Tehching Hsieh: The Experience of Time and Duration in Performance Art

Since the first Futurist manifesto in 1909, in which F. T. Marinetti layed out the main ideas behind the avant-garde art movement of Futurism, attention centred around performance practices and their derivatives started to accumulate. This tendency led to the establishment of performance art as a category of its own in the 1960s. 1 The remarkable thing this category enabled artists to do was to expand and examine the boundaries of practices that could be classified under its name. The possibilities were endless. One specific element, however, stands out – the question of time.

Time is an integral, ubiquitous part of every performance, regardless of its structure, which is often being taken for granted. Philosopher Henri Bergson lays out the idea of duration in time not as a felt phenomenon, but as a mental synthesis – an idea widely explored in the so-called durational or endurance art. 2 Often these performances are marked by some sort of transformation, a transition, an event, a happening or at least an end result, no matter how ephemeral it may appear. This can be either a change in the body achieved through an extended period of time or testing of one’s psychic endurance, or transformation of materials and so on. Amelia Groom defines time as ‘the most elusive of the seven fundamental physical quantities in the International System of Units’. 3 One artist in particular, the protagonist of this article, problematises this statement even further – his performances are not fundamentally characterised by the aforementioned traits, rather, his work exists in another realm, one that can only be understood on an intellectual level, similar to Bergson’s suggestion.

Tehching Hsieh

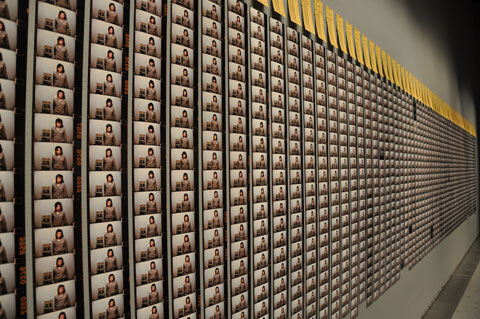

Tehching Hsieh is a Taiwanese-American performance artist best known for his One Year Performances in the late 1970s – 80s in America. On numerous occasions his work has been read mainly in relation to his own lived experiences as an illegal immigrant. This is in accordance with the genre of performance art’s assumptions, a genre which Jill Johnston phrases as ‘virtually defined by its bias for autobiographical source material’. 4 Meaning, subjectivity in art is something almost immediately read into the work of a given artist, sometimes without their intention or even willingness, and which from then on leads to the impletion of various socio-political, cultural and economic connotations. Despite of inevitably touching on such implications, one can try to extract them in a different light in accordance with Hsieh’s belief that there does not exist a singular, unique way of reading his artworks. Although they were made in a specific environment – New York in the last quarter of the twentieth century, Hsieh’s works can be positioned in a slightly more distinct context.

Critical attention can be turned towards an epistemological understanding of the concept of time, which in Hsieh’s words is ‘a notion of boundlessness’. 5 It is interesting to analyse how his work relates and differs to other performance practices, and to what degree can contemoprary audiences, as receivers of mere traces, claim to understand the work of Tehching Hsieh.

