Video Games and Morality: The Question of Choice

There is an important question with regards to morality in video-games: how does a game developer successfully implement the complex and dynamic idea of morality in a video-game? Further, how does this implementation affect the player? Is the morality imbued into the narrative, the mechanical gameplay, inside the player’s own mind, or a combination of all three? This issue is both complex and nuanced; I can only offer a basic summation of what I have experienced in the following video-games. Hopefully, many readers will continue the discussion in the future.

Beyond Good and Evil

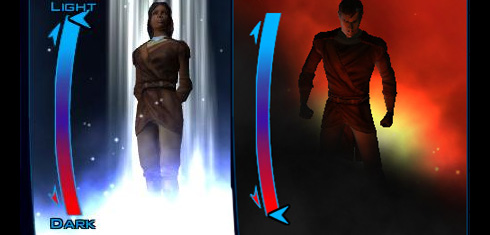

The classical mechanic of displaying morality in a video-game is through a single axis in which good sits at the top and evil sits at the bottom.

The player’s choices move their slider up or down the axis to show their overall moral being throughout the game. Early 2000’s Bioware games feature this mechanic, such as Jade Empire (2005) and Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic (2003).

Having this mechanic begs the question: is morality so simple? Reality is more complex than simply a split between good or evil. Every potential choice you make in life has both positive and negative effects, for you and for everyone the decision affects. It is your decision and responsibility which choice to ultimately make. This being said, most would agree to a rough idea of what is good and evil. There are choices that most would label as good, with other choices labelled evil.

Modern video-games have attempted to show this more complex and nuanced view. Games such as Bioware’s Mass Effect series, Telltale Games’s The Walking Dead (2012), and Lionhead’s Fable series (2004-2010) have done more with their morality mechanics than just keeping with the classical good vs. bad spectrum. Moral choices are instead left to the player to deal with, as they result in changes to the gameplay and narrative.

Despite these effects, it is important to understand that moral choices do not occur fully within the game, but within the player. Thus: “The line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.” (Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago). The game may present choices to the player, but it is the player herself who presses the button, who makes the choice.

Why Players Make Decisions

There is a level of ambiguity here: how can we know what the player’s motivations are for a specific choice? It would be easy if every moral decision a player made in a game was the result of her moral convictions. However, this is not always the case, since a player could feel no level of immersion or attachment to the game and its world. She recognizes the games artificiality and realizes her choices do not matter. As a result she may experiment with in-game choices out of curiosity rather than moral conviction. This result is universally undesirable for developers who wish to have the player think over her choices in a meaningful way.

Instead, developers will emphasize immersing players in the secondary world of the game, becoming an active participant. The player becomes emotionally invested in what is happening onscreen; she may hesitate to make certain decisions, or feel remorse or satisfaction afterwards. The game feels real to the player because the world exists in that moment of playing. Moral choices thus carry a weight similar to real world choices, despite affecting a secondary world.

The Balance Between Order and Chaos

Bioware’s Mass Effect 2 (2010) introduced a simple yet incredibly effective game mechanic with regards to morality. The game’s predecessor had two meters, paragon and renegade, which would independently fill up depending on choices made by the player. Bioware was smart to avoid the use of the words good and evil, and to keep both meters independent of each other; they very clearly indicated that you character was not simply good or evil, and didn’t simply make good or evil decisions. The sequel added a new mechanic: during cutscenes, a paragon or renegade symbol would flash on the screen (akin to a quick-time event) prompting the player to take action. These usually served to interrupt a non-player character’s dialogue or actions, requiring knee-jerk responses from the player.

What is notable about these quick-time reactions was that they were not always reflective of a good versus evil dynamic. Instead they often reflected a decision between order and chaos. The paragon decisions usually coincided with the character acting reserved, controlled, and fair. Conversely, the renegade decisions coincided with acts of impulse, frustration, and a “shoot first, ask questions later,” type attitude. These are decisions that people face almost every day, and are reflective of a more ambiguous interpretation of morality.

It is neither effective to live fully in order or chaos. To live under order is to deny oneself the liberty of making choices, they are already decided for you. Totalitarianism expresses this idea. However, to live in chaos is to forgo any measure of safety, resulting in a harsh and unforgiving world. The consequence of these extreme world views is a loss of individual liberty.

