Story or Style: Which Should Directors Concentrate On?

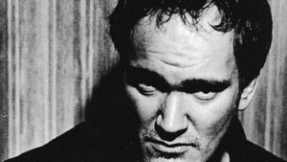

At the time of this writing, a number of notable directors are at various stages in production on their next pictures. Christopher Nolan’s ninth film Interstellar is set to be released November 7th of this year, while on the other end of the filmmaking spectrum, Quentin Tarantino has begun pre-production on his next picture, The Hateful Eight (coincidentally his eighth feature). What these two filmmakers have in common – as well as other filmmakers like Wes Anderson, David Fincher, and Darren Aronofsky – is that their oeuvres are miniscule in comparison to many of the great filmmakers from both the New Hollywood and Golden Age generations.

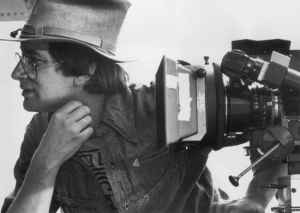

Steven Spielberg is working on his twenty-eighth film, a thriller titled St. James Place, while Martin Scorsese is finally getting set to direct his long awaited adaptation of Shūsaku Endō’s novel Silence, which also happens to be his twenty-fourth feature. If you think that’s a lot of movies, you ain’t seen nothing yet. Akira Kurosawa directed thirty-one films, Alfred Hitchchock directed fifty-four, and John Ford directed well over a hundred. The point here is both simple and hard to understand; from a historical aspect, one can easily note that most modern directors are making less movies. From an artistic standpoint, however, it is difficult to understand why director’s are making less movies. It certainly isn’t from lack of passion or talent, so could it be that contemporary filmmakers are placing limits on the amount of movies they make?

It is best to pause and realize that there could be other reasons that directors are making less movies other than caring about their personal filmographies. One of the biggest is the problem of studio interference that has lead so many filmmakers to migrate to the world of TV programming. Steven Soderbergh, Gus Van Sant, and Michael Mann have all dabbled in TV and in Soderbergh’s case, he has found a measure of success with Cinemax’s The Knick. What is important to note is that these directors didn’t start working on TV just because they wanted to try something new. The underlying reason was that they were being pressured to make films that didn’t align with what they were envisioning. In Soderbergh’s own words, director’s are treated “badly” by those who finance most films and that in turn leads to directors wanting to find an outlet that will allow them to tell the stories they want in the way they want. This is a spot of bother that even titans of cinema like Spielberg, who one would think could make his own movies whenever he wants and however he wants, can’t escape from. At USC last year he proclaimed that his 2012 biopic Lincoln almost aired on HBO, and the only reason it didn’t was he co-owned the studio that released it. Needless to say, this is a pressing problem that will only be worse for directors who have yet to really cut their teeth in the world of cinema.

But as bad as some directors are treated, it still cannot account for the amount of popular filmmakers who, at times, go for years without releasing a new picture. It’s an odd occurrence and one that cannot be simply chalked up to business problems. Instead, it could be that directors nowadays focus more on their craft and particular style of filmmaking rather than on the stories they are telling, and to that effect are worried that they will lose their touch over time should they make more movies.

This could be referred to as “Tarantino’s Curse”, which is the theory that as a director’s career goes on, they tend to lose their finesse, sometimes to the point where they end their careers with a set of four or five really bad movies that eclipse the director’s earlier work. Tarantino is being unjust when he says that a couple bad movies can overshadow a director’s entire career, but one can’t help but see that there are some directors who have lost the skill that they were once lauded for. Tarantino cited Hitchcock as a victim of this curse, but there are many other notable directors who seem to be suffering from it as well. Francis Ford Coppola, who helmed four magnificent pictures in the 70s, has since slipped into obscurity with movies like Twixt and Tetro. George Lucas has long since stopped making films, and isn’t even in control of the next set of Star Wars pictures. And even Ridley Scott, who managed to bring back the sword and sandal epic (briefly) in the 00s, has had four back-to-back movies that failed to make a profit (Body of Lies, Robin Hood, Prometheus, and The Counselor). Meanwhile, directors like Tarantino and Nolan sit comfortably on a set of eight or nine great films that haven’t received a fraction of the criticism that has been directed at the aforementioned filmmakers.

