What is the Purpose of Dystopian Literature?

A dystopia is an unpleasant state – to put it more simply ‘not-good place’ is the translation from ancient Greek, the polar opposite of a utopia. The traditional interpretation of dystopian literature is that it is a bleak warning to its readers of the dangers of totalitarianism. Of course, such political ideas did drive authors such as George Orwell who was inspired after experiencing the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War first hand. However, there is so much more to the genre than the purpose of acting as a warning of certain political ideologies, although this does still remain a fundamental part of many of dystopian novels. The endurance of dystopian classics such as Huxley’s Brave New World, and Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984, along with the genre’s growing popularity in young-adult fiction suggests there is something beyond the warning feature of a dystopian novel.

Philosophical questions

In a less religious society, it is interesting to interpret dystopian fiction as a twisted source of morality. In most dystopian novels, one is presented with aspects of brutality, or at least what we consider immoral. Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange for example, contains aspects of “ultra-violence” and rape and was so shocking that the film version, directed by Stanley Kubrick was actually withdrawn from the UK by Kubrick himself in 1973, following debates in Parliament regarding the film’s nature and religious protests. However, beyond the brutality, one is presented with the “philosophical novel” as Time describes it, which questions what exactly makes a person good. Stanley Kubrick eloquently stated that “The essential moral question is whether or not a man can be good without having the option to be evil and whether such a creature is still human.” This is seen when the main character, Alex, begins as a man of savagery, with his reasoning being “What I do I do because I like to do” which raises questions not only on free will, but what is natural. Is it simply that he has been born in such a way that he enjoys violence? Or, is it a statement acknowledging that he has the choice to act in any way he wishes? Finally, Alex is arrested, and eventually he is given correctional therapy in which he then becomes ill anytime he even thinks about violence. This highlights Kubrick’s essential moral question – if we are forced to be good, does that necessarily make us good?

A lesser question that lies in the background of both the film and novel of A Clockwork Orange is within its music. What makes Alex different from his friends is his enjoyment of classical music such as Beethoven, Bach and Mozart. There are a number of occasions both in the film and novel whereby Alex beats or rapes someone to such music. Author, Blake Morrison says how “Burgess uses music to address the question of whether high art is civilising.” This very idea Burgess openly recognises when Alex says how he read an article about “how Modern Youth would be better off if A Lively Appreciation Of The Arts could be like encouraged”, however it is clear this is certainly not the case. Therefore, Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange addresses moral questions and doubts about how society may perceive music by using a dystopian background in which violence is more common.

Philip K. Dick raises other philosophical questions in his novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (the basis for the film, Blade Runner). In this futuristic science-fiction novel, Rick Deckard, a bounty hunter is ordered to “retire” (kill) six Nexus-6 model androids who have escaped. During this pursuit, there is an evident exploration of what it is to be human, such as what traits define us as human? Empathy, in particular, is one aspect that is considered. For example, one can assume androids have no empathy. Deckard originally recognises this, saying “An android doesn’t care what happens to another android. That’s one of the indications we look for.” However, there is an irony to his words, for example, when Rachael (an android) displays hints of empathy for other androids in actions whereby she seduces Deckard in an attempt to prevent him from killing them. Philip K. Dick’s novel is one that questions what it is to be human since empathy can not always be associated with it since Deckard is living in a world in which some androids have more empathy than humans themselves. Science-fiction is a brilliant gateway into such ideas since the author can create a world in which our own ideas are tested through the prism of such advanced technology.