It is the balance of order and chaos where living is made whole; the mediating of both sides. Here lies the beauty of the paragon and renegade system being exclusive of one another; they are not wholly an issue of good versus evil, but of order versus chaos.

Show, Don’t Tell

2k Games’s BioShock (2007) creates this sense of order and chaos within the mind of the player herself. At many points in the game, the player is given the choice to cure the “Little Sister” characters or to harvest them. By curing them, the “Little Sisters” revert to a state of normalcy; they become freed of the parasite which grows inside of them. By harvesting them, the player kills the “Little Sister” in order to receive more in-game resources. There is no meter in the game to show the player whether they have made a good or bad decision. The full effect on the narrative is only shown during the last cutscene of the game.

The game does not tell the player whether her decision will be right or wrong. Instead, it is the player who must weigh the impact of the decisions and make a moral choice. The outcome of the decision affects the gameplay with regards to resources gained, affecting the player mechanically. Beyond this, the act of saving or killing a girl affects the player morally. This asks the player to question her values: sacrifice morality for in-game advantages or uphold morality at the cost of new potential abilities.

The salient point is that BioShock imparts a deep moral choice on the player using so little; the image of the “Little Sister” with her fate displayed on either side

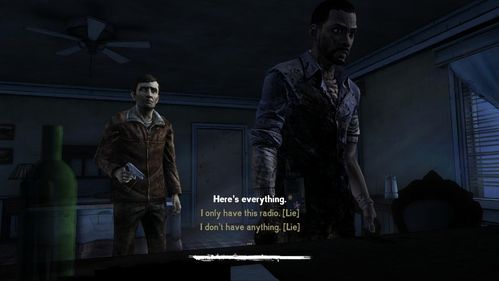

Telltale Games’s The Walking Dead (2012) also manages to avoid telling the player whether her actions are good or evil. Throughout the game the player must make hundreds of choices, from seemingly insignificant decisions to deciding whether a non-player character is left to die. The consequences of the player’s actions are almost never clear, and when they are the relationships the player has with her allied non-player characters strongly influences what she should do.

The narrative of the world helps add to the ambiguous nature of these decisions. Civilization has collapsed, the world is a dangerous place, and resources are scarce. The player has to make decisions for what is best for their character, while also trying to decide what is best for: non-player characters she cares about, for the group, and for all survivors. This balancing act puts weight on the player, and asks her to question every decision she makes no matter how mundane.

This design approaches a level of realism missing from the classic morality mechanic. Decisions are not grouped as good, evil, or even neutral. They are dependent upon the player’s experiences and relationships, upon reacting to difficult situations where answers are not sudden. This in turn creates a more immersive experience which can stay with the player long after the game is over.

Use Your Illusion

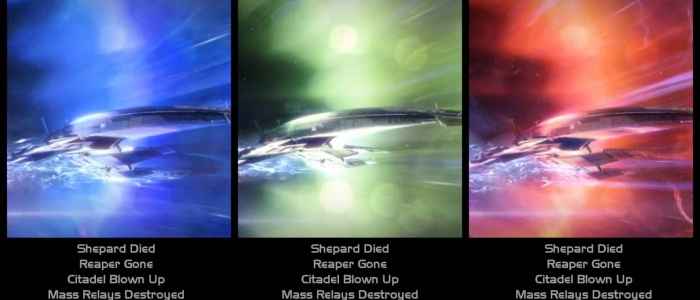

The question of how moral choices affect the ending of a video game became a topic of conversation after the release of Mass Effect 3 (2012). Many fans of the series voiced their disappointment with the level of triviality in the three different endings to the game, or in other words a lack of meaningful difference. If the consequences of a decision feel identical or trivial to a player, then she loses immersion (the necessary element to moral choices having weight).

The ending of Mass Effect 3 became an internet meme as a result of its negative response. Each outcome was dubbed “blue, green, or red,” by fans to jokingly point out the only real difference between any of the endings. What does this emotionally charged reaction say about player immersion and emotional investment? I argue that choices which lack immersive qualities will sever the player’s emotional investment. However, consequences to moral choices which have a significant impact are not necessarily the only way of accomplishing immersion (remember that The Walking Dead‘s approach of ‘quantity of choices’ versus ‘quality of impact’ led to more nuanced and realistic relationships between the player and non-player characters).

