Angela Carter’s Beauty and the Beast: Building a Feminist Romance

When it comes to fairy tale retellings, no story is perhaps more popular than Beauty and the Beast. Created in seventeenth century France, and later popularized by Jeanne-Marie Leprince De Beaumont, the tale continues to be reimagined again and again. Everyone, from French filmmaker Jean Cocteau to Walt Disney, has adapted this particular love story. Even today’s popular literature such as Twilight, 50 Shades of Grey, and Of Beast and Beauty seek to emulate it. While undoubtedly popular, Beauty and the Beast is also famous for its treatment of both male and female characters. Some claim that it is not a love story but instead a tale of abuse. Others say it is a story about female empowerment and the healing power of love.

But how are both these readings possible? According to fairy tale scholar Jack Zipes, De Beaumont intended Beauty and the Beast to teach self-sacrifice, modesty, virtue, and industriousness. Over time, many writers and creators have forgotten these intentions. Instead of focusing on building the romance itself, they have focused on the sensationalism of the romance. One writer that did get it right however, is British novelist and journalist Angela Carter. Known for feminist and magical realism, Carter published a short fiction collection The Bloody Chamber and other Adult Tales in 1979. This collection features not one, but two Beauty and the Beast retellings.

In writing these retellings, Carter intended to bring out the latent meanings of said fairy tale. By that logic, Beauty and the Beast is a story about a young woman finding her equal, and in doing so, has a sexual awakening. Through comparing De Beaumont’s variant with Carter’s two variants, The Courtship of Mr. Lyon and the Tiger’s Bride, we can understand the “true” meaning of Beauty and the Beast.

History

At its conception, Beauty and the Beast was first intended for adults and not young children. As stated in Formidable Fairy Tale: A Writer’s Guide, this particular story is a literary fairy tale. Literary fairy tales served as way for aristocratic men and women to take familiar stories and place their own ideas into it. For example, Beauty and the Beast has roots in the Cupid and Psyche myth, written by Apuleis in the second century AD. In that story, a young maiden named Psyche is whisked away into marriage by the god Cupid. Unable to a catch a glimpse of her new husband, Psyche worries she has married a monster. When she discovers his true identity, Cupid disappears on her. Psyche then risks everything to find him once again.

Literary fairy tales took myths, like that of Cupid and Psyche, and rearranged them to suit ideas of love, arranged marriage, and fidelity from the women’s perspective of that time period. Beauty and the Beast, then, is an updated version of the Cupid and Psyche myth for the seventeenth century. Jeanne-Marie Leprince De Beaumont used this particular fairy tale to teach young men and women how to achieve happiness. In her mind self-sacrifice, honesty, industriousness, and virtue in both sexes could lead to happy marriage no matter the circumstances.

Here in the twenty-first century, society’s perspective on love, arranged marriage, and fidelity has changed to a certain extent. Angela Carter acknowledges this, and puts her own ideas on those topics from a modern women’s perspective. She still uses common motifs associated with Beauty and the Beast. For example, the rose motif first used by De Beaumont is present in both retellings. The Courtship of Mr. Lyon, in particular, is heavily inspired by De Beaumont’s version.

The Courtship of Mr. Lyon

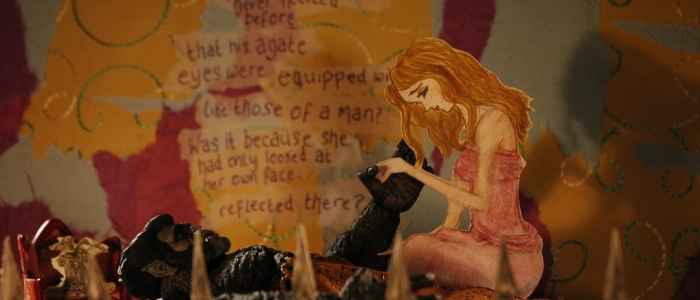

Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories features many fairy tales retold in a women-centered and sexually charged way. The Courtship of Mr. Lyon is but one of her Beauty and the Beast retellings. At the start, Beauty is consistently called “girl,” “child,” and “pet.” Her skin has the same “inner light” as the snow outside. Readers then have a very clear idea who Beauty is. She is childlike, innocent, and above all good. She is “untouched” by wickedness.

