Feminism and Food in Film

In real life and fiction, food brings people together like almost nothing else. Eating is rarely the simple act of eating. In many cultural and religious traditions, eating is called “breaking bread,” which hearkens to one of the simplest and most common foods we possess. People come together over food in celebration and in mourning, out of hunger and boredom, out of need and enjoyment. If an author or filmmaker wants to show a character is isolated or unhappy, they often show him or her eating alone. The presence or absence of food can speak directly to not only a character’s socioeconomic status, but what he or she hungers for inside. Impoverished or abused characters like Oliver Twist, Harry Potter, or Sara Crewe often begin the healing process with nutritious, plentiful, and lovingly prepared food.

In recent decades, food has also been used, particularly in film, as a conduit of feminism and women’s empowerment. Considering the staggering statistics on women struggling with anorexia, bulimia, and similar disorders, this might seem counter-intuitive. Yet as two particular films of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century have shown us, food can and does empower women. It helps them discover new facets of themselves, their cultures, and their families. It gives them niches in new and old communities. In some ways, women who prepare, serve, and eat food for and with others act as healing agents through nutrition and camaraderie. Furthermore, it is not only the physically hungry characters around them who benefit, but also the emotionally hungering ones.

Chocolat

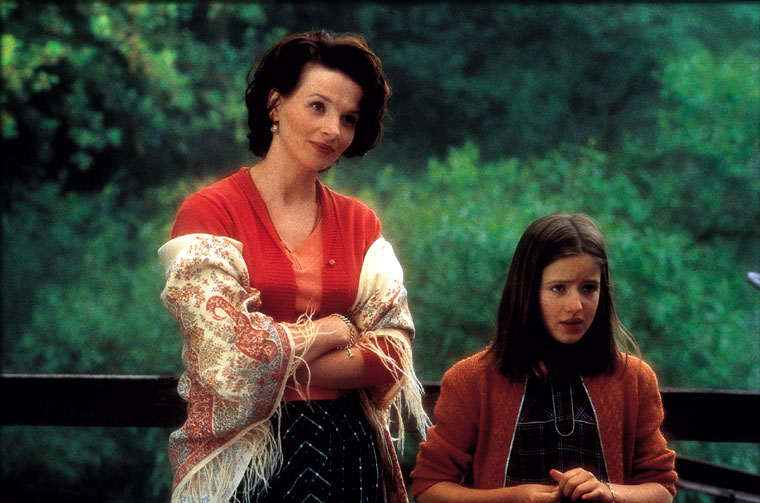

The twenty-first century’s exploration of food and feminism started with a bang in 2000. Lasse Hallstrom’s film Chocolat debuted on December 22 that year. Starring Juliette Binoche, Lena Olin, and Judi Dench and based on a book of the same name, the film focused on one of the most beloved foods of the human palate, chocolate. Protagonist Vianne Rochet is an itinerant French chocolatier whose story begins when she moves to the ultra-conservative village of Lasquenet, circa 1959. She stands out immediately. Where the other villagers wear neutral colors, Vianne blows onto the scene with the north wind at her back, sporting a bright red cape reminiscent of Little Red Riding Hood. Indeed, like Red, she comes with the promise of delivering good food to the villagers (including Judi Dench’s character, spitfire grandma Armande). Along with food though, Vianne somewhat unintentionally delivers freedom and fulfillment to others and herself.

Vianne runs afoul of the Lasquenet residents, particularly Comte de Reynaud (Alfred Molina) almost instantly. He drops by her chocolate shop to be while she and her six-year-old daughter Anouk are settling in, and chastises her for planning to open what is then a pastry shop during the Lenten season. The villagers Reynaud serves as mayor are devout Catholics, so they are meant to focus on penitence and abstinence during this time. Vianne further cements her perceived disrespect of faith and tradition when she tells Reynaud she and Anouk don’t attend church. When she mentions they’ll enjoy singing with the bells, Reynaud takes it as an indication Vianne sees worship as entertainment. Even those who are not so devout, such as Vianne’s landlady Armande, are skeptical of the chocolate shop when it is finished. “What’s the decor?” Armande asks. “Early Mexican brothel?”

