Rose has ownership in the house and what she is “worth,” monetarily and otherwise, to her husband? The subtext of Rose’s introspection becomes, what has she ever been worth, and why does it matter? Should it matter if she is happy, so long as Ted is happy?

Note that An-Mei doesn’t confront Rose boldly, the way Suyuan or Lindo would confront their daughters. In the film version of Joy Luck Club, she actually has one line that could count as confrontation: “[I’m] talking about what you’re worth.” But that line sticks in Rose’s head and heart, the same way a broken strand of glass pearls and the deathbed confession of a First Wife stuck in An-Mei’s so long ago. Readers and viewers absorb the shock with Rose as she confronts what she’s always known–Ted’s been having an affair for some time. Thus, Rose is worth less, if anything, to him, as is their marriage. The film turns this into a powerful scene as Rose confronts Ted in the pouring rain on their porch. “What’s her [freaking] name?” she demands, and when he won’t tell her–won’t admit to the affair–she adds, “Get out of my house.” He does. Like An-Mei before her, Rose uses the brief information and keen insight she has to protect her spirit.

The Joy Luck mothers and daughters are in many ways miles apart from Marmee and the March sisters. Still, the mother-daughter connection remains across age, countries, cultures, and choices. As Marmee taught her daughters to function in a world readers now view as antiquated, the Joy Luck mothers combine the best and worst of Eastern and Western wisdom to forge their connections. But does mother-daughter literature need multiple daughters, multiple cultures, or even a traditional mother figure to hold up? Some more recent mother-daughter literature would say no, and it has much to teach us about how mother-daughter relationships continue evolving.

The Bean Trees

In the late 1980s, prolific author Barbara Kingsolver gave us The Bean Trees. The novel has since gone through a few reprints and is still widely read and appreciated. It’s often used in high school English curricula and considered a young adult novel, but could also be considered adult. Its “crossover” appeal gives The Bean Trees an arguably wider audience than the other two novels we’ve discussed, and its characters lend a new perspective to “traditional” mother-daughter literature.

You could call The Bean Trees a definitive example of nontraditional mother-daughter literature, and you’d find massive evidence for that, starting with its characters. Main character Marietta Greer, who rechristens herself Taylor, wants nothing less than motherhood. She’s grown up in a rural town where the majority of girls her age drop out of high school, often because they got pregnant. She also works at the local hospital and has seen the fallout of teen pregnancy and familial dysfunction up close. Her “inciting incident” occurs when she has to treat Jolene, a high school classmate with a toddler, who saw her father-in-law shoot her husband. The husband dies on a gurney, and Jolene is hysterical. We’re meant to assume she’ll be left in dire financial and personal straits. Marietta/Taylor doesn’t blame the child for this, but she’s seen stories like Jolene’s play out one time too many. They instill such fear of failure, poverty, and lost potential in her that she has to get away. She leaves her town without a destination in mind and decides to rename herself based on where her car finally breaks down. This happens to be near Taylorville, OK, where she finds an unexpected “stowaway.”

After her car breaks down, Taylor stops at a local bar hoping to grab some food and use the phone. A woman who looks Native American watches her the whole time while holding a baby. Taylor is gobsmacked when, as she’s leaving, the woman approaches her with the bundle and pleads, “Take her.” Taylor has no idea who this woman is, why she’s pushing the baby on her, or who else might be related to the infant. In the 1970s, where the book is set, Taylor doesn’t have much recourse in terms of finding a social worker or calling the police, mostly because she suspects one of two rough-looking men in the bar knows the woman and might place the baby in a bad situation. Within a few pages, readers see a desperate teen take over guardianship of an equally desperate, helpless baby, thus becoming the mother she never wanted to be.