Atwood’s speculative fiction

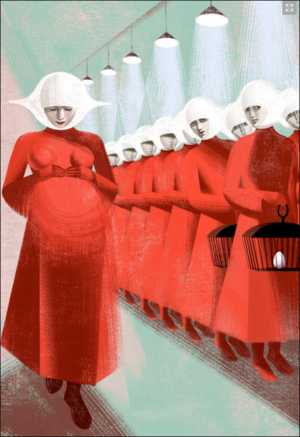

Indeed, science-fiction is closely linked to dystopian literature. However, Margaret Atwood is one who is breaking this mould. Atwood refused to class her novels as science-fiction, commenting that “Science-fiction has monsters and spaceships; speculative fiction could really happen.” What divides speculative fiction from science-fiction is that science-fiction contains things that don’t exist. This idea was later explored when Atwood added that speculative fiction “means a work that employs the means already to hand” – it is for this reason Atwood’s dystopian novels, such as A Handmaid’s Tale, are that more real and that more worrying. The fact there is no new technology in the Republic of Gilead (where A Handmaid’s Tale is set) that doesn’t already exist in today makes it that more unnerving; the society isn’t one based in the future, but one in the present and shows that such worlds are indeed, very possible. Atwood herself acknowledges this situation as a sad reality, saying “It’s a sad commentary on our age that we find dystopias a lot easier to believe in than utopias.” Perhaps this is speculative fiction’s effect, it makes these dystopian worlds more relatable and real, therefore making a society more aware of what is going on around them. By the end of such a realistic depiction of a dystopia, it can often leave readers wondering if we are living in a dystopia.

Eco-dystopias

Atwood also believed her novel, Oryx and Crake classifies as speculative fiction, however others have additionally dubbed it an ‘eco-dystopia’, another example being Harry Harrison’s, Make Room! Make Room! Harrison’s novel describes the consequences of population increase within the overpopulated city of New York. It describes how “mankind gobbled in a century all the world’s resources that had taken millions of years to store up, and no one at the top gave a damn or listened to all the voices that were trying to warn them, they just let us overproduce and over-consume until now the oil is gone, the topsoil depleted and washed away, the trees chopped down, the animals extinct, the earth poisoned, and all we have to show for this is seven billion people fighting over the scraps that are left, living a miserable existence – and still breeding without control.” This overly elongated sentence depicts a world with an endless amount of consequences as a result of overpopulation, and what’s worse is that it’s not being confronted properly. With the world’s population already over seven billion and issues such as global warming and sea level rise now a very real issue, aspects of Make Room! Make Room! ring very true today. So perhaps dystopian literature not only expresses political fears, but also environmental fears – fears that will become ever more relevant as time continues.

Raise awareness

Indeed, one must still acknowledge the political issues that so many dystopian works address. They tend to offer an exaggeration of our fears, acting as an extension of society’s socio-political issues. Orwell’s classic, 1984 raises concerns over totalitarianism, surveillance and censorship. It depicts a bleak outlook of life describing that “If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – for ever.” It offers a possible indication of the future if totalitarian states continue to exist. Orwell is also a worryingly relevant voice today. When Kellyanne Conway coined the phrase “alternative facts” regarding the inauguration’s audience size in an interview in January 2017, 1984 sales soared and became the sixth best-selling book on Amazon, and Penguin publishing struggled to print more copies for the increasing demand. People began to compare Conway’s phrase with Orwell’s “Newspeak”, a language that limits free thought. Real world events heavily influenced his work, he witnessed atrocities of fascist totalitarian regimes in the Spanish Civil War, as well as the rise of Hitler and Stalin; his experiences and surroundings also inspired his politically driven novel, Animal Farm which expressed his concerns about communism. One can also relate 1984‘s extreme surveillance with the present day whereby in 2013, following Edward Snowden’s story regarding the NSA’s mass surveillance, the novel saw a huge rise in sales of over 5,000%. In this case, one could argue that in light of recent political events, dystopian literature can be used as an object to draw comparisons with society’s problems today. The rise in sales for such dystopian fiction is also a reflection of our fears whether that is surveillance or lies being given by the government. How do audiences perceive such novels? Perhaps these novels offer an unusual sense of comfort to their readers that despite all society’s faults, it is not that bad as the world depicted in the novel; or perhaps it is to raise awareness to the possible future if we leave these issues unresolved.