One Year Performances

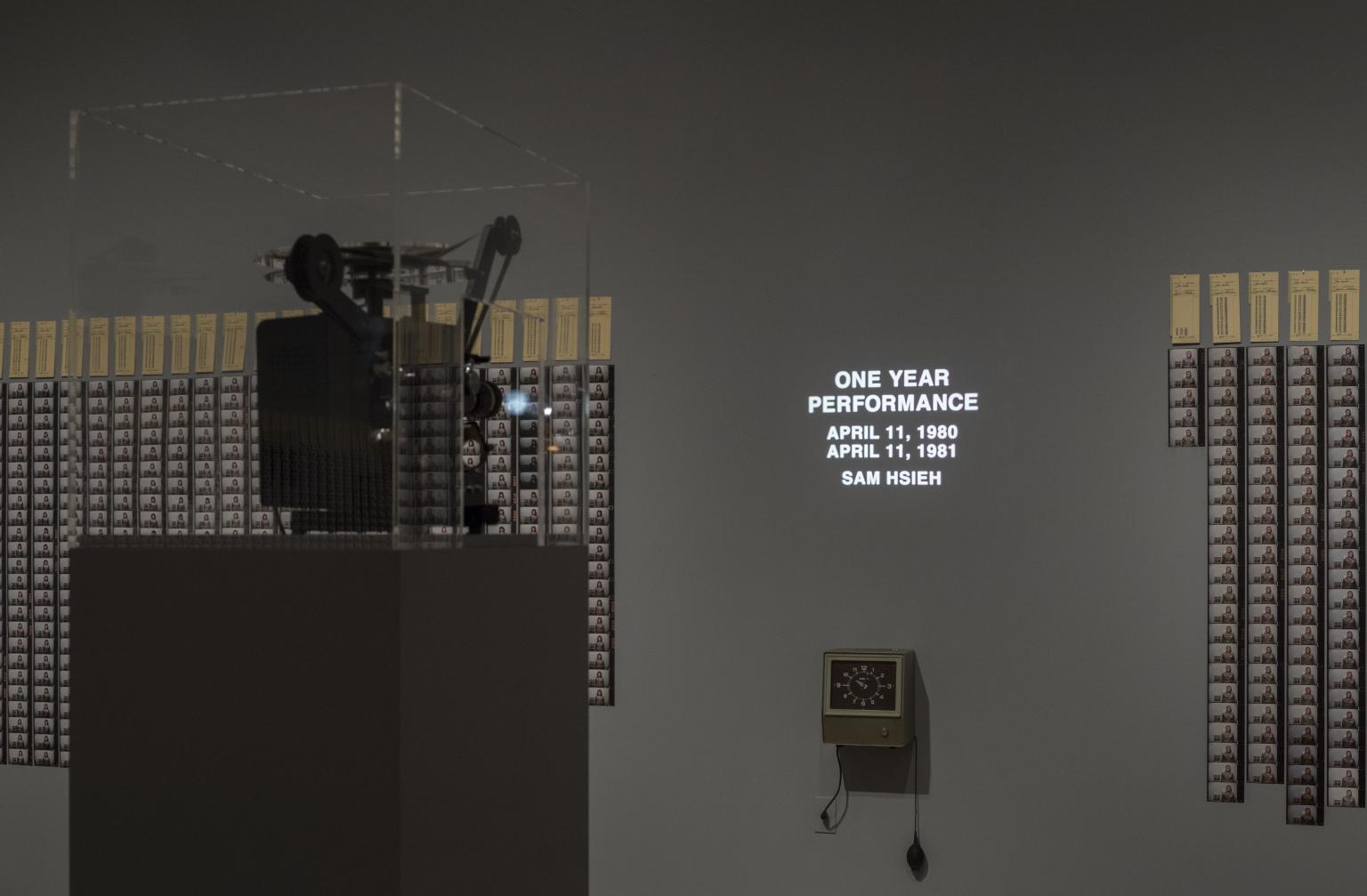

In order to capture the inherent complexity of his work, let’s focus our attention on emphasising the quality of time and duration in two of his works (which happen to be the first two) – One Year Performance 1978-79 and One Year Performance 1980-81, the informal titles of which are Cage Piece and Time Clock Piece respectively. 6 What stands out in these performances at first glance are the self- imposed limitations and their length, which altogether lead audiences and critics to make assumptions about the artist’s superhuman endurance. As much as this may be true, refraining from using the term endurance will guard the artist’s work against establishing incorrect associations with the rich, nevertheless somewhat distinct, field of endurance art practices. As already briefly mentioned, Hsieh’s work differs from these in its interrelatedness to time. He is not simply using it as a tool, or a medium, rather, he is being in time which enables him to embody and explore it on both physical and mental levels. The modes through which he achieves this are most evident and yet very different in those two pieces.

On the surface both works seem uneventful and enveloped by a sense of inertia. There is a lack of visible change or transformation of some sort, apart from the artist’s hair which he intentionally shaves in the beginning of each performance to mark the passing of material time as his hair grows back. Even if he performs some kind of action, it is only to be recognised as disturbingly futile and useless in and of itself. This tension between activity and passivity seems to be an underlying element in Hsieh’s performances. ‘Should we equate it with change’, Groom asks, ’or is time, as the quantum physicist Richard Feynman has quipped, “what happens when nothing else does”?’ 7 This question once more illustrates the paradoxical essence of the concept of time and hints towards another problem – the wasting of time.

In this sense, therefore, Hsieh’s work is rightfully positioned on the timeline of performance art in late 20th century, categorised as durational art, which tracks the development of industrialised societies and the accelerated capitalisation of the (art) market and therefore of individuals’ private time itself. However, his resistance to being assimilated with the political and cultural atmospheres of the time poses the question whether this is really the position his work should be placed and read in. ‘I was more interested in philosophical thinking’, he says in an interview, ’a way to develop myself, a way of asking myself, ‘’What does life mean to me?’’.’ 8 It might turn out that this is the best vantage point from which to examine his work at this moment, exactly forty four years after the beginning of his first One Year Performance, an era when our lives are becoming more and more digitalised and time is becoming an essential, yet restricted and limited, commodity.