But then how do we account for directors like Spielberg and Scorsese who are still going strong? The reason may be that they and directors like them tend to concentrate more on telling a story than on creating a recognizable technique. Spielberg articulates this very well when he calls himself a storyteller and a craftsman rather than a stylist. He is “style-less” and is able to adapt himself to the story that the screenwriter is telling, and because of this, he can seamlessly jump between genres. He can make a tragic drama about the Holocaust as easily as he can make an action fueled romp.

Scorsese is even more unique as he is one of the handful of directors -along with Stanley Kubrick and the Coen Brothers- who has managed to produce an eclectic filmography and create a recognizable cinematic style. While he is most often associated with the crime genre, Scorsese has also made spiritual dramas (The Last Temptation of Christ, Kundun), romantic dramas (Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, The Age of Innocence), historical epics (Gangs of New York, The Aviator), and even an absurdest comedy (After Hours). None of these films, or for that matter any of the films in his oeuvre, feel repetitious. It truly is a testament to Scorsese’s storytelling acumen that he has managed to tell such a broad range of stories while always providing the cinematic flair that he’s come to be known for.

This is something that cannot be said about directors with smaller oeuvres who focus more on refining their personal style than on telling a story. Can Tarantino make a sci-fi drama? Can Nolan make a romantic comedy? Can Wes Anderson make a high-octane action movie? The answer is “no” across the board. That doesn’t mean they aren’t allowed to try, it just means that their particular styles don’t allow them to branch off easily from the stories they’re used to telling. Tarantino is synonymous with action oriented revenge pictures, Nolan with intense psychological dramas, and Anderson with quirky screwball comedies. While they play their respective notes beautifully, they don’t pay much attention to the other keys, and since they’ve found success in the way they tell their stories, there’s no need to alter the stories they tell. It should also come as no surprise that most directors who have created their own style also write the scripts for their movies so as to remove any possible source of creative conflict. In essence, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

This is a muddy subject to talk about because there are many good arguments on both sides. It’s not only harsh to accuse Tarantino and Nolan of being mundane, it is also completely untrue. And though they almost have thirty movies under their belts, Spielberg and Scorsese have revisited similar themes throughout their respective careers. But take a step back, and you’ll realize there is a bit of an exchange that occurs depending on what a director chooses to do with their career. Should they choose to focus on their skills and hone them to the point where they make films that are unmistakably their own, chances are they will only make a handful of movies. If, however, they are more interested in acclimating their skills in accordance to what a particular story demands, then there will be many more opportunities to make movies, though they may get lost in the hundreds of thousands of other movies that have come before them. So, is it better to have a brand or to have a lot of product? I hate to be anticlimactic, but I think it’s best to have a mix of both. The passion behind the filmmakers mentioned in this article is palpable in every movie they make, and ultimately it is that passion that becomes their cinematic signature. It doesn’t matter if they make five or fifty movies, or if they are remembered for reinventing a particular camera angle. As long as there is love at their core, the longevity of the movies they make will be ensured.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Filmmakers need to focus more on story, less on technology and everything else…

You bring up a good point about the technology that is so often employed in movies. CGI and 3D are huge now, but the problem is that it’s all spectacle with no substance. By using those technologies as a selling point in and of themselves, filmmaker are putting their stories in the backseat, when it really ought to be the other way around.

There was a joke about this on 30 Rock. Liz Lemon runs into a movie poster for Transformers 5: Planet of the Earth. On the bottom it says “written by no one.”

That’s pretty good 🙂

Well, movies, I think it’s time we accepted that it just isn’t working between us anymore. I’m moving out.

You were great fun when I was growing up, but these days you’re just a bit… well, childish. And expensive. And really quite repetitive. And dang it all, you’re so LOUD.

You used to take a few risks, remember? And sometimes you were a bit crazy, a bit unpredictable. Sometimes you made me think. You even made cry form time to time. And sometimes you were just a blast to be around.

But these days? It just ain’t happening. The fire’s gone out. Sorry, sweetie.

Great comment.

Sorry for your loss.

A lamentation that is felt by many, but take heart, there are still dedicated filmmakers out there. Thanks for the comment.

