Philadelphia and AIDS: Looking Past the Pedantry

Philadelphia and Its Time

It was 1993, and AIDS was terrifying. In the eleven years since the syndrome got its name, hundreds of thousands had died around the globe. The cause was HIV, a virus spread through bodily fluids, and it disproportionately targeted gay men, injection drug users, the poor, and whoever found themselves on the wrong side of some societal divide. AIDS couldn’t be cured, and it usually couldn’t be kept at bay for very long. It would be another three years before the release of HAART, the antiretroviral cocktail that extended the lives of millions with HIV and delayed the onset of AIDS, often permanently. For the time being, there was a lot more fear, anger and misery than hope for those who had the virus.

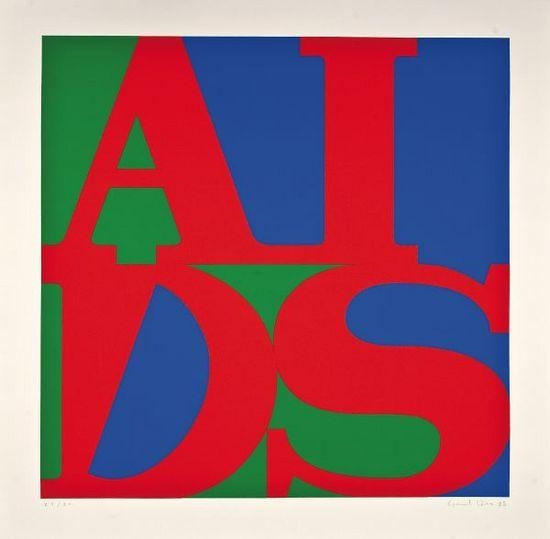

For a decade, the masses of the AIDS-afflicted and AIDS-affected across North America had been marching, chanting, storming conferences, offices and government buildings, demanding attention, representation, and care. Out of the movement sprang a profusion of visual art, street theatre, and dramatic and documentary film, often combining brutal honesty with bold-faced camp. Art collectives like Gran Fury and General Idea pasted America’s cities with ferocious, eye-catching posters that turned Robert Indiana’s “LOVE” graphic, a quaint, oddball relic of the sixties, into “AIDS,” or pronounced “Silence = Death” under the pink triangle that marked homosexuals in the holocaust.

In the meantime, for millions of the uninfected, AIDS was first and foremost a thing to be avoided: physically, politically, and in tasteful conversation. In the mind of conservative America, this disease, which destroys the body’s ability to resist infection, came to represent the scourge of urban squalor. Misinformation, paranoia, and prejudice abounded.

Some independent films from within the gay community, like 1986’s Parting Glances, touched on the experience of living with AIDS and garnered some critical attention, but did not break through to the mainstream. Meanwhile, the AIDS Memorial Quilt, begun in 1987, made use of tropes of American domesticity to incorporate AIDS into the popular conception of the national identity.

Then, a year after the quilt’s third appearance in Washington’s National Mall, Hollywood decided it was time.

On December 22nd, 1993, TriStar Pictures released Philadelphia, the story of a gay lawyer, played by Tom Hanks, who is fired when his employers discover he has AIDS, then takes them to court for wrongful dismissal.

The origins of the film are not without controversy. Its director, Jonathan Demme, had faced accusations of homophobia and transphobia for his previous film, Silence of the Lambs, in which a gender-bending serial killer murders women so he can wear their skins. Keen to clear his name, Demme prudently acknowledged the shortage of positive gay characters in films and enthusiastically set to work with screenwriter Ron Nyswaner on the project that became Philadelphia.

Officially, the story was an original conception by Demme and Nyswaner, drawing from a number of real life cases. However, several scenes in the film led the family of a deceased New York lawyer named Geoffrey Bowers to claim that the screenplay constituted a misappropriation of his life story. Bowers had died of AIDS in 1987 in the midst of a courtroom battle similar to the one in the film. The lawsuit between the filmmakers and the Bowers family was settled in 1996.

The Critics

Philadelphia was a huge deal before it even came out. As one critic for Out Magazine wrote, “for the gay community … Philadelphia was the most eagerly anticipated movie in the history of the medium” (qtd. in Zelinsky 20). Many were thrilled to see a studio putting tens of millions of dollars on the line to tell the story of a gay man suffering from AIDS. When the movie came out, it was widely lauded by the critics, going on to rack up nominations and awards for the film, the screenplay, the acting, and especially its opening song, “Streets of Philadelphia,” written and performed by Bruce Springsteen.