Indeed, Vianne’s shop, the Chocolaterie Maya, is unlike anything the villagers have experienced before. As noted, her decor invokes early Aztec culture, possibly a nod to her indigenous heritage on her mother Chitza’s side. She sculpts detailed chocolate statues, some of which look like fertility goddesses, and sells treats including “nipples of Venus,” or voluptuous chocolate kisses topped with tiny nipples of white chocolate ganache. When a new customer enters Chocolaterie Maya, Vianne invites him or her to look into a spinning painting on a wooden wheel and tell what he or she sees there. Vianne uses the answer to guess the person’s favorite chocolate and is usually right. For instance, when young Luc Clairmont responds, “I see teeth…blood, and a skull,” Vianne correctly asserts he loves dark, bitter chocolate. While Luc appreciates and enjoys this game, and others find it interesting, his mother Caroline isn’t impressed. “[The chocolate] will have to wait…Lent,” she scolds, hurrying him out. Though not stated, it’s heavily implied other, more skeptical villagers regard Vianne’s shop as a bastion of light witchcraft, gluttony, false religion, and sexual immorality.

That’s not to say Vianne is a pariah. As the film progresses, she gains plenty of supporters, even if some have to keep said support quiet for fear of upsetting the tranquilitie of their lives and being shunned from church and community. She wins over crusty Armande with a steaming cup of Mayan hot chocolate. We see Armande drinking and relishing it, musing, “Tastes like…I don’t know. Something I had when I was a girl,” and laughing. Josephine Muscat slips into the shop one morning and steals a box of rose cremes. Vianne catches her but doesn’t condemn. Instead, she gently prods, “I have a knack for guessing. These are your favorites, right? On the house.” Josephine drops the box like a bad habit and runs, but Vianne pursues her, and her friendship, later. Josephine eventually opens up to her about her abusive marriage and the fact she has no one to trust in town. “If you don’t pretend you want nothing more in your life than to serve your husband…you’re crazy,” she confides. She adds, “I don’t steal. Not on purpose. People talk; they lie about me.” Vianne consoles her, saying, “[Your husband] doesn’t run the world” and “I don’t think you’re stupid,” which apparently, her husband and a lot of others do think. Thus, through chocolate, Vianne begins the physical and emotional healing of Josephine.

Josephine eventually seeks refuge from abusive husband, Serge, with Vianne, who protects her at the risk of her life when Serge breaks into the shop and nearly strangles her. Thanks to Vianne’s chocolate-laced confidence shot, Josephine brains Serge with a skillet and is able to resist when he shows up in a suit, with flowers, asking her to come home because “we are still married in the eyes of God.” “Then He must be blind,” Josephine says, shutting the door. But Josephine isn’t the only one partaking of Vianne’s delicious goodwill. When Vianne learns Caroline Clairmont is keeping Luc from his grandma Armande because she is a “bad influence,” she engineers a scheme for grandmother and grandson to have quality time together at Chocolaterie Maya while Caroline is at her weekly hair appointment. There, they bond over scandalous poetry (read: with themes of death, darkness, and worms crawling over corpses), sneaking sweets during Lent, and learning to balance a spoon on the nose by the bowl. Vianne’s chocolate is also implied to put the passion back in a lackluster marriage, and the pep in the step of an elderly, beloved dog. She, alone of other merchants, offers food and a friendly face to itinerant riverboat dwellers who come to town. In one case, a chocolate remedy actually appears to soothe a riverboat girl’s stomachache.

The villagers often feel guilty about partaking of Vianne’s chocolate, not just because it’s Lent, but because their brand of Catholicism is heavily legalistic, focusing on sin, vice, and the avoidance thereof on penalty of divine retribution. One montage shows several people at confession, rhapsodizing while repenting. “Chocolate seashells, so small, so plain, so innocent. I thought, one little taste, it can’t do any harm,” Madame Audel says. “It melts, God forgive me, ever so slowly on your tongue and tortures you with pleasure,” another parishioner reveals. Such confessions eventually inspire Pere Henri to subtly condemn Vianne in a sermon, mostly because of Reynaud who tells him what to preach.