Story is everything.

I agree. Thanks for the comment.

We need movies that take us away from all this death and destruction of our times. Give us a movie that makes you happy in the end and people will come back to the theater. We have been sad for too many reason and for far to long to spend money just to feel worse in the end.

You have that in Rom Com’s.

Sadness is an emotion that seems to last longer than happiness, especially in film. Let’s be honest, how may of us go to movies to feel better about ourselves or because we want to hope the movie inspires change in the world? Most of us go for pure entertainment.

I’d lean towards sentimentality as well. Though it is important for storytellers to realistically portray the tragic things in life, they should also be brave enough to take the next step forward and offer hope. A lot of people spurn positive emotions in movies because they think it’s cowardly or because it doesn’t show how “the world really is” ( I think of all the criticism directed at Saving Private Ryan and Schindler’s List), but I think those movies are brave for showing the human capacity for regeneration and hope. If anything, it’s courageous for a movie nowadays to provide a message of hope, and it’s sad that more filmmakers don’t do so. Thanks for the comment.

We need filmmakers for a generation who know the form of everything and the content of nothing.

If you are calling for a wave of filmmakers that will concentrate more on story and the human aspects of storytelling for a generation who cares more about style than substance, then I’m in total agreement. Thanks for the comment.

I have to say that a good story has to be the genesis of any film. No matter how good something looks (this applies to things beyond just movies…e.g. food, clothing, etc.), if it doesn’t have substance, then it fails to reach its full potential. It may still LOOK good and have some value to it, but it never becomes as good as it can be. A unique visual style needs to propel a good story in order to be fully maximized.

Another director who has an amazing style that I love (and who has a new film this very week) is David Fincher. His dark, gritty style highlights and punctuates the powerful stories that drive his films. Se7en, Zodiac, The Social Network, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, Fight Club…all of these films have a strong foundation…courtesy of a good story to tell.

I’ll stop now before I write my own essay in the comments section haha. But great article. Great topic for further discussion; I enjoyed this greatly. Terrific work.

That’s an excellent observation Giovanni. If the film itself demands a particular style, then it ought to implemented in order to elicit a certain response from the audience. Fincher is excellent at this, and I would add that Darren Aronofsky is also a good example. Requiem for a Dream has many editing flourishes (e.g. the quick cuts, speed up and slowed down time) that are meant to make the audience feel as though they’ve stepped into the mind of a drug addict. In that sense, all those flourishes were not only necessary, but made the film great. There are, however, a number of directors who use such techniques only for show and not for substance (I think of Michael Bay and some of Oliver Stone’s work). Thanks for your comment and kind words Giovanni, I really appreciate them.

Sometimes, I look at a director’s filmography and think “GREAT! They only have 7 films – I can manage to watch all of them!”. But it’s true that there’s a downside to this as well. Sometimes, digging into a prolific director’s filmography can be so much more interesting than a style-heavy contemporary ones. There are a lot of small gems to discover and a lot of different stories out there. It’s not “just” a certain kind of film that gets perfectioned as the director moves on. That being said, I don’t think that unprolific directors get boring with time, for example I like Wes Anderson’s newest films more than his older ones.

I’m a bit split because I think it depends on the director. I’m in agreement with Wes Anderson, and I would also add Christopher Nolan. Tarantino, however, has been stuck making action flicks for the past decade. And don’t get me wrong, I think his films are a blast (I feel I’m in the minority when I say that Death Proof was better than Planet Terror), but they are all about people getting even. In that sense, there’s no variety and each film seems like the last one in the sense that it’s just another revenge movie. Hopefully The Hateful Eight will change things up a bit and based on the synopsis, it does sound like it’ll diverge from his usual kind of story. I appreciate your comment Mette.

It’s so sad to see how many brave, smart movies came out of the late 60s and the 70s. Even the 80s at least had some fun action flicks, alongside some really good thought-provoking films. The 90s were very hit and miss, a lot of disney dross and action movies that might have been good had they been released in the 80s, alongside some great thrillers (se7en) and my personal favorite (Fight Club). But from the millenium on, the proportion of dogshit to films worth seeing has gone astronomically out of balance. Leading directors need to focus on creating a balance between style and story. A perfect balance.