It is also important to recognise that beyond the recent rises in sales for dystopian fiction, there has been a significant amount of young-adult fiction being published in this genre. This includes series such as The Hunger Games, and although much more action-packed, socio-political matters are still being raised. Dystopian literature can be seen as a tool to educate the younger generations and therefore make them more responsive to political issues, and with the huge access to information from social media for example, this may be likely. The Hunger Games, for example has twelve districts, all differing in wealth. The higher districts such as one and two are extremely wealthy; the lower districts like twelve and eleven are very poor and are exploited by the Capitol. It is evident there is a clear line of inequality within the story. It is no surprise that the first book of the series was published in 2008, in the middle of the financial crisis. There is great importance, one can argue, for the rise of dystopian literature in the young-adult world since these stories are a source of political ethics. A young student cannot be engaged by a textbook, however a dystopian story such as The Hunger Games, which is more exciting, can be a gateway to introduce societal issues to teenagers. George Orwell could have written an essay on the dangers of communism, but instead wrote an allegory of it, Animal Farm, which became much more popular than an essay could ever have been. Hence, dystopian literature is a better way of putting across a point than for example an essay since the story is what grips the reader, therefore making them more able to learn from it and the questions it raises.

Actions as a whole

Dystopian literature tends to end very bleakly with very little being achieved, although this isn’t always the case. Nevertheless, either way, the actions by a society as a whole, rather than the actions of the few are fundamental to change, or lack of it. The Hunger Games is an example of a successful rebellion in which people unite to overthrow the Capitol. However, not all dystopian novels tend to demonstrate a successful revolution. John “the savage” in Brave New World, by Aldous Huxley, fails to start an uprising, or at least some sort of reaction to the soma-reliant society (a drug the whole society takes to escape reality) by disrupting its distribution to the lower classes, the “Deltas”, saying “I come to bring you freedom”, but fails to do so. The fact he has no one to help him in this rebellious act highlights how important a unity of purpose is against such controlling states as depicted in Brave New World.

A similar example is found in A Handmaid’s Tale, when the Constitution was suspended, “There wasn’t even any rioting in the streets. People stayed home at night, watching television, looking for some direction. There wasn’t even an enemy you could put a finger on.” In this case, it is the apathy of the nation, this lack of action, even by a single person, which leads to the religious control in the novel; nobody asked for answers in this chaotic situation and the society pad for it. A Handmaid’s Tale shows how vital initial action could be to prevent somebody from exploiting the fear of the situation.

However, Yevgeny Zamyatin’s novel, We, a classic dystopian that inspired both Orwell and Huxley in particular, there is a sense of optimism surrounding rebellion at least: “There is no final one; revolutions are infinite.” Although, later the OneState may have survived, the novel ends with a doubt that it perhaps may not, with parts of the Green Wall surrounding the city having been broken for example, as if the cracks are beginning to show in this totalitarian society.

What has been established is that there are far more purposes to dystopian literature than it being a mere warning. All one can conclude is that this genre is becoming worryingly relevant and therefore needs more attention. At the Women’s March in Washington, a protestor held up a sign that said: “Make Margaret Atwood fiction again”, showing the real relevance of dystopian fiction. With a climate change-denier as President and nationalist political parties on the rise in Europe, one can view such a political landscape as indeed a very susceptible one to the depictions of dystopias. However, one must note dystopian fiction is a very new form of literature and has many forms, and so it might be a while before many academic journals are made about this genre.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Art imitates life. In the 50s and 60s it looked like the sky was the limit for what humans could do. America sent people to the moon, Britain and France were building a supersonic airliner, ordinary people were increasingly able to afford their own cars, homes and televisions, and diseases were being wiped out.

50 years on, even computer technology is beginning to look like it’s getting stuck in the mud, space flight is too expensive, supersonic airliners are too expensive, anti-vaxxers are reversing our progress on disease, antibiotics are losing their effectiveness, and corporate greed as well as overpopulation and migration threaten to reverse our gains, and the threat of environmental disaster looms over us.