But for some critics and activists, Philadelphia did not live up to the hype. Soon after its release, voices began to come from within the AIDS-conscious world, calling it “a bad film, a missed opportunity [that] misrepresented gay men and the experience of living with AIDS” (Sendziuk, 2010:444). Perhaps the loudest critic was writer and gay activist Larry Kramer, who called it “dishonest… often legally, medically and politically inaccurate” and declared, “I’d rather people not see it at all” (1994). In the years since its release, these voices of condemnation have become the dominant force in academic evaluation of the film. Today, any student who comes to Philadelphia through a class on film, HIV/AIDS, or queer representation will encounter the movie chiefly, if not exclusively, in terms of its failings.

Problems of Representation

The main thrust of the criticism is simple: Philadelphia is about AIDS, but it does not get AIDS right. This evaluation is basically a fair one. The plot of the film sees a desperate Andy (Tom Hanks), rejected by nine different lawyers, turn to the homophobic Joe Miller (Denzel Washington) for representation. This premise blatantly ignores the “world of services, advocacy organizations, and personal relationships” (Schulman, 1998:49-50) that sprang up to fight AIDS within the gay community when straight society failed to help. Moreover, the disease’s representative in the film struck many as a decidedly imperfect one: Hanks’s educated, well-to-do Andrew Beckett, supported by a loving family throughout his legal battle against oppression. As the movie’s only non-peripheral HIV-positive character, Andy seemed a poor reflection of a condition almost always associated with isolation, disenfranchisement and ostracism, and that, “by 1993… had become a disease of the poor, heterosexual women of color, and drug users” (Sendziuk, 2010:445).

Beyond demographics, Hanks’s character is dramatically generic, defined by little more than what Roger Ebert praised as his “vast ability to give and receive love” (1994). Of course, Tom Hanks is perfectly cast here, already well on his way to becoming Hollywood’s human embodiment of the wholesomeness of middle America. Rather than showing us a tangible human being with AIDS, Philadelphia does everything it can to shape Andy into America’s ideal AIDS patient, triumphantly normal in spite of this horrifying disease and in cozy counterpoint to his non-normative sexual orientation. He is totally saturated with love of home and family as he holds a bottle to a baby in his parents’ living room, declaring “I love the law” in his inspiring courtroom monologue. In a ham-fisted attempt to fill the void where a personality ought to be, Demme and Nyswaner have Andy singing along to an opera record, visibly overcome with emotion, as he breaks from preparations for his climactic testimony.

As for Andy’s sexuality: what sexuality? Andy is gay, so we are told. Indeed, he even has a sexy Spanish boyfriend named Miguel, played by Antonio Banderas. But with no kissing, no shared bed to speak of, almost no visible or audible intimacy between them, and very little shared screen time, it’s hard to call this a substantial filmic depiction of a gay couple. If one missed a few lines of dialogue, the two men might seem nothing more than a pair of especially close roommates who at one point dress as sailors and slow dance together. Clearly, on the representational front, Philadelphia leaves much to be desired.

Pedantry and Vacuousness

Of course, these liberties and omissions serve a purpose. Philadelphia is unabashedly didactic. Director Jonathan Demme stated that his intention was to make a movie “for people like me: people who aren’t activists, people who are afraid of AIDS, people who have been raised to look down on gays” (qtd. in Sendziuk, 2010:446). As a teaching exercise, Philadelphia pursues two parallel projects: first, to dole out some of the basics of how HIV/AIDS works: no, you can’t get it from shaking hands, as Joe Miller’s doctor tells him. No, you don’t need to be serially promiscuous to contract HIV, as Andy’s story establishes, etc. Denzel Washington’s character puts it best in his courtroom mantra: “explain it to us like we’re four year-olds.”

Secondly, the film strives to demonstrate the humanity of people with AIDS in a broad sense, mobilizing what Robert J. Corber calls “sentimental politics” (2003:111) to force the audience to sympathize with these blameless sufferers. Demme’s movie aims to make emotional contact with, and teach a lesson to, a large audience, much of which might never before have agreed to give the AIDS crisis the time of day. In so doing, it attempts to take the first step toward normalising a disease that was often regarded as all but unmentionable. This undertaking, far from an exhaustive or even totally accurate study of AIDS, was nonetheless a substantial one in 1993, in the wake of the “Reagan revolution” that so shaped America’s moral and aesthetic “mainstream” while ignoring AIDS almost completely (Capozzola, 2002:98). So Demme made his decision: “I didn’t want to risk knocking our audience back twenty feet with images they’re not prepared to see” (Decurtis, 1994), which apparently included almost any expression of romantic love between men.