But a balance that is hard to achieve. I agree mostly with what Giovanni said earlier; if a particular story demands a certain style, then it ought to be implemented. This is what accounts for Spielberg’s success; he doesn’t implement a certain style to his movies but rather adapts to what the movie demands, that is why he turns out movies that are so radically different from one another (e.g. Jurassic Park, Munich, Lincoln).

On the plus side, there are still many directors out there who are making emotionally and intellectually dense pictures. Here’s a list of the movies we can expect from October to January: Gone Girl, Fury, Nightcrawler, Interstellar, The Imitation Game, The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies, Exodus: Gods and Kings, The Interview, Inherent Vice, and American Sniper.

Some are blockbuster-esque (Exodus, The Hobbit) and one’s a comedy (The Interview) but aside from the peccadillos that are associated with those films, this seems to be a fairly good line up of movies. It’s just a matter of having to wait in between the summer and winter seasons where we tend to see a dry spell.

The implosion of the film industry is an appealing thought, perhaps leading to less transformer movies and a new golden age of film making. Probably not though.

Who knows; if expensive movies keep tanking, the studios that financed them may experience irreparable damage. Disney is still reeling from The Lone Ranger which cost $250,000,000 and only made $90,000,000 while this year Noah cost $125,000,000 and only made $101,000,000. This is a shame as I enjoyed both films, but my opinion doesn’t count in terms of business. Should this trend continue to occur, which is to say should movies that cost $100,000,000+ to make keep losing money, we could very well see an implosion. But it’s at this point that I’d cite William Goldman’s dictum: Nobody knows anything. Thanks for the comment.

When it comes down to it, the only criteria that really works for me is that it is a person who consistently makes great (or for me, at least, interesting) films. I figure if a director is responsible for the final product, then the final product dictates his adeptness. A filmmaker who makes great films is a great filmmaker, and one who’s films are overwhelmingly mediocre is a mediocre filmmaker. It’s perhaps simplistic, but it makes the most sense I think.

I like to call that Nolan’s Rule, which is that the only time he feels like he’s wasted his time at the movie is when there’s no passion involved in the film itself, in other words when he sees a lifeless movie. I’m in agreement with him and by extension you Eric; if there’s some pulse to the movie that is available in most of the director’s other films, then I’ll tend to enjoy that director’s work as a whole. Thanks for the comment.

I can appreciate style, but it has the potential to miss the mark and become slightly gimmicky – style over substance, if you will. So, here I am, kindly asking that directors realise the importance of storytelling.

I’m in agreement Jessica. Thanks for the comment.

The greatest directors should always focus on the subtext, not the test. If that says anything.

It certainly does; that’s a great way to put it Zetta. Thanks for the comment.

I think it depends on the approach. If the director has a strong story in mind, then that director should figure out a means of telling that story with a specific style or approach that both hails to their previous works and can be something new.

At the same time, let’s say that you want to do something abstract, like Michael Powell’s “Peeping Tom.” His was a very unique take on the horror genre that spoke through generations, and one that – from watching – could arguably have been conceived in form long before the story was thought up.

Haven’t seen any of Powell’s work yet, though I am very interested in it. I agree, as with Giovanni, that if a particular story demands some kind of stylistic edge then it makes perfect sense to have such a flourish included. Thanks for the comment Jemarc.

Some of my favorite movies are those from the 40s, 50s, and 60s. They had to depend on great acting and storytelling, not CGI, nudity, and gratuitous violence. Look at what director/writer John Hughes did; he told memorable and relateable stories, such as The Breakfast Club. It has one basic setting, few actors, but great dialogue.

Totally agree Liz. Some of my favorites include 12 Angry Men, On the Waterfront, Ben-Hur, Buster Keaton/Charlie Chaplin pictures, amongst others. There is a charm to the simplicity of these movies, but they can also be really dense and meaningful without having to resort to cheap tricks. Thanks for the comment.

I completely agree it is important to have a balance of brand and story. This article not only applies to filmmakers, but all types of careers. It is important in film and all other fields to build a brand by taking risks, and developing a repertoire with people with various skills and background as you create your brand.this Finding this balance will always create success.