Cage Piece

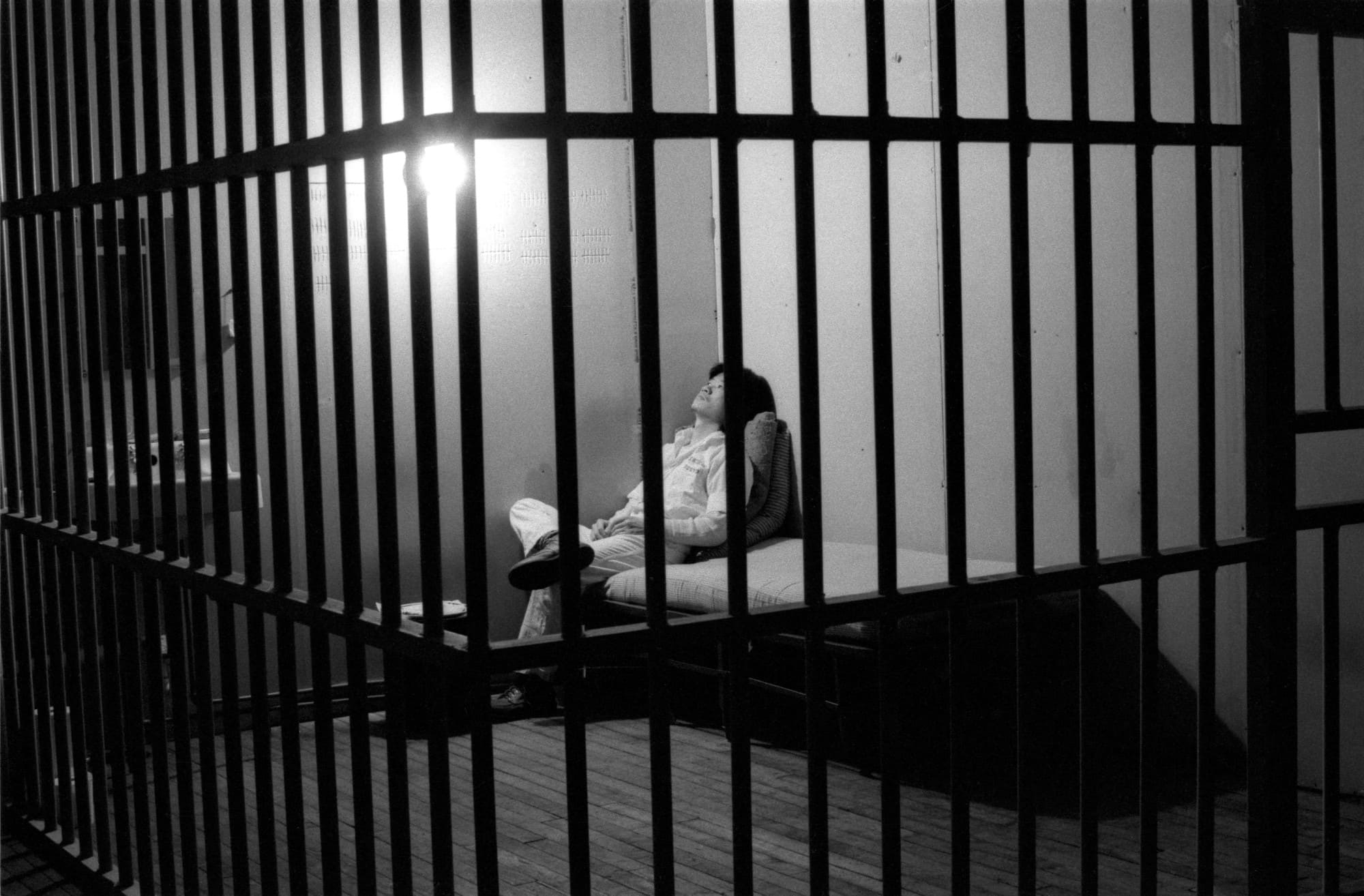

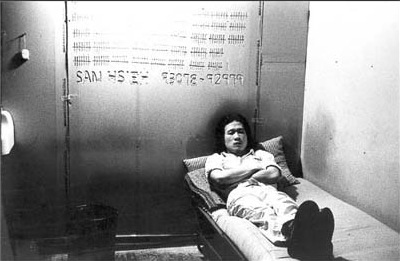

Cage Piece began on the last day of September 1978 with an opening statement that the artist will seal himself in a cell-room in his studio and shall not converse, read, write, listen to the radio or watch television until the end of the piece in September 1979. This ‘apparent aimlessness along with fine focus and rigor of execution’ is a quality that Thomas McEvilley ascribes to practices marked with a certain type of vow. 9 In Hsieh’s work those vows took the form of written declarations that he released prior to the beginning of each performance. Highlighting that Hsieh has ‘specialized in year-long vows acted out with great rigor’, McEvilley claims that among these performances Cage Piece was ‘done on the largest scale’. 10 During its period, every three weeks, the piece was opened to the public and audiences gathered in Hsieh’s studio to spend (waste) some time with him. He says that ‘the viewers didn’t need to come every day because every single day was almost the same.’ 11

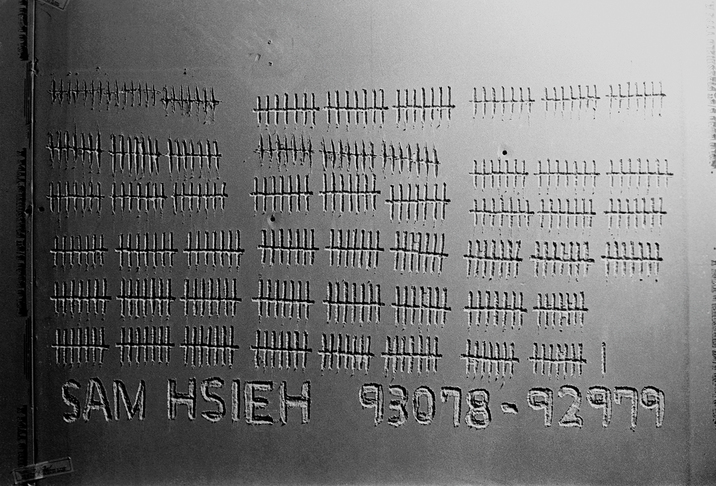

This is the prevalent effective quality of this piece – experiencing time as a monolithic whole, almost as if a simultaneous unit, every day being the same as the previous or the next one. In the outside world time was continuing its regular pace (whatever that may have been), but in the small cage the only indexes of the passing of time were the marks he scratched on the wall above his bed, the slow growth of his hair and the occasional daily visits from his friend and facilitator Cheng Wei Kuong. These mechanisms allowed him to detach any kind of socially constructed ideas of time from his experience.