The rose motif, which occurs in nearly all retellings, represents Beauty as a character. A single white rose is all Beauty has requested from her father, something that is rare in the cold winter months. The Beast too covets white roses. When Beauty meets the Beast, a lion-esque figure, she considers him terrifying. At the same time, though, she considers him beautiful because lions are, in their own way, beautiful. She is “bewildered” by his otherness and it pressures her. Beauty refers to herself as a lamb in his presence.

The same purity and softness that accompanies Beauty is often attributed to the Beast, but in a different way. He first appears in the white light of the moon, a similar light that bathes Beauty in her introduction. His actions speak volumes about him. The Beast treats Beauty’s father kindly, until he tries to steal the Beast’s roses. Beauty’s father attempts to appease him by referring to him as “my lord,” but the Beast is not fooled. He fully acknowledges that he is a monster. The Beast invites Beauty and her father to come to dinner, where the Beast offers to help them with their money troubles. Beauty’s father is sent to London and the Beast suggests that Beauty stay with him in the meantime.

When the Beast converses with Beauty around his fireplace the light from the fire puts halo around his mane. From that visual clue, readers can infer that the Beast is not bad at all. They can picture him as a good companion for Beauty. Another sign comes from Beauty herself, who acknowledges they both must overcome their shyness. At the end of each conversation they have, the Beast falls to Beauty’s feet and kisses her hands before fleeing away from her.

As the “pressure” Beauty feels in the Beast’s presence begins to fade so too does her childishness. She begins to refer to herself as a house cat rather than a lamb. She is no longer called “girl” and her attachment to her father lessens until he phones her to come home. The Beast lets her go, but asks that she visit him some day. Despite Beauty’s feeling for him, she cannot make herself touch him, to give him a proper hug goodbye.

Back home she discovers she is not the same girl she was. She realizes that she is at the end of her adolescence and she can no longer hang back. Beauty returns to the Beast to discover him dying out of loneliness and starvation. She begs him to live and tells him if he’ll have her, she’ll never leave. Before Beauty’s eyes, the Beast transforms into a human man and she can still detect the lion in him. The two now called Mr. and Mrs. Lyon head to the garden and step on fallen rose petals.

Although not overtly sexual, The Courtship of Mr. Lyon is about a sexual awakening. The Beast is not the only one who undergoes a transformation, Beauty transforms from girl to woman. Readers know from the opening passage that Beauty is attached to her father and retains childlike innocence. When she arrives at the Beast’s home and he offers her a place to stay, Beauty reluctantly accepts and hates to see her father go. She feels dominated by him at first and fears him.

But as she spends time with the Beast and she acknowledges that she can see a reflection of herself in him, she gradually begins to give up that part of herself. Her inability to touch the Beast when her father comes calling, shows us the Beauty is not completely ready to give up her innocence. It’s only from the time she spent with Beast and her reflection on that time, that Beauty realizes she would not mind losing her innocence to the him. The fallen petals at the end of story show that Beauty has at last become woman and she found someone “rare” and worthy of her.

Carter’s variation of the tale focuses on Beauty owning her sexuality. Through discovering the Beast mirrors herself, Beauty is able to give herself to him. Much like women in the seventeenth century, modern women want equality in their relationships. Many women today and back then fear that they will enter abusive relationships; relationships where they have no power and are treated as objects and not human beings. Back when Beauty and the Beast was created, women could very easily get in this situation thanks to the popularity of arranged marriages. Carter still touches on the fear but in a modern setting.

Other popular Beauty and the Beast inspired tales, such as Twilight and 50 Shades of Grey, look at the sexual implications in the original story. Twilight and 50 Shades use the Beauty and the Beast archetypes as a way to explore sexuality. Those stories are essentially about a dominant male falling in love with a submissive female. These stories allow readers to experience the dominant/submissive lifestyle without having to physically experience it.

It’s the fact that he could hurt her but chooses not to (in most cases) that makes this archetype so popular. Therein lies the criticism many feminists have with the story. Why should Beauty be dominated by the Beast? Why can’t the power be shared between the two? In both Twilight and its carbon copy 50 Shades of Grey there is no equality. The beasts, Edward Cullen and Christian Grey, overstep their boundaries. They stalk their prospective lovers and consistently push them away.