Philadelphia is decidedly not a work of the AIDS activist art of the ’80s and ’90s that brimmed with both anger and originality. Instead, as a moralistic melodrama, the film stands in a complex and problematic relation to the truth, at once approaching and escaping it, ultimately arriving at what Richard Cante calls “a particularly disturbing combination of qualities: pedantry plus vacuousness” (1999:253).

Re-examining Philadelphia

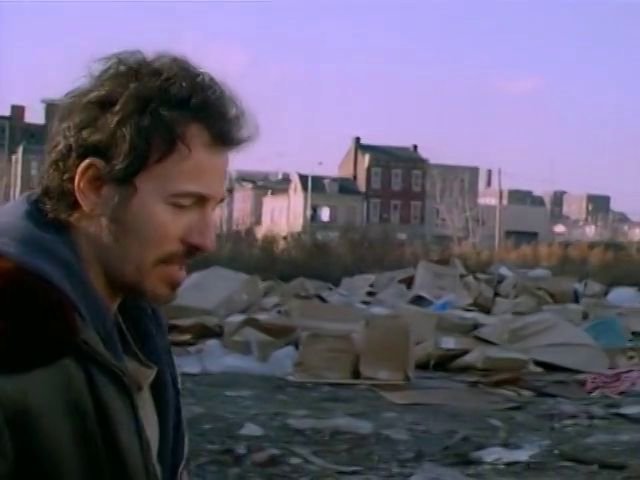

The flaws of Philadelphia are many and obvious, but it is not totally without merit. The most beautiful sequence in the movie is the opening montage of Philadelphia street life on an autumn day. This living, documentary-style mosaic introduces the viewer to the city’s diverse aspects, both recognisable and particular: schoolchildren wave as the camera passes them along the street, cyclists glide through a city park, a youth on the corner flashes a peace sign, a homeless man huddles for warmth, all laid over with Bruce Springsteen’s aching original ballad, “Streets of Philadelphia” (Demme, 1993). The song’s lyrics imply a speaker with AIDS, but are never explicit: “Saw my reflection in a window and didn’t know my own face. / Oh brother are you gonna leave me wastin’ away / On the Streets of Philadelphia?” The sequence makes a series of statements, not about AIDS, but about urban life generally: that it is beautiful, that it is difficult, that it is worth examining, that we are all united in different forms of suffering, all flowing under the surface of day to day experience. AIDS, Demme here implies, is just another part of it.

Unfortunately, this hypnotic, unembarrassed vision of modern life does not last long. The music fades and Demme shoves us into a courthouse: a still-employed Andy competes with Joe Miller, later to become his own advocate, to win a judge’s favour in a corporate negligence case. Here, off the “streets of Philadelphia,” the real story begins. It is in this world of big city litigation, a world that offers up a tried and true set of narrative and cinematic conventions, that Demme and Nyswaner’s tale plays out. As a courtroom drama, the film becomes everything that its status as Hollywood’s first major treatment of AIDS might seem to preclude: a stylish, plot-driven movie with obvious villains and innocent but attentive bystanders.

The courtroom even gives us a sexy, energetic hero; the protagonist of this story, rather than the flatly idealized and sadly doomed Andy, becomes Joe Miller, who morphs from a closed-off homophobe into a hero of the city’s HIV community while forging a powerful bond with the dying Andy. As this story unfolds, the urban realism of the film’s opening recedes into a filament of grit that thinly attaches the lofty melodrama to the real world of “issues” like AIDS: occasionally, we return to Philadelphia’s mean-looking streets, or encounter one of the film’s recurring, visibly AIDS-afflicted extras. The realism is purely superficial. However, the discordance between the film’s opening and what follows does not negate the poignancy and underlying truthfulness of the film’s first two minutes.

The film that seems to be beginning when we see the “Streets of Philadelphia” sequence is a good one: an honest, uninvasive examination of the role of AIDS in American city life, uncompromising and yet oddly welcoming to a willing viewer. That isn’t the movie we get, but the very idea proposed here offers some redemptive value, as well as a glimpse of what might have been.

Problems of Form

Looking for the root of Philadelphia‘s flaws, an important formal predicament presents itself. As a didactic melodrama, Philadelphia necessarily insists on consistent narrative clarity. Just as the courtroom drama is shaped by the conventional necessities of dramatic perturbations and clear character motivations, AIDS itself becomes a discrete agent of causally coherent destruction. At one point, under cross-examination, Andy recalls an isolated hook-up in a porno theatre, evidently the night he contracted HIV. Here, not only is it implicitly clear where, when, and from whom Andy contracted the virus. It is also morally unambiguous what his fatal mistake was: having anonymous sex in a den of sin, far away in time and space from the warmth and sentimentality that are his natural habitat. His healthy, handsome, and presumably faithful boyfriend, meanwhile, is kept perfectly safe.