But to her credit, Vianne sticks with her shop and her loyal base. She doesn’t say so, but she knows the people of Lasquenet need emotional freedom. They need healing of all sorts. Josephine, for instance, begins to look far healthier physically once she moves in with Vianne and Anouk. For Vianne, chocolate is the best conduit of healing. Director Lasse Hallstrom mentions it in a DVD featurette, agreeing, “Chocolate is medicine, almost, in this movie.” The medicine works, sometimes in tiny teaspoons, like the simple unwrapping of a truffle in church, and sometimes in a big IV like what Armande, Luc, and Josephine experience by coming to the shop on a regular basis. Still, as Vianne discovers, the one most in need of healing from her chocolate, the process of making it, and the camaraderie it brings, is herself.

No matter how well-intended, actions have consequences, as Vianne learns the hard way. Little Anouk comes home one day demanding, “Are you Satan’s helper?” and, “Why can’t you wear black shoes like the other mothers?” Vianne tries to comfort her, but her only offering is, “It’s not easy being different,” which sounds like a platitude. After Reynaud starts a Boycott Immorality campaign against Vianne and the riverboat population, Vianne starts losing customers and thus, friends. Caroline discovers Luc and Armande have been visiting Chocolaterie Maya behind her back and reams Vianne out for it, partially because Armande is a diabetic who hid her condition from Vianne. “She could be blind within a year,” Caroline rants. “Why don’t you just give her rat poison?” As these incidents pile up, Vianne begins losing sight herself–sight of who she is as a chocolatier, a mother, and a woman. She laments to Armande that the whole town is against her. Later, she confesses Anouk, who seems well-adjusted, actually hates their itinerant lifestyle and is unhappy, but Vianne doesn’t know how to handle that. When Armande dies of diabetes and her “sinful, self-indulgent” choices are condemned in the eulogy, Vianne takes on the blame partially because others are silently blaming her. With her spirited, extraverted nature under fire and her connection to the best part of herself–chocolate–dwindling, Vianne must make a crucial choice.

Like most of us do when threatened, Vianne initially turns to what works. She intends to abandon Lasquenet and her few remaining friends before her upcoming chocolate festival. We see her packing up and muttering, “Of course…whatever you like, Maman,” directing the words to an ornate Aztec-inspired wooden urn. This is a callback to Vianne’s own childhood growing up with a mother who abandoned her husband to move with the north wind and “dispense ancient cacao remedies.” Additionally, because the urn contains the ashes of Chitza, Vianne’s mother, its presence signifies Vianne can’t let go. She can’t stop running, and as long as that’s true, she can’t heal from her hurts and traumas. We don’t know specifically what they are, but it can be inferred Vianne, like Anouk, suffered from moving around so much and not having a father. It might also be inferred she grew up around oppressive religion and she and Chitza were actively shunned, except when it came to their talent for creating chocolate treats and remedies. Rather than shield her child from those wounds, Vianne became trapped in a destructive cycle.

It takes Anouk to break that cycle, in a great move on Hallstrom’s part that shows even little girls can be their own women and act as healing agents. Vianne wakes Anouk one morning simply holding out her child-size, identical red cape. Anouk goes into tantrum mode the minute she sees it, signaling, “No, I will not be like you anymore.” Vianne ends up forcing her down their apartment stairs, and in the scuffle, the Mayan urn breaks, scattering Chitza’s ashes. It’s a crystallizing moment for Vianne, who stares silently at the mess and has a much-needed epiphany. Anouk tries to clean up and says, “I’m ready to go now, okay? The next town will be better.” But Vianne sees the turning point before her and takes it, choosing to stay in Lasquenet and hold her festival, despite the fact the town might not support her as a whole and she might be driven out anyway.