In their minds they are doing the right thing by telling their lovers they are no good. However, despite this thinking they come back for more. They control all sexual aspects to the relationships as well. No matter how many times they tell their lovers they have the power, this so called power is never used. Bella Swan and Anastasia Steele are used and are under the illusion that they have found their soulmate. The danger between the coupling is what the authors are selling and not a healthy romance. Other writers, such as Angela Carter, remedy the power dynamic by turning Beauty into a Beast as well.

The Tiger’s Bride

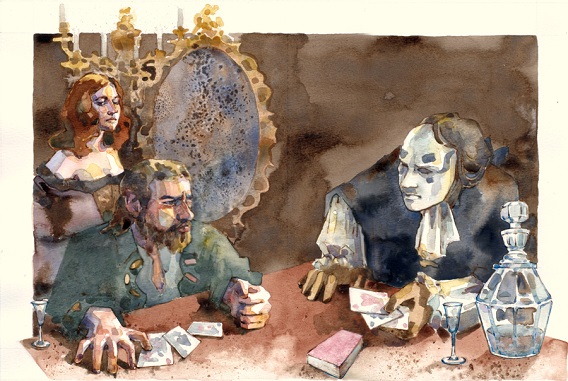

Angela Carter’s the Tiger’s Bride is narrated by Beauty herself, or what we as readers assume is Beauty. In this tale, Beauty is not the sweet innocent girl we know from other variants. She is tougher and wiser from growing up in the frigid North with her father. This Beauty is angry with her father for trading her away to a masked man after losing a game of cards. The masked man whom Beauty refers to as the Beast offers her a single white rose, for which she destroys immediately. It’s not her choice to become a prisoner of the Beast like in other versions.

Although the motifs of pure white snow and roses appear again in this variant, they are not used to the same effect. These innocent symbols are tainted instantly. For example, Beauty’s father asks for a rose so he knows that she forgives him. When she hands it to him her hand is cut by the thorns and she hands him a bloodstained rose, indicating there is blood lost between herself and her father.

On the way to the Beast’s home, Beauty remembers the tale of the tiger man and of a bear child born to a woman in town. She remembers squealing in disgust at these stories when she was young. She is under the impression that she is imprisoned by the real tiger man. Unlike Mr. Lyon, this Beast cannot speak and requires the aid of an inhuman valet. She realizes there are not any humans in her new home.

Soon the valet makes an unexpected request from his master to Beauty. He tells her the Beast wishes to see her unclothed and then will return her to her father. Beauty laughs at him outright and refuses. She tells him she will let him see an ankle and then must immediately be sent to a church to be cleansed. The Beast, unable to respond, cries a single tear. In this instance, Beauty is more beast like, more inhumane then the Beast. She treats him as something less than human.

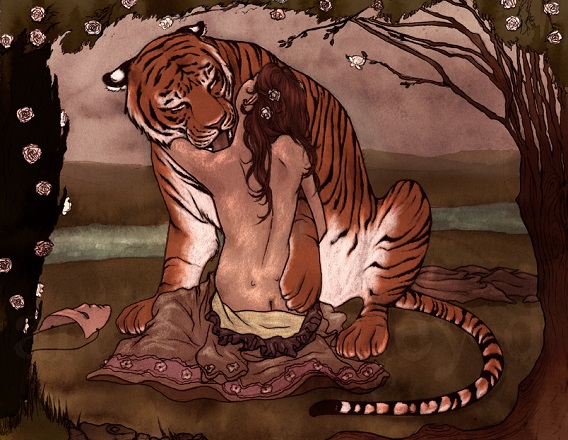

Beauty discovers that the Beast isn’t comfortable in his clothes. She suspects walking upright causes him pain and he tries to hide his natural scent with perfume. It seems to her that he is hiding something from her, as if he is afraid of rejection. Beauty begins to feel for him, but not enough to accept him. She continues to reject his request until he removes his own mask. When he does, she discovers he is in fact a tiger dressed in human clothing.

Beauty is surprised but not disgusted and finds him beautiful. She says to herself “a tiger will not lay down with lamb but the lamb could learn to run with tigers.” Beauty finally follows his request. The Beast in his natural state begins to lick off Beauty’s skin revealing tiger fur beneath her skin. In this tale, the Beast does not become a prince but Beauty becomes a Beast.