A “classic” and idealized mother like Marmee March, or any of the “modern” yet “tigress” mothers from Joy Luck, might fear for the baby at this point. External signs indicate they’d have good reason for that fear. Taylor calls the baby Turtle, which is in no way a traditional name or arguably a decent one; it’s the kind of name bigger kids love to taunt. Taylor also begins “raising” Turtle on the road, seeking shelter first in seedy hotels and then in apparently random locations. It takes awhile for Taylor and Turtle to find stable influences and caregivers as they bounce around. They spend time in an unconventional household that embraces every stereotype of hippie culture. Turtle is often dropped off at a mall daycare center while Taylor works, even though said center is miles from her workplace and even though it is not meant as a daily care option. When Taylor and Turtle do find a place to land, it’s with Mattie, who owns Jesus is Lord Used Tires and isn’t used to having little kids around. Turtle seems to do okay physically in these environments, but it’s difficult for Taylor or anyone else to gauge how she’s doing emotionally and socially. Turtle is clingy, doesn’t babble or speak much, and doesn’t seem overly engaged with anyone at first. Strangers speculate she is autistic or, in the words of the day, “retarded,” which irks Taylor and makes her more determined to prove she and Turtle can not only survive on their own, but thrive. Yet with such a rough start, it’s unclear at first whether Kingsolver will let them.

Fortunately, Barbara Kingsolver stays true to her unconventional story, letting Taylor and Turtle thrive in unconventional ways. More than that, both the young woman and the little girl are positive influences on those around them, especially women. Turtle finds herself with more mother figures than just Taylor. Moreover, both she and Taylor find themselves learning and growing in the presence of the eclectic cast. Mattie, for instance, is a wise mentor figure, but is not shy about stepping back and telling Taylor to make her own decisions. After all, Mattie figures, if Taylor was self-determined enough to get out of her impoverished hometown and take on a baby, she’s self-determined enough to carry through on the associated responsibilities. In another instance, Taylor is shocked to learn that the elderly Edna Poppy is blind, and that her neighbor Virgie Parsons has served as Poppy’s guide for as long as Taylor has known her. This allows Taylor to rethink her first impression of people who come across as negative or rough-edged–the kind of people she has trained herself to avoid. She can’t always relate to Poppy and Virgie. Despite the generation gap though, she can appreciate their quirkiness and the ways they cope with life, such as how Poppy gravitates to red because it’s one of the few colors she can see.

Through letting seemingly random people into hers and Turtle’s lives, Taylor also learns the various nuances of being mothered. We’re meant to understand Taylor’s biological mother Alice was a good woman, but that poverty and single parenthood influenced her availability. We get the sense throughout The Bean Trees that Taylor has raised herself, which makes her cagey about accepting “mothering” from anyone, even if she accepts it for Turtle. However, in time, the women around her change this.

Along with Mattie, Lou Ann Ruiz might be the best example of this. From the outside, it appears Lou Ann should have an ideal family. She’s married to Angel Ruiz, a man she fell for “at first sight,” and is mother to Dwayne Ray, a thriving, “normal” baby born on New Year’s Day. But as Taylor soon learns, Lou Ann struggles on many fronts. She lives at a low socioeconomic level, and Angel is gone more than he is present. He lost a leg to a rodeo injury, and living with a prosthetic has made him a bitter man. Lou Ann also struggles with self-esteem, making constant negative comments about her appearance and situation. She constantly regales Taylor, Mattie, and others with horror stories she reads in the news–tragic accidents, babies choking to death, and the like. But as Taylor matures, she discovers Lou Ann has some useful humor buried under her gloomy exterior. Additionally, she and Dwayne Ray show Taylor survival is possible, even and maybe especially for people the world counts as “misfits.”

Taylor reaches the pinnacle of growth when she not only accepts her place as a thriving misfit, but step in and help others like her. Several examples exist in the novel, but the most life-changing one occurs when Taylor agrees to get involved with Estevan and Esperanza. The couple are illegal Central American immigrants living in Mattie’s building with her blessing, but without the knowledge or blessing of the larger community. When a news report exposes them, Taylor has every reason to stay out of the situation. Her custody of Turtle has been questioned by now, with a social worker planning to take the baby into foster care ASAP. She doesn’t need anymore problems, so why does she find herself volunteering to drive the couple to safety?