In reality, the festival is not only a celebration, but the final mark of wholeness for Vianne and the people around her, especially the women. In a touching pre-festival moment, Vianne nurses Reynaud after finding him passed out and “overdosed” on chocolate in her front window. He had been on a complete fast and perhaps out of ravenous hunger and anger, attempted to destroy Vianne’s shop in a “holy war”-type overture. True to her nature, Vianne offers no condemnation, simply a non-chocolate stomach soother and compassion. Reynaud never comes out and endorses her, and it’s clear they still disagree on faith. But this scene marks Reynaud’s, thus the town’s, turning point for good. Villagers are seen reveling at the festival in an epilogue, including Reynaud and the buttoned-up Caroline, who we’re told eventually go on a date. Luc and Caroline have repaired their relationship too, and though Armande is gone, her spirit lives on in Serge’s cafe, which Josephine took over and renamed Cafe Armande after his death. Pere Henri exhorts his congregation to base their Christianity on “what we embrace, what we create, and who we include,” rather than denial and exclusion.

As for Vianne, she heals and finds her place as a woman because her shop, almost a character in itself, gives her a niche. She has a place to belong, for good. This is cemented when she releases her mother’s ashes to the wind and closes her window, whereas before she’d have answered the call to pack up and leave. She builds on a relationship she began with riverboat captain Roux, and it is implied Anouk will have a father, while Vianne’s business will thrive. It’s probably a more “traditional” ending than Vianne envisioned for herself, but viewers know her ending is not about love, marriage, and the eventual baby carriage. It’s about a woman who is at last accepted for herself, as herself, who finds a community she denied herself too long. Vianne’s true hunger is satiated, not just with every truffle she molds, but every relationship and meaningful moment.

Julie and Julia

Modern American women can find their feminist cores and inner healing in food, too. In 2009, the late Nora Ephron gave us the biopic Julie and Julia, starring Meryl Streep as chef and TV host Julia Child and Amy Adams as writer Julie Powell, living in Manhattan in 2002. When we meet them, Julia is settling into a Paris posting with diplomat husband Paul, and looking for something to do so she won’t become an idle diplomacy wife or a reinstated government worker. Decades later, Julie has moved into an apartment over a pizzeria with husband and fellow writer Eric, plus her cat. She works at a dead-end job as a phone consultant at Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, attempting to clean up the after-effects of 9/11 for fellow citizens but having little success. People call in to yell and call her names like “pencil-pushing capitalist dupe” and “heartless bureaucratic goon.” Julie once dreamed of writing a novel, but only got halfway through, and no one took her up on publishing it.

Julie and Julia might be decades and worldviews apart, but it’s clear both are floundering. Julia lives in an era when most women were defined as satellites to their husbands and nurturers of their children. Julia adores Paul, but doesn’t define herself in terms of him, and is infertile, which would net her pity or disdain perhaps in any decade, but especially the 1960s when the phenomenon wasn’t well understood. For her part, Julie feels stuck, surrounded by corporate ladder-climbing peers who are all far more successful than she is. She doesn’t consider her dreams, such as novel-writing, on a par with what her friends are doing, or likely to bear fruit. Like Julia, she loves her husband but seeks personhood outside him. When she finds out her friend Annabel has a popular blog, it’s too much. “I could write a blog. I have thoughts!” she informs Eric. Julie finds inspiration for said blog in her copy of Mastering the Art of French Cooking. Meanwhile, after trying and being bored out of her mind by hatmaking and bridge, Julia admits her true love is eating and signs up for culinary school. These signify the first moves of both women’s journeys toward feminism and healing through food.

Julie and Julia hit obstacles almost from day one. Julia initially attends a cooking class for female peers and finds they are learning–and struggling with–how to boil an egg. When Julia tells teacher Mme. Brassaurd she was hoping for more advanced lessons, Mme. responds, “But you are not an advanced cook.” Keep in mind, she says this without knowing Julia or having seen her cook; she says this with an air that assumes Julia, and possibly all American women, are ignorant. She tries to dissuade Julia’s culinary ambitions, pointing out the only other available class is “all men and very expensive.” As for Julie, she begins cooking her way through Julia’s mammoth cookbook with the goal of getting through 524 recipes in 365 days while blogging the experience. The Julie/Julia project starts out great, but no one responds for several weeks. Julie gets her first comment and finds it’s her mom, who writes, “Why are you still doing this? I seem to be your only reader.”