May the Force be With You

Obsidian Entertainment’s Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic II The Sith Lords (2004) subverted the very nature of the Force, a common element in the Star Wars mythology. To reiterate, the original game featured a meter that the player would move up and down on depending upon their decisions. At the top was the light side, at the bottom the dark side. While the second game maintains this classic mechanic, it presents a character who subverts its simplicity.

Kreia acts as teacher to the player’s character throughout the game. As the player character makes moral decisions reflecting either the light or dark side of the force, Kreia often provides a commentary on this simple view of morality. She very directly criticizes the duality: “I cannot force you to listen to reason, only hope that you will grow past these infantile delusions of right and wrong.” (Knights of the Old Republic II, 2004)

How interesting that the developers would choose to include the classical morality mechanic in their game, yet also have a character which undermines the nature of it. Further, Kreia’s insights serve to undermine the entirety of the Star Wars mythology with regards to the Force.

The End of all Things

Video-games present a plethora of ways to explore morality. The complexity and nuance of morality presents a challenge to developers everywhere in how to elicit emotion and how to convey a sense of weight to important decisions. Hopefully after having read this article, others would be inspired to investigate the games that they have played and question how morality functions within the game world. Video-games such as the Fable series, Deus Ex: Human Revolution (2011), Dishonored (2012), and many others should be examined closely with regards to how developers implement morality, and what effect this has on the game world and player. Perhaps one could look into the history of philosophy on the issue of morality, into the works of James Rachels and Friedrich Nietzsche, to name a couple. Morality is a deep conversation embedded in video-games, a conversation that perhaps has no end.

Works Cited

Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr Isaevich. The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, 1918-1956. Translated by Thomas P. Whitney. New edition edition. New York: HarperCollins Canada / Westview Pr, 1997.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (John Ronald Reuel). The Tolkien Reader. [1st ed. ]–. 1 vols. New York: Ballantine Books, 1966.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Best realistic moral system game I’ve played goes to spec ops the line. There was no good or bad, just decisions.

Wish it was more common to create hidden third options. I was kind of annoyed in Skyrim because there is this one beggar in Windhelm that you can give 1 septim like anyone else, but even though she complains of the cold, I could never give her a set of clothes enchanted with a total of 100% frost resistance. It would have made me so happy to have actually done something that meaningfully made this character’s life better, when you don’t even see any effect on them for giving them that gold piece and doing so is trivially cheap.

I can vividly remember trying to give a beggar in Skyrim as much money as I could. Just like you said, I think you could only give them 1 septim at a time. It was rather disappointing that nothing ever came of it, but it is quite silly to think about the implications: some beggar in Skyrim became rich yet is pathologically continuing to pretend that she is poor. Thanks for your comment!

Games don’t convince us that the world we’re in is real and that our actions have consequences. We know, even more so than films and tv, that the other ‘people’ are just programmatic objects that are loaded out of memory once the scene moves on. At least in TV there is significant development of character to make us empathise but the lack of realism or character development in games mean they’re all perceived us soulless objects.

Thanks for the comment; you have some interesting points. Immersion is a phenomenon that has been studied heavily with regards to film and recently video games (not too sure about television). As it turns out, for most people there is a threshold that games cross whereby they lose sense of the world around them and become ‘immersed’ in the game world. Interestingly, music serves as a facilitator for immersion (at least that is a common hypothesis). I would recommend reading “Effects of Contingent and Non-Contingent Audio on Performance and Quality of Experience in a Role-Playing Video Game,” by John Baxa for some hard experimental data on this kind of thing.

I will grant that games are often better suited for environmental storytelling versus character storytelling; however, it’s rather subjective to say that all character development in video games is incomparable to film and television. I can think of many great examples. Also, there are plenty of bad examples of character development in television and film that take away from a sense of immersion; it happens within any medium.

I assume your comment is coming from first-hand experience? If so, I’d love to know what games you’ve played; I might be able to give you some awesome recommendations for games that have good writing and character development.

In my experience games yield a higher emotional investment than films or TV programmes.

I’ve never got annoyed if a character on TV dies, but I have got annoyed if something goes wrong (and happy if I complete something challenging) in games.

I was wanting to write an article on this topic but you beat me to it. This is really insightful and interesting.

I was happy to see you discuss the significance of outcomes and consequences regarding our moral choices. When our choices matter, as in, when they have an impact, they become a lot more significant and they validate the agency we seek to feel we have. We crave constant reassurance that we have control over our lives and destinies. This is why we are disappointed in games that don’t provide that reassurance.

