The Persistent Allure of Victorian Literature

The Victorian period, named for England’s Queen Victoria, ran for 63 years, from 1837-1901. It encompassed several major historical events around the world, from the Crimean War to Manifest Destiny and Westward Expansion, from the Industrial Revolution to the Civil War and Reconstruction. Yet, if you say “Victorian,” a lot of people will think of the United Kingdom. They may also think of popular tropes associated with Victorian fiction. Well they might, because this sub-genre is one of the biggest in literature. Several books and authors now regarded as “classic” come from the Victorian era. Some books are so beloved, they’ve received adaptations across other mediums like film and theater.

Why does Victorian literature stick with us more than other sub-genres? Why do we associate it with so many beloved characters and tropes? The answer is multifaceted, encompassing several elements. In a nutshell though, perhaps Victorian literature allures readers so because it contains something for everyone.

Evergreen Plots

“Evergreen,” used in terms of content, is a Search Engine Optimization (SEO) term meaning, “content…[continually] relevant for readers.” For the purpose of our discussion, the conflict in literature is “evergreen” if readers from past and current time periods, and all social groups, find it relatable. A close look reveals most if not all central conflicts in Victorian literature fit the bill.

Oliver Twist

Let’s begin with Charles Dickens, one of the most prolific and well-known writers of the Victorian era. Dickens created characters and worlds that gave readers unvarnished looks at the harsh realities of Victorian London. Oliver Twist takes readers from the workhouse, the last “refuge” of London’s most desperate, to the underworld of the streets, giving humanity to everyone from the innocent orphan to the hardened criminal. Oliver Twist juxtaposes benefactors with people who claim that distinction, yet treat those they are meant to help as burdens at best and chattel at worst. Mr. Brownlow and the Maylies are the former; they are foils to minor yet memorable antagonists such as parish beadle Mr. Bumble and the avaricious street lord Mr. Sikes.

At first, Dickens’ explorations of poverty might seem relevant only to their era. Developed nations don’t use workhouses anymore. The closest equivalents, such as homeless shelters, endeavor to make residents feel welcome and provide them with meaningful work. And while some kids and teens roam the streets like Dodger and Oliver, this isn’t considered a good solution for their situations. In fact, the stated mission of most social and charitable services involves shielding kids from modern street dangers.

However, the average 2020 reader often finds Oliver Twist resonates with him or her. Many of us have lived through the 2008 recession. Unless we were young children, we remember how it affected us. Modern resources mean that hopefully, most readers weren’t in imminent danger of being separated from families or thrust into abusive situations. Still, many people experienced great anxiety and hardship after losing jobs or businesses. Homelessness and food insecurity became more immediate issues, especially for children. Elderly persons, persons with disabilities, and people from other marginalized groups struggled harder than usual to carve out their places in the world. This writer, a permanently disabled person who was then a recent college graduate, was almost completely housebound for over two years, despite continuous efforts toward gainful employment. She became terrified of being placed in a group or nursing home if her parents’ financial situation became untenable.

Unfortunately, such troubles didn’t end for this writer or others when the recession did. In 2016, the U.S. elected Donald Trump, possibly their most controversial president ever. In the following three years, many Americans blamed Trump for their continued hardship, especially as related to healthcare access and employment opportunities. In March 2020, the coronavirus that turned life upside down for the people of Wuhan, China found its way to the U.S., the U.K., and across the world. Deaths from the so-named COVID-19 virus shook families on a similar, yet much grander scale than orphan-hood and other losses shook Oliver, the Dodger, and others. Businesses shuttered, at first temporarily but now perhaps for good. Schools went from safe havens for children, to confusing places where remote learning, face-to-face instruction, or varied combinations failed to meet basic needs.

Especially within 2020 and the preceding decade, readers can see smaller parallels to Dickens and Oliver. For instance, the pandemic has made life particularly difficult for children like Oliver. They may be unable to leave abusive situations or may have lost common refuges such as extracurricular activities. Increasing incidence of depression and suicidal ideation, as well as the aforementioned poverty, mean that some teens and preteens turn to street or gang activity for a sense of purpose. Those aging out of foster care are no longer guaranteed a physical college, job, or military base at which to start building independent lives. They are instead offered virtual, hybrid, or work-from-home options. While well meant, these options may isolate them further from peers and common life experiences.

Dickens readers of all ages have often found themselves unsure who to trust or how to navigate new and overwhelming situations. While pandemics, contentious elections, and rioting don’t help, it doesn’t take those situations for readers to go identify with down-on-their-luck characters. A devout believer may turn away from faith. A business associate who promises help and friendship may turn out to be a Fagin or Sikes, backstabbing innocent people for their own gain. Women may want to embrace feminism, but find some representations harmful and confusing. Thus, they may feel as beleaguered as Nancy and Bet sometimes feel. Minorities like Fagin, who is explicitly called a Jew in Oliver Twist, seek ways to rise above the way the majority has stereotyped, maligned, or subjugated them. At times, as with Fagin, this leads to questionable if understandable lifestyle choices. And while many of our cities are cleaner, better organized, and “friendlier” than the streets of Victorian London, some are not. This is especially true if you are in any kind of minority position.

These days, Oliver Twist is not read as widely as it once was. Contemporary audiences often shy away from it because it’s a “classic” and allegedly hard to understand, or because the protagonist is a young child. However, Oliver Twist‘s themes, and the main characters’ reality, are not at all childlike. Actually, this novel remains evergreen, whether someone reads it in a homeless shelter, on a corner while waiting for transit, or in the comfort of a reading nook.

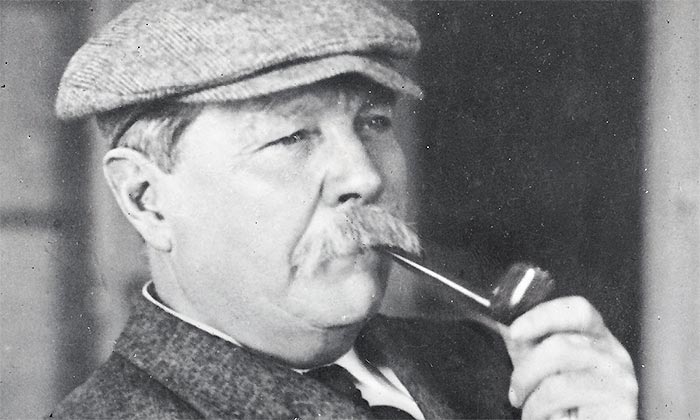

Sherlock Holmes Stories and Novels

Charles Dickens wasn’t the only Victorian author to provide evergreen plot lines. Some of the genres of Victorian literature can be considered evergreen. Perhaps the best example is Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and his Sherlock Holmes stories, as well as the Holmes novel The Hound of the Baskervilles. Mysteries had intrigued readers before the Victorian period and have done so ever since. During Doyle’s years of writing, true crime stories like that of Jack the Ripper enthralled, frightened, and baffled readers. The chilling possibility of dangerous criminals roaming free keeps mystery pages turning. So too does the reader placing him or herself in the shoes of the star detective. Most readers, Victorian, current, and everywhere in between, like to “play along” when enjoying a mystery. Sherlock Holmes is perhaps the most popular and fun detective to “play along” with.