Unlike earlier variants, Beauty is not idealized to perfection. Typically, Beauty is treated as the perfect woman, someone who is kind, forgiving, and honest. Instead the Beast is a far more fragile character. He does not even act beastly. In fact, he is kind to her even when she laughs at his face. In most variants it is Beauty that changes the Beast, but in this case it is Beast that changes Beauty.

The Tiger’s Bride still focuses on building a relationship between equals. After all, it is only when the Beast reveals himself to her that Beauty is comfortable revealing herself. Beauty acknowledges that a tiger will not lay down with lamb, meaning she cannot be with the Beast unless she is a beast herself. When the Beast turns Beauty into a tiger, he is essentially cleansing her. She is giving up her life as human and presented a new life where she can start again. The only way this works is because these beastly qualities, that the Beast can relate to, are already in Beauty. It is their outer differences that keep them apart.

In this variant, Carter again touches on the women’s perspective on love and sexuality. Beauty is again in charge of herself and her body. Again through self-sacrifice and honesty Beauty and Beast are able to fall in love. Until they become equals they cannot be together. Beauty and the Beast works as a feminist romance because Beauty forms a partnership with the Beast. Both parties make sacrifices for one another and in doing so they understand what they mean to each other. These are the decisions that build a lasting and believable romance.

Twelve years after The Bloody Chamber and Other Adult Tales was published, Walt Disney Animation released their version of Beauty and the Beast. Like Angela Carter’s variants, this film too is a feminist love story. Belle, the Beauty, eschews the typical Disney tropes that her fellow Disney princess fall into. She is not dreaming of the day a prince will come to rescue her. Nor is she taken in by the first attractive guy she meets. Belle is independent, intelligent, and intensely loyal to her father. So much so she that is willing to sacrifice her dreams of adventure for his safety.

Twenty years later, Disney’s Beauty and the Beast remains the definitive version for many people. But if not for Carter’s variants beforehand, Belle would not have a model to based upon. The loyalty, self sacrifice, and honesty we see in Belle are also present in Carter’s variants. In this way the Courtship of Mr. Lyon and the Tiger’s Bride serve as a guideline for adapting this beloved romance. Hopefully, Disney will keep these elements in their live action remake set for 2017.

Work Cited

Carter, Angela. The Bloody Chamber and Other Adult Tales. New York, New York; Penguin Publishing Group. 1980. Print

Zipes, Jack. The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. Oxford, United Kingdom; Oxford University Press. 2000. Print.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Angela Carter is a brilliant writer. She is very aware of the stories. She is aware of the critics. I fins her writing brilliant but I find some of her female characters extremely difficult to either feel sympathy for or even see as an empowered character. Since she is a feminist, it is hard to fully connect with that as I am not, but I would assume she is attempting to prove that female characters are mobile and are not innocent. She does that well in most of the stories.

I’d heard a lot about Angela Carter, and read both of these stories. Thanks for the analysis.

For class I had to look at Tiger’s Bride from three different perspectives. A part of me thought the whole story was completely sexist, but I kept leaning toward the more magical tone of it. While there are definitely degrading moments in the book, when the narrator’s father wagered his daughter in a bet and lost, or when the beast demanded that she undress for him, I remember the end where she makes her own decision. So instead of Beauty changing the Beast it’s the opposite in this case.

Angela conveys her themes brilliantly; sexuality, gender stereotype, and misogyny.

I’ve read some of Angela Carter’s short stories before and liked them a lot. It has really been a great delight to read a whole compilation of them just recently. The mixture of the gothic and the mundane, the highly strung emotional and the almost uncouth works amazingly well.

She has a prose voice which is similar to that of modern authors such as Neil Gaiman or even perhaps Susanna Clarke and yet is remarkably her own.

Ms. Carter’s tales are fevered variations on nursery rhymes.

She is a writer who never shrinks from acknowledging the transformative power of sexual passion.

Thanks for the article. If nothing else, this gives many of us a reason to go back and read or re-read the original.

I need to look at the original tale, but, in the one that was read to me as a child, I thought that the lion turned into a handsome prince when she kissed him. Or, is that just Disney?

I’m guessing that Carter’s idea was that Beauty was losing beauty in the outside, more material world — “Her face was acquiring, instead of beauty, a lacquer of the invincible prettiness that characterises certain pampered, exquisite, expensive cats.”

I appreciate the article – shows a less commonly known history to a well-loved story, as well as presents a bit of an argument about the varying nature/interpretations that can be taken from various writings of the same tale. I as well have high hopes for the upcoming Disney remake.