Confining himself in a space and renouncing the social human’s basic abilities of speaking, reading and writing, he ‘forces’ himself to be in time, as opposed to passing this time intentionally by occupying himself with the completion of a task. One may think that the result of this undertaking is a sort of understanding of the notion of time from within its own constraints. By stripping his condition of life down to the sole activity of existing in time (apart from the basic human needs such as eating and defecating), Hsieh establishes a mode of being in which time is not seen as the unapologetic ruler of human existence, an inevitable, dominating phenomenon. Rather, his performance presents a conscious and willing giving into those powers which, paradoxically, grants him some agency over his experiences and an ability to manipulate the way in which he is inhabiting time and not vice versa.

Cage Piece is an unprecedented example of an idea put into practice – in a literal sense. The performance not only takes the form of being in time, but by doing so it also constructs the shape of thinking. The artist explains that this work ‘is not focusing on political imprisonment or on the self-cultivation of Zen retreats, but on freedom of thinking and on letting time go by’. 12 Even if such undertaking enabled Hsieh to practice ‘freethinking’, it nevertheless also caused him ‘an extreme mental struggle’ of having to constantly stimulate his imagination and will. 13 This, however, is a struggle known only to the artist to which we have limited access, if any.

It is evident, nonetheless, how this performance impacts the discussion on time in terms of its existential and ontological foundations. It gives the impression that time can be studied and explored by testing one’s own abilities and through using extended duration as a constructive element. Therefore, it could be said that Cage Piece deforms the linear travelling of time by undermining its ordinary inhabitation and by blurring the lines between a past-present-future moment into a single totality of existence.