As Kelly Keating puts it, Andy “the ‘good homosexual'” who “believes in the traditional family and is involved in a monogamous relationship… contracts the virus only when he violates these ideals (becoming a ‘bad homosexual’)” (2009). To the filmmakers, the theatre scene contains essential background information. But to the informed viewer, it is fundamentally untrue to the intrinsic illogic of AIDS. This clumsy and morally dubious attempt to impose reason onto the naturally reasonless brings to mind the troubling words of one bereaved father, just a few years earlier, whose daughter died after contracting HIV at the dentist: “Her sickness would have been easier to accept if she’d been a slut or a drug user. But she had everything right” (Johnson, 1990).

In its mission to use the conventions of a melodramatic plot to engender sympathy, Philadelphia is at its dullest and most dishonest when it concentrates on this melodrama. But, as the “Streets of Philadelphia” sequence makes clear, neither the failure nor the artifice is absolute. Another scene, also a flashback from the courtroom, reveals the complexity and sensitivity that we see in the film’s best moments. An uncomfortable Andy sits in a sauna with the senior partners as they swap offensive jokes. One calls out, “Hey Walter, how does a faggot fake an orgasm?” Walter has heard the joke before, and immediately offers up the punch-line: “He throws a quart of hot yogurt on your back!” The bellies of the wrinkled, half-naked men shake with laughter.

Obviously, we see here the subliminal cruelty of these prejudiced men. But more interestingly, the scene reveals the tiredness of the ritual of institutional homophobia. The joke is both offensive and totally lacking in vitality, totally redundant, serving only to sink the old men deeper into their own blindness. Rather than laboriously demanding our empathy, the sauna scene actually enacts the intellectual and aesthetic demise of the assumptions that define the old, Reaganite guard. Philadelphia momentarily transcends the machinery of melodrama and comes alive as a piece of good, honest satire. It becomes what it should have been all along: an engaged narrative study of what it is we talk about when we talk about AIDS.

Again, the moment vanishes, and again we return to the courtroom and all that it entails. Philadelphia makes it obvious that the filmmakers want to take their subject seriously, and sometimes they even have something real to say about it. But the feeling never lasts. Time and time again, they snatch mediocrity from the jaws of insight. In the end, one almost forgets the good bits altogether. But the movie somehow convinces us that it deserves better. The question becomes, what do these instances of intelligence, and their rarity, tell us about the role of popular cinema in confronting AIDS?

The Outsider’s Gaze

Understandably, Philadelphia takes it upon itself to tell us a great deal. But when the film is thought-provoking, it is so because it engages the unflinching gaze of an interested outsider, rather than its usual, preaching pedagogy. It is the camera rolling past the living Philadelphia streetscapes, or the silent observer when the old bullies hold court in their white towels. As Hollywood’s first curious glimpse at AIDS, as Joe’s story rather than Andy’s, Philadelphia was always going to look at the disease from the outside. Viewers must make no mistake: this is essentially another movie made by, for, and about those who do not have HIV. Critics on the extreme end of Philadelphia-bashing might argue that this fact alone renders the film inappropriate from its conception. The movie, for its part, does much to fuel their condemnation. But its many flaws do not damn it absolutely, and the possibility remains that this outsider’s perspective was and is one worth exploring.

Demme’s defense is not to be disregarded: that the film had to be popularly palatability while protecting its audience from much of the reality of AIDS in order to have a social impact. While the film’s effect on the public is difficult to measure, there can be no denying that it has been widely remembered, often fondly, or that its content constituted something new and difficult for many of the millions who saw it. To this day, despite the excoriation that the film receives from academic pundits, many look back on it as a groundbreaking and important work of socially conscious cinema. Perhaps the sacrifices of narrative and historical quality made along the way were worthwhile, or perhaps not. Regardless, a re-evaluation of Philadelphia reveals mainstream cinema’s need, and at moments its ability, to honestly examine the AIDS crisis, rather than simply sermonising on it.

What kind of a film should Philadelphia have been? It seems that its greatest fault is one of self-identification. The movie purports to be realistic, then lapses into conventional Hollywood fantasy. It sells itself as the story of a hero with AIDS, then reveals a near total lack of interest in the experience of the AIDS-afflicted subject. Maybe the filmmakers should have gotten together and realised that this was not AIDS: The Motion Picture, not the tale of Andy Beckett, gay American hero. Instead, it was a story about the awkward and incendiary moment when one hitherto unfamiliar with HIV comes into contact with it, and sees the cultural clash that has long carried on around the virus.