Holmes, Watson, and their compatriots maintain the conventions and aesthetics of Victorian literature–foggy London streets, cloaked figures in dark alleys, secrets and scandals. In “A Scandal in Bohemia,” for instance, Holmes comes to the aid of a German count hoping to conceal his affair with American actress Irene Adler. The problem is, she possesses a compromising photograph, which she uses as blackmail. Whether or not they agree with the count and Irene’s actions, readers can identify with the stakes of the story. They can relate to the complications of love, lust, and everything in between. Most of them have probably encountered similar scandals everywhere from reality TV to the nightly news, and have sided with one party or the other.

Additionally, readers can enjoy how timeless Holmes’ deductive reasoning is in this story. After fruitless efforts to make Irene Adler confess or give him the photograph, Holmes decides to make her “show” him where she keeps it. Once he has the photograph, Holmes might succeed in convincing Adler to drop her blackmailing scheme. After impersonating an injured reverend, Holmes is taken into Miss Adler’s home to “recover.” He then signals Watson to toss what amounts to a homemade smoke bomb through an open window. Thinking her home is on fire, Miss Adler rushes to save the photograph. Later, Holmes tells Watson how he could be so sure Miss Adler would reveal the photograph’s location. When her house is on fire, he says, a woman’s natural instinct is to protect what she most values. “A married woman grabs for her baby, an unmarried woman [her] jewel box,” he expounds. It’s a simple bit of deductive reasoning when stated, and Holmes’ examples may not hold up as well in 2020 as they did when “A Scandal in Bohemia” was published. But unlike the ordinary reader, Sherlock Holmes used deductive reasoning to solve a mystery and a time-sensitive problem. Plus, he did so as part of a multi-step, flawlessly executed plan. No matter what century they’re in, readers can appreciate and cheer for a protagonist whose brilliance always serves him well.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle pulls off another famous evergreen Holmes plot in Hound of the Baskervilles, his only Sherlock Holmes novel. As with Dickens’ novels, the plot of Baskervilles doesn’t look evergreen. The surrounding mystery is blamed on the attack of a giant supernatural hound stalking the English moors. Many of today’s readers claim religious faith or a connection to the supernatural, which could include ghostly beings similar to the hound. Yet, since Baskervilles’ publication, the use of a supernatural whodunit is less common in mystery stories. Additionally, the motive for the mystery is archaic. That is, the criminal wants to take hero Sir Henry’s inheritance for him or herself, out of jealousy toward the noble Baskerville family. Since America no longer acknowledges a class system and the United Kingdom’s systems have modernized, such a motive comes across as “removed” from why today’s criminals engage in their behavior.

That said, love and money are timeless motives in the real world and in books. So while today’s readers might not identify with the expectations of nobility, they can understand why a huge income and a large, well-known house would be major temptations. And while most readers don’t fear supernatural hounds, every reader is afraid of something. Thus, they will root for Sherlock Holmes and Watson to uncover the “hound’s” true origins. When that happens, Sir Henry can have what is rightfully his, and so a killer, human or animal, will not strike again. In the meantime, readers can enjoy speculating on who and what the hound is, whether a human can be held responsible for its attacks, and how Holmes will piece together various clues. Common mystery conventions like red herrings, or false leads add to the intrigue. The fact that Baskervilles is a novel rather than short story also gives readers more time to delve into other conventions of plot and character.

Relatable, Clear-Cut Characters and Positive Character Journeys

No memorable story can exist without strong characters. Some of the strongest and best known are in Victorian literature. While they are relatable to readers of this century, Victorian characters carry a charm unique to their fictional worlds. That is, in Victorian literature, it can be easy to discern who is a hero and who is a villain. This gives readers a sense of comfort and security, but it doesn’t mean the characters are shallow. To the contrary, some of these clear-cut Victorian characters are some of the most complex and beloved in the Western canon.

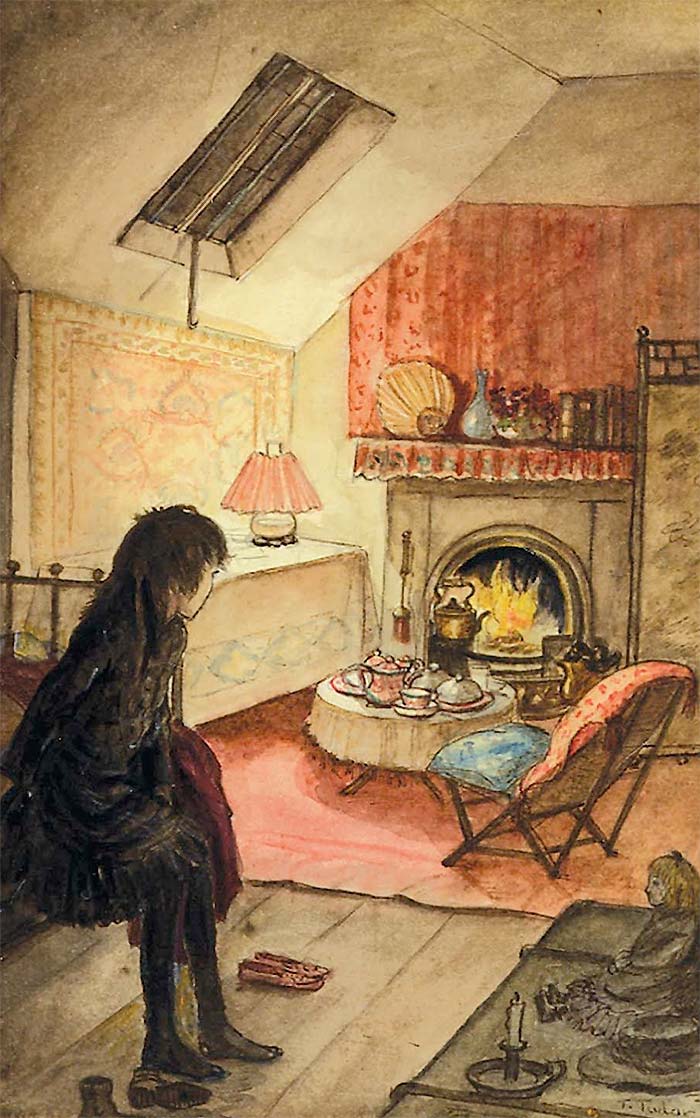

A Little Princess

Some of the best examples come from Frances Hogsdon Burnett’s A Little Princess. Although first published as a novel in 1905, A Little Princess was serialized in popular magazines throughout the later years of the Victorian period. It’s also regarded as a fairytale novel, with several fairytale conventions, including how its characters interact. A Little Princess introduces us to Sara Crewe, a seven-year-old, privileged English girl who has grown up in India but returns to England to attend boarding school. During the book, Sara ages into her mid-teens, although her exact age is unclear (the book does not tell us, and most adaptations place Sara between ten and twelve). Whatever her age and however long she is at boarding school though, Sara faces the same adversary, unyielding headmistress Miss Minchin.

From the outset, readers are meant to know Sara is an almost perfect protagonist. She’s given flaws, but some are specific to the Victorian period. For example, while classically pretty Victorian girls have blonde hair and blue eyes, Sara has dark, almost jet hair and green-gray eyes often called “odd.” Sara is more serious and thoughtful than most “normal” children her age, not given to exuberance or emotion as an “ideal” child would be. Flaws that could affect her character, such as temper, are ones Sara keeps under tight control.