That’s true. So often in sports nowadays, athletes become remembered because of a literal product or because of some kind of style that is personal to them, but they also have to be part of the team if they are to succeed. Thanks for the comment.

I think that story and style can influence each other. I think that in order to tell a great story a director needs to have a clear vision of how they want to go about it. And that’s where style comes in. Perhaps I’m naively advocating for a balance of the two, but it’s the work of up and coming directors like Ava Duvernay that give me hope for the film industry.

I hear you Helen. Thanks for the comment.

Interesting article. Personally, I think style and story are of almost equal importance, as the story is being told through the medium of film. That said, it is important that the film’s style reflects the story it is telling, as well. The Coen brothers are among my favorite directors because their style always seems to add extra meaning to the story; bringing for themes and ideas that aren’t explicitly in the text itself.

I’m with you. Like the Coen Brothers, I think other filmmakers like Darren Aronofsky are fond of creating styles suitable to the stories they tell. Thanks for the comment.

I think that in some directors’ cases, they just aren’t WILLING to do what it takes to get the supposed “riskier” films made. They sit on material for years and years and years just waiting for a major studio to finally agree to make it, when perhaps they could go to a smaller independent studio and make a better film. Yes, indie budgets are minuscule and the film is almost guaranteed to not make nearly as much money, but some directors are finding that the benefit of increased creative control over their projects is worth the financial cutbacks.

I think that the filmmaker who encapsulates this ideal the best is Richard Linklater. He’s made 16 feature films since 1991, more than twice as many as Tarantino has made in the same timeframe. Rather than sitting around waiting for someone to make his film, Linklater would rather take his ideas to any studio who will give him even a minimum budget and just do it. And the result is often spectacular: “Boyhood” and “Before Midnight” were both made for under $4 million. In fact, he hasn’t made a studio film since 2005’s “Bad News Bears,” and yet he seems to be doing just fine.

Part of that may have to do with the fact that some of the directors in question in this article – namely guys like Tarantino and Nolan – have developed styles that require studio-sized budgets to pull off, but I’m not sure if I’m willing to accept that as an excuse. With the number of filmmakers who are able to make truly great films with minimum budgets, and the number of big name stars who have shown that they are more than willing to lend their talents to independent films, there’s really no excuse for any filmmaker to not be able to make the film that they want to make.

Tyler, you make an excellent point when you say that the stories that some directors want to tell require much more money than directors who are known more for indie flicks. Linklater, I’ve heard, is a fine director, but all of his films are fairly subtle in nature. I hope I don’t sound like I’m dismissing his movies, but it stands to reason that it doesn’t take a lot of money to make a movie about a boy growing up (Boyhood) or a couple through the decades (Before Sunrise/Sunset/Midnight). But if you want to make a spectacle driven Western or a sci-fi heist film, you’re going to need a lot of money to make it. In this regard, I can understand why directors like Tarantino and Nolan take a lot of time making movies. Thanks for the comment Tyler.

Also consider that directors like Spielberg don’t actually do as much work as the more indie directors. I once read that Tim Burton was hardly even on the set of Nightmare Before Christmas. In cases like these, directors are more like project managers who delegate majority of the work to others. It’s no surprise that a unified style does not underly all of Spielberg’s films, because there are so many people contributing.

Now consider someone like Shane Carruth. He directs, writes the scripts, writes the music, and acts in his movies. If you’ve ever seen Primer or Upstream Color you would recognize a priority for style over story. I have no problem with that. Sure, I enjoy a good story, but when it comes to film I think style and aesthetics should be placed first. Otherwise, why not just film someone telling a story?

You’ve got a point about some director’s taking a literal seat while they make their movies. One need only watch the behind the scenes documentaries of the Star Wars Prequels to see that Lucas directed the majority of those films from his chair. But there are still director’s who are known for having a real hands on approach to their job, including Spielberg. In fact, there is a lot of debate as to who the “true” director of Poltergeist was seeing as how Spielberg, though only a producer, was on set directing so much of what happened, even though Tobe Hooper was the one who received the directing credit.

Still, it is important to note that there are directors who do much more outside of merely producing and directing their features. Your description of Carruth reminded me quite a bit of Chaplin, seeing as he too is one of the few filmmakers to write, direct, compose, and act in his movies. I even remember William Goldman once saying that Chaplin was the only person who could prove the auteur theory to be true. I’m glad you pointed out the distinction.