I think it does trigger an interesting existential question about personal agency and lack of control in our real lives.

I read a blogpost or something on a website, that claimed one day we’ll have games where EVERY single action will mesh with the narrative. Hope we get there some day…

I imagine that would require some hardcore technology. But I guess anything is possible now that computers can beat us at chess! I agree though, and I hope we get there too. Thanks for your comment!

Seems to be going in that direction. RP games are allowing for multiple narratives and a kind of choose-your-own-adventure aspect to them. I would love to see games reach the point where it’s all-encomposing virtual reality with this element of total reactionary narrative playing into each and every decision the user makes. I can’t see why this won’t eventually be the future of gaming.

The Witcher 3 does an amazing job of presenting Geralt with moral dilemmas that can dramatically change the world as a cause of which solution you choose, and the most important choices are timed so you can’t just go look up the consequences or benefits of each choice. like in real life, you have to make a decision over a complex, challenging decison while trying to divine the possible consequences of each all in the span of a few seconds. however, Geralt is almost never giving something up, so for that I look to game number

This war of mine. instead of giving you a direct choice, this game presents you with challenging moral dilemmas through gameplay, as you are forced to constantly ask yourself how far you are willing to go to ensure your group’s survival. you could help people in the hospital by giving up meds, or give some homeless people food, but foods and meds are extremely valuable resources which could instead be used to keep your team alive. on the flipside, you can kill, steal and smash your way to all the materials, but that will itself make you accept that you are killing people to get just a few more resources than you could get just scavenging, and combat itself is a risk, as it kould kill your scavenger, or incapacitate them for a week or more. I only use stealing as a last resort, when I can no longer aqquire a reasonable amount of resources elsewhere, because I have to accept that even though it’s just a video game, I won’t kill someone who is not hostile to me immediately upon seeing me, and will only attack when provoked unless I have no other reasonable option for the survival of my group. now that was a really long post, thanks for reading the whole thing.

Witcher 3 had lots of very very hard moral choices to make, that in the end I wasn’t fully happy with, in either scenario, but still got the job done. Those choices (at least one of them) had me literally sit for 20 minutes thinking of what to do.

Witcher series pretty much nailed it when it comes to giving ambiguous choices. You will choose one thinking it is for the best, when later you find out the so perceived good choice led to the death of that NPC and his family!

I’d like to see more media in general handle morality better. It’s so rare to see a work where there isn’t clear good and evil (or at least characters/choices which the authors didn’t clearly intend one or another to be good or evil). Maybe once our society gets a better handle on ambiguous, gray morality in general, having better grays in video games will come naturally.

Papers please is of great interest here. You can deny citizenship to people who are pleading, focus on stopping or helping rebels or just focus your family. You don’t know that your making them until the end.

Excellent article. Great points well made.

Greatly appreciated!

I have two game series, Devil Survivor and Shin Megami Tensei that are nothing but choices. Each choice will either take you down the ‘good’ path, the ‘neutral’ path, or the ‘evil’ path. Each path actually has its own rights and logic as to why it is the right way. This makes it hard to chose because sometimes killing an already dying man might be the best thing before letting demons take his soul. But that’s down the ‘evil’ path.

Have you tried the core Shin Megami Tensei games? They focus on the choice of Law and Chaos and trust me, none of the choices the characters present you with are easy. Especially since there is no right or wrong. What it represents is simply your belief.

papers please did morality great

I agree, and they also managed to do so much with so little. The game can be boiled down to simply pressing “accept” or “reject”, and the implications and consequences are so far reaching. I’ve played through it so many times and the amount of little details just astonishes me. Thanks for the comment!

I don’t think there is anything wrong with the linear morality line, if there are rewards and a sense of purpose for sitting on a specific level. Morality is also subjective. Antiheroes are cool hybrids whose same actions can be interpreted differently by different players.

One example of a good moral choice. There is a side mission in the original Mass Effect where you find a derelict space ship, kept running by its automated systems, after exploring it you happen upon a clinicaly dead man kept alive by life support, I loved that bit, it was a great moment, one of personal belief and self reflection… what do you do? The best part was neither choice gave Renegade or Paragon points, and that was a master stroke.

Brilliantly written. I only get invested in games with a compelling storyline. The morality of choices in a video game is best conveyed in “this” or “that” decisions, rather than labeling them as “right” or “wrong.” Real life has a lot of grey, and it’s easier for a player to get absorbed in the world when it more closely reflects reality.