At first, Taylor tells herself she volunteered because Estevan and Esperanza are her friends, and because former professor Estevan has taught her a lot about the situation of Central Americans in the U.S. and his home country, Guatemala. Both these things are true. On the road though, Taylor finds herself reflecting on these lessons, especially the story of Estevan and Esperanza’s little daughter Ismene. Ismene was killed when she was about Turtle’s age, thanks to the government her parents escaped. On their journey to sanctuary, Taylor helps them pretend Turtle is Ismene in order to divert immigration agents’ suspicions. It works, and Taylor begins reflecting on the value of the mother-child relationship, traditional or not. As part of this, she gains confidence in her ability to mother Turtle, which gives her the courage to advocate for both of them with the social worker. Turtle stays in Taylor’s custody, and Taylor contacts Alice, who expresses surprise, but pride in her choices. Taylor becomes the mother she never thought she could be, largely because she involved herself with the people and situations she grew up doing everything to avoid. Taylor will never be Marmee March or any of the Joy Luck moms, nor does she have any desire to be. But she and Turtle are going to grow into the mother-daughter relationship beautifully, because they have the experiences and support systems that work for them.

In exploring these themes and making these plot choices, Barbara Kingsolver was somewhat revolutionary with her mother-daughter novel. In 1987, single parenthood was becoming more common, but was still not considered the “ideal” for kids. In fact, plenty of people decried it, frowning on or outright demonizing single moms unless they were widowed (and sometimes then as well). The idea of a teen raising her own baby would’ve been scandalous, let alone the idea of a teen raising a stranger’s baby, who also happened to be a different race and possibly disabled. But placing Taylor and Turtle in that situation forces them, and readers, to confront a universal truth about parenthood. That is, there aren’t any perfect parents. There might be an ideal in a given person’s mind, but few if any of us reach it the way we expect to. In reality, parenthood usually forces us to admit we’re unsure what we’re doing. Mothers in particular risk their bodies, and definitely their hearts and souls, to love, nurture, and raise children. The fact that they do, and can produce functioning children with or without a co-parent, is an act of ultimate commitment. It is an act of incredible selflessness, whether or not the mother considers herself “selfless” or “perfect.” Any child will carry some sense of this with them, but perhaps the daughters will grow up with a deeper sense of their mothers’ struggles, sacrifices, and triumphs. Thus, the mother-daughter cycle continues, on and on through decades, centuries, and eras.

In Praise of Mothers and Daughters

From the first publication of Little Women onward, readers have been fascinated with mother-daughter literature. Mother-daughter relationships might not be traditional in these books. In fact, most YA and adult literature of the past several decades has not featured traditional or idealized relationships. In some cases, the mothers and daughters a book centers on are not biologically related, or are not mothers or daughters to each other. However, this type of literature’s diverse characters, and the nuances of their experiences, lend much-needed relevance to mother-daughter literature. It may not be its own genre quite yet, but if the trend outlined above continues, the mother-daughter genre could become one we not only need, but relish deeply.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Little Women remains one of my favourite novels. The family dynamic is just one of the reasons why this book has stood the test of time. The Joy Luck Club sounds good, though. On my reading list!

I think you’ll enjoy it. 🙂 As for Little Women, it was a favorite of my mom’s, and then mine, so there’s a “family legacy” element there. I’ve loved it for years…although if it were up to me, of course, Beth would have lived.

I have been meaning to pick up Little Women for, probably, a year at this point. Reading for uni always prevails over my own reading for pleasure unfortunately 🙁

But I really enjoyed your analysis and feel more inclined to find a copy and get to reading!

Oh, yes, reading for uni (or college–I’m in the U.S.) will always wreck your reading plans. I used to laugh so hard at people who thought being an English major meant I had unlimited time to read whatever I wanted.

In Bean Trees, the scene in the adoption office was heartbreaking.

Amy Tan really knows how to hit you in the feels.

Yes. Yes, she does.

Some of women’s stories in TJLC bored me and a couple frustrated me with their “do as I say, not as I do” attitudes. I realize that this is a somewhat common philosophy among mothers {Err, not you, Mom}, but I couldn’t help but to yell at these women for criticizing their own daughters as they chose their own courses, when some of them did the exact same thing in China.