Time Clock Piece

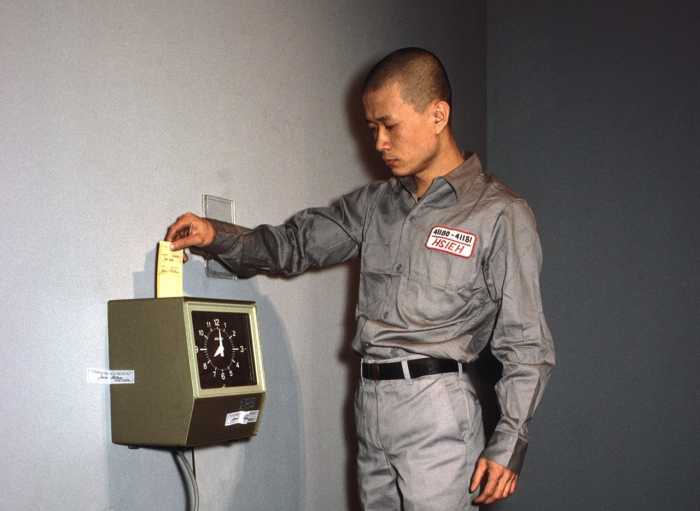

Tehching Hsieh’s second One Year Performance also cuts through the fabric of straightforward time but in a completely different way. As the artist says himself – ‘each piece has a different way in which it uses time’. 14 This distinction is expressed in the way he chose to tackle the unfolding of time – not as a unity, but as fragmented parts. Time Clock Piece began on the 11th of April 1980 at 7p.m. with the usual declaration of intent and finished on the 11th of April 1981 at 6p.m. In this piece, Hsieh punched a worker’s time clock in his studio every hour on the hour, day and night, for the entire duration of the year. From the 8, 760 possible punch-ins, only 133 he was unable to perform due to one of three reasons – sleep, being too late or being too early. These reasons were clearly indicated on the punch cards, signed by David Milne.

Due to the character of the piece and its evident performative strategies, Time Clock Piece often tends to be read in relation to capitalised labour and the socio-economical construction of time. It can also be seen as a critique of power relations within institutions and, as Adrian Heathfield suggests, it makes ‘the cultural rationalisation of time’ in late-capitalism explicit. 15

However, the quality of time examined in this article is not so much related with these readings, as it is with the idea of temporal disfigurement of the subject, executed by going in time differently. In this piece Hsieh is not so much physically restricted in space, as he is by time. McEvilley assimilates this practice with that of forest yogis in India where they used similar devices ‘to restrict their physical movements and thus their intentional horizons.’ 16 The main difference being the intention with which such devices were used in the two cases.

Time governs every human activity and function – from social organisation of time to biological effects of time in the human organism. Successful realisation of the performance entailed a limited amount of liberty in terms of how much time Hsieh spent on certain activities. Things like work, social contacts, leisure, travelling, were all governed by the ultimatum that he needs to be back in his studio to punch the clock on time. This would essentially enable a completely deformed experience of time, one that was divided into equal intervals and which therefore influenced all other aspects of his life.

at Tate Modern, London.

Unlike the Cage Piece, where time blended into one whole, here the artist is constantly reminded of portions of time and is obliged to follow its progression. The aspect of his life that was most significantly affected was, undoubtedly, his sleep. Being unable to acquire proper sleep is not only physically exhausting, but also mentally and emotionally draining. REM (rapid eye movement) sleep deprivation can lead to psychological disturbances, such as anxiety, irritability and even hallucinations. This decision, however, to punch the time clock for the whole duration of twenty-four hours a day, is an essential part of this piece, one reason is because when people sleep they have no conscious sense of the time, we are completely oblivious to it. And therefore this would be in discordance with Hsieh’s intention. Being in time, constantly feeling its effects in your body and being aware of its progression seem to be key ingredients of Hsieh’s investigation in the Time Clock Piece.