Video games is cool time killer, and its all

Thanks for the comment. I certainly have to concede that many games for me are time killers: agar.io, pac-man, flappy bird.

However, I couldn’t disagree more with you when you say that that is all they are. I wonder if either:

a) You just haven’t played anything you feel worth your attention (for literary, mechanical, or aesthetic reasons).

b) Perhaps they might have not been something you have given much thought to?

Even the games I listed above have merits on their game mechanics alone. Piaget, Huizinga, and others have delved into the nature of ‘play’ and ‘games’ in ways that changed how I thought about games, and video games by extension.

Let me know what kinds of game you have played. I might be able to recommend some that could change your mind.

Very Interesting Article! I hope Bioware’s upcoming Mass effect: Andromeda will have a moral choice system that fits somewhere within your article.

KOTOR is one of my favorite games so I was glad to see it in your article.

Cool stuffs!

I think darksouls does a good job with the whole morality thing. look at the chaos servant covenant, you gather humanity to give to the fair lady (quelaag’s sister) (quelaag being the spider lady you killed) to help her regain her strength after she drank blight pus to help some residents of blight town, this left her blind, mute, and immobile. it would seem obvious that you would help such i kind person until you consider how you get humanity, you have to kill rats, humans, and hollows to get humanity, then when you think about it, you come to realize that you are killing many people and creatures just to ease the suffering of one. now you think, oh, well that’s not right, i can’t do that, but then you find out that quelaag (the spider lady you killed who is the fair lady’s sister) was actually killing those who came into her domain so she could give the humanity to her sister, so the choice is, do you leave her to suffer after killing her sister who was just trying to nurse her back to health (or something close to it), or do you invade the worlds of other people kill them, take their humanity, and use the humanity to help the poor girl you condemned to suffer. there no real correct “good answer” to this situation, and that is what makes it such an interesting choice.

Came here to post about DS. DS has a lot of instances where the choices you make affect the story directly. making the story ambiguous and bot very descriptive has a tangible effect on the choices you make as well. Its not game altering, but the fact that it is present yet subtle makes the experience all the more immersive. Bloodborne does this perfectly as well.

I don’t really like choices that give me different areas cause if i replay i usually play the good guy and stick to the same choices

I feel like sometimes the player’s desire for narratives in which their choices have concrete consequences and impact comes into conflict both with the designer’s desire to tell a given story and, even moreso, the rapidly exponential cost that comes about when having to design around an ever growing matrix of decisions and outcomes.

the truth is you really can’t design a system where ‘every choice matters’. no matter how you look at it the game will always be confined to a pre-determined method to deliver its outcome and its assortments. Like you’ve said , that would be bloody expensive.

Really interesting discussions, thanks for writing this article.

About every Bioware & Obsidian game ever made nail the moral options, there wasn’t only a BAD-GOOD AXIS moral meter the NPC’s in your party and even the NPC’s populating those worlds would Like You More or Less depending on your choices, some members of your party would abandon you or outright confront you and try to kill you whenever you did something they would consider atrocious or in complete opposition to their own moral or amoral standings.

deus ex human revolution has some great moments of choice. saving malik or running away, the gas chamber problem in the dlc, they are great with choice in a way that i wish more games will be.

I have played both Walking Dead games as well as the Last of Us and currently, Grand Theft Auto V. When it comes to the question of morality, I find the spectrum used within all these games rather different.

Whilst the Walking Dead could be rather ambiguous on the whole good versus evil situation, the moral choices which decided who out of the good guys would be sacrificed for the safety of the group definitely made me think of how I would handle those situations in reality. Ultimately, saving one person killed another and opened up different game choices or a different path so I could never be too sure if it was the right thing to do.

The Last of Us was much simpler in terms of good and evil. The main characters are fighting enemies on all sides and it was rare in the game to come across truly well intentioned individuals. This was a kill or be killed scenario so the moral choices were much simpler to make.

GTAV is a different kettle of fish altogether. The characters are pretty abhorrent and it’s hard to find anything redeemable about them but then, there is something immensely fun about playing a character you can play merry hell with. The body count is ridiculously high and the open world set up allows you to go off kilter and behave in ways you would never exhibit in real life. I love it but I am an adult and ultimately, I know the difference between right and wrong.