Agreed. I had some of the same thoughts when I first read it. I also thought most if not all of the mothers were un-supportive if not borderline abusive. But I think that’s a knee-jerk reaction from a WASP reader who didn’t grow up around any Eastern cultures at all. As I tried to express in the article, there are so many more nuances and complications to those relationships that Western readers may not “get” because we don’t share certain lived experiences.

I think the relationship between mothers and daughters is really complicated and interesting, particularly in The Joy Luck Club. I also think her writing was beautiful but more accessible than some books we’ve read in the past.

Marvellous article. And what about Jenny Diski’s Skating to Antarctica and Doris Lessing’s autobiography Under My Skin/Walking in the Shade, as well as the fictionalised account of Martha Quest and her visiting mother in The Four-Gated City? Devastating accounts of damage by mothers who were either emotionally damaged themselves, or vastly frustrated.

Feel free to add more suggestions.

Thanks; I’m not familiar with those, so I appreciate the feedback.

I would also add Jacqueline Walker’s ‘Pilgrim State’. A lesser known but beautiful account of the powerful bonds between mothers and daughters.

Thank you for suggesting these impressive books.

More? The Great Mother, A Very Easy Death, A Sicillian Romance (with a very interesting – from a psychological point of view – ending) and On Matricide.

I suggest:

The Lives of Girls and Women by Alice Munro

Pearl by Mary Gordon

Unless by Carol Shields

Offshore by Penelope Fitzgerald

Why be Happy When You Could be Normal? by Jeannette Winterson

A fascinating slant on mother-daughter reads.

I would add Elfriede Jelinek’s The Piano Teacher to this list of great books. It’s such an intense, claustrophobic study destructive co-dependency, and the language so beautifully conveys the subject matter.

Yes, Jelinek’s Piano Teacher is interesting but I don’t find the book inspiring. I think Jelinek starts from a premise that I don’t share – not only in The Piano Teacher but also in her other books. Her view of men (as opposed to women) is very dark, almost as if ‘man’ and ‘patriarchy’ are the enemies and women yet again are the mere victims. I am much more interested how I as a woman can change my thinking in order to make use of the freedoms that we have achieved in Western societies in the last 100 years and then use that as a springboard to effect a little shift or new understanding – however small that may be.

Ack… Little Women. The book leaves you feeling both happy and sad, for Beth, I think it’s the best that can be said about a book that is capable of taking you from one sensation to another through reading, as this means that the novel has managed to get involved in it so you feel what you want to convey.

Although the strongest values of the same are overcome, ever do something for those who are worse than you, that bad you are you there are people who are worse off, and do it in a human way, that is not because yes, but sometimes revealing to against that condition you have, and protesting, which makes sense in girls aged 12 to 18 years.

I like the way that trace the four main characters, the four sisters, each with its peculiarities, each with their own desires of age, but all a pineapple, among themselves and with their mother, woman that try to look like and does everything possible for their education as they mature as time goes by in a situation of war and women older sisters really nothing more than little women, maybe that’s the best of the book.

Ultimately I think it’s a novel that must be read, from which we must draw many positive attitudes towards life and that certainly enjoy reading.

Great piece, really fascinating topic. The question I have about Little Women (a book I adored as a child) is: what is the book each of the girls is given by their mother on Christmas Day? When I first read it as a young child I assumed it was Pilgrim’s Progress, though that seemed strange – but it was the book they’d been discussing. Then, later, I thought it must have been the Bible, or a New Testament, which would seem more likely and to make more sense. But then I read somewhere that Pilgrim’s Progress was an unbelievably popular book in the New England of the time (far more so than in the UK) – so maybe it was that? Can anyone settle the question for me?

I always thought it was Pilgrim’s Progress too, but maybe I’m wrong?

Loved this exploration of mother-daughter relationships in literature! I feel like it is often an overlooked relationship, despite its complexity and primal nature. Your article has inspired me to check out The Bean Trees as well, which I had never heard of before. Great job, Stephanie! 🙂

Have you heard of Rebecca Solnit’s non-fiction work The FarAway Nearby which provides an interesting insight on a particular type of mother-daughter relationship and how it changes as she descends into the grip of Alzheimers Disease, equally fascinating to listen to her speak on it.