Like so many intrepid women before and after them, Julie and Julia press on, mostly because they love food and understand the goodness it facilitates for people around them. Julia gets off to a rough start in cooking class, but tackles dicing a mound of onions and whipping perfectly stiff whipped cream with aplomb, given time. She becomes comfortable and friendly with her male classmates in an era when women weren’t expected to be “just friends” with men or learn and compete alongside them. With her teacher’s help, she embraces the joy within cooking, as opposed to the overly technical and simultaneously overly simple approach of Mme. Brassaurd. Meanwhile, Julie thrills in learning to make quality food in the midst of a fast food culture, and rediscovers community within that. Discovering community can mean interacting with readers over how to kill a live lobster for Lobster Thermidor, or chatting with the Dean & DeLuca clerk about which breads go best with which jams.

Over time, Julie and Julia’s communities expand to include more personal interactions and opportunities for deeper growth. Julia smashes the glass ceiling when she gets a culinary diploma from Le Cordon Bleu, despite the attitude of an ironically anti-feminist Mme. Brassuard. She uses that diploma as the foundation for a cooking class with friends Simone and Louise, who ask her to collaborate on a French cookbook geared toward Americans who do not have cooks. In writing the cookbook and exploring a different creative art, Julia faces fears she doesn’t acknowledge or perhaps did not know she had. In one scene, she and her collaborators meet with Irma Rombauer, author of The Joy of Cooking (Frances Sternhagen). Like Julia’s cookbook, Joy is written for “servantless” American cooks. Rombauer spends their meeting talking about how she didn’t make any money from her first publication and in fact paid the publisher. After Bobbs-Merrill, a legitimate publishing house, picked up Joy, Rombauer says they stole her copyright and tampered with her recipes and index. Julia laughs off the encounter when describing it to Paul, but maintains insecurity about publishing. At one point, Houghton-Mifflin shows interest but ultimately declines because the cookbook is too long. This, coupled with Paul’s announcement that they must leave Julia’s beloved Paris after he is grilled in the McCarthy hearings, shakes Julia’s confidence. She has spent eight years on this cookbook and eight years loving her adopted city, only to lose both. “Eight years of our lives just turned out to be something for me to do,” she laments. What’s admirable though is, like Vianne, Julia is able to push on and maintain her search for a publisher, thus, a unique identity as a woman.

Over time, Julie and Julia’s communities expand to include more personal interactions and opportunities for deeper growth. Julia smashes the glass ceiling when she gets a culinary diploma from Le Cordon Bleu, despite the attitude of an ironically anti-feminist Mme. Brassuard. She uses that diploma as the foundation for a cooking class with friends Simone and Louise, who ask her to collaborate on a French cookbook geared toward Americans who do not have cooks. In writing the cookbook and exploring a different creative art, Julia faces fears she doesn’t acknowledge or perhaps did not know she had. In one scene, she and her collaborators meet with Irma Rombauer, author of The Joy of Cooking (Frances Sternhagen). Like Julia’s cookbook, Joy is written for “servantless” American cooks. Rombauer spends their meeting talking about how she didn’t make any money from her first publication and in fact paid the publisher. After Bobbs-Merrill, a legitimate publishing house, picked up Joy, Rombauer says they stole her copyright and tampered with her recipes and index. Julia laughs off the encounter when describing it to Paul, but maintains insecurity about publishing. At one point, Houghton-Mifflin shows interest but ultimately declines because the cookbook is too long. This, coupled with Paul’s announcement that they must leave Julia’s beloved Paris after he is grilled in the McCarthy hearings, shakes Julia’s confidence. She has spent eight years on this cookbook and eight years loving her adopted city, only to lose both. “Eight years of our lives just turned out to be something for me to do,” she laments. What’s admirable though is, like Vianne, Julia is able to push on and maintain her search for a publisher, thus, a unique identity as a woman.