The problem with ambigous moral choices is that there really is no satisfaction from doing what you perceive to be good if that good choice is ambigous enough to be bad. This is kinda why I find games entertaining.

Wow. What a deep take into this concept. These are all really interesting ideas that were great to see you look into.

Good article. It looks like a lot of work went into it. Fallout 3 and Fallout: New Vegas are two other great examples of the choice of morality in video games.

In some cases a game actively encourages not letting feelings get in the way of your power fantasy. GTA and so on – the biggest, loudest voice you hear in its defence is “it’s not real”, “it’s just a game” and “it’s cathartic.” If you’re playing the game to feel powerful and do appalling things in a safe virtual space, guilt isn’t going to come anywhere near that. No judgment there on my part, it’s just how I see it. Games where you’re supposed to feel powerful and in control don’t set out to make you feel guilty for doing bad things.

On the other side, a lot of games have very thin and uninteresting character writing which makes it difficult to get really engaged in the cast. Most war games don’t have interesting enough casts, for example, to tell interesting war stories – so you get reheated scenes from all the best war movies like “you can only save one guy” or “the rookie dies” or “never leave a man behind” but it’s just going through the motions. For all the authorial intent is to tell serious stories about war (and if you read the endless interviews with the people who make Battlefield/COD etcetera, who genuinely believe that they’re writing worthwhile and new stories) it never works too well.

Not the best example for morality in games but, in GTA 2 there is a very clear respect meter for the 3 main gangs per section. This article made me think of that

Brilliant post!

Honestly, my most memorable experience with a “morality” system of sorts was Nier (the first game for PS3).

If you haven’t played it, I’d honestly say it’s worth buying a PS3 and a copy of Nier just for the experience. As a game it’s hard to get into, but stick with it through to at least the first ending (preferably the others too) and holy crap is it one of the most powerful gaming experiences I’ve ever encountered.

Anyway, most of the choices are as a result of side quests. The quests themselves are monotonous and very fetch-oriented, but the world that Nier builds and the extent to which it succeeds with making EVERY character feel human is almost heartbreaking. The quests and rewards are crap – you’re motivated by the interactions with the NPCs.

The “morality” part is a simple one – in certain quests you’ll learn a piece of information which you can choose to tell to the relevant party, or to keep your mouth shut and just finish the quest.

There’s no meter tracking your choices, there’s no indication of what’s right and wrong (all choices have pros and cons), and multiple times after finishing a quest the main character wonders out loud if they did the right thing.

The game itself doesn’t really change in a lasting way – the only effect of the choice at all is a lingering sense of worry/guilt/dread with the player, letting them stew in the potential consequences and downsides of their choices.

I can’t describe it well enough to give it proper justice (and I don’t want to spoil any of the choices for potential new players), but I’d urge anyone seeing this to give it a try if you’re interested in different (and better) ways to handle morality in games. 🙂

Thank you so much for your reply!

While I haven’t played Nier, I did watch Super Bunnyhop’s video about it which was excellent and has me very interested in both the original and the upcoming sequel.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j8xx4sT6rEI

Just a fair warning to everyone, I believe there are spoilers in the video (If so I think he warns you beforehand).

I’ll have to check that out! (After getting the final ending for myself, of course) 😉

Aye, highly recommend both Nier and the Drakengard series (1 & 3 are better than 2). They’re from the same creator/director (he also worked on Nier: Automata with Platinum) and are all fantastic examples of bittersweet, melancholic, dark fantasty. 🙂

That sounded much more appealing in my head…

You’ve put together a very interesting article about choice systems within video games, although I was hoping you would touch on games that allow you to create characters with moral dimensions. Video games adapting Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) rule sets often allow the user to designate their character(s) as good, neutral, or evil and lawful or chaotic. This system is more complex than the simplistic binary systems you critiqued but may also lead to fewer decisions based on morality. Throughout the course of a D&D-based video game, a user can try to align their choices with their pre-made character’s moral, but they don’t have to. They may choose to make decisions that provide more utility, to explore different consequences, etc., instead of aligning with their character’s values. This can lead to a more complex decision and it falls on the developer to create meaningful decision trade-offs and consequences. This can be a tremendously challenging task even for a game with a simple morality system, as you recognized in the lackluster endings for Mass Effect 3.

