Neil Gaiman and Stephen King: The Power of Realism in Postmodern Fantasy

What would fiction be without at least a little fantasy? The world of storytelling is a diverse one that ranges from emotionally complex tales of tragedy, to carefully paced political satire, to gripping and immersive whodunnits with pointy-moustached detectives. But it is the fantasy novel in particular that has always captured a unique part of the imagination. Dwarves, dragons and djinn, heroes, hobbits and hags, goblins, ghosts and gods. It’s escapism at its best – entirely different worlds, with entirely different rules. Treasure troves of stories, full of beauty, epic adventure, and best of all, magic. The power of the impossible, the power to bend the elements to your will, the power to do what cannot be done.

Yet perhaps there is more to magic, more to fantasy, than simply escapism. Realistic elements to the genre are nothing new – Bilbo Baggins smoked a pipe and Thorin had his own racial prejudices in The Hobbit. The world of Harry Potter was a magical mirror of our own. In addition, complex politics have emerged as key devices in works such as Robin Hobb’s Farseer novels, Jonathan Stroud’s Bartimaeus sequence and of course George R.R Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series.

Despite these elements of realism, however, all these stories are firmly set apart from the real world – our world – in terms of setting and internal logic. The other side of the coin – the side that sticks closer to reality and adds a layer of the fantastic to stir things up – is magical realism, an intriguing category of literature that is often difficult to define because of the complexities surrounding it. The power of this sub-genre is its ability to achieve, in many ways, the exact opposite of fantasy’s escapism, by creating stories with both a degree of the entrancing, otherworldly qualities that make fantasy so fascinating, and a sharp edge of reality that can unsettle and provoke the reader in a unique and distinctly special way. And in the world of postmodern, contemporary literature, there are few writers who seem to be able to utilise this form as well as Neil Gaiman and Stephen King.

Long Nights, Dark Days: The Horror of Reality

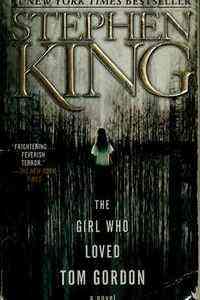

Stephen King’s novella The Girl who Loved Tom Gordon is often overlooked as a great story in favour of more popular tales, and perhaps rightfully so. To those who have read King’s best works, it may seem comparatively ordinary and overly simple. Nonetheless, it is a great story – the journey of Trisha McFarland, a nine-year-old lost in the woods, is written with conviction and subtle observation, King’s insight into the mind of a child every bit as compelling as his narrative for Paul Sheldon in Misery. It’s described as psychological horror, but there are arguably elements of magical realism also present. The woods themselves are presented as sinister and almost intelligent, luring Trisha further from civilisation towards the God of the Lost, a creature she begins to believe is stalking her, waiting for her to inevitably lose her incredible willpower.

While this supernatural aspect of the novella certainly adds a level of suspense and tension, the true horror of the tale comes from the less fantastical ideas – ideas that are striking in their simplicity, and brutal in their realistic nature. The greatest threats to Trisha are not the nightmare beasts that lurk in the dark, but instead hunger, thirst, exhaustion, insects, fever and loneliness (and it is here that the psychological horror really kicks in), all described in grotesque, wince-inducing detail by King.

This lends the story a terrifyingly plausible edge, the character of Trisha responding to such challenges in a way that is at once devastatingly relatable and compellingly heroic – and because of this, every failure, every triumph, every stage of her journey has a powerful, unique impact on the reader. The genius of King’s writing here comes not from his ability to imagine complex kingdoms or repulsive creatures (although the latter certainly helps in places), but from his understanding of the very real terror of isolation and his character study of McFarland, a nine-year-old of wonderfully believable, wonderfully indomitable human spirit.

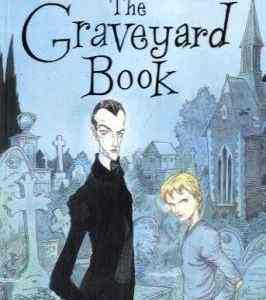

Neil Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book is in many ways a different beast altogether: a gothic fantasy chronicling the childhood of Nobody Owens (or “Bod”), a boy raised by ghosts following the murder of his family. This novel fits the fantasy category somewhat more appropriately – internal logic and laws, magic, ghosts and demons all play large roles in the book, as well as an age-old conflict between two powerful forces.