Great article with some solid arguments, and well-written! I particularly enjoy your choice of pictures, they are gorgeous and compliment well your post.They capture the style and aesthetic of Carter’s work. Well done!

Agreed, the narrative is apropriate for the subject!

Carter wrote stories in a lope and growl that tugs my senses with familiarity.

Carter’s uses a decidedly feminist slant to re-tell familiar myths and stories.

Thank you!

I thought that Beauty did have a choice of whether or not to go back.

I think she was the one who chose to stay with the beast the first time; she wasn’t being held captive or forced. And definitely she was free not to return to him after their success in the city.

I recently read another story of hers called “Reflections” which also had a fairytale feeling but much darker in tone and much more compelling.

Thinking about the history of the author, there does seem to be a more feminist point of view than the original story.

Yes. Beauty makes her own decision to stay with him at first, and then she chooses to return to him.

Haha loved your description of 50 Shades and Twilight! Perfect comparisons.

I have always enjoyed fairytale retellings, and your analyses of these Beauty and the Beast retellings are well-written and presented beautifully.

This was lovely and the pictures you chose were beautiful.

I love the analysis provided. “Beauty and the Beast” is one of my favourite tales, and the Disney movie is one of my favourite films as well, and this article made me appreciate the tale more than I already did.

Wonderful!

Cagney makes some very valid points about the feminist aspects of the Beauty and the Beast motif. This motif also lends itself to an otherness critical analysis. Both Beauty and the Beast contain some faction of otherness, and it is the acceptance of each other’s otherness that blossoms into a romance. For example in the Disney version, Belle is a book nerd and the town clearly identifies her as “strange,” “peculiar,” rather odd very different from the rest of us,” and a girl who”doesn’t quite fit in” in the opening song of the movie. From the start Belle is identified by her otherness. Beast also is defined by his otherness as the townspeople refer to him as a monster. I am sure you get the picture. I have not read Angela Carter’s stories, but I suspect that you could find the same otherness in her versions. I would be interested in reading your take on this motif in her stories.

Carter’s fairy tale retellings are meant to be well known for being feminist, gothic, and original. For the most part, I didn’t feel that was true.

This site is very interesting in general. I’m bookmarking it.

I’m not sure if I’ve read work by this writer or not. Very likely I have but if so it’s not coming to mind.

Read carter’s literature. The story didn’t really captivated me.

I loved reading The Bloody Chamber and was so inspired I actually wrote my own Angela Carter-inspired fairy tale based on the Princess and the Pea. This was an interesting read to have Carter’s two Beauty and the Beast stories compared side-by-side!

Awesome connections that you draw between these different adaptations of this classic fairy tale. I would have enjoyed if you had touched a bit upon the theories of Claude Levi-Strauss and Vladimir Propp as well as the Aarne-Thompson classification systems that are used to identify recurring themes across fairy tales (and the tales themselves) between different cultures (Russian to German to Native American etc). It was awesome that you touched on the Apuleis origin; that contextual origin was super helpful in illuminating this subject.

I appreciate this article–for the references to a potential sexual awakening, as well as the theories of abuse and feminism. Well referenced, and well written.

This article was a surprising read for me. I had no idea there were so many retellings of The Beauty and the Beast. The summaries are nicely written, and the analysis is concise. I learned something, and became interested in a topic I wasn’t aware existed. Thank you for sharing the knowledge!

I thought the description of the man lurking inside the beast at the end was effective.

Carter’s writing style amazes me every single time…

I truly do not believe that the fairytale of, the Beauty and the Beast, is that much of a story who storyline is throughly and greatly “retold”. Taking in consideration the fact that the Beast is an animal with tangible human emotion in a house where teapots, candles, and clocks too portray human connections with the princess, I believe it is a good story but not much to detail the aesthetics.

I truly do not believe that the fairytale of, the Beauty and the Beast, is that much of a story who storyline is throughly and greatly “retold”. Taking in consideration the fact that the Beast is an animal with tangible human emotion in a house where teapots, candles, and clocks too portray human connections with the princess, I believe it is a good story but not much to detail the aesthetics.

Carter is a good writer, and much of a fan I am to the stories.

What?

Both of Angela’s work have rich story, and i enjoyed reading both.

Good comparisons between the different versions of each author on the same story!