And a last note on aesthetics and story. I think that the story ought to take precedence and the style, if there is any, should be used to compliment the story. You say, “why not just film someone telling a story?” The first problem there is that a film is not meant to be a direct accounting of a story, it is meant to place you in the fray. Take Edge of Tomorrow for example; we would only be able to feel the frustration and anger and dark humor of the story by seeing it unfold, not by listening to somebody talk about it. In the end, the degree of separation that exists in merely telling someone about a story and actually watching it is a substantial one. In response to your question I’d ask, would you give up the movies if all you had to do was listen to someone else talk about them or read a synopsis on the internet?

The second thing I want to mention is that most documentaries are just as you described; they are films in which people talk and tell their stories. The Fog of War is a feature in which Robert McNamara talks about his time as Secretary of Defense, and it is more or less just him talking for about 90 minutes. But it is fascinating because it is real. This isn’t a fictional story nor an interpretation of a real one. This is a real, present moment documentation of a man’s thoughts and feelings. Again, the story that is being told dictates what the style should be like.

I appreciate your comment Tom.

I see your point, especially about documentaries, and maybe my initial question was too knee jerk. The more I think about it the less confident I feel about my preference to style. There are some movies that prioritize story and there are some that prioritize style. Maybe it’s just best to take it as it is! I can think of some plot-less movies that I like and some style-lacking movies that I enjoy as well.

Good thread! You’ve sparked a lot of discussion.

Thank you again for your kind words and, I want to reassure you that sometimes style is a thing to look for and appreciate when done well. I doubt that any of Terence Malick or David Lynch’s films would’ve packed the same emotional and psychological punch had they been presented in a traditional way. I love what you said Tom; “Take it as it is”. Indeed that as it should be with movies.

Well done on the article! Gave me a lot to think about it! Authorship does indeed refer to the director’s hold over a production to create a distinguishable work of art. With film, TV etc. relying on the screenplay/direction relationship, many directors make the choice to either pick scripts they are entirely comfortable with or writer their own. James Cameron, for example, takes up many years crafting every inch of his singular vision. Meanwhile, big-names like Ridley Scott take scripts and run with them (which may answer for his recent foibles).

That’s a good point Thomas. It could be that some directors just have to look for what they can get their hands on and don’t give enough thought to how they’re going to tell the story in a cinematic fashion.

Form follows function, thus, story precedes style. Now, in deference to some auteurs like Malick or Tarantino, it would seem contrary to this, however, with deep analysis, one sees the the story is always the root substance of all their “great” films, in spite of their visual aesthetics.

I agree. The Tree of Life, for example, though very abstract did have a sturdy theme underlying it, which was the eternal battle between nature and grace. Though at times it does get quite high-minded, the “story” never truly deviates from this theme, thus providing the audience with a definite moral. I would say though that Malick can be pretty hit or miss; the reason I disliked both The New World and To the Wonder was because it felt like he put too much of an emphasis on style with those movies, so much so that by the end I couldn’t see any definite meaning to them.

Very interesting article. I like all of these filmmakers and, in my opinion, stylistic filmmakers can still make great films as stories can still be strong in films of their chosen style. Anyways good article.

Thanks Tyler, I appreciate the kind words.

I am glad somebody has analysed this subject area. I have just completed an MA in Scriptwriting and part of the ‘business insight’ we are given regarding directors and filmmakers is that in some cases you can expect them to ruin your story in order to present a pretty picture. On the other hand, I am sure it is arguable in some cases too much attention is paid to the plot and therefore the spectacle is not what it should be. Ultimately their is a balance and it is up to the producers to ensure sufficient amount of budget is allocated to allowing both areas to co-exist and produce to best piece of entertainment possible. The way I see it, masterpieces come together when the two compliment one another. Film is a visual medium and that is to be respected, but people don’t go to the cinema to watch lots of pretty pictures one after the other: they go to feel something, which is the point of a story.

And please excuse by terrible use of ‘their’ instead of ‘there’ in the above comment!

My* – I really should proofread!! Anyway, good article!