No, but it sounds good!

I read Little Women when I was 12 or so and afterwards all of Alcott’s books for girls. I am quite certain that Jo continued to write and publish during her lifetime and chose her husband for his amiability and sense. And perhaps as something of a replacement for an often distant father? I never thought of the book as particularly moralistic or sentimental, only as faithful to the sentiments of its times, and not as maudlin as some works of the same vintage. I believe its strength lies in its three-dimensional characterization of four very different sisters in their struggles with the ups and downs of everyday life in a New England town in the mid-19th century. It’s not a polemic. It’s a deliberately mundane reflection of the way people are. It would be fun to place these characters in our century and see what they make of it, but that would be a new story. I bet though that there would still be fights among sisters and times when people wished they had just shut their mouths and not made a mess of things and so forth and so forth.

The best version of Marmee was the recent PBS version, with Emily Watson as Marmee. She’s clearly at her limits, but always pushes to be there for her kids. In that version, she’s crying in her room for Beth, but has to visibly swallow her grief to comfort her remaining children when they walk in unexpectedly. I hadn’t realized how much, as an adult, I needed a human Marmee, visibly struggling to keep it together yet be there for kids. A Marmee who is just barely keeping the household together some mornings, yet still noticing that a kid needs a moment. The girls in that version – meh, but Marmee, yes.

I’ll have to rewatch that one!

I would also like to be Marmee to my five kids – three of which are boys 😀 They are teens and we have a good relationship.

I am a huge fan of both stories about mother and daughter relationships as well as stories about the Asian immigrant and Asian-America experience. The Joy Luck Club delivers on both.

I found it incredibly fascinating to see the differences and similarities between the mothers and their daughters. I also loved reading about the mothers as children growing up in China and then seeing them as mothers of their own in their daughters’ stories.

The friendship of the women and their daughters, the struggles to impart the Chinese culture to their American born daughters, and the difficulty the daughters felt trying to assimilate American values with their mothers’ more old fashioned Chinese views are very relatable to me, which is probably why I like stories about these topics.

Amy Tan’s writing style really drawls you in and she does a fantastic job of establishing voices for all eight characters!

The mother/daughter relationship in The Joy Luck Club is so incredibly intense, no matter who you are; I don’t know why, but it is. It doesn’t matter that these women are Chinese in an era from which I’m at least a generation removed–I heard my own frustrations in the daughters, saw my mother’s confusion with me, felt the love of both sides as we deal with being in totally different spaces. The stories of these women shocked me, angered me, saddened me, made me smile, and were just totally, utterly human. Usually I’m not a huge fan of simple human stories, but this…this is a gem, truly, that I will hang on to. Some day, perhaps, I’ll give it to my niece–when she’s old enough to be frustrated with her mother, but to realize that the woman I knew wasn’t always that person. Generations need to look out for each other like that.

“Totally, utterly human.” Yes, that’s definitely the way I’d describe JLC and the characters in it. I think too, that being in different spaces than the characters lends us some much-needed perspectives. I wish more teachers required JLC and books like it as part of their curricula. We’ve come a long way, but the perspective our students get is still overwhelmingly Western, white, and male.

I read Bean Trees for the first time when I was in high school… Reading it again over 20 years later was such a treat… Like having coffee with an old friend

I loved in 20 years ago in high school, partially because of how important a book it was in my reading relationship with my mom, and partially because it’s just a great book.

It was interesting to see how some aspects of the book impact me a lot more now, especially since i’m a parent and it was fun to see how this is a another good example of the (to me) very important “people treating people like people and being kind” genre of books. Life is hard, bad things happen, institutions and countries casually crush lives and families. Fight how you can, but make sure you have a family (of blood and/or choice) to support and help support you.

Joyluck is a book with a great deal of struggle and dissatisfaction, always hinting at the power of motherhood as a form of redemption. Thanks for covering it.