An idea comes to mind: that Philadelphia should have been something like a picaresque, in which a troubled person journeys through a troubled world not quite his own. He struggles, he resists, he observes, and he is put to some kind of test. The audience, in the meantime, is asked to come along with him, to laugh at his foibles, and to see some part of the world anew.

As a didactic film about AIDS, Philadelphia is at best forgettable and at worst offensive. However, as a meditation on the American consciousness around the disease, it is, in part, worth remembering. This often bizarre and frustrating dialectic between pedagogy and contemplation brings one to an important plea for those who address AIDS through popular artistic media: Don’t just tell me. Show me.

Works Cited

Cante, Richard C. (1999). HIV, Multiculturalism, and Popular Narrativity in the United States: Afterthoughts on Philadelphia (And Beyond). Narrative, 7 (3), pp. 239-258. Retrieved from http://0-www.jstor.org.mercury.concordia.ca/stable/20107187

Copozzola, Christopher. (2002). A Very American Epidemic: Memory Politics and Identity Politics in the AIDS Memorial Quilt, 1985–1993. Radical History Review (82), pp. 91-109. Retrieved from http://www.econcordia.com/my2/coursedocument.aspx?course=hiv_aids&document=Radical_History_Review-2002-Capozzola-91-109

Corber, Robert J. (2003). Nationalizing the Gay Body: AIDS and Sentimental Pedagogy in “Philadelphia.” American Literary History, 15 (1), pp. 107-133. Retrieved from http://0-www.jstor.org.mercury.concordia.ca/stable/3567971

DeCurtis, Anthony (Interviewer) & Demme, Jonathan (Interviewee). (1994, March 24). The Rolling Stone Interview: Jonathan Demme. Rolling Stone. Retrieved from http://www.rollingstone.com/movies/features/the-rolling-stone-interview-jonathan-demme-19940324

Ebert, Roger. (1994, January 14). Philadelphia. RogerEbert.com. Retrieved from http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/philadelphia-1994

Hobbes, Michael. (2014, May 13). Why Did AIDS Ravage the U.S. More Than Any Other Developed Country? New Republic. Retrieved from https://newrepublic.com/article/117691/aids-hit-united-states-harder-other-developed-countries-why

Johnson, Bonnie. (1990, October 22). A Life Stolen Early. People, 34 (16). Retrieved from http://www.people.com/people/archive/article/0,,20113381,00.html

Keating, Kelly. (2009, November 11). The Absent Body: Felix Gonzalez-Torres, AIDS, Homosexuality and Representation. The Great Within. Retrieved from http://www.thegreatwithin.org/2009/11/absent-body-felix-gonzalez-torres-aids.html

Kramer, Larry. (1994, January 9). Why I Hated Philadelphia. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://articles.latimes.com/1994-01-09/entertainment/ca-9875_1_aids-movie

McClelland, Alex & Trudel, Genevieve (Interviewers) & Finkelstein, Avram (Interviewee). Silence = _____ [Interview transcript]. Retrieved from http://fusemagazine.org/2013/09/silenceequals.

Sendziuk, Paul. (2010). Philadelphia or Death. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 16 (3). Doi: 10.1215/10642684-2009-038.

Schulman, Sarah. (1998). Stagestruck: Theatre, AIDS and the Marketing of Gay America. Durham: Duke UP.

Zelinsky, Mark. (2015). The Philadelphia Phenomenon. Gay and Lesbian Review Worldwide, 22 (5), pp. 20-22. Accession number: 109151307

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I think it’s incredible how much things have changed over these 23 years. Being gay has become more accepted in society, to the point where the majority of the population, in the United States at least, is in favor of not only acknowledging gay people, but also same sex marriage as a positive, legitimate, and legal institution.

Not true. Only about three states have passed voter-approved gay marriage laws. The rest allow gay marriage via court decision or legislative approval. It is impossible to read the Constitution as a document banning the full rights of citizenship to a particular group without an a priori of some type.

http://gaymarriage.procon.org/view.resource.php?resourceID=004857

Nothing about this movie comes off as a masterpiece. It’s just cheap, cheesy legal melodrama. Tom Hank’s acting was wooden, and the script sounded like an 80’s PSA on AIDS and Gay people.

I was expecting some depth, but the film treated its audience like idiots. I doubt that people were much less enlightened about Gay rights than they are now. People go into debt going into law school because of movies like these, portraying lawyers as “heroes.” Why it won 2 oscars is beyond me (well, not really).

I just don’t know how the average person could sit through this film without rolling their eyes continuously. The movie may have had potential, but the execution is just dreadful.