The most successful life forms are the pests, scavengers that can breed quickly and exist on very little. Rats, flies, cockroaches, weeds, mold. Ugly life forms that simply adapt and survive. The same is ultimately true of humans, and those humans who are most rat-like will inherit the Earth.

Nailed it.

“Rats, flies, cockroaches, weeds, mold. Ugly life forms that simply adapt and survive. The same is ultimately true of humans, and those humans who are most rat-like will inherit the Earth”

Now this really caught my eye. Beautifully put. Applause, bravo!

And who creates and maintains the environmental conditions that make this so? Not nature: we do.

Dystopian work are interesting because they imagine a world where (usually) everything has fallen apart, and we watch how people try to survive.

The signs of dystopia are everywhere. the writers of novels, movie scripts, video games are just picking up on and exploiting our fear of a dystopian future.

You only have to look at one of the great dystopian novels / films ‘1984’ and look at how accurate that seems to be.

Sometimes so accurate it’s scary.

It’s hard to go past McCarthy’s romp, The Road, the perfect book-end to Blood Meridian.

Brilliant article. Look at the popularity of The Purge. So timely discussion with the feeling that we may be living in the dystopian present.

I’d like to write a novel about a Green Utopian future where human beings have learned to live ingenious and fulfilling lives y co-operating with one another on an equal basis to nurture and service the environment which sustains them in a magical productive and happy sustainable culture. Technology would be advanced so far that it works seamlessly with the natural world.It would not be boring.

There would be political challenges and battles with mad marauding criminals, nutcases and psychopaths. You would still have heroes and villains.

Human nature will still be the same, it would just be handled differently. Fighters would be defending and developing something more imaginatively civilised and optimistic than the way we live now.

People are more prescient than they would dare to contemplate, and fiction too often foreshadows the reality that is fast approaching. The closer it gets the more compelling these fictions become.

Dystopia is always a reflection of our current fears. In films spectrum, when youth was exalted we got Logan’s Run, when medication was the answer to all our problems we got Equilibrium, when we worried about women choosing careers over motherhood we got Idiocracy, reality TV gave us The Running Man, etc., etc. It’s just about pushing the current situation to it’s absolute extreme and considering what that would do to humanity and then how individuals rebel against or exist within the system. My favourite recently was the Planet of the Apes reboot in which the rebel came from another species. My least favourite Elysium in which even Jodie Foster had become a fascist dictator. That’s a really bad future.

No, The Running Man was written by Stephen King, using the name Richard Bachman in 1982 before all the reality television shows. The movie does not stay true to the book which is why the later movies based on King’s novels are much better as he has had control over them.

It’s almost like holding a lens up to society as a warning – forcing us to look and thinking ‘this is what could become if we keep heading in this direction’…

Fiction that are set in the future are usually of the science fiction genre. These films usually require some kind of adversity in order to allow the introduction of a hero figure. The adversity usually takes the shape of some kind of oppression… which is why the future is generally depicted as bleak.

Very true, hard to imagine a SciFi constructing a story without there being some sort of struggle.

Some SciFi also draws on history, which is also quite bleak. Post apocalyptic stories … the clue is in the subgenre.

While they may be set in the future, the best sci-fi stories are always about the present.

Something that is very clear in the works of Ursula K. LeGuin – which serve predominantly as commentary on issues of a recognisably human nature discussed in non-real settings…

Try some of the Culture books by Iain M. Banks – no oppression, plenty of action and laughs, clever ideas and so on. Of course, there is some adversity, but it’s all about as Utopian as it gets.

It’s true that there are a lot of sci-fi dystopias, but dystopian literature can be in pretty much any genre. For example, 1984 (the quintessential dystopia) isn’t really science fiction. If you want an example, something like The Bartimaeus Trilogy could be a dystopia, because of the way that magicians have created a class system.

All interesting points. Dystopian literature not only serves to allude to societal problems and fears of the era in which it is written but also fascinatingly, as illustrated by your Kellyanne Conway example, to reveal concerning patterns and issues in our present.