The relationships between all the Mothers and daughters was so sad to me in Joy Luck Club. The daughters couldn’t appreciate what the Mother’s had been thru and why they were the way they were and acted they way they did. The daughters were also in a lose/lose situation because as much as they wanted to be American they were caught in the middle of two cultures. Not fully American nor Chinese. At home or with family, life was one way but at school and later at work, another way. I can’t even imagine being a newcomer to a country and trying to instill customs & values from the “home” country. It seems impossible to keep continuity going?? Especially with so much resistance from the 2nd generation (in this case the daughters.) We witnessed that frustration (it felt more like a disconnect from each other??) although there was some hope that the older the daughters got, the more willingness they had to try & understand their Mothers.

I LOVE Little Women, and I love rereading classics with my children! I read them so differently as a parent. My husband might be a little tired of hearing me talk about how much I admire the parent in the Little House books (and others!)

I have never read these books 🙁 I love this post! Great examples to incorporate into my life as a mom!

I enjoyed LW as a child but read it more recently for my book group and we were all surprised at how badly it had aged (or we had, not sure which).

Yeah, I wouldn’t say it has aged well. For instance, I’m not a fan of how Beth is almost completely perfect, or the fact that she has to die to “make room for” stronger women like Jo and Amy. But then again, can we fault Alcott for writing with a 19th-century audience in mind? That’s why I think it’s a great idea to read modern adaptations or modern books with similar themes alongside any classic.

The Bean Trees makes me appreciate life and become grateful for what I have.

I started to read Amy Tan’s book as a novel initially and tried to keep up with the relationship trees between the moms and daughters of the Joyluck club. However, I was quiet unsuccessful and had more success with reading this and individual stories slightly interconnected and just focusing on each of these women’s experiences and how they differed from each other although they were all Chinese immigrant experiences. Insightful and engaging for sure. Little Women is my next stop.

No other writers could provide a clear account of a mother-daughter relationship in a Chinese-American family.

i used to swear that i was a “jo” in my youth but in reality i have come to accept i am a “meg.” i love being at home and taking care of my girls. i spend much of my time reading and brainstorming on how all of us in our home can create habits of growth spiritually, physically and mentally.

You sound like me. Maybe we’re both Megs. And since I am an oldest child, I’d say I’m probably a Meg regardless.

Years ago my friend’s mum said that she read the Little Women books when she was about twelve, the age her daughter was at the time, and she said she tried rereading them as an adult and she didn’t know what she saw in them.

Little Women is one of those books I think I read when I was a little too old (late teens) for it. I have never seen the appeal.

The author, Louisa May Alcott, hated the novel herself. She called it “dull” and an exercise in “providing moral pap for the young,” and I dare say she is right on both counts.

I see what you mean. I think that whether readers think Little Women is dull and moral pap, is up to who you ask. In Louisa’s case, I think she was unjustly cheated out of writing what and how she wanted to write, because of her time period. It’s one thing to write because you love it, but when you must do it to provide for yourself and your family, there’s definitely a sense of pressure and forcing yourself to do what other people want. I say that as a person who writes what she loves for fun, but has throughout her life been told, basically, “You can’t do that. If you want to get anywhere, you have to do what others tell you, and that includes writing what they tell you.”

I don’t think she hated it quite as much as people are saying; it’s been a while so I don’t remember quotes, but from reading her biography I felt more of a sense of ambivalence. I think she was proud to have written something good for children, and she identified with the work to the point that she often referred to herself as Jo.

I love Little Women version with Winona Ryder so I assumed I’d love the book.. YIKES. I can see why many like it, but it just didn’t do it for me.

I like it, but I think a lot of my positive feelings are nostalgic. It was one of my mom’s favorite books, and one of the first “classics” I read (one of those abridged hardbacks for kids, with pictures, a white cover, and red title. Can’t remember the imprint; if anyone can help me out, please do). I think we’re so far removed from the language and mindsets of “classic” books that the confusion and boredom can get in the way, unless they’re taught well. I say that as a teacher who doubted her ability to teach classics well, and who now questions the value of the “traditional Western canon.”

Marmee is best when not a Super Mom. Even as an adult and mother, I still don’t like Susan Sarandon’s Marmee. Too perfect, to giving, even with her husband away.