It’s interesting to see how from an original story, all these versions reflect their author’s perspective towards growing up, sexual awakening, and feminism.

I find it quite interesting how these types of Faery Tales change over the years. Not only do many of them (the little mermaid, the ice queen, cinderella) become much lighter but keep similar plots, Beauty and the beast does not end up much lighter because it already starts with more of a mix of tones than most of the Disneyed stories.

Interesting read! Belle has always been one of my favorite Disney princesses but the older I got, the more I wondered if she was a victim of Stockholm Syndrome.

Beauty and the Beast is one of my favorite fairy tales, and I am pleasantly surprised to learn of these variants by Carter, as well as how Disney’s version is likely inspired by them. It had never occurred to me the tale had feminist themes in it, but thanks to your article, now I know, and I can see how Belle displays the traits of a strong, independent female character. I appreciate this happy enlightening, Cagney!

Great article. I really enjoyed the comparisons with 50 Shades and Twilight and the point you made about the modern reader’s reaction to the disparity between dominating male and submissive females.

I like that you mentioned a bit of context about the 17th century female power struggles in marriage settlements, although it would have been interesting if you offered an example of another literary text at the time that demonstrated similar ideas about marriage and power struggles to justify your point about growing female desire for equality in marriage, as I’m struggling to think of one at the top of my head.

Thank you for sharing, was very interesting!

Angela carter tries to give emphasis on the dehumanization of women in the society.

That man is already sub-human, and a woman must degrade herself to be with him. The story seems to say that the female form alone has the value of “a king’s ransom,” but that in every sexual encounter she must descend into the bestial to match the base sexual ferocity of man.

I had never heard of Angela Carter before. Now I definitely want to read some of her work!

Great article! I have never read Angela Carter’s adaptations, but you describe her work beautifully! Well done!

I have always been fascinated with Beauty & The Beast, and the many layers of love, growth, and inner strength associated with it. These retellings not only furthered my love for this story, but successfully enhanced my knowledge of all of the different ways to view the story. I have always felt that this story allowed the traditional roles of love and sex to be switched. The “Beast” is automatically assumed to be the strong provider, but in the way I view the story the Beauty was the one who gave him the strength; basically supplying the him with the things he lacked. Great job on this post

Is there a reason why the research is so thin with this piece? Zipes is good but he’s not the only bloke out there writing about FTs.

I just realized that I haven’t read these yet! I need to do that before I go back to work tomorrow.

Wonderful analysis of Angela Carter! I am intrigued and now must read these stories!

Wonderful analysis of Angela Carter! I am intrigued! I think you are a wonderful writer with a marvelous ability to connect with your readers and get your point across without overstatements. Great work!

In the past, I’ve heard people discuss different sides of “Beauty and the Beast” — whether it’s a story with a more feminist plot line than some or if it’s revealing an abusive story in the form of a fairytale. I really appreciate the way you discuss different versions of this story and how it can be a feminist story, depending on how beauty and the beast and their relationships are characterized (e.g. if they are equals with only “their outer differences that keep them apart”). I have not read either of those stories by Angela Carter, but I’m curious to find and read them now!

This is a very engaging article. I am disappointed, however, that the focus of so many modern retellings of Beauty and the Beast is on sexual domination and submission. Isn’t it interesting how, among all the themes that could be gleaned from the story, that is the one that modern writers run with? Unfortunately, this is just another example of the obsession our culture has with sex.

I always found the real wonder and joy in Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont’s Beauty and the Beast to be the fact that, despite the Beast’s terrible ugliness, Beauty found that she loved him. She pitied him. She wasn’t really hoping for anything for herself out of their relationship.

But perhaps this is simply how I chose to read into the story, and am reading into it incorrectly. Either way, themes besides sexual awakening could be explored here.

Womankind seems to have much greater rein on her own sexuality than man; perhaps this is why he tries to desperately to control her. The male desire is a burden of lust that a woman, once seduced, condescends to satisfy. Thus pity, or some form of it, is always present in sex, some empathy for his helpless hunger. Woman lets herself be conquered, and transformed, without the complete knowledge of her own magnetism.