I think the appeal of dystopian stories lies mainly in two things:

1. It makes the present more palatable, as in ” Okay, times are tough, and the world sucks, but at least it isn’t THAT bad”.

2. Giving a focus for present, real-world anger to be aimed at.

We know there are bad guys (terrorists, corporatists, bankers, politicians, etc) in the world who are doing things make their lives better and ours worse, but identifying who is doing what is very difficult.

Dystopian stories provide a clear face of the enemy, usually unalloyed.

In real life it isn’t so easy and clear-cut. The bad guys have redeeming qualities, their motives are obscured, they do nice things occasionally to keep us off balance, and hell, be honest: our income, our credit, our lives depend on them to one extent or another. It’s very hard to really go against the bad guys when they control so much of your life.

Dystopian stories make it easier to bear, allowing us to jeer the bad guys and cheer the rebels, acting out our dissatisfaction with current reality in a safely vicarious manner, coming away with the feeling that somehow, somewhere, somewhen, the bad guys will get their due…all illusory of course, but still a satisfying anodyne against the current and real dystopia we experience every day.

As to why, well, quite clearly they are fulfilling a need on the audience’s part (the mediocre/bad films) or they are trying as best they know how to illustrate the dangers of particular courses of action or inaction (the good ones), and offer possible ways to prevent those horrifying visions from becoming reality (the great ones).

Absolutely. Not to mention the fact that dystopian settings are ripe for heroic sacrifice and valor, breeding grounds for identifiable, relatable protagonists. Some of my favorite novels are of a Dystopian nature, but more because the characters they produce are of a calibre that fascinates me than because of the setting.

Those that rule over us, know about the collective power of the human mind. By constantly painting a horrible future, they are in effect hypnotizing us into not only accepting such a future as inevitable but subconsciously helping us dig our own graves. The human imagination is a very powerful thing and when millions of people share the same vision of the future, they will help to birth it into being.

So all sci-fi writers, film directors and screen writers are all in cahoots with “the man” in an evil plot against humanity? Does that include the well documented anti-government Philip K Dick?

The message of Fahrenheit 451, book and film.

Artists are intuitive and they see what’s coming. The signs are everywhere: increasing technological enslavement, high-tech wars of various kinds, barbarism, manipulative false-flag operations and the endgame: a race of masters over a race of debt-ridden wage-slaves. The politicians no longer talk about a ‘rosy future’, only of increased ‘security’ and more wars that we will, of course, win, but never conclude.

There’s an established intellectual tradition that suggests art moves in a cycle, through heroic epics, romantic quests, melodramatic adventures to ironic dystopias. The notion of the ironic dystopia is seeped in a loss of faith in the present, such as the abandonment of religious belief, the collapse of the notion of heroic nobles, and the ridiculing of the norms of the current society. These films / TV series reflect a general dissatisfaction with current conditions, regarding the loss of faith in the building blocks of a civilisation as permanent, positing greater and greater horrors as civilised aspects of society crumble into hedonism and/or coercive control.

These societies are inhabited “ironic characters” who are happily living in a society that seems right to them (they are ironic because they are trapped within a system they cannot understand or escape from), while obvious to us, the knowing audience, are the horrors it contains. One such character “awakens”, playing the role of the audience aware of the horrors of such a society and fights against it. This “ironic awakening” can be comic, with the hero eventually transforming the aspect of the society that generates the horror and being welcomed back into it, or tragic, in which the hero’s fight ends without success (e.g. Decker in Blade Runner), at the cost of their own life (e.g. Neo in The Matrix), or suffering great cost to their family and friends (Buffy the Vampire Slayer). The character should be nothing special in traditional “heroic” terms, not a noble or god, but a commoner who’s slightly different to the norm.