Totally agree. Sappiest movie ever.One of the most stupid and hilarious moments is that overemotional moment when Tom Hanks just collapses at the end of the judgement.

I don’t generally fall for sappy sentimentality. But damn that last scene always hits me like a truck. The Neil Young music, the home movies. Sappy sentimentality done perfectly.

The thing that gets me about it is the shot of Andrew’s mother about to break down… and someone brings a kid over to her and she smiles… Neil Young’s song IMO was the one that should have won the Oscar.

I agree. A celebration of a life

This article is a real quibble. I’ve always enjoyed the movie and thought Tom Hanks executed the role impeccably, but reading through this article gave me a modern day perspective and now I feel the need to watch the movie again and notice the nuances I, unfortunately, missed the first time! Thank you for the insight!

Not real a gay film. but a brilliant demonstration about the force of values.

Composer Howard Shore’s ‘Precedent” is still one of the purest track I have ever heard.

My cousin died of AIDS back in 93. I think of him every time I watch this film. All his friends, well majority of them, were all gay. Some of the nicest people I’ve ever met.

I cry everytime I see it. I spend times with simple tears to all out craying like a baby. Its a heartbreaking film but so very necessary. I good film that has me to remember my friends. They are worth each and every tear I shed. God Speed to each one. I love all of you.

Philadelphia is Hanks best movie role ever, he shows the dignity of a man that no hope of a future. The writing was great, most of the acting is great except Washington who seemed to chew through scenes. It was 5 years after my brother died of aids before I could watch this movie, it is heartbreaking and it is mostly the truth about Aids and gay men.

The one thing that bothers me is that (based on the conversation between Charles Wheeler and his associates after being served by Joe Miller at the basketball game), they openly state among themselves that Andrew was fired for incompetence, not for having AIDS. In fact, only one of the associates apparently suspected that Andrew was sick. So does this make Andrew’s victory false, since he really WASN’T fired for having AIDS, but won the case anyway?

That’s always bothered me a little bit.

I always got the idea that they in fact didn’t know that he had AIDS from the movie. I’ve never read the book it was based from though, so it’s possible that in the book they did know he had AIDS.

One of a few movies that made me cry.

My God, there were some emotional moments in this film but the end literally slayed me, from the moment that Neil Young’s song starts to play, through the home videos of Andy (actually Tom Hanks according to the trivia section), and into the final credits. The song is incredibly sad, and contrasted with the innocence and joy of the videos, it’s a huge feat of emotional manipulation :P. I lost it and cried uncontrollably and was rattled for an hour afterwards.

The ending with the homevideos just seemed too manipulative and forcful. As if the director wanted to say “Look at this adorable little kid. That kid is now dead! Isn’t it sad!”

Would have been a much better film without it.

I understand your reaction, but remember that this film came out 20 plus years ago.

In 1993 it was much more necessary to come right out and convince a more socially-conservative audience that indeed, Andy, and other gay men and women, are generally just like the rest of society, along with adorable and innocent childhoods. Their lives are no less valuable than anyone else.

I imagine that sentiment is more ‘obvious’ today. When I saw it new in 1993 it was not.

This movie will probably eventually be looked at the same way Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner is now. That movie has a lot of the same familial qualities, in addition to being all about prejudice. It’s very of the time socially.

Saw this movie for the first time today. I liked the movie but I was still very confused as to how Andrew won the case based on the story as it was presented. The only thing that made me think they should win was when the juror was explaining how he was an exceptional lawyer and they put Andrew on one of their toughest cases. Yes, that made sense, but there was still very little offered in the court room scenes (the best part of the movie) that made me think that Andrew should win this case.

I love “Philadelphia”. Great movie with fantastic performances. Ever since I first saw it about 10 years ago, it’s been a personal favorite.

I watched it today after not having seen it since I saw it on the original release. I cried like a baby…

Denzel deserved an Oscar just as much as Tom Hanks did..

The fact that Tom Hanks’ character is from such a loving, supportive, and nonjudgmental family annoys me. Most gay people I’ve ever known came from very dysfunctional families, usually a father that was abusive or weak or both. And a mother that was usually domineering.

And how many gay people have you ever known there little fella? I’m gay, aside from extended relatives who like to think they have a place to judge, my parents, brother, aunts/uncles, and all my cousins have never had an issue with it. I’ve been out for 11 years now since I was 13. And while there are definitely cases of some kids coming from broken homes, that can go for anyone, gay or straight. It never ceases to amaze me how hard people try to show how ignorant they are, rather than just getting an education.

Not for one minute did I believe Tom Hanks was a gay man.

I watched Tom Hanks dying of AIDS.