When describing Sara, Burnett admits she’s spoiled thanks to a lovingly indulgent, widower father. Sara owns more and better toys than most children could ever dream of. Her clothing is exquisite, and Burnett treats readers to flowery descriptions of some items. Sara enters Miss Minchin’s Seminary for Girls with a French maid paid to attend her every whim, a horse and carriage, and authentic Indian artifacts, such as a life-size stuffed tiger. Yet while most children with such privileges would act bratty at least occasionally, Sara never does. Burnett makes clear Sara’s richness of heart outpaces her material wealth. She pays special attention to outcast students like Ermengarde St. John, mothers little Lottie Leigh despite her constant tantrums, and “scatters largess” to poor people in public. In other words, Sara Crewe lives and behaves as a princess in all but title. Possessed of a vivid imagination, Sara sometimes pretends she’s a princess, but readers sense she hardly needs to. She already embodies everything important about the character type.

For every princess, there is a wicked adversary. Miss Maria Minchin, headmistress of the Seminary for Girls, fits the bill. She covers it up at first, acting the part of the proper teacher. The act seems to work on Captain Crewe, but his daughter notices Miss Minchin is a little too sweet. The longer Sara is at the Seminary, the more she and Minchin clash. Most confrontations are understated, and Minchin is actually not present for some of them. Yet Minchin and her status quo are always felt, emotionally if not physically. When Sara befriends Ermengarde St. John, for instance, it sends a message that the chubby girl who has terrible trouble academically is no longer an outcast. This threatens both student social circles and Minchin’s status quo. An outcast student is a perfect target for a gaslighting teacher who uses a disapproving parent–Ermengarde’s strict academician father–as a threat. A student who receives patient tutoring and friendship from a popular peer is no longer an easy target. Thus, Minchin has to focus on the “bigger fish” in the picture–Sara. She also has to drop her facade.

Victorian novels tend to rely on coincidence. A perfect one is dropped in Miss Minchin’s lap about halfway through A Little Princess. Sara’s father dies, leaving enormous debt and an unfulfilled promise of connection to diamond mines. Unable to recoup her losses, Minchin makes Sara a “maid of all work” alongside the abused Becky. She sells all Sara’s luxurious possessions, forces her to teach younger students without pay, and will probably indenture her for years if not decades to come. Clad in a too-tight, too-short black dress, Sara begins grueling work almost the moment she learns of her father’s death. The other servants are only too happy to belittle the former “princess” and hand her the hardest tasks they can, from scrubbing floors and peeling potatoes to carrying full coal scuttles between floors multiple times a day. Sara notes she is treated marginally better than Becky. That said, Sara soon becomes another victim of overwork, starvation, periodic physical abuse, and other indignities.

Half the fun of stories like A Little Princess is rooting for “the good guys” to get a happy ending. It’s also fun to root against the villain, and commiserate with the protagonist. Sara Crewe lets readers do both, as her hardships and triumphs give more nuance to the classic “Cinderella” formula. Sara doesn’t have sentient mice to talk to, but she does have Becky, who becomes her sister in travail. The two often imagine themselves in the Bastille and use secret codes to communicate. Eventually, Sara brings Ermengarde and Lottie in on the “mysteries” of her new life; film and miniseries adaptations show her maintaining friendships with other girls, too. Especially in adaptations, Miss Minchin and her allies constantly remind Sara she’s no longer a princess. But the more they say so, the more determined Sara becomes to prove them wrong. She may no longer have the wealth and privilege of a princess, but she can act the part better than ever before. Readers stick with her to see if she can maintain her attitude, and if it will pay off.

Burnett doesn’t disappoint. Again, the conventions of the Victorian novel mean Sara’s happy ending is guaranteed. The catch is, those same conventions mean the journey to said ending will be plenty tough on our heroine. Every time Sara’s “princess” attitude starts to feel too perfect, Burnett reminds us of her reality. Sara is not just a maid of all work; she’s worked off her feet, which would be hard on anyone but doubly so for a girl who’s not even a teen yet. She’s no longer a student tutor; she’s expected to teach all the younger pupils, presumably with the hours and expectations placed on an adult instructor. Her clothing is never replaced, meaning it is as worn and ragged as Becky’s. Over time, the few privileges Sara gets, such as a bit more food, fade into the background. By the time we hit the climax, she’s starving. “I’m so hungry, I could eat you,” Sara snaps when Ermengarde naively asks if hunger is a problem for her. At one point, Sara is so distraught, she throws her formerly treasured doll Emily across the room. “You can’t feel…you’re nothing but a doll,” she cries. It’s a gut-wrenching moment in a series of sobering ones. Sara can handle hunger–in fact, she can do so well enough to give up the majority of mini sweet buns she’s able to buy to a beggar girl. She can handle Minchin’s verbal and other abuse because she’s seen through her enemy from the outset. What she can no longer handle, and what she takes out on others, is the loneliness and isolation of her new position. When Minchin takes full advantage of this and punishes Sara’s friends for maintaining contact, she drives home the message Sara fears: “You’re not a princess. You’re no one at all. No one cares about you and you don’t deserve their regard.”

Perhaps it’s moments like these, and Minchin’s one-dimensional evil, that make Sara’s ending satisfying. Readers find out the school’s next door neighbor is Mr. Carrisford, the same wealthy man who’s been searching for Sara since Captain Crewe died. The Indian gentleman who provides “magic” such as food and warmth for Sara and Becky, is Carrisford’s servant. The Large Family Sara has watched and envied for months are Carrisford’s friends, and Sara’s chance encounter with one of their sons is the impetus for Carrisford finally locating her. As quickly as she became a drudge, Sara is restored to wealth, more than she ever possessed. Carrisford adopts her almost on the spot, and defends her when Miss Minchin tries to claim that legally, Sara must return to the school and pay off her father’s debts. The last we see of Sara, she is making a substantial donation to the bakery whose owner sold her sweet buns. Sara also reconnects with the beggar girl, whom she learned was taken on as the baker’s apprentice. The whole situation is built on one coincidence after another–and readers love it. Several modern adaptations reveal they still love it today.