As George Kubler notes:

Time, like mind, is not knowable as such. We know time only indirectly by what happens in it, by observing change and permanence, by marking the succession of events among stable settings, and by noting the contrast of varying rates of change. 17

This remark is reminiscent of Bergson’s notion of time and indicates the way Hsieh uses his performance as a method of embodying this understanding and experience of time. By setting specific rules and dividing the duration of his everyday practices in such a way, he is suggesting a new mode of existence – one that dwells in time differently, one that perceives time not as a straightforward single timeline, but as ‘plenitude: heterogenous, informal and multi-faceted.’ 18

These two lifeworks by Hsieh seem to establish a sort of methodology for the reading of time which could help further analyses of its impact in performance art (and beyond). The specificities of these, as well as his other One Year Perfromance works, enables the spectator/reader to delve deeper into the notion of duration, which is also known as the ‘fourth dimension’. It is one of the phenomena that serve as the basis of life as we know it – a phenomenon which is theorised and yet never fully grasped. Hsieh’s practices allow for the study of this dimension and its effects through staging ‘an interruption of death’s, and therefore of life’s, usual mathematics.’ 19 This interruption is carried out in very distinct ways, which proves once again the heterogeneity of time and helps challenge and question duration’s mechanics which are pushed to the extreme and altered to a certain extent. Basing his work on his own will and strong internal regulations, Hsieh allows for the radicalisation of performance art practices, suggesting that all forms of life (and art) are possible and no single option is more (or less) meaningful than any other. Not unlike appropriation art, his practices represent a ‘shadowy recreation of the universe by drawing it, piece by piece, into the brackets of artistic contemplation.’ 20 His self – imposed regulations present the brackets of his practice through which he allows for the recreation of time in different shapes and within a specific durational frame. He also explains that his performances present his ‘different perspectives of thinking about life and art, but they are all under the same premise: life as a life sentence.’ 21

Cage Piece and Time Clock Piece examined two very distinct, yet very important, modes of inhabiting life. One was presenting time as formulating a single unity of existence, the second one realised it as a disruption, creating small, fragmentary units. Duration played a vital role in the realisation of such practices which fostered a fundamental understanding of notions of life and time. What Tehching Hsieh’s performances prove, therefore, is that duration is an inseparable force that shapes the very being of the life-art-time continuum and renders that continuum boundless and open as ‘it is possible for you to see it in many ways.’ 22

Works Cited

- For a more detailed history see RoseLee Goldberg, Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present, 3rd edition, (London, New York: Thames & Hudson, 2011). ↩

- See Henri Bergson, ‘The Multiplicity of Conscious States the Idea of Duration’ in Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness (Routledge, 2004). ↩

- Amelia Groom, Time: Documents of Contemporary Art (London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2013), p. 12. ↩

- Jill Johnston, ‘Tehching Hsieh: Art’s Willing Captive’, Art in America (22nd September 2010). <https://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/magazines/tehching-hsieh-arts-willing-captive/> [accessed 24 November 2018]. ↩

- Adrian Heathfield and Tehching Hsieh, Out of Now: The Life Works of Tehching Hsieh (Cambridge and London: MIT Press and Live Art Development Agency, 2011), p.324. ↩

- The book Out of Now contains the fullest collection of documentation on Hsieh’s works. ↩

- Groom, Time, p.12 [emphasis in original]. ↩

- Heathfield, Out of Now, p.324. ↩

- Thomas McEvilley, ‘Art in the Dark’ (1983), The Triumph of Anti-Art: Conceptual and Performance Art in the Formation of Postmodernism (New York: Documentext/McPherson & Company, 2005), pp. 233-53, p.249. ↩

- McEvilley, ‘Art in the Dark’, p.250. ↩

- Heathfield, Out of Now, p.327. ↩

- Heathfield, Out of Now, p.328. ↩

- Heathfield, Out of Now, p. 334. ↩

- Heathfield, Out of Now, p.334. ↩

- Heathfield, Out of Now, p.32. ↩

- McEvilley, ‘Art in the Dark’, p.250. ↩

- George Kubler, ‘The Shape of Time’ in Time: Documents of Contemporary Art, ed. by Amelia Groom (London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2013), p.29. ↩

- Heathfield, Out of Now, p.23. ↩

- Peggy Phelan, ‘Dwelling’ in Out of Now, p.345. ↩

- McEvilley, ‘Art in the Dark’, p. 238. ↩

- Heathfield, Out of Now, p. 324. ↩

- Heathfield, Out of Now, p. 326. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

So I accidentally came across Mr. Hsieh (through Marina Abramovic). Normally i am quite condescending about what people may call “modern art” or “minimal art” or “contemporary art”. But this is sure as hell no “art” in the way the feeble minded creatures call for example shit in a can.

This is a stance, a philosophy, a constant play. It is genius and the most original thing to see someone to REALLY express his philosophy and cosmotheory (meaning his perception about life), and to see that people all around the globe ensternize (meaning to adopt) a philosophical movement that has been in the depths of philosophy even from the old years.