I believed it, but I kind of see where you are coming from. It’s not that he wasn’t “acting gay enough”, it’s that the aspect of his performance regarding his love for Antonio Banderas’ character looked to be lacking compared to Banderas’ performance regarding his love for Tom Hank’s character. I can see where that might make someone feel that Hanks wasn’t gay. That said, the difference can easily be explained by anything from their difference in personality to the effects that the disease was having on both of them.

Don’t get me wrong, I like this film a lot, but I think all the hulabuloo about Hanks’ acting in this film is overdone. He did a very good job, but not a great one. Very good.

No, I’m not homophobic (I thought it was one of the best movies of the year), and no I don’t dislike Hanks (I thought he deserved the Oscar for FG, and probably also should have gotten it for SPR). I thought, for example, that the Opera scene was pretentious and just not as powerful as it should have been, and as it’s touted to be. That said, there are plenty of other scenes that are much more subtle, and more powerful, but aren’t given as much recognition.

I’m not sure if this makes a lot of sense. I just watched the movie again, and was reminded of how good it was and how much I appreciated it–but also of what I didn’t like about it.

Something I will say, that doesn’t get said a lot, is that it has some great writing in it. Cinematography, acting, and direction are always praised in this movie, but I think the writing gets overlooked.

“Philadelphia” was a film that needed to be portrayed, even if it was not reality of a gay society. The straight world, when AIDS became a pandemic in the early 80’s, were quite cruel and obnoxious. If you weren’t old enough to have experienced the world back then, being gay or lesbian was not something that was expressed openly (many were still in the closet) and the straight community was perfectly happy with the status quo. As a matter of fact, having very close friends that were gay I specifically remember reaction from anti-gay sympathizers: Its God’s punishment on “them” for the abominations against Him (God).

“Philadelphia” served its purpose and allowed main stream America to feel the sorrow that this awful disease afflicted on the people that it had infected. The film gave straight America empathy for the gay community, empathy that was long overdue.

Interesting how the issues of representation of AIDS in media has become the issues we see with representation of the trans* community today. Namely, a white male actor playing a character that is the “socially acceptable” version of a marginalized group.

In a way, Philadelphia was important in that it opened up understanding for many people who wouldn’t have even considered empathizing with such marginalization, but details could’ve been changed that would have left its teeth somewhat less filed down: why couldn’t Andy be Black, or less wealthy, or gotten AIDS in a non-“scandalous” way? To normalize something as scary as AIDS, why do we see normativity in whiteness, in wealth, in monogamy, in straightness (despite being gay, Andy is quite asexual)? They could have subverted as least one of those tropes of normativity, but instead made Andy the quintessential stereotype. Sigh.

It is interesting to see the stigma that came with the disease AIDS in 1993. Now we America, has passed gay rights and AIDS is getting more accepted. In seems as though with time people get more educated and accepting of things that were once perceived in a negative outlook. I think if a movie like Philadelphia was released today, it wouldn’t have held a stigma on it because of how the world perceptions on AIDS has changed in a positive way.

I love this! I have never seen Philadelphia but I will soon be watching. Reading this article reminded me of Rent, which was also a very heartfelt movie for me. AIDS is a topic that I find very interesting because of the reaction that it brings. Seeing these reactions come to life from movies is also very intriguing. Thank you!

Very interesting read! I think there’s something to be said about the fact that many early examples of AIDS-related activism has been widely criticized for “de-gaying” the cause, particularly for the AIDS Memorial Quilt and Philadelphia. The filmmakers intended to address a subject as complex as HIV and AIDS, but decided to soften the blow to mainstream audiences by not unsettling them with so-called non-normative sexuality on screen. That being said, I still see the film as a significant step towards a better understanding of the AIDS epidemic, even if the cinematic representation of gay men was deliberately sacrificed in the process. I suppose one could argue that the screenwriters simply had to pick their battles. Thanks for writing!

“Sappy sentimentality” aside, I think that to really grasp the emotions in Philadelphia, it is imperative that we situate the film in its time and place in history- as we should with any movie.

I like that you mentioned the pre-release hype surrounding the film. To fully grasp just how jarring the concept of AIDS in a mainstream movie was, one has to grasp the stereotypes and fear that surrounded the disease before it’s initial discovery. For a time, many communities (at first, predominantly gays) slowly began watching this unnamed, unidentifiable disease creeping up the East Coast of the US from Key West…the Carolinas…to New York City…with no apparent way of stopping it. This must have been terrifying for so many who were hearing of friends, relatives, and acquaintances being affected closer and closer to their homes. This fear created a sensationalism around the film that effectively aided in its box office performance and critical reception, even years after the discovery of helpful medicines.