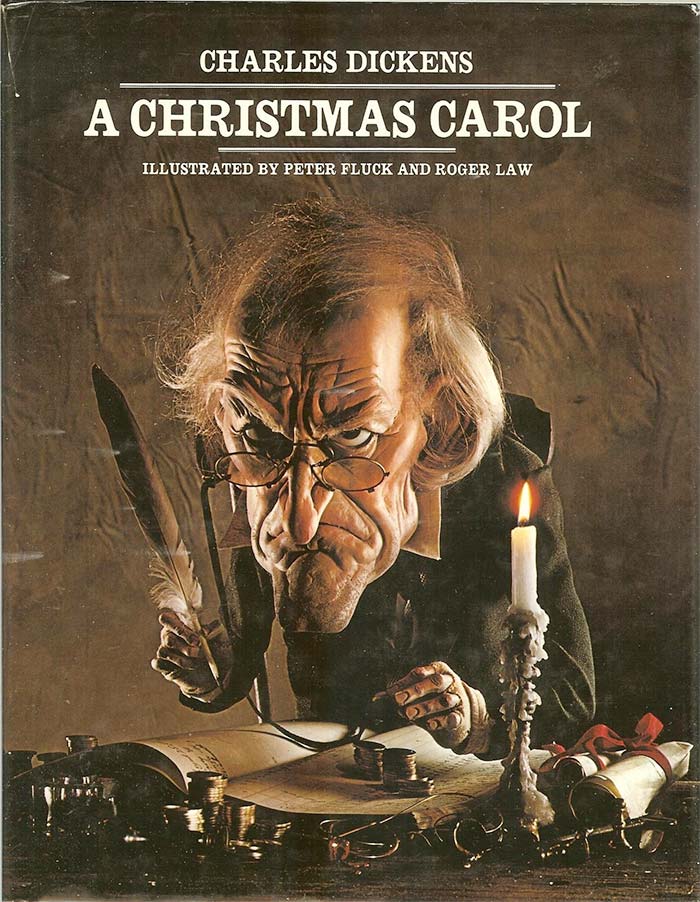

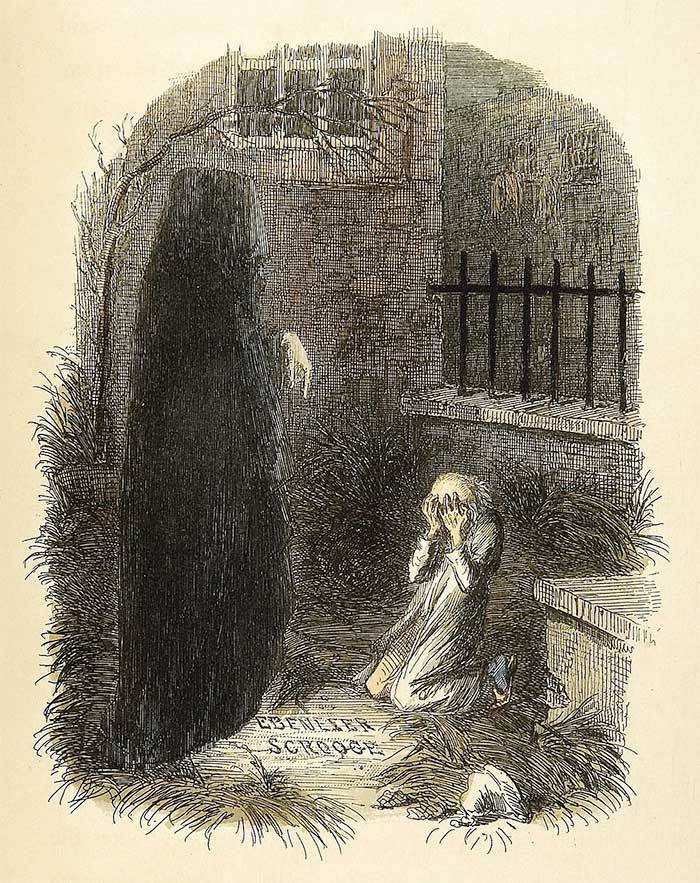

A Christmas Carol

A Victorian novel need not be a fairy tale to give us clear-cut, yet lovable characters. Easily recognizable “good guys” and “bad guys” can be found in other genres too, like the ghost story. Perhaps the best example comes from our old friend Charles Dickens, whose A Christmas Carol has been hailed as a masterpiece practically since its first publication in 1843. Since then, the novel has sold more than two million copies and has never been out of print. It’s been adapted into stage plays, Broadway musicals, three live-action films, one Muppet movie, one Mickey Mouse cartoon special, and modernized novels or TV films like Ebenita, starring Cicely Tyson.

A Christmas Carol is the definition of a morality tale. Ebeneezer Scrooge defines “unlikable lead.” He’s such a cold, ruthless man, his name is now synonymous with heartlessness. He’s had chances at a happy life with a woman he loved, possibly children, and caring friends, yet threw it all away for financial gain. By the time we meet Scrooge, he’s an old, bitter soul who browbeats his employees, especially clerk Bob Cratchit. Scrooge’s only living relative, nephew Fred Holywell, is portrayed as a saint for putting up with his uncle. Scrooge lives alone, affords himself minimum creature comforts, and doesn’t think anyone else deserves “comfort and joy” either. He calls the impoverished people of London “the surplus population,” implying said people are better off dead.

A Christmas Carol’s simplicity doesn’t stop at its one-note “protagonist.” Its other characters are easily categorized as well. The aforementioned Bob Cratchit is Scrooge’s antithesis, a poor man, but a steadfast provider and a loving father. His disabled son Tiny Tim is an angel in human form, frail but brave, forever forgiving and often spouting nuggets of wisdom.The threat of this character’s death is arguably the one thing that gets Scrooge to change, not just so he can avoid his own death (and an implied hellish eternity), but so he can do some good for his fellow humans. As for other secondary characters like the Cratchit family, Old Fezziwig, and Scrooge’s sister Fan, they’re pretty one-note, too. Most of them serve only as Scrooge’s mirror, showing him how awful he’s become in comparison. To modern readers, some portrayals are saccharine; a lot of disabled readers shun Tiny Tim, for instance, because he’s a stereotype and because he runs the risk of dying for the sake of Scrooge’s character development. Simple and saccharine or not though, readers return to these characters every holiday season, not because they want Scrooge and “friends” to go on a deeper journey. The presence of so many good-hearted people communicate faith, hope, and love exist in the world. When juxtaposed with Scrooge, a personification of evil, the Christmas cheer that could become overwhelming becomes refreshing.

The charm and allure of A Christmas Carol doesn’t end there. As a ghost story, its greatest value hinges on the three, technically four, spirits haunting Scrooge. They too are simplistic; they’re the supernatural beings sent to do what people cannot do for a lead who refuses to change. They might as well have “Symbols of Redemption” tattooed on their foreheads. Jacob Marley not only arrives draped in chains and metal bank boxes, but explains the symbol so Scrooge knows exactly what sins he is committing. Later, the Ghost of Christmas Past tells Scrooge to be careful in upsetting her, lest he ruin his chance of reclamation (most adaptations either portray this ghost as a female or an animated entity voiced by a woman).

The ghosts speak in extremely concrete terms or images. In the 1984 George C. Scott adaptation, the Ghost of Christmas Present pulls no punches about Scrooge’s attitude toward the destitute. “[You are] more worthless and less fit to live than millions like this poor man’s child,” he exclaims during the visit with the Cratchit family. Christmas Past isn’t shy about telling Scrooge he lost his true love to “a golden [idol].” Christmas Future’s message is so clear, it ends with the spirit’s gaunt finger jabbing toward Scrooge’s headstone.

However, the Ghosts of Past, Present, and Future lend more depth and gravitas than a typical ghost story. They show Scrooge myriad scenes of the truth that his choices could ruin him, and the truth that there’s still time to make things right. Every scene gives Scrooge a new angle on why and how he’s chosen his current path and what he should do in response. From Past, he learns it’s too late to go back, but not too late to resurrect the hopeful person he once was. Present shows Scrooge not only do the people around him care for him, but he is able to show love and empathy back to them, if he lets his guard down. As for Future, its message has a lot more than, “Change or die.” The more enduring message of Future for Scrooge and readers is, “The future is nearer and more relevant than anyone believes. It’s made up of what we do in life. Wise, compassionate decisions will ensure our lives stack up to the past, present, and future we want.” The ghosts of Dickens’ story remind us the end is inevitable; Scrooge will die someday, as everyone will. Fortunately for Scrooge, he recognizes it’s never too late to change.

Do readers love A Little Princess, A Christmas Carol, and similar Victorian stories because they’re “easy?” Do they prefer completely good or completely evil characters to complex ones? Both novels suggest the answer is actually “no.” It’s true, Sara’s perfection and coincidental “rescue” wouldn’t work for most of today’s publishers. Scrooge is a flat character, arguably too mean to be believed, and arguably too quick to change. Some of Burnett’s overblown descriptions are annoying. Dickens gives readers a straightforward morality tale rather than a multifaceted portrait of human nature. Neither plot would hold up well today, so why do readers hail the novels as classics?