Susan Sarandon was the first version of Marmee I saw in film (the 1994 version came out when I was eight), so I didn’t have what you’d call an adult, well-formed opinion of her. I remember liking her better than Mary Astor’s Marmee because she was more “modern” and reminded me more of my own mother. I’ll probably always have a sense of nostalgia toward Susan’s version. That said, I can definitely see why you’d think that version of her, and Marmee as a character, was too perfect. Sometimes, throughout all versions of LW, it feels like Marmee is telling her daughters it’s okay to be human and imperfect. Yet, at the same time, she pushes them to do and be things they can’t, to varying degrees.

We can learn a lot from Marmee. I read the book as a child and have re-read it many times since.

Amy Tan is so insightful and has such a powerful and graceful voice – it’s like I could see the strokes of her pen, writing with conviction and love.

When I first started reading The Bean Trees, I wasn’t exactly sure what to make of it. In some ways, I thought it was hokey (it reminded me of that movie Where the Heart Is). But as the story develops and as Kingsolver’s unique writing style drew me in, I became unknowingly invested in everything. It’s hard for me to not use the word “magical” to describe this novel.

Call it “magical” if you like; some novels are exactly that. And yes, there is a sense of kinship with Where the Heart Is. I think though, that Barbara Kingsolver took a much more unexpected and thought-provoking route with her story. That is, we see Novalee Nation living in a Wal-Mart and having a baby, and we’re meant to think, “This is not normal or ideal.” We see Taylor taking on Turtle with no experience, and while we may think, “What on earth is going on,” it feels like Kingsolver also wants us to think, “Okay, this is what people have to do sometimes. This is an informed choice, and we can support it more as the story progresses.” At least, that’s what I remember as far as the two books.

Barbara’s descriptive writing is on par with Anne Rice. I felt transported.

I loved Little Women as a child and am reading it to my 11-year-old son and 10-year-old daughter now. They’re both really enjoying it. My daughter Josie (a definite Jo!) even dressed up as Beth for favorite book character day at school. TI greatly admire Marmee as I read this book as an adult and mother.

In Little Women, Marmee has a very special relationship with her daughters. She is the moral center of the family, she guides them with love, and she grooms her daughters to be good wives and mother’s. Through Marmee, the girls learn that in any relationship, love and trust are priceless above all else. She teaches by example.

I love Little Women and I’ve read it so many times.

Considering that Little Women was written in 1849, it is incredibly prescient about the personal, social and societal issues that were grist to her engaging and entertaining mill.

A remarkable author and human being.

I think I’ve always identified the most closely with Meg – maybe because I’m also the oldest of four children!

I have loved the exploration of mother-daughter relationships over the years, both within film and literature. Though this article seemed to mostly cover literature, I think it would be fun to explore thee similarities between Little Women and Greta Gerwig’s first film Lady Bird. Gerwig has often stated that the mother-daughter relationship is “the central love story” of the film, which I think shows as well in her adaption of Little Women. I just love the representation of these complicated relationships. I will have to add The Joy Luck Club to my list!

The portrayal of positive mother-daughter relationships is literature is necessary to provide a counter-argument to popular media that demonises the mother who, more often than not, only wants the best for her daughter. Brilliant article that touches on important concepts and recommends some splendid reads.

“[The mother-daughter relationship] has touched and continues to touch mothers and daughters across the centuries.”

That I think is a good summary of the appeal of this kind of story (its relatability and timelessness) and its durability.

I find that with novels and film adaptations such as Little Women, it resurfaces a space for generations of women to come together and talk about what it means to ‘grow up.’ One scene in the Greta Gerwig adaptation that I love is when Jo and Marmee sit on the floor and talk about how they struggle with their anger, with Marmee saying ‘I’m angry nearly every day of my life.’ Seeing this other side of Marmee compared to previous depictions of her being supermom, to me humanizes her which connects to the moment growing up when you realize that your parents are not perfect.

I would also add that the series Gilmore Girls definitely falls into the mother-daughter genre. Not just between the main characters Rory and Lorelai but also between Lorelai and her mother Emily.