Yet Gaiman chooses to set the story – for the most part – firmly within our world. This is an intriguing decision that arguably pushes the work again into the realm of magical realism, or at least something resembling it. When reading the novel, the benefits of this choice are almost immediately apparent. The opening chapter introduces us to the villainous Jack, searching for the young Bod whilst clutching a knife. Gaiman’s elegant prose serves only to add to the unease, his allusions to Jack’s acts of murder sinister and gripping in equal measure. Once again, realism is used as a tool to increase horror as Gaiman describes the interior of the familiar, modern house where this has taken place – close to home in the frightening, disturbing sense.

The tales of The Graveyard Book range from character pieces, such as Bod’s first meeting with deceased witch Liza Hempstock, to high-end adventure in the graveyard and beyond. With a large cast of highly unusual characters and ideas including a secret ghoul-gate to a horrifying demonic underworld, a strange, whispering being that resides under a crypt, a Hound of God that works part-time as a nanny and, of course, the mysterious entity that is Bod’s guardian Silas, it’s often easy to class the novel as pure fantasy.

However, it could be argued that Gaiman never quite crosses this line entirely, instead repeatedly blending these elements with reality to produce a work that, by the time the last page is turned, is a satisfyingly dark coming-of-age story. The constant presence of the real world makes it especially potent, particularly for the character of Bod. The world from which he comes is by turns fascinating and appalling to him as he witnesses both the good and the bad of humanity. It is the recurring comparison and contrast of this – of us – with the world of the dead that makes him a unique, meaningful and memorable character. This is magical realism at it’s best: terrifying, captivating, entertaining and provocative.

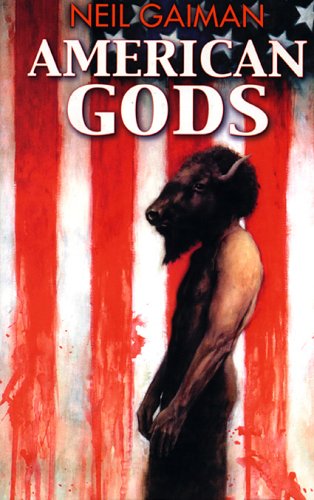

American Gods and The Gunslinger: The Epics

Gaiman’s American Gods and King’s The Gunslinger are two further examples of reality and fantasy colliding, and as with the aforementioned works, they are at once strikingly similar and enormously different. Both stories include the heavy use of symbolism, both focus on the concept of a journey (though it could be argued this particular point could be applied to all fiction) and both use troubled protagonists as a means of exploring a flawed world full of relics long forgotten. The primary difference is as simple as this: where American Gods is a novel set in real, modern America with an edge of fantasy to it, The Gunslinger takes place in a fantastical land with an edge of America to it. Perhaps this is stretching the definition of magical realism a bit, but it’s hard to dispute that both novels use their strong ties to reality to sharpen their edges and increase their power.

American Gods could be summarised as the literary equivalent of a road movie, with added Gods, subplots and magic. The story of ex-convict Shadow Moon and his journey across a turbulent America where forgotten Gods secretly war with new deities, the primary thread follows him and the mysterious con artist Mr Wednesday as they explore this bizarre hidden world, all the while encountering new beings and seeking to avoid the organisation that hunts them. The fantastical plays a large part here – before the reader is even halfway through the novel, Shadow has encountered an ancient spider god, a being that feeds on people’s obsession with the media, a series of dark and mystical dreams, and so much more. As with The Graveyard Book, however, Gaiman’s talent here lies in blending fantasy with reality. In this case, he even blurs the line between the two, to the point where the magical elements seems harsh, dark and real and the real elements eerily magical and supernatural.

American Gods is, as anyone who has read it may tell you, a work of fiction that gets under the skin in a strange, unsettling manner. This is largely a result of Gaiman’s immense imagination combining with an observant look at the world around us to create distinct discomfort. This feeling is greatly enhanced by the novel’s ‘Coming to America’ sections – short interludes that deviate from the main storyline, telling tales of various characters from the past and the present, all tied by the common theme of worship and identity. These interruptions to the main story serve to add greater depth to Gaiman’s depiction of America, building on this strange world that is neither fantasy nor reality and searching deeper into the heart of ours in the process. The effect is as disturbing as it is captivating, and it is Gaiman’s talent for achieving this hypnotic yet unnerving reflection of ourselves that makes American Gods a disturbing and unforgettable read.