The intellectual tradition posits a rise in dystopian art as the civilisation continues to decline, prior to a period of renewed faith and return to more traditional religious values. I believe there is a movement called metamodernism that is positing this is already happening, citing evidence such as the Stuckist Manifesto, the New Weird Generation and the renewalist movement in the church. Place this against the dystopian and ironic art that this article draws attention to and we are in some interesting times.

Sci-fi dystopias reflect an erosion of social democracy from the late 20th century onwards.

What works best about for example Handmaid’s Tale is that it’s not too far removed from reality, and it’s sinisterly easy to see how a large drop in fertility rates could get us from here to there. The MaddAdam series were similarly built from our world but depend on technology more so it was less relatable. (Just focusing on dystopias here because, y’know, the world right now)

Dystopian fiction are popular because the future is bleak from a sociological point of view – it’s been ongoing for the last 50 years or so – can’t you see it? There are issues that have always been present: poverty/lack of food or water/extreme weather/loss of species/slavitude to technology and hoping it will fix the problems including endemic violence. If anyone can prove these issues are on the way to being resolved please let me know. Dysfunction seems to be the name of the game. I do believe The Road book/film comes closest to what we can expect in the future (and I’m an optimist!).

Dystopian literature is probably my favorite genre to read. The most recent book that I read, Ready Player One, certainly qualifies as dystopian fiction. Another recent example would be The Circle. Society and advances in technology are making these fictitious stories more and more relevant each day.

Dystopian fiction is a product of people who live in a stable society wishing to explore what happens outside of one.

Most of these writers have nothing interesting to say, either about the past, the present or the future. Certainly the YA stories are nothing more than crude melodramas. But the future is easier to write about because it’s unknown. There’s greater freedom and less responsibility.

I love, love, love dystopian stories – and I think that a huge component of this is what makes people respond also to “disaster/apocalypse” films – it becomes about the innovation and durability of the human spirit. Dystopian films provide a framework of unreasonable rules that the protagonist can stand against, and most often they are surmountable challenges. I think often in our real lives we face the dystopia of our own world and heave a sigh of ‘what can I do?’ Whereas dystopian literature, in particular rather than film versions, provides a direct issue that reduces human rights that can be acted against. I think it is like most “thematic settings” for literature in that it provides a framework for a protagonist to work against rather than simply existing within, which is what creates their role as the protagonist and change-bringer. Another great classic dystopian is ‘The Chrysalid’ by John Wyndham, and if you want a YA version of the same story also ‘Obernewtyn’ by Isobelle Carmody.

Dystopian? Because bad news sells. Because people invented religion to cope with their mortality, the inevitable end. No future. For YOU. Almost all religions deal with some sort of apocalyptic end time. And in our ‘secularized’ world view, hell has been replaced by climate catastrophies or global diseases and the lot.

Dystopian literature has been very reflective of the problems society is facing today such as with the environment. Blade Runner is a perfect example as it shows a world where every natural resource has all but been exhausted and using replicants to show how that technology may become greater than humanity.

A big part of dystopian literature is being able to find a happy end or a solution to the potentially realistic problems. By examining a hypothetical scenario, it sheds insight on how to tackle real-world problems.

I thought this was very interesting. I personally loved the way you connected other books to use as examples that allowed the readers and audience to look at the reason and purpose of dystopian literature. Good work!!

I have a few more dystopias to add to my reading list now! I truly love the genre and this was a nice read.

It’s so important to bring dystopian literature to the forefront of study, as I believe it is one of the key indicators of a society’s struggles, biases, and human experiences. So much can be interpreted from these texts, and you do a great job summing up some of the keystones of the genre. Love this!

As someone who would have once have chosen to live in the past without a question if someone had given me the choice between the past or the future, I have realised that my choice had reflected on a very limited and fearful worldview. I now realise that fear of the unknown is greater than the fear of the knowledge that some of the worst aspects of humanity have already been perpetuated in our history. Thus, dystopian fiction is brave to write, as it requires the author to take certain unsavory aspects of humanity and evolve it, for humankind is constantly evolving – a feat which would be mentally and emotionally taxing – and brave to read, as it no doubt adds to today’s current sense of crisis. Readers realise that our world of hypernormalisation leading rise to quite a few of the iterations of the distopian futures provided could very well prove a viable possibility.