Readers let these shortcomings slide because inside the problematic “package” is the timeless struggle of good and evil. Further, the “package” means it’s not enough that good wins. Readers want to see “good”–Sara–get everything she deserves and lost through no fault of her own. They want to see characters like the Cratchits get a shot at happiness and security. They want to see “evil”–Minchin–not just defeated, but crushed and never heard from again. They want to see Scrooge fully understand the consequences of his actions and make a permanent change. Burnett and Dickens fulfill all requirements, showing us the purest forms of good can still triumph in a dark and complicated world. Such triumph, and the accompanying defeat of evil, might usually be more subtle than in a Victorian novel. Sometimes though, the struggle will be a bit more epic. In cases where it’s not, modern readers can still have the satisfaction of knowing they were on the right side and did the right things.

Heavy But Hopeful Themes

Contrived coincidences and clear-cut characters aside, Victorian literature isn’t for the faint of heart. Dark and heavy Victorian novels attract readers too. The period’s darker offerings plumb the depths of human nature, inviting readers to engage in the struggle of good and evil with more nuanced plots and characters. They invite us to explore dangerous situations from the safety of our reading rooms. They scare us, showing us what could happen to us and others if we allowed our darker instincts to rule. Yet, these themes are tempered with hope or love so the darkness never feels overwhelming.

Jane Eyre

A wonderful example is Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, published around 1847. The titular protagonist is placed in classic Victorian hardship; she’s an orphan, and her only relatives are constant and unrepentant in their cruelty. Jane’s maternal aunt, Mrs. Reed, verbally and psychologically abuses her. Jane’s cousins, especially the oldest, John, are also abusive. In the novel’s first scene, John twists Jane’s arm and throws a book at her head, which knocks her off balance. Jane hits her head in the ensuing fall, drawing blood. But when she fights back, she’s labeled the aggressor and locked in “the red room” as punishment.

Said punishment seems innocuous if excessive. However, Jane’s experience is no gentle, temporary isolation. She begs Mrs. Reed not to lock her in the red room. “I cannot endure it,” she cries, suggesting this has happened several times before, and Jane’s emotional torment is the primary reason for the red room’s use. Of course Jane, as the “always browbeaten…forever condemned” protagonist, has no choice. She must endure the red room, a place Book Riot writer Maddie Rodriguez calls “Gothic [and] lurid” in the extreme. Shades of red from crimson to vermilion dominate everything from the bedclothes to the wallpaper, a visual assault with no relief. Anything not red, such as wooden furniture, is dark to the point of blackness. Film and other adaptations show the red room with cherry or other dark wood furniture. The room is a spare chamber and thus, isolated from activity. It’s completely silent and devoid of distraction, meaning Jane has plenty of time to let her “imagination and feelings” run wild.

Run wild they do, straight to the supernatural. The colors and shadows of the red room make Jane hallucinate a ghost, whom she imagines is her late Uncle Reed. At first, she hopes if Uncle Reed could return from the dead, he would defend her. But this hope dies fast, and Jane is left convinced her uncle, or any other visiting spirit, would take out supernatural rage on her instead. She becomes almost catatonic with fear, and when she’s finally released, nursemaid Bessie finds Jane has made herself physically ill. Jane is consigned to the nursery to receive medical treatment. Mere days later, Aunt Reed ships her off to Lowood School as a “charity pupil,” warning headmaster Mr. Brocklehurst of her niece’s alleged delinquency. Since Brocklehurst abhors “sinners,” and since most of the other teachers follow his authoritarian lead, Jane is further victimized. Her heart and soul remain locked in a mental and emotional “red room,” where she is bombarded with her sins, failings, and general low position in Victorian society.

To Jane’s credit, she doesn’t let her personal “red room” break her spirit. Thanks to allies like her friend Helen and sympathetic teacher Miss Temple, Jane allows her faith in God to grow. This shapes her into a meek and patient yet strong heroine who personifies the phrase “grace under fire.” Additionally, Jane takes refuge in academics, accepting a governess position at Thornfield Hall. Some aspects of Thornfield, like mysterious, guttural laughter, put her off at first. But Jane is used to physically and emotionally cold environments. She’s used to being shut out or told it’s not her place to know or do certain things. In her usual understated way, she determines to make Thornfield Hall as much a home as possible. She throws herself into becoming the best governess possible for Adele Fairfax, who is much more exuberant than Jane was as a girl but, like her at that age, is without guidance or love.

Jane’s life takes an unexpected turn for the better the longer she’s at Thornfield. Eventually, she meets Edward Rochester, the master of the house. Their first encounter is a bit unconventional. Rochester nearly runs Jane down on horseback while she’s out walking. Not knowing who Rochester is, Jane reprimands him, and then fears she’ll lose her job, her independence, and her sense of security when Rochester reveals his identity. Instead, Rochester finds Jane intriguing. Her intelligence, compassion, and patience with Adele inspire Edward to seek a relationship, and they quickly become close. Jane breaks through Edward’s cold exterior, while Edward becomes the first and only man to treat Jane with respect and dignity. More importantly, Rochester is one of only a handful of people to show Jane real love–at first platonic and gradually romantic. For a while, it seems Jane will find permanent happiness at Thornfield and banish her inner “red room” and accompanying demons for good.

As inner demons will though, Jane’s aren’t going to let her off that easily. The “ghost” of Thornfield tries to sabotage Jane and Edward’s relationship several times, going so far as to murder a house guest. However, the darker Thornfield’s environment gets, the more Edward and his staff deny anything untoward is happening. No one consciously gaslights Jane, least of all Edward, but Jane feels the effects anyway. She buries her emotions long enough to accept Edward’s proposal, but her heart shatters when she discovers Edward is already married. Edward has refused to annul his marriage or institutionalize Bertha Mason, choosing instead to shelter her for years. In return, Bertha has caused all manner of chaos. When Jane discovers the depth of Edward’s subterfuge, and that he defends Bertha, she runs from Thornfield and her chance at love. In Jane’s mind, someone meant to care for her has once again put their selfish desires first and made Jane feel she must pay for their choices and behavior. The storms that constantly rage through this part of the novel echo the instability in Jane’s heart.

Bertha Mason is a bit like Jane’s other adversaries. Like Mrs. Reed and Brocklehurst before her, Bertha doesn’t understand Jane and thus, unleashes malevolence on her. Yet unlike Reed or Brocklehurst, Bertha doesn’t know the extent or consequences of what she’s doing. Like Jane, she’s been traumatized and scarred, but Bertha’s scars are so deep, she can’t function outside them. Bertha no longer recognizes there is a world around her, a world of people and places who could love her or give her the shelter, solace, and safety she needs. Rather than seeking those, Bertha turns to destruction, such as when she sets fire to Edward’s room or commits manslaughter. In many ways, Bertha becomes Jane’s “shadow twin,” or the woman Jane would be if she too allowed the darkness of her life so far to take over. Jane runs from Thornfield and Edward then, not so much because Edward committed polygamy, but because she fears staying will draw her too close to Bertha. Dealing with Bertha in any way means Jane has to accept Bertha’s fate could be hers.