To reach this kind of level, to say for example that life is a “sentence” you reach in the utmost level of understanding. This root philosophy can be traced back to Pythagoras / Plato and Aristotle and in their deepest teachings.

In any case, in the words of Nikos Kazantzakis, a Greek Writer (late 19th – mid 20th century), who was nominated for Nobel Prize for Literature, in his work Salvatores Dei (Saviours of the God) aka Ascetic, he says “Ερχόμαστε από μια σκοτεινή άβυσσο. Καταλήγουμε σε μια σκοτεινή άβυσσο. Το μεταξύ φωτεινό διάστημα το λέμε Ζωή”, which literally and exactly means “We originate from the dark abyss. Our finish is in the dark abyss. The inbetween time in light, we call Life”.

Very interesting commentary. Thank you.

You truly have to have a philosphical resolve to endure such a feat. It is obvious that TehChing has this resolve. His clarity in vision and intention is astonishing and truly beautiful.

My type of art.

The god of durational performance.

Huge respect for him. Always inspired to explore my mental capabilities the same way he explored his.

Not sure if someone else has had this experience, but I saw one of his pieces of art, and I just started to cry. I’m not sure if it is because my perception of his work was to not fear the absence of time, or if it was just the stillness of it, but it affected me deeply. Just throwing this out there.

I found his work very comforting. When and if you stop being afraid of death and accept it as natural and destined, you stop being worried of “wasting” time or not doing enough. You just live and pass time.

Mass depression time is a prison for many people this man documented the mental struggle of keeping going beautifully!

I’ve been in my bedroom for the past 6 years, i have never left my house or seen the sky. I can relate with this artist.

That’s a very very long time. No obligation to answer any of the questions I ask, but was it a choice you made or did you have no other option? What does your day look like? What do you feel/think after having been in your bedroom for such a long period; do you miss/want anything? I’ve stayed in my house for short term periods before without going outside, but the periods were often only a week or so long.

I don’t know i think it’s more of a mental depression i have going on (i think) my day is pretty bland, get up, wash/clean myself, eat, do stuff inside my room, sleep, repeat the next day. It started around 2016-17, have not been outside my house or talk to anyone besides my family members, and staying inside my bedroom ever since, I started to exercise and eat healthy makes me feel better now, and my mind is at ease sometimes.

Yes, there are times i wish i can go outside because i feel like I’ve missed out on so much things in the past 6 years which i know i will never get back (also i feel like my skills have gone in the past 6 years just staying home).

Maybe i will go out again when i feel fully comfortably, I don’t know if i have a mental illness, I have not asked anyone, i just keep it to myself.

Thank you for your answers 🙂 It’s really interesting to read about, and I’m sure you’ve probably also gained skills in this time! Maybe you don’t personally value them as skills when analysing your time, but someone else could find much value in them. I hope you feel better and that your mind stays calm. Do you have any friends that come and visit? I think it would be easier to go outside if you’re with someone you can trust and feel comfortable with; often if you’re walking with someone, you’re in your own bubble and what’s happening externally/around you is less noticeable. Or perhaps going outside at times when there are less people out- I used to do this. Like going to parks/fields very early in the morning, or going on hikes on weekdays when there is no one else around. Thanks again

Just a crazy artist which we love.

I’ve been telling friends about this artist for years and just stumbled upon your article. I was at the opening in 1980 in his TriBeCa loft in lower Manhattan. There were about 30 people there. We mingled around for 15 minutes. He came out, didn’t say a word, punched the clock and left. And that was it. I was blown away.

Thank you for sharing! That’s incredible.

Very glad I discovered this man when I did.

Passing the time with STYLE.

So much admiration for this man.

I think i get it. I’ve never allowed my inner city, no money having ass to see value in art thrown at a wall from a paint bucket. But this makes sense. Its one of those things that won’t make sense in the moment but when his life is over, you can see the beauty of it all in hindsight. Its kinda like life. For the greater majority of us, no matter how bad life gets, we always look back and see the beauty of it all.

I often scoff at “High” art and performance pieces, because most are pretentious and trying too hard to say something. However, on the contrary, Tehching Hsieh, he’s brilliant, he is not trying to say something, he literally BECOMES that something at will. To me that is the point of art, it’s not just expression or sending a message, but creating that thing you feel, envision or know and making it a real thing at will. He’s a genius in my opinion.