I don’t think that The Tiger’s Bride is focused on sex that much, in terms of domination and submission. Rather, I think it’s more focused on the narrative of “love’s true form.” Moreover, traditional fairy tales are focused on sex themselves, but not as blatantly as contemporary narratives. The various versions of Little Red Riding Hood, for example, are cautionary tales for young women to not interact with men so as not to compromise virginity. It’s been difficult for me to read Beaumont’s version with not only a feminist lens (can’t help it, that’s who I am) and a contemporary lens. Beauty’s character and interaction with others seems very contrived. Moreover, her virtues are only illuminated because they contrast her sisters’ so much. I found that her return to The Beast is one of pity, like you said. However, I read her love for him as her “settling” for him after seeing her sisters’ husbands’ horrible nature.

I can’t wait to read this version. Maybe someday Disney will tell the tale according to its original.

I think this article was really well written. It explored various retellings of Beauty and the Beast that are apt in her analysis. She is able to discuss the various facets of her argument well and is able to illuminate further exploration on a topic not much discussed.

I really love fairytales and how we see them played out time and time again in other stories.

I really enjoy. The article’s subject is amusing. I like analyze of The Beauty and the Beast as a feminist fable and I believe that it is a feminist fable. the idea of this fable as an archetype for Twilight and 50 Shades of Grey is wonderful. choice of pictures is great.

A greatly enjoyable read. I had no previous knowledge about these fairy tales and their variants. The concept of the feminist princess/lead female character, especially in early 17th-century literature, is not commonly discussed or accredited; in this setting, it is especially important when faced with a dominant/submissive relationship to establish the ability and reason within the male counterpart to not take advantage of the female, despite the ever-popular progression that involves the man projecting on to the woman his desires, regardless of her level of comfort. What I’m trying to say (in a long-winded fashion, no less) is that these types of analyses are necessary for us in modern-day society. To understand the stories we love today and the progression of them, we must look back into the past from when they originated. Thoroughly enjoyable article. Keep up the great work and the interesting article topics!

I never actually looked at these stories from a feminist or non feminist point of view before. This was very enlightening and well written. I really liked the adaptations of the story you chose to write about.

I was recently introduced to Angela Carter, and love what I’ve seen of her work so far. I liked your symbolic analysis, but really appreciated getting the history of the story of “Beauty and the Beast”, and seeing Carter’s interpretation compared with the original and other well-known retellings. I never knew the original was written (or popularized, rather) by a woman! Great lesson in literary history. Thanks!

What an interesting and informative article. I had no idea that there this many retelling of Beauty and the Beast.

It is a beautiful story and I liked your article because you focused on the variations of the theme. Of late, feminists have criticized it for the women’s role the potential to read abusive overtones.

Your article does the story justice and defends the theme of the transformative power of love and the awakening of a young woman in a nice way. I look forward to reading more from you.

Like Munjeera, I had no idea there were so many versions of Beauty and the Beast. I really like that you wrote about this because most of the time there is a clash between people loving Disney princesses and hating them. You did a great job in not only teaching us the history of Beauty and the Beast, but defending Belle’s character. She is a great one and one of my favorites in the Disney world.

I hope the live action will do the story and Belle justice. I’m sure it will, considering Emma Watson is a force to be reckoned with.

A whole and solid piece. I loved that you consulted secondary sources; they fortify your argument elegantly. I think you could have been more concise, perhaps by choosing a single focal point. However, as others have said, you offer an informative and interesting article. It was lovely to see different versions of Beauty and the Beast contrasted and compared to each other.

Great read. I love Angela Carter, and I thought that you explored both stories quite well. I particularly enjoyed your take on white snow and roses, two recurring symbols throughout her collection.

It was nice to see someone here, McGaggers, i well leave that alone–give a bit of credit to Apuleius and his books, which like statius and other italic books gave the fairy tale a lot of what the Grimm’s took out and which w as

stomped dead by uncle Walt and others. There is a corresponding Metamorphosis to this, in Ovid, Clinton would know, of a beauty and beast type story, i cant recall which one it is, refined in the famous essay by Calvino, but dont have that book anymore…was it Hermaphroditus, some monster falls for a woman or she fur him, but it beieng from the Romans, is much more sexual and adult and cosmopolitan than any nuns of feminists would like.

A return to the primal and thus intrinsically equal nature of both sexes. Lovely read.

The Beast has shades of Enkidu in Epic of Gilgamesh.

An excellent article, well written and fully attuned to the nuances presented by this timeless tale. Angela Carter is amongst my favourite authors, and for all the reasons presented here.