Charlotte Bronte does not neglect the hopeful underpinnings that provide relief from Jane Eyre‘s heavy themes. When it seems Jane will follow Bertha’s mental and spiritual trajectory, she meets up with the Rivers family, cousins on her father’s side. They give her much-needed physical healing and comfort, and do their best to salve Jane’s post-traumatic stress. Jane’s cousin St. John proposes and suggests she join him in the mission field, making a clean break with her past. Jane considers it, but distance from Thornfield and Edward have given her valuable time for introspection. Thanks to the Rivers clan and the long-ago encouragement of allies like Miss Temple, Jane’s inner strength finally reaches a pinnacle. In finding kind biological relatives, Jane finds the family she never had and anchors herself with much-needed stability. However, in rejecting St. John–thus, rejecting the easy way out–Jane learns she can do more than run from her problems. She doesn’t have to leave every time the darkness creeps up on her; she doesn’t have to compromise herself to avoid pain; she can deal with her emotions without treading Bertha’s path. As Jane later says, she is no bird and no net ensnares her. She learns to “fly” when she can fully accept every part of herself and her nature, the dark as well as the light.

Secure in who she is as an independent woman, Jane returns to Thornfield, her love for Edward rekindled. When she finds him blind, burned, missing a limb, and grieving over Bertha’s suicide, Jane embraces him literally and figuratively. She vows to stay by Edward’s side as a wife, caretaker, and friend. Unlike other times though, the vow doesn’t come because Jane is without a choice. Jane chooses Edward, Thornfield, and any associated hardships because she has seen the darker side of humanity. She has walked through it, and made the difficult choice to let light, love, forgiveness, and virtue rule in her life. Jane faced her red room, fought for hope, and won. Her traumas may come back to haunt her–modern psychology tells us scars like Jane’s never completely go away. Jane’s “ever after” may not always be perfectly happy. Still, she will be healed and hopeful ever after.

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

Also known as Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, this Victorian novella might seem odd for our discussion. First published in 1886, it fits the Victorian time frame, and its author, Robert Louis Stevenson, was originally from Edinburgh, which places him with the rest of our authors in the United Kingdom. Additionally, the story of Jekyll and Hyde carries the same dark themes Victorian readers often expect from this period’s writings. But it seemingly lacks the hope element.

However, Jekyll and Hyde belongs in our discussion as much as any other work we’ve covered, for its darkness as well as its hope. With a title like The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, the potential macabre nature punches the reader in the face. From the cover onward, Stevenson delves into the worst of human nature. One of Jekyll and Hyde’s opening scenes shows Edward Hyde assaulting a young flower girl in broad daylight. The ensuing discussions of Hyde’s character add to the novella’s mysterious nature. Readers get hooked on the story as they wonder, who exactly is Edward Hyde? What motivates him to commit evil acts, other than for the sheer pleasure of such (if indeed he has a deeper motive, which some Victorian characters don’t)? Most of all, why would anyone leave everything to such a reprehensible person in his will?

In answer to the last question, coercion and blackmail might top readers’ motive lists. Had Stevenson gone that route, Jekyll and Hyde would’ve maintained its dark, heavy nature. To his credit, Stevenson pushed the 1886 envelope instead. He gave readers something they’d never seen before–a protagonist literally trying to split himself in two. Victorian and modern readers are invited into Dr. Jekyll’s laboratory and treated to all the spine-chilling scientific accoutrements and evidence of experiments their hearts desire. Readers are also challenged to think about what might happen if a person could separate out parts of themselves. The prospect is tempting if not scientifically or technologically possible. Dr. Jekyll wins sympathy and empathy, because all readers have something about themselves they’d like to get rid of.

Underneath the readers’ empathy, darkness continues pulsing. Readers see Jekyll is at once terrified of and fascinated with his baser human instincts. Perhaps that’s why alter ego Edward Hyde is such a caricature. Hyde is not a “normal” person whose personality leans toward unpleasant moments. He is not merely the type to browbeat a bartender or knock over a beggar in the street. Hyde is Jekyll giving full vent to every dark impulse he’s ever possessed, up to and including cold-blooded murder. Jekyll’s choice to make Hyde wholly evil invites readers to probe why this is. How frustrated or repressed does Jekyll feel, and how long has he suffered? As they probe this question, readers are again challenged–not just to say “what if,” but to face the Hydes within.

Most of us would never murder someone, but we have, and will, say and do things we regret when “Hyde” is on the loose. Depending on how we interpret our behavior, we might find we are more like Hyde than we ever wished to be. A devout Christian who lashes out in anger might feel particularly convicted because Jesus said to react in anger was to murder your “victim” in your heart. A Buddhist or Hindu might suffer intense guilt for killing a bug or other hapless creature due to teachings on reincarnation. Even someone who claims no religious faith will probably react with “sober judgment” to the cautionary tale that is Hyde (Romans 3).

Unfortunately, Jekyll himself doesn’t heed the cautionary tale he’s created. He tries to control Hyde and repair the damage he causes. At least once, Jekyll resolves to be done with Hyde altogether, refusing to take the self-altering potion that transforms him. But by then, Jekyll has exposed himself to his dark side so often, he changes without full use of free will. As noted, he commits murder at the pinnacle of his desperation. And just as rage swallowed Jekyll in Hyde form, guilt and remorse pull him under once he realizes the consequences of his actions. In a classic example of the anger turned inward that causes clinical depression, Jekyll retreats into himself for the last time. But instead of locking the laboratory door and altering his physical appearance, Jekyll commits suicide. He eliminates both sides of himself from the equation of humanity. Because neither side will satisfy him, he erases both.

Readers might well ask where hope is found inside the darkness of Jekyll and Hyde. Suicide is not a good ending for anyone, real or fictional. Characters and real people don’t get much more hopeless than believing life is better without them. Still, we should think twice before dismissing Henry Jekyll or Robert Louis Stevenson’s allegory. If we throw Jekyll and Hyde away as just another piece of “classic” literature with a downer ending, we will indeed miss the hope and brighter themes found within.

Hope exists in Jekyll and Hyde first because it is an allegory. Jekyll and Hyde are not simply characters bending to an author’s whim. The secondary characters around them, such as lawyer John Utterson, are not cardboard props. These characters are stand-ins for complex concepts like good and evil, or if you prefer, certain moral alignments. For instance, John Utterson could be read as lawful good. Dr. Henry Jekyll could be read as someone whose alignment evolves; he begins as lawful good or perhaps neutral good, someone who would do the right thing regardless. However, as Jekyll’s physical and mental state deteriorates, so does his alignment. In unleashing Hyde–pure chaotic evil–he becomes increasingly unable to balance his actions and reactions. No matter what moral alignment they choose though, the novella makes clear characters always have a choice. If they choose wrongly, we can and should mourn that, and take it as a lesson. Still, at various points, there are opportunities for Jekyll in particular to make a different choice. This idea of humans using free will, choosing what to be and become, would’ve brought a timely reminder and plenty of hope to Victorian readers. In a callback to evergreen themes, the idea of free will may bring comfort today, as the world becomes increasingly chaotic.

Additionally, Stevenson’s story gives readers a sense of hope because its events are not possible. Remember, both Victorian and modern readers live in worlds where technology appears to take over more every moment. Anything seems possible, even advancements that might herald humanity’s downfall. But Stevenson reminds us, we have not yet reached the point where people can split themselves. They cannot eradicate their bad sides completely, nor can they make themselves humanized angels. People can only be human, good and bad in the same bodies and minds. Thus, Jekyll and Hyde exhorts readers to be the best humans they can be. Stevenson invites us not only to examine our dark sides, but be grateful for our light sides. He and his story ask us to indulge the light as much as possible. Of course, this is not to say that every human who gives in to the darkness will get out of control and commit suicide. Similarly, not every human who tries to be “Jekyll” as much as possible can avoid “Hyde” moments forever. However, self-control and exercise of good impulses can make us stronger, better people.