To each their own I guess. I don’t see high art here nor do I see something that should be praised or idolized. I see a man who was very likely mentally ill in some capacity very deliberately endangering and harming himself and taking pictures of it along the way. Am I supposed to be impressed? What a wasted, miserable life as far as I’m concerned.

This is great… I cant believe i just discovered this artist now.

This guy can be put in jail and not care.

Probably the only guy who can survive solitary.

This dude put himself in jail.

I have mad respect for people who decide to do mainly art in their life. People who go after their passion and have no existential doubts and fears. I wish I was that strong. I wish I was that alive.

Truly a powerful example of what can be done when you set your mind to it.

I just heard about him. This doesn’t seem like art. It seems like your one mentally ill friend with a drug problem that does a lot of stupid shit for attention and calls it art, like jumping out of a 2nd story window and breaking their ankles, like a jackass.

How did he afford to live during these performances?

In different ways. For example, he had a friend, or more like a “co-facilitator”, who was helping him out during Cage piece. There is more information on the day- to- day details in the book ‘Out of Now’ which I’ve cited, if you’re interested.

During one of his perfomances he lived on the street 100% of time, not going under any roof for one year. i think people like him have a different view on money and time. also I think he made enough cash to sustain himself til rest of his days by selling some of his works, I read some of his works were sold for 90+k $, now imagine how much is that for a guy who can literally live for nothing.

This was my curiosity as well… Maybe he saved up enough over the six years to do the one year project or maybe he got help from other artists in the scene.

Talk about suffering for your art…what absolute willpower he had.

Very cool stuff people might consider him insane but this a very interesting concept and i really like the work he does, sacrificing his own life for his work.

Imagine being able to live in New Your and not working for years! Where did he found enough money in a first place? Rent. food, clothing, other essentials?

His art to me sums up to existentialism. Being able to, capable of existing. Existentialism is in direct correlation with time. If you have time, you exist. If you have no time, you do not exist. You are able. He was able.

This is beautifully put.

When we look back on time, how does it change substantive experience? How does age change perception of time – when an experience of a year, profound as it could be – is in retrospection 1/10th of your life at age 10 but 1/50 at age 50.

Incredibly interesting article!! I love reading about art like this

King artist. A legend of the game.

I figured it was a critique of capitalism before i knew and it was right. Quite amazing i must say. Goes deep. Was never into performance art, but this guy does it right.

It’s a shame this man isn’t visible to the world. Never heard about him.

Life does feel like a life sentence. Highly relatable guy.

In a way, he expressed freedom by choosing to do something every day for a year. Living up to his own rules he set in place even though he didn’t have to, he chose to. And that’s why I think it’s a message of freedom and the passing of time.

He gave up on “life” but not on life.

A lot more meaningful & coherent than Damian Hirsch’s work.

This is actually wholesome modern art. I can support this.

So, this guy created “Lost”.

Might sound rather strange to say but it’s a shame he was born so early. With the power of TV, livestreams, YouTube, etc he could’ve exposed a lot more people to his art or done something totally different and more powerful

What a weirdo. I love him.

It’s interesting that his work contains normal human conditions of mostly everybody but pushed to the extreme. The time card, the actually being tethered to a single person, these are boiling what it means to work your whole life, and to be married to to literal expressions.

None of what he did even seems artistic. He just seems insane.

In this thought-provoking article, the author provides a detailed analysis of the artwork created by the renowned artist, Banksy. Through a critical lens, the author examines Banksy’s use of graffiti art to convey powerful social and political commentary on contemporary issues.

One aspect of the article that is particularly commendable is the author’s ability to provide a nuanced interpretation of Banksy’s work. By delving deeper into the themes and messages conveyed by the artist’s creations, the author sheds light on the complexities of Banksy’s artistic vision. Additionally, the author’s thorough research on Banksy’s life and career offers readers valuable insights into the artist’s background and influences.

However, one potential criticism of the article is that it may be too technical and jargon-heavy for some readers. While the author’s use of art terminology and critical theory is impressive, it may be difficult for those without a background in art to fully grasp the author’s arguments. Moreover, the article could benefit from more images of Banksy’s artwork to help illustrate the points being made.

Overall, this article is a must-read for anyone interested in Banksy’s work or the intersection of art and politics. The author’s keen eye and deep understanding of art provide a captivating exploration of one of the most influential artists of our time.

I think you got the wrong article. This one is about Tehching Hsieh, not Banksy.

I appreciate the historical context given here. I’ve heard of this fellow before and found him interesting, but it isn’t until now that I can more or less understand him (as much as one can with this guy)