Time continues, and opinions wane and interpretations become more critical- more than just gay people were affected with AIDS, why did not movie not touch on an impoverished community, or a drug-using community? Did Andrew Beckett need to be a rich, successful white male for the movie to be properly received? Did the film only help to prolong the misconception of AIDS as a “gay disease?” Only time will tell. Otherwise I loved your thorough analysis of specific scenes- especially the sauna scene. Very powerful. Will be watching this film again soon.

At least the movie reached a broad, mainstream audience, so there was education on the topics of AIDS, tolerance, and homosexuality.

This is a very interesting article and, I praise you for pointing out the flaws of this movie. When it comes to movies based off of real life problems, they have to Hollywood it in order to make it interesting to a casual audience

An enlightening critique of what is, for me, anyway, in spite of its flaws, still a very good movie. Thanks for sharing this sophisticated and historically-grounded analysis. Great work.

It was a movie that sugar coated the issues and gave no real thought to the masses of not so flowery members of the HIV/Aids population. Why? I think because, the not so flowery victims of the disease, particularly those who are at the opposite ends of the spectrum from the Andrews of the world, were not as sympathetic to the populace.

I just had the privilege of discovering this great article. I think TKing has done an excellent job of reflecting on the redeeming qualities of “Philadelphia”, which has indeed faced a lot of harsh criticism. A month following Jonathan Demme’s death in April, I think this piece is actually a great commentary on his pop culture legacy.

I have worked part-time as a men’s sexual health counsellor in Toronto for more than 9 years; I do HIV testing and counselling in this role. I guess you could say that I’m in the front lines of the ongoing battle against HIV transmission rates. And I proudly identify as a gay man.

Without a doubt, I agree that the film is highly flawed and a grave misrepresentation of the gay community. It’s also highly unfortunate that it disregards the relentless efforts of grassroots organizations throughout the era. However, I agree that it still succeeds in having instilled a much needed sense of AIDS awareness in popular culture. TKing is right–this film was not made for me. And I’m okay with that.

When I perform an HIV test on a client, one of my pre-test counselling questions it to ask how much they know about HIV. On more than one occasion, heterosexual male-identifying clients of a certain generation (often receiving their first ever test) inform me that they know about AIDS from “Philadelphia”. Although I spend some time informing them of the advancements in the field and ‘correcting’ their perspective, I believe it is a comment on the film’s lasting legacy that these men can at least trace their consciousness of AIDS back to the film’s release in 1993. Despite how problematic, it was still a long overdue Hollywood representation of AIDS. So I say kudos to Demme for this achievement.

Thanks very much for your kind words, and for contributing your informed perspective to the conversation. I’m glad to hear that, from the point of view of someone who has regular contact with the issue of HIV, I did alright with this article.

old history and old people and old remembernace!

Wow. This is possibly the most detailed, respectful, and thoughtful “one-star review” of anything I’ve encountered lately. I feel for the LGBT/AIDS/HIV community about films like this. I also feel with them, because while I am straight and not affected by AIDS, I have a disability. Like these communities, I have too often seen characters in my group marginalized or used primarily as pedants/inspiration porn. It leaves a horrible taste in your mouth, and is a disservice to all kinds of three-dimensional human beings who are routinely denied their God-given rights to live life as they see fit.

Thanks very much for your kind words. Glad you enjoyed the article. I agree with what you say about these kinds of movies: well-intentioned, but ultimately a real disservice – and, as my “one star review” indicates, not very good movies either.

You’re welcome!

While I appreciate the well written and well thought out article, I personally think it over-intellectualizes the movie, “Philadelphia”. I lived in Philadelphia at the time, and this movie did exactly what it was designed to do – it provided an entry-point for “the average person”, whether they be white, black, straight, gay, whatever – into the conversation around HIV/AIDS and to another degree, homosexuality. I was a gay 13-year-old when this movie came out and I can confidently tell readers that the world of 1993 didn’t allow for this type of discussion in mass media. It just was not really done. Maybe that it’s because I have become disenfranchised with the politics of intellectualization as I have aged, I just have come to believe that sometimes we need to take things at face value and judge them for their merits as is, rather than the constant need to dis-integrate “an idea” as it relates to LQBT issues. In sum: there is an ever-increasing tendency in LGBT issues to intellectualizes everything, especially media, and more often than not the result appears to be more and more isolation of ideas so that the work being critiqued is somehow left lacking. “Philadelphia” is and was an important milestone in film, film regarding HIV/AIDS, LGBT film and so on. It did what it was supposed to do, and for that it should continue to be lauded.