The Gunslinger, the first instalment in Stephen King’s The Dark Tower sequence, introduces the reader to a strange, broken world that – as the blurb puts it – ‘frighteningly echoes our own’. An adequate description – within the first few chapters of the book, it’s easy to assume that we are looking at tale of our own world following some kind of apocalypse. A vast, unforgiving desert where the world has ‘moved on’. Small towns where pianists play empty and soulless covers of ‘Hey Jude’. Hunger, thirst, desperation. It’s immediately apparent that the world of The Dark Tower is no traditional fantasy setting. Yet as we learn more of the mysterious man in black, and of the gunslinger’s own past, we begin to understand that the rules of this world are far from ordinary or logical. Magic exists only in the dark variety, in the form of curses, charms, prophecies and hungry, ensnaring traps laid for unwitting victims. King bridges the gap between these fantastical elements and the aforementioned areas of realism by making The Gunslinger essentially a western: a genre that falls almost perfectly between gritty authentic tale and legendary myth.

So what about the realism? Why does King choose to consistently link the world back to our own, through religious and cultural references and through the character of misplaced New-Yorker Jake? Perhaps it is for the same reason as Gaiman in American Gods – to hold a warped mirror to the face of the reader, resulting in an unpleasant sensation of familiarity that creates compelling contrast with the fantastical. One thing is for sure: although the conclusion of this first chapter is at once thrilling and oddly unsatisfying, as can be expected of the beginning of such a series, what the reader is really left with is a surreal sense of understanding.

The novel is not much longer than 200 pages – strikingly short considering the typical length of a fantasy book. Yet, similarly again to American Gods, it feels as though a journey has taken place that has changed our knowledge of this setting. It seems to make a bizarre kind of sense to us as inhabitants of our own odd world, and as such we fully accept it and the story. As with all good fantasy works, we are motivated to continue the journey through the connections we feel with the world and the characters. In this particular instance, however, it is the moments of bitter reality that, ironically, lend the story its magic.

A Credit to the Culture: The value of Gaiman and King

Both King and Gaiman are adept character writers with great talent in creating fully fleshed out and believable individuals with minds as complex as any real human being. Their imaginations allow them to range greatly in the scope and surreality of their writing and creations, distinguishing them as unique, inventive and terrifyingly observant authors in the modern world of literature.

Their works can be seen to demonstrate a special understanding of magical realism and its potential for creating a particularly powerful, poetic, frightening and above all lingering portrait of today’s world whilst still telling a wonderful, captivating story. Escapism? To an extent, yes, but then all fiction qualifies as escapism. It is this ability to capture the essence of our world in their writing, however, that sets them apart. They are pioneers of the postmodern, creating work that is original and imaginative but also uniquely personal and introspective to every reader. It is this that cements them as invaluable assets to a special kind of magical realism – the kind that gets under the skin and stays there.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

King scares the crap out of me, but Gaiman just creeps me out.

Thanks for reading! And yeah, I can understand that. In many cases King also seems to favour the use of vivid, violent imagery – a particular moment in The Green Mile stands out – whereas Gaiman is lighter and perhaps less brutally shocking, but at the same time very unsettling.

Whatever similarities two authors may have, they are both well-established in their own right.

Oh, definitely. One of the things I find so interesting is the range of their writing. Although this article looks mainly at a particular category, both authors are more than capable of exploring other areas. I’m currently reading King’s crime thriller Mr Mercedes, which I’m starting to think may be one of his best, and after reading the first volume of The Sandman, I’m convinced that Gaiman is every bit as adept with comics as he is with novels. Thanks for the read and the comment!

Really smartly chosen subject matter and great use of pictures. I found this very entertaining. Good work

Thanks so much for reading and commenting (and editing)! Glad you like the way it’s turned out.

Great article and your examples of why Neil Gaiman and Stephen King are the best fantasy living writers is spot-on. For men, My favorite Stephen King book is The Shining, and my favorite of Neil Gaiman work is the Sandman books.