In any case, I would now choose to live in a possible future, aware of my own and collective fears, a gamble I would be willing to take just for the thrill of it. Anyone else with me, or kindly disagree?

I believe you are right about the lack of scholarly introspection into dystopian themes. Yet, the literature abounds and you didn’t even mention Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury which seems to fit into the destructive agenda of such movements: television surveillance in 1984, book annihilation in Bradbury–what’s next, hijacking and commoditization of human thought? Someone should write on that part.

The purpose of dystopia is to set a stage of conflict and struggle so filled with props for the author to quickly put words on the page without us noticing it’s essentially worthless prattle. So as the cost of bringing a book to market have dramatically dropped so has the desire for easy to write books increased in the sausage factory that is modern dystopian writing.

I love dystopian novels-especially the new wave of YA dystopian (Hunger Games, Divergent, and Maze Runner among my favourite). I agree with the various points in the article concerning the purpose of DF. First-the warnings of certain types of governance; the moral lessons, etc. What fascinates me the most is how authors imagine their characters overcoming or dealing with the dystopia. For instance, Tris of Divergent and Katniss of Hunger Games are both successful in leading a rebellion (albeit reluctantly). It is interesting that they do a much better job of doing what needs to be done than other male protagonist in other DF novels or stories (looking at you, Thomas). Just some of my opinions. Great article!

Distopian futures resonate with many of us because, even in cold hard light of a sober morning, it’s not difficult to imagine a distopia in our future. Nearly every major indicator of environmental quality has plummeted sharply in the last 50 years. It’s no wild leap to imagine a dark future. For us it is somehow comforting, even inspiring, to face that darkness and realize that our future might not be as dark as some writers have imagined.

It is interesting that Margaret Atwood’s rejection of the label ‘science fiction’ for her novels is actually at odds with the general perception of readers, an indicator that regardless of the position of an author on the nature of their work, it is the public who define it – even when bookshops put it on shelves in other categories. An example of this can be seen in the comments on this Guardian article: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/oct/14/margaret-atwood-road-to-ustopia

I think creating young adult dystopian fiction has been a great idea because it helps young adults question things and form political minds of their own.

“Make Margaret Atwood fiction again”…how utterly harrowing.

The inception of Atwood’s novel as a current popular TV series certainly highlights how the same narratives about gender still exist in society today. I agree with the broad-reaching “speculative fiction” umbrella the novel fits under as the banality of the story is its inherent power.

Distopian literature, unlike dystopian spelling, is absolutely necessary, always. It causes readers to stop, think, pair, share about life and the world.

Dystopian works are interesting because most worlds find a real life problem and exacerbate it beyond belief. This demonstrates the possibility that the world could become this dystopian way or how it is already similar to this. It makes audience members think about the problems in real life that could become a much larger problem, or how an issue is masquerading as small when it is impacting lives in a major way.

The importance of dystopian novels are definitely to help readers wake up and open their eyes to situations around them. The effect that they can have on a society is rather incredible–especially when a book or movie becomes popular. However, I do not think that this is a new genre. Books and movies discussing topics such as these have been around since at least the 1920s.

It’s interesting to note that not only is there a “real world” inclination to produce dystopian fiction, but also a narrative one as well. Utopian novels are far and few mainly because of the difficultly of constructing a compelling narrative without conflict.

‘The Natural way of Things’ (Charlotte Wood) is particularly terrifying in its presentation of a kind of tomorrow-dystopia, where the action takes place very much in the present. This kind of dystopia is extremely well placed to raise awareness about current issues.

The last part about action reminds of the internet trend of keyboard warriors. Everyone seems to be unsatisfied with something, whether its a politician, the economy, whatever, yet no one is attempting to make real change. The person just waits at home for someone else to do something. I do not believe that simply wanting to change something is enough, i understand its much more complex then that, but it is simple my observation on the trend of angry online mobs.