Closing Notes

The Victorian period was one of the longest in literature, and gave readers some of the most memorable novels in the Western canon. From diehard bookworms to reluctant readers, every Western reader has been exposed to at least one Victorian novel or novella, and learned something from it. Many readers return to Victorian novels again and again, citing them as old friends between the covers of a book or e-reader.

Victorian literature possesses several elements that set it apart. Perhaps the best part of it though, is how well it manages literary dichotomies. Maybe more than any other subtype, Victorian literature gives readers evergreen genres and themes to explore, while remaining true to its time period. It introduces readers to characters who might seem overly simplified but who encapsulate the truest parts of human nature. Victorian literature also does a wonderful job balancing the dark and macabre with the hopeful. Readers find this balance encouraging, making Victorian stories true classics.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

From what I can tell, the best of Victorian Literature has an extraordinary flexibility in that the main idea of the plot is comprehensive and easy enough to understand, but the more you drill into the plot, the more nuance you find. You did a good job of illustrating this. Well done!

You’re right, and I love nuances and complexities. Maybe that’s why I like Victorian literature so much. 🙂

Jane Eyre is a wonderful novel. It was definitely the first work of Victorian literature that I read that I reeeeally loved. So, I recommend it to anyone who might be unsure if Victorian lit. is for them.

There are a few on this list that I haven’t read yet, but I am certainly keen to. Great writing as always. 🙂

I love Jane Eyre so much. I first tackled some of it when I was about ten (it’s a little heavy for a kid, even a rabid bookworm like me). Later, I read it through for pleasure and for a class. The class made it less “fun”–the professor basically responded to all my analysis with, “So what?” But it is one of the best Victorian books out there IMHO. Jane is one of my literary soul sisters, and I always enjoy spending time with her.

Loved jane, loved the writing style but absolutely hated the love story.

I get that. Rochester is not in any way what 2021 readers consider a healthy person to be in a relationship with. I’m still torn over whether Jane should’ve remained single, especially because Rochester was disabled in the end and she basically became his caregiver. I don’t like what that says about disability in the Victorian era, women as “angels in the house,” etc. But the book is well worth the read–or reads–just for Jane.

It’s easy to call this book a love story, but it’s really much more than a simple love story. While Jane Eyre longs for love from the very beginning, she doesn’t accept it easily when she actually gets it. There’s a constant struggle between that and her autonomy.

A Little Princess reminds me of how Disney has spoiled the term “princess.” A princess isn’t one who simply is spoiled but one who is steadfast, wise, and generous. It’s not someone to dress up as, but rather someone who deserves to be imitated in thought and action.

Amen to that. Now, I do think some princesses are better/stronger than others. Belle, Mulan, and Tiana will always be favorites. But yes, “princess” has become watered down and a lot more centered on looks and passivity than I like.

In a world filled with vapidity and superficiality, we need more writers like Frances Hodgson Burnett, who was a century ahead of her time in subverting the princess trope and making clear that bravery, kindness and generosity are far more valuable than family connections or wealth.

Yes! I loved her as a kid, I love her now, and I wish she’d written more books.

Fills my heart with warmth and joy.

It is essentially a fairy tale of the best kind, one that more children should be reading.

Generally I’m not a fan of the ‘classics’, but for Sherlock Holmes I make an exception.

I think we all do. Despite this article, I don’t sit around reading classics, either, but some really do stand the test of time. Sherlock is a great example.

And this one is the best one. I particularly liked reading about the moor. The way it was described made it sound almost alive, and ti was a really cool setting for the book.

Which Charles Dickens books should I read? Give me your favorite(s).

Well, Oliver Twist and A Christmas Carol, obviously. 🙂 Outside of those, try A Tale of Two Cities or Nicholas Nickelby.

I think David Copperfield is a wonderful book. I reread it recently, and I was struck by how funny it is, almost every paragraph has a comic aspect; but also how much darkness lay just behind the bonhomie. Mr Micawber, for instance, is comedy gold; but he has no hesitation in preying on his friends’ good nature to back bills he can never repay.

But mostly I love it for the incredibly weird incident when David and his aunt first visit the lawyer. Uriah Heep holds the horse while they go inside, and when David looks back he sees Uriah mysteriously blowing into the horse’s nostrils, like he’s casting a spell. But such is Dickens’s genius, that even Uriah has moment where he explains how his treatment by his betters made him what he is…

One of the really interesting things about David Copperfield is the way the narrator keeps doubting his own story by saying this is how he remembers things, but his memory might be wrong – it’s a sort of postmodernism 100 years before it existed.

Pickwick Papers. Nice, episodic structure suited to fluctuations in focus by a dwammy reader. Funny with nice character studies and place studies that took me back in time to a place and a people I never knew.

Great Expectations, or, if you’re up to a longer novel, Our Mutual Friend. The Pickwick Papers is the one I need to read. Hard Times is predictable, and lets readers see how little Dickens knew about the working class. It’s also the Dickens novel faculty repeatedly shuffle into Victorian literature classes. A Tale of Two Cities and Barnaby Rudge have their moments, but are both as reactionary as all get out. I’m a huge Dickens fan, but why people love David Copperfield is beyond me.

Depends whether you’ve read any Dickens before. Bleak House is his best , Copperfield the easiest to read, Great Expectations has a relatively simple story with fewer minor characters and Barnaby Rudge his most underrated. Just my ‘umble opinion however.

You will not regret reading Dombey and Son. Bonus for those heavily invested in the idea that Dickens couldn’t write women: if you can read it and still disparage Florence, you are a paragon.

Hard Times. Manageable length. Amazing history lesson. Poignant reminder of what people have lived through and how societies manage to learn; communities, blossom.

What about Dickens’ most neglected novel? Barnaby Rudge? It’s also one of his wildest.

I read this for the first time in April and agree. Fascinating novel…and it’s descriptions of how to incite a mob and the various motives of those doing the inciting remain painfully relevant.

Barnaby Rudge ~ it’s a wonderful book and deals vividly with civil unrest on the streets of London ~ most timely!

Wow. Oliver Twist seems a lot darker than the musical I grew up with.

Oh, yeah. The book is so dark that when I first read it as a kid, I was like, “When is this kid gonna catch a break?” But when you get past the gritty environment and the relentless tragedy (and it is relentless), you find Dickens has a lot to say about poverty, how humans are treated vs. how they should be treated, human nature, and so on. Thus, it’s a valuable book if not always an escape.

I find it comforting that no matter what happens in my life, there will always be more Victorian novels to read.

This isn’t a novel but I’d like to recommend, to anyone who hasn’t read it yet, Daniel Pool’s WONDERFUl guide to Victorian literature: “What Jane Austen Ate and Charles Dickens Knew: From Fox Hunting to Whist—The Facts of Daily Life in Nineteenth-Century England.” It’s easy to use and he thoroughly and entertainingly explains subtle stuff like who goes in first to dinner, and why the oldest sister is Miss Bennet and the second oldest is Miss Elizabeth. And it’s broken up by topic so you don’t have to read the whole thing (although you can), you can just look stuff up as you need it.

So good article. Im studying a course at univeristy just now called Victorian Literature and Culture. The book im reading right now is Adam Bed by George Eliot. Next week im reading Tess if the D’Urbervilles. Anyone read these??

Thomas Hardy (author of Tess), is a personal favorite. His writing can get a bit tedious, which is true of most Victorians, but it’s worth it! Tess is a great choice.

Can’t say I’ve read Adam Bede. I did read and enjoy Middlemarch by George Eliot, though. I’ll have to check out Adam Bede!