Thanks for reading, and for being so helpful in the editing process! I have yet to read The Shining (maybe a little strange considering how much I enjoy King’s work), but it’s definitely on my list for the future. And yeah, what I’ve read of The Sandman is wonderful stuff, Gaiman at his best.

They write two completely different genres for the most part, and I often find King’s work to be lengthy and unnecessary.

I love Gaiman’s YA stuff–Coraline, the Graveyard Book, and Stardust are all exemplary in my opinion.

I have to confess, I may be the only person on the planet who’s never read Gaiman. I plan to rectify the situation immediately!

No, you’re not. And no, you won’t.

I’m a sucker for both!

Neil Gaiman’s tragedy is that his strongest work, by far, is way behind him (Sandman). I think his writing style is served better by the graphic novel format.

I think both writers have fantastic short stories.

I have a love affair with all things even slightly mythology based.

Anyone who’s not a fan of King and Gaiman are really missing out.

For an introduction Stephen King you really can’t go wrong with Carrie, The Shining, Pet Sematary, or The Dark Half. I haven’t picked it up yet but his Dark Tower series is supposed to be amazing.

For Neil Gaiman I’d recommend American Gods (and Anansi Boys afterwards), Neverwhere is good, Stardust, and Good Omens (which he co-wrote with Terry Pratchett and is a hilarious take on the Biblical apocolypse).

In three weeks you can read all of Gaiman’s books so no need to look for the best ones, I recommend the graphical novel series Sandman (may be a bit difficult/expensive to get the full series), then American Gods. My favorite Stephen King book is IT (actually only book I had with me when I found myself stuck in the hospital for a week without any visitors to bring more books), but I also liked Duma Key.

My favorite Stephen King book is Misery.

Thank you Neil Gaiman and Stephen King for everything.

These people are brilliant.

I am one of the only people in the world who can’t stand Neil Gaiman’s stuff. I believe the reason is because all his protagonists I’ve encountered are the same mundane guy, sans personality. Whereas Stephen King’s strength is the depth he gives his stories, usually with his characters.

Thanks for reading! Interesting comment. I can see where you’re coming from with your stance on Gaiman’s protagonists – I guess I’m largely more interested in his supporting characters (Death in The Sandman, Mr Wednesday in American Gods, etc.). Absolutely agree on your analysis of King’s skill. He seems to have a unique and immensely observant understanding of human beings that give his characters such depth.

Whenever I read King I always feels like H.P. Lovecraft is nagging me.

While Gaiman’s most popular books are American Gods and Good Omens, I enjoyed Neverwhere and Stardust a lot more.

My favourite is Neverwhere.

I will actually read American gods now. Been on the shelf for 5 years too long.

It is a stunning book, you should read it immediately.

It’s WONDERFUL. Enjoy. (If you’re into it, the audible version is terrific, too – terrfic reading.)

I only recently began reading works done by Stephen King at the recommendation of my father. I did read Carrie when I was younger and it was not the most enjoyable experience, but I recently read it again and enjoyed it. Perhaps it simply terrified me as a young girl. I really enjoyed most of King’s works that I have read, except Under the Dome was too drawn out.

I have not read a single work by Gaiman though. I feel like, after reading this article, I should take a look at some.

Yeah, I only recently became interested in King (don’t think I could have handled it when I was younger!). I think it was The Green Mile that got me really hooked, and I have yet to read a lot of his horror (though I fully intend to read The Shining and Carrie at some point). Gaiman is a really interesting writer – I still think The Graveyard Book is one of the most enjoyable books I’ve ever read.

Thanks for reading and commenting!

Whatever aspects of his work make it stand out, Neil Gaiman is just a gifted author. I think that the one thing that saved McKean’s “Mirrormask” from being a total commercial failure was the fact that Gaiman wrote the screenplay. Also, I know it’s not the best book ever, but I really feel that his Coraline was and is underrated. Part of that may be thanks to the awful movie of it, though. Anyways, everybody here should try to get the audio recording of it from the library. Gaiman reads it himself, and the experience is in a class of its own. You should listen to his reading of the Graveyard Book too, come to that.

Thanks for the read and the comment!