The most complex morality- choice system I have encountered in a video game has been in Divinity: Original Sin. While the game mechanics and rule sets undoubtedly draw on D&D rule sets, the choice system consists of multiple binary morality traits that are not pre-chosen. Instead of a light-dark or paragon-renegade meter there are several binary traits including, altruistic-egotistical, righteous-renegade, compassionate-heartless, and forgiving-vindictive. Different decision can increase points in one direction or the other and if a user chooses enough consequences in one direction their character is rewarded with bonuses. Interestingly, there are no bonuses for balancing the two ends and remaining in the center. The challenge for a user is one that you have already pointed out, it can be difficult to determine how choices will impact these values for a given choice. Divinity, arguably gets away with this ambiguity because it’s a very complex game with a steep learning curve, so we can rationalize the choice system ambiguity as being a part of the challenge to understand the game and its rules.

Interesting, well-researched and well thought-out article! I appreciate that you spent some time discussing the Mass Effect trilogy’s morality systems. Has anyone started Mass Effect:Andromeda? I have only played a few hours so far, but the choices provided are much less binary than in previous Mass Effect games, and I’ll be interested to see how more complex choices and interactions influences the plot and/or ending. Based on reviews, these choices don’t add up to much, but I want to see and judge for myself.

I would like to see more progress in this field in respect to games

Nice article – I am curious how game developers decide their views on how their morality systems are generated. There seems to be a distinct perspective difference between games that use active morality systems that are defined by good or bad as opposed to those who use passive morality where the gamer must choose for themselves. It is also interesting how most people in the comment section state that they have more memorable moments with games that have passive moral choices as opposed to that of active, defined ones. I suppose it goes to show that morality isn’t cut and dry, but just a grey fog.

I think it is worth exploring how games with active morality systems often have completion achievements to play both sides of the moral coin, as well as the fact that choosing the different moral positions in these games often brings different powers. In the case of the ‘Infamous’ series, choosing the Infamous path gives the player character more destructive power as opposed to the Hero path. Why does evil have this connotation with violent, destructive power? It’s easy to say evil is always destructive, but is that always the case? Is there ever the case that a Hero has to be destructive for the greater good? It could be something to think about.

In video games the players are left to explore and tweak this virtual world to their own personal world. They essentially leave their connection with the real world and throw themselves into what they have created. In this world they are free to make any immoral decisions they please. The fact that it is their world reinforces the idea that they don’t have to abide to the rules that are in our society. Choosing to kill someone when the shouldn’t or not help somebody in need is a decision much harder to face in the real world than on a screen. This major difference between worlds is the reason people shouldn’t be scared of the influences of video games. Once the are done fooling around in their virtual world players “return” to reality and no longer have the desire to make the same immoral decisions they did in the game. Video games should be seen as a source of emotional relief for people to work out the darkest corners of their mind.

As much as VR is growing so are all these choices and now they are immersive as well.

I feel that it is much harder to be ‘evil’, or more accurately, selfish, in video games. No matter what RPG I play, I always end up being lawful or good because I feel that it offers the most content and I want to play the most out of a game. I could choose to just kill an innocent NPC but then it will end the quest chain. Consequently, I am ‘good’ for selfish reasons.

Morality systems in games are always interesting in the ways that they are implemented. It is incredibly easy to make them irritating or effectively useless for the players, but a well made one can be a great asset to a game.

As a massive fan of the Mass Effect franchise I always loved the way the game let you choose what type of hero you wanted to be: do you want to be the knight in shining armour that saved damsels in distress? Or do you want to be the more pragmatic hero that did whatever it takes to get the job done? It allowed for so much replayability that I’ve finished each game in the series multiple times. But one thing that always bugged me was that if you wanted he optimal experience for your character, virtually, you were forced to stick to always being good or always being bad which really limited the effect that a moral system in a game is meant portray. You would always want to stick to one morality since it unlocked powers and more dialogue options to use in conversation and negotiation so I rarely changed my moral choices during the game, unless it asked you which character you essentially wanted to be killed off.

I personally don’t think the concept of morality should be put in games. I mean the whole idea of games is to escape reality. And I believe that large developers understand that. That is why you see games like GTA becoming more and more popular even though it has no morality whatsoever. This keeps players hooked as they want to delve into this different world and escape the reality which they are in.