I’ve been thinking about a reread of a Oliver Twist. I got a free Audible Original called Dodge and Twist which made me start longing for the Victorian writing style again. But I also want to do the Group Read on Rachel Ray so Dickens will have to wait.

OK, so since I am not from an Anglophone country, Dickens was always a part of that ‘recommended’ school literature, and since it was not obligatory, I clearly did not read it. After reading this article, I have decided I am riped enough to take it on. Oliver Twist next.

The Hound of the Baskervilles is the first Sherlock Holmes book I read and I was very surprised by how much I enjoyed it.

I don’t like scary books and had been avoiding this book for years. At first, I found the book a little slow but it quickly picked up and I got involved in the story and trying to solve the mystery as I was reading.

As my first entering into sir Conan Doyle’s world : NOT BAD AT ALL!

Jane Eyre has definitely become one of my favourite main characters in a novel, and despite the year in which this novel was written, she can still teach quite a few lessons on girl-power and independence to current YA novels heroines.

It is most definitely still alluring to all high school teachers.

Because I didn’t read Frances Hodgson Burnett’s books as a child, I couldn’t really connect to them now as a young adult. I wish I could.

I loved little Sara Crewe, her manners, her independent character and rich imagination. Completely adorable and charming.

This was a good stroll down memory lane…. i remember watching the A Little Princess cartoon and the film years ago… it’s been one of favorite book during my teenhood.

Recently read Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde for the second time. I enjoyed it more and grasped it better this time around. Its one of my two favorite Stevenson novels, along with Treasure Island.

Oliver Twist is simply breathtaking, it accurately describes the situation of orphaned children in Victorian England of the nineteenth century.

A Little Princess is an absolutely beautiful story of the inner strength and virtue of a child. This is a wonderful picture of a true and beautiful character; someone to imitate.

I think that Doyle’s short stories work much better than his full-length ones.

I have loved Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories since I was a child & am still amazed at how good they are, even more than a 100 years after they were first written.

Such a dark, gritty, and depressing world which dwelled by poor Oliver.

I usually enjoy classics, but with the case of Oliver Twist, I super struggled to get in the first half of the book, I just couldn’t stay focused on the story to then enjoy the second half.

Just finished Oliver Twist. I was totally not expecting Bill Sikes to murder Nancy, nor was I expecting Rose Maylie to be Oliver’s Aunt!

I love it. So many exciting things happen in this story that actually make a pretty good book!!

I do really like the eerie feel of this Holmes tale, and would say it’s probably one of my favorites.

I think it’s very atmospheric and eerie, I didn’t really find it scary but the mood was definitely set!

Me too. I love the atmosphere that was set in the book. the foggy village, the did they really see what they think they saw, the folklore and urban legend almost of the Hound of Baskervilles.

I love love love A Little Princess! Such a beautiful tale of a young girl! Of course, the father\daughter relationship made me sob in parts, but I loved it! So beautiful, pretty and innocent!

Nothing ruins a book like having to read it for school. That’s my relation with victorian novels.

Great article. I vaguely recall reading “The Hound of the Baskervilles” in my early teens.

This is an undisputed classic.

It can be argued that the Victorian era was the first time the literary world indulged in genre. In the past there was non-fiction, moral fable, and religious, with the latter two sometimes merging into one. Here there was the birth of variety, and enough of it to supply multiple works within each genre. Its a fascinating boom of drama and intrigue and mystery that that took old concepts of storytelling, but adapted them in “modern” ways.

Great article! I completely agree with you on everything that you have said. The elements of Victorian literature that you have pointed out are exactly the reasons why they resonate with me, in particular. Thank you!

I wonder how it is that we have strayed so far from character driven novels, where the complexities of characters are no longer as important that the drama of the plot. Charles Dickens was a master character builder, which is one of the reasons why I love his writing so much.

Let us plea for a return to this golden age of literature, where the content of our modern novels may therefore resonate with us like these classics do.

I agree with your point that the genre is relatable for how it typically eschews simple good/bad dichotomies in favor of exploring the nuances wherein both the good and bad can (and do) exist within one individual. Because that is, essentially, a timeless question. Particularly re: Jane Eyre and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, asking: how is a person to come to terms with their darkness? Or, perhaps more accurately, how is a person to accept and make sense of the fact that there are both elements of light and dark that reside within all of us?

One aspect of the genre which supports these explorations is the focus on the character’s inner monologues and musings, giving the reader a peak into the psychology of a character grappling with their sense of self in these ways.

Very insightful article! I remember reading that ‘Strange Case’ was the result of a nightmare Stevenson had, one he recorded upon awaking. After allowing his wife to read, she remarked how horrible it seemed, causing him to throw it in the furnace. Later she said she wished he hadn’t done that, causing him to essentially rewrite what we know today as the final product.

This vignette makes me wonder if Stevenson was just as shocked as Jekyll that such abominable concepts can be born beneath his subconscious. Just as perhaps everyone tries to bury the monster they don’t identify with. Again when studying Jungian psychology, one can find that, as you said, and likely as Stevenson understood, that the solution doesn’t have to operate under dichotomies. We can acclimate ourselves to the existence of our shadow; not let it go unnoticed nor let it spiral out of control. With practice and with no judgement to ourselves in the process, we can resolve the Hyde’s within us all and not let them destroy us in the process.

Well done. The Victorian literature integrates psychological and sociological processes otherwise suppressed or not fully explored in pre-1800s literature. I would love to hear what you have to say about the Bronte sister’s styles.

Great article! I think Sherlock Holmes is one of the best examples of the “evergreen” quality of Victorian literature, as there are such an incredible amount of remaking’s and adaptations, and yet it still remains popular. Thought Dickens and A Christmas Carol might be a close second though…

Thanks! I tend to come down on the Christmas Carol side of the argument; it’s been a big part of my life since I was a little kid. But Sherlock Holmes is an absolute icon, and he will never not be cool.

Victorian literature has always been of great interest and love to me because it takes me to a different time and I have a greater understanding of the time and the stories that people were interested in and wanted to tell. It’s a great way for me to combine my love of literature and history.

I agree with your observations in this article. I think the thing that surprises me the most is that, for example, Jane Eyre (or other pieces of Bronte’s corpus for that matter), still has a solid “fan” and reader base that produces things like fan-fiction and fan-art.

Excellent article on Victorian literature. W

I must admit to a love for this period too, and for the continuing nostalgia of literature set in this period. I absolutely would not want to have lived during the reality of then, but it was a period of great dichotomies that always make for interesting stories. Thanks for the article Stephanie!

Amazing article! I love reading Victorian literature and reading about it.

I enjoy the concept of ‘evergreen’ literature explored here. It’s certainly true that certain novels continue to be reread and enjoyed even once their particular social framework seems outmoded and no longer relevant, and it’s great to see how you’ve dissected these novels for the plots and character traits that bridge this divide. I especially liked the comparison between ‘working from home’ and Victorian workhouses.

Victorian literature and the Gothic aesthetic go so perfectly well together but I especially like the pieces when their issues of the regressive Victorian society are addressed while the aesthetic is being appreciated.

Indeed, the Victorian era was such a fecund period that gave birth to new things to grow into Modernity. In terms of literature, it gave us the genres we love even today: realism, fantasy, children’s lit, crime fiction, sci-fi, Gothic … This is a great article to explore the greatness of Victorian literature!

Oliver Twist reminds me of my schooling days… Yes, it’s complicated but they made us understand it

I absolutely adore Victoria’s writing, I’m definitely looking more into classics!