Thanks Robbie, and no worries about the misspellings, happens to everyone you know. Having taken a couple of screenwriting courses myself, I know exactly what you mean when you talk about how the business angle of the movie industry makes it hard for writers to fully realize their vision. Like Nolan or Tarantino, they’d probably have to be the director as well if they wanted to make sure the movie was up to their standards. But as you later point out, the best directors (I’d again cite Spielberg and Scorsese) have managed to establish a good relationship with writers that has ensured their large bodies of work. Again, I appreciate the kind words and the great comment.

I loved the concept of this article, really cool idea. Personally I think that it’s the story, not the style, that is most important. Every director will have their own style regardless of if they are focusing on that style. Which makes me believe by focusing on the story the directors style will fall into place naturally.

Thanks for the kind words jcamp 🙂

It’s a mixture of both , look at Nolan The Dark Knight Rises . The tone match the story and have a realism feel. Another director Takashi Miike who made Ichi The Killer , Visitor Q and Gozu, they blended well with style and story.

True, the best films are usually the ones that can blend their form and substance seamlessly. Thanks for the comment ThirstyJack.

I believe that style and story are equals in the film medium. While the scale can dip in either direction, the discussion is highly contextual and can’t be measured simply by looking through “top-tier” directors. Films like Gasper Noe’s Enter The Void and Tarsem’s The Fall don’t concentrate highly on stories, but are visually unique enough to be considered reputable.

That’s the thing, I’m not sure if visual uniqueness is enough to buy me over. A film can be beautiful to look at but still dull. I’d say look at Terrence Malick; The Tree of Life is a splendid movie and I think it’s due in large part to his ability to visually represent the idea of the eternal struggle between Grace and Nature which is something best shown through visuals. To the Wonder, on the other hand, I thought was hopelessly boring because there wasn’t enough of a human element involved. It was far too poetic for it’s own good and ended up being more about the idea of love than the feeling of love. While there was a lot of potential there, it didn’t make much of an impression on me.

I’ve yet to see The Fall, though I want to very much and I haven’t seen Enter the Void though I have seen Irreversible, and though I don’t care much for the film (call me squeamish but I thought it a bit to violent), there is no denying that it did have a nightmarish quality that came out mostly through the camerawork and colors. And the story itself wasn’t bad either, it was just the imagery I found grotesque.

It’s nice to read this article. Yes, directors, like Wes Anderson and Tim Burton often will have a trademark. It would be nice to have filmmakers that can rotate around styles and forms, but we shouldn’t really hold it against these directors for having their own signature style. It’s as much as a disservice to reprimand a director, “stick with what you know!” as “why can’t you do something different.” They can be useful advice or recommendation for directors, but it shouldn’t be manifesto for a director’s choice. If we should criticize an overuse of style, perhaps we should aim those criticisms against the technique rather than the existence of style.

In some ways, how style works can depend on story, whether the director picks up a screenplay written by someone else (probably an adaptation of a source material) and/or when director handles the story during production. I think of the 2012 Anna Karenina directed by Joe Wright, screenplay by Tom Stoppard. Stoppard wrote the movie as a straightforward period piece, but would later approve of director Joe Wright’s idea to incorporate a modernistic stage fantasy element to the setting. The result got some mixed reception (I understood the criticisms but found it to be a fine piece of filmmaking and storytelling). Of course, there’s subjectivity to contend with. Some might find Wright’s addition to be distracting while some (such as I) found it as serviceable and characteristic for the interpretation of the story.

I appreciate your kind words and agree with your point about story influencing style. There are some films that, for some reason or another, seem to demand a stylistic twist. For example, Birdman had a fairly straight-forward story and was directed by a filmmaker who isn’t exactly known for having a specific style. Yet, the hallmark of that film is the cinematography, which makes the film appear as though it was done in a single take. While I don’t have any particular explanation, many have contended that it’s to make the film feel more like a play, since it is centered around one. Again, I’m not sure I’d subscribe to that theory, but it certainly does address the decision to film the movie in that particular manner.

With that said, I still prefer story to style since the first is more endearing to me. Again, thanks for your comment.

I would say that the focus should be on the story when first starting with the story. Once the draft is finished and the editing process begins, you can use stylistic conventions to refine the story.