For me personally, the act of violence in a game has never influenced any of my real life decisions. I do believe it desensitises children and adolescents to forms of fantasy violence. However, I find it hard to believe it would have any lasting impact on their real life attitude towards violence and brutality. Part of the fun in RPG’s is the ability to make ridiculously irresponsible decisions in a make-believe world without real world consequences. We should always implement a moral code in whatever we do, we just need to assess the context in what we are applying it to.

Personally, I enjoyed the factional morality system of Dragon Age: Origins. No action is either strictly good or bad, but each action generates approval or disapproval with other characters, depending on their personalities and moral views. This mechanic added a level of depth to the choice mechanic, as there is no way to make everyone happy, and everyone has good reasons for holding the opinions that they do. Some games that work with a decision mechanic present laughable extremes as the only options available. DAO makes things more nuanced by giving more dynamic responses to your actions.

This was an excellent read! I am current writing a dissertation for my Philosophy degree on morality in the virtual world and this touches on some core themes that I am writing on. Fantastic work!

Loved this article. I think it’s a very important time to discuss morality in video games. Although developers should be able to express their creativity, it’s important to consider the implications of a player’s in-game actions on their daily life decisions. With VR and robotics rapidly growing, we need to start thinking about the ways that innovation and morality intersect. Just because we can, should we?

I am currently in the midst of trying to complete Dragon Age: Inquisition and this is a topic that has been on my mind since I started this game. I feel like DAI deals with morality in a very interesting and complex way compared to other games I have played. As the main character, you interact with multiple different NPCs around you. Each main NPC has their own beliefs based off of their unique histories. This affects how they will react to decisions you make as well as things you say during discussions with them. This puts a twist on morality as, to my knowledge, it is near impossible to make everyone believe you are completely good or evil. Different characters will agree with the decisions you make/things you say while other characters will not. Really puts a reality spin into the game play itself! Heck, even to romance a character while you are ‘committed’ to a third NPC makes you break off the romance with the NPC you started the first romance with. Really interesting game play mechanics!

Also love that you included Bioshock and Fable! Interesting points there.

Another element that could be touched is in-game “rewards” for morality. I know in Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, it didn’t pay to be in the middle of morality. It was better to be very good or very evil. This would allow you to unlock perks that couldn’t be unlocked if you were in the middle of morality. It sucks because then the game forces the player to essentially pick a side rather than play it how they might emotionally want to , sometimes good and sometimes bad.

It’s why I praise Witcher 3 for putting so many moral dilemmas that don’t really impact the game other than the ending. I recall a moment when Geralt finds a massacred village and it’s because of another witcher. At this point, the player decides whether to kill him or let him be. If you let him live, Geralt recalls his past failures as a witcher and how he also has gone on a rampage so Geralt understands and forgives the witcher. I thought it was wonderfully written and puts an interesting dynamic on morality.

Fascinating article. I think morality is always something that will intrigue humans. As for games, on a base level they are definitely used to increase interactivity and create a greater bond between the player and the character. Khriistopher also made a great poinnt that some games give you ‘rewards’ for morality, but I wonder about games like GTA? Essentially the more psychotic you become the more rewarded you are with perks, trophies for brutality, and in-game materiality (such as money).

Another point worth mentioning is that sometimes morality has a huge impact on the game and narrative (such as in the Wolf Among Us) while other times its virtually irrelevant in the end-game (such as in Fallout or Skyrim). Returning back to interactivity, I definitely believe that when decision making has an outcome on plot, people care about their morality a lot more! Some kind of a reward is always at stake.

I recently penned an article for school about something along these lines. It examined Crusader Kings II: a medieval grand-strategy RPG wherein you lead a medieval noble family through the Dark Ages of Europe. It’s a grim world: war, chaos, violence, intrigue, disease, poverty, corruption, and betrayal are the norm. In these trying times, I argued that the game implicitly encourages players to act immorally as they attempt to survive. Many of the actions one may take in that game are blatantly evil: murdering children, mutilating prisoners, burning villages. But the game itself never passes judgement on you for it; it simply tells you how it worked out. It puts you in the mindset that what you’re doing is indeed wrong, but you should do it, since it will give you an edge over the myriad other threats you face in the world. It’s a brilliant way of working with morality in games, and an excellent case study in this topic!

one fantastic article.

great job

The main problem with most video game morality is the binary. You have to eat puppies or never have a bad moment ever in character. I did enjoy how Dragon Age’s first go of things but toward Inquisition it really felt hack.