And yeah, definitely agree on the matter of Gaiman’s talent. He’s great at pretty much anything he writes. I’ll have to read Coraline at some point, it certainly seems intriguing.

I’ve never read any of King or Gaiman, in all honesty, but this post definitely increases my respect for both of them. There’s a lot to be learned, it appears, from these two authors!

Yeah, I’d say so, at least. They definitely seem to have unique and interesting outlooks on the world.

Thanks for reading and commenting, much appreciated!

I think I had Gaiman confused with some other author because hearing about these books is throwing me for a loop. American Gods sounds fantastic, that kind of grotesque setting / or rather, focus on how dark and morbid the world is reminds me a lot of several of Shakespeare’s plays. Othello, Hamlet and Richard III are good examples: the small references or things that create a sense of the world around the characters are cynical, dark, and evil.

It adds a really interesting light to some of the scenes and characters. How has the world corrupted them?

Yeah, darkness is certainly a prevalent theme in Gaiman’s work. Interesting comparison – there’s other evidence to support that idea, too. In American Gods, for instance, there’s something of a focus on trickery, deception and cons, potentially providing similarities with Iago’s actions in Othello.

Thanks for taking the time to read and comment!

I like your point that fantasy can highlight real-world concerns like hunger and sickness–that these concerns seem especially dire when they are juxtaposed with fantastic nightmare creatures and are revealed to be more distressing.

I’d be interested to know your thoughts about Gaiman’s Neverwhere. From my understanding the BBC commissioned a work about the homeless, resulting in the Neverwhere screenplay. Gaiman’s descriptions of London Below are incredibly realistic, gritty, and dark but in many ways the magical world seems uncomfortably close to a romanticization of homeless life.

Very intriguing article, though a little eerie as I have three of the books mentioned above sitting beside me as I read this. I had never thought to use the term “magical realism” for either author before.

Part of me wonders, though, how using Stardust as a comparison would have changed the article, or at least what points you may have pulled from it.

Stardust is probably my favorite Neil Gaiman novel. I definitely agree with you that the use of Stardust in this article would be quite an interesting read.

Whilst I will admit that the best novels don’t necessarily fall into a genre, I would say that the examples you have chosen are very much fantasy rather than magic-realism. Magic realism is very much realism, with hints of the unexplanable. Examples such as Wise CHildren, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and The Aleph (the Borges short story) are good examples where the extreme bits in the novel seem almost believable and could be explained away as science or an unreliable narrator – but the writer decides to make it magical instead. Your article is intriguing though, in that the placing of fantasy so close to reality does make it more tangible.

Come to think of it, King’s the Green Mile would have been a better example as well…

Yeah, the actual definition/classification was something I was a little unsure of when writing this. I suppose I used the term to distinguish between full-on ‘traditional’ fantasy and the kind of work King and Gaiman produce. The thing about magical realism is that it’s so hard to pin down to an exact meaning – that said, the criteria you’ve put across here is really well thought out, and when looking at it that way, you’re absolutely right. The specified works are a little out of place (though I may argue the case of The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon).

The Green Mile might just be my favourite King novel, and is without question a great example of magical realism. I didn’t use it here because, as you say, I was focusing on more fantasy heavy stories. But yeah, it may have been more appropriate.

Thanks for taking the time to read and comment, much appreciated!

I think definately these are types of modern fiction that fall outside traditional genres. Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant is a great example of a ‘controversial’ book simply because people didn’t know what genre it was! Lots of the stuff you mentioned can fall into that catergory too.

Fantasy is fun and brings you back you used your imagination almost 100% of the time as a child. It is the unknown and placing the feeling in a modern realistic setting is where magic happens. For example in ABCs tv show Once Upon a Time, most of the show is set in a small town in Maine but it is untouched and unknown to the outside world. At first there is no seen magic but it is buried deep within the town and people. Just thinking that Snow White, the evil queen and rumpelstiltskin are having adventures in a US state makes you want to get on a plane.

You captured two dark storytellers very well. I’m not as versed in Neil Gaiman as I’d like to be, but I read a lot of Stephen King growing up, and I have to agree that his narratives are pioneering horror and magical realism in the postmodern.