It is both strange and also understandable as to how dystopias are far more commonly written then utopian fiction. Any story, whether taken place in an Orwellian future or in the present day, is created through conflict. The whole of the formation of a corrupt, dystopian society is built off of conflict. Also, dystopias mirror concerns of the author, as well as fears that writers and readers could have about the future. For instance, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 highlight’s the author’s concern regarding censorship and how that could lead to a lack of individual thought and discussion. ironically, Fahrenheit 451, as well as many other dystopian classics, have been heavily challenged in many schools around the country.

I find that dystopian fiction tends more around science fiction, and includes technological advances that can be hard for people to imagine ever existing. However, I was very intrigued with your inclusion of A Handmaid’s Tale in the dystopian fiction genre. The lack of technology in that piece actually shows how history can repeat itself, and how some society’s resort back in time. I also find this interesting, because this also makes the dystopia in A Handmaid’s Tale to seem more like a present dystopia. it also shows that even without technological advancements, corruption and suppression can still occur. Fascinating piece and i would recommend others read this.

It’s scary to know that some dystopian novels seem to be coming true. I praise the authors for being observant and insightful about their surroundings but also having the ability to articulate what they observed.

Dystopian works have a vague sense of realism to them. Most people of society imagine the future to be a happy and peaceful utopia but they fail to recognize how their immediate surroundings are often the opposite. I think fiction is consumed because everyone wants to hold on to some form of hope that one day everything will be fine. Maybe this is to justify how we are leeching the resources of this planet without a care. Dystopian prospects often hold up a mirror to the innate desires and greed of humanity and are therefore a very important literary genre.

Dystopian literature has one point: to make a point! The article, “What is the Purpose of Dystopian Literature?” aims to answer this question. However, the problem with answering this questions is that the answer is too obvious for the reader, at least from this humble reader’s point of view. Dystopian literature is a warning to a political ideology that seems too drastic, and this is an idea that is not new because it is coming from this article. Moreover, it is the obvious point of dystopian literature. However, in another sense, it is also asking its readers not to be sheep; otherwise, a dystopian future is not too far along. So, the purpose of this writings is to think for ourselves and to warn us about the possibilties of extremes.

Very nice article, really got me thinking. Great examples too, including a few I have yet to read and am now looking forward to. I have always thought that one of the most intriguing things about dystopian fiction is how characters choose to act or behave and sometimes evolve in the absence of conventional societal rules.

Fantastic overview of dystopian literature and a great introductory read for anyone new to the genre.

Interestingly the nineteenth century was abound with ideas of utopianism due to the overall optimistic progress of humanity (social welfare, abolishing slavery, rise of knowledge and rationality, enlightenment, etc). So why this shift from utopia to dystopian culture in our modern times? The 20th century happened (with all its horrors i.e WWI, WWII, holocaust, gulag).

Perhaps the dystopian cultural worldview is rooted in our fear of repeating the horrors of the last century, so much so that any alternative of another ‘utopian world’ is immediately struck down, thus creating the dilemma: what then is to be considered progress? This I think is the deadlock of dystopian writing for our modern times.

Thank you for this. I’m teaching a dystopian fiction course in a few weeks, and this article puts a lot of things I’d like to say into focus.

Enlightening read, I think I’ll have to return to this article quite a few times to fully digest. Thank you! 🙂

I liked your analysis of dystopian literature not only as an expression of political fears, but also environmental fears – fears that will become ever more relevant as time continues.

As an ecologist working in conservation I’ve found a strange comfort in dystopian fiction….living and working in Myanmar in 2016 I devoured George Orwell and found it enlightening not only for what it is, but also as a way to understand the author and some of what he learnt from his time in Burma. I’ve also found solace in Atwood – both authors reflect on hierarchies in society and the complexity of people and their inner lives.