What always struck me about King was the way he often made inter-human conflict the driving force. In Under the Dome, the trapped citizens face more conflict from the power-struggle than the dome itself. Often, King’s magical element is only a catalyst for human conflict. Pet Sematary and Needful Things are good examples of this. In Carrie, the human conflict creates the magical element, which is then fueled by further human conflict. The villains aren’t necessarily the magical elements, but the humans who use them.

My point is: King’s magical realism seems to be lens for looking into society. He can explain our conflict-driven world through his magical world. When reading his characters, we see ourselves. We are not heroes, or knights, or wizards, but we are writers, and cops, and doctors, and parents, and sometimes the world feels utterly against us. It’s why I love Stephen King horror. The enemy is not someone with an evil nature–it’s us.

I love both Stephen King and Neil Gaiman. Neil Gaiman is who I strive to be as a writer.

I feel that it is important to realize that the Post-Modern era is considered, by many scholars, to have ended approximately in the year 2000. Furthermore, Post-Modern era novels are characterized by radical changes to form and narration. Neil Gaiman’s fantasies, while spanning around the end of the Post-Modern era and the beginning of the new era of literature, tend to be less stream-of-consciousness and more first-person narrator. I would argue that the fantasy literature of Neil Gaiman and Stephen King are typical of a new style of writing and literature for the 21st century.

Ah, that’s interesting. I hadn’t quite thought of it like that. I guess a more appropriate classification would have been ‘contemporary’. Their respective styles are definitely something new.

Thanks for reading and commenting!

I’m close to reading everything Neil Gaiman ever wrote, but I still haven’t gotten around to reading anything by Stephen King (which is a crying shame since I own the first book in the Dark Tower series). I would definitely agree that Gaiman is one of the most influential forces in contemporary literature right now, and I’m in the middle of some research on authors like him and Lev Grossman. However, I’m a little confused by your juxtaposition of fantasy and realism. I would say that the genre of fantasy isn’t naturally opposed to realism, because of fairy tales, magical events treated in an everyday, matter-of-fact, real world way. It just doesn’t feel like that to us now, because we’re far enough removed from the stories that kings and peasants and cottages feel just as ‘fantastical’ to us as fairies and witches. The genre of magical realism may be a relatively modern development, but there’s always been a place for realism under the broad umbrella of fantasy.

Yeah, that’s an excellent point. I guess I was referring to the fantasy of writers such as Tolkien and Martin – while there are definite undertones of very real elements in their work, in today’s society the settings are often seen as fairly removed.

But of course, as you say, it all has its roots in fairy tales, taking content from basic primitive hopes and fears, with scenarios fairly close to home. Definitely worth thinking about.

Thanks for reading and commenting!

You got this so spot on. First of all, I don’t think you could have picked two better examples for this. And yes, these stories know how to stay with you. The characters are believable yet twisted and, therefore, memorable. The settings make us feel eerily connected. And the plots almost don’t even matter. I become so consumed with the characters and setting that it didn’t even matter that I had no idea where the plots were going. The fact that the plots were just as eerily amazing was just icing on the cake.

Yeah, ‘consumed’ is a great word to use. There’s just something so immersive about the writing, particularly in stuff like American Gods.

Thanks for the read and the comment!

Excellent article about two excellent authors. The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon was actually the first King novel I read, and it was unflinching in its portrayal of a girl trying to survive in nature. Definitely left an impact on me as somebody who was around the same age as the protagonist. The aspects of realism in Gaiman’s Neverwhere and American Gods really gave the stories an emotional resonance. George RR Martin has the same impact as well in the realm of dark fantasy. Awesome work.

While I haven’t read all the books that are referred to in this post (including TGWLTG – though after reading the article, I’ll probably check it out), to me the biggest masterpiece of those that are mentioned here is Jonathan Stroud’s Bartimaeus series – just wanted to jump on the opportunity, as those books aren’t mentioned nearly enough in talks of quality fantasy.

not to harp on a previous comment, just forming an opinion, however,I feel as though Neil’s novels are magic realism. The Ocean at the end of the lane, for example contains the underlying message of there being things that we believe as children that adults tend to forget. the novel is rooted in realism but the realistic aspect of the novel is whats been conformed to the boy by his parents. only when the narrator is taken under Letti’s way of seeing the world does he find the magic under the surface.