Meanwhile, Julie nets a large readership for her blog, some of whom send her cooking supplies, although she doesn’t gain attention as a “real” writer, in her words. She, too, faces some fears while learning to cook. Some are kitchen-related; the scene in which she tries steaming a live lobster gets sympathy and laughs. Others are more personal, such as when she celebrates her thirtieth birthday (feasting on the same lobster), and admits thirty is not the terrible milestone she imagined. In a less triumphant but important moment, Julie gets a chance to interview with Judith Jones of the Christian Science Monitor. The elderly Jones can’t make it because of weather, and Julie has what she calls a “meltdown.” Unlike Julia, she voices her fears, irrational though they might be. “What if I don’t make my deadline? I’d have wasted a whole year of my life! I’m getting fat…I have to bone a duck…you can’t even conceive of boning a duck,” she spills to Eric. This touches off a fight, and Eric leaves. In response, Julie stops cooking and barely blogs. In the one post we hear she notes, “yogurt for dinner,” hearkening back to the idea of eating alone as a symbol of sadness. We don’t know if Julie is back to herself until she goes to the grocery store to get cooking ingredients–and runs into Eric on the way home. He reassures her he is “back” too, with a warm, “What’s for dinner?” Julie regains a husband in that moment, and through shopping for food, a renewed sense of who she is becoming through cooking.

Julie’s healing through cooking continues from that point, as does Julia’s, though the latter’s is less obvious or food-centric. Back in the US, Julia continues searching for a cookbook publisher who will treat her work as she wants (possibly still reeling from the Irma Rombauer fiasco). She gets a letter from her newly married sister Dorothy announcing a pregnancy, and collapses crying in Paul’s arms. “I’m so happy,” she blubbers, and we know she is–but she’s also mourning her inability to have children. Paul remains supportive, remarking on exactly what Julia’s prospective publisher can do with itself. Dorothy and Julia’s best friend Avis remain a support system, too, but through this period of transition and mourning, cooking is Julia’s constant. Judging from a montage showing the Childs glorying over food, she becomes quite the culinary marvel. Over time, especially in the montage, we get to see her funny, flirty, unflappable self return inch by inch.

Meanwhile, Julie has learned a few things in the kitchen, too. She triumphs when Amanda Hesser of The New York Times seeks her out for an interview, touching off 65 phone calls from potential publishers and making her blog’s readership explode. Still, she cannot truly “heal” from her fear of a wasted, mediocre life until she comes face to face with Julia. Julie is at first ecstatic to hear the real Julia Child has read her blog, but then devastated because Julia said the blog wasn’t “respectful.” Curled in the fetal position in bed, Julie sobs, “Julia hates me.” She then agonizes over why Julia would say what she did, going into meltdown mode. By this time though, Julie has learned how to pull herself out of meltdowns more effectively. In the ensuing blog post, she confesses, “I am not Julia Child,” and we sense she is finally okay with that. After this, Julie completes the last recipe–boning that duck–with “no fear,” and admits the “perfect” Julia Child in her head, the one she loved, is the one that matters. That Julia, the one with whom Julie had kinship, is the one who taught her to cook. That Julia may not have pulled Julie from the ocean when she was drowning, but she did help her contemporary counterpart find her gift, her passion, and her voice. The movie’s epilogue tells us Julie’s ensuing book has done well, ending with the simple statement, “She is a writer.”

The Final Course

Preparing, serving, and eating food might look unimportant, because it’s something we do every day. In many cases though, food is a conduit for the formation, healing, and final repair of identity, especially for women. Especially in recent films, female characters have turned the antiquated idea that they should “stay in the kitchen” on its head. Yes, they certainly will stay in the kitchen if they want to–because the kitchen is the hub of community and discovery, physical and emotional. Once women like Vianne, Julie, and Julia get through, no one will leave the table hungry, including the heroines themselves. Their stories encourage viewers to find what feeds them in any capacity, feast on it, and offer bounty to others who haven’t found their places at the table yet.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Thanks for the great read. On the strength of this article, I’d recommend the 1987 Danish film ‘Babette’s gæstebud’ (‘Babette’s Feast’). Based on the short story by Karen Blixen (which appeared in her 1958 collection of short stories, titled ‘Anecdotes of Destiny’), it’s the tale of strict religious community in a Danish coastal village that takes in a French refugee from the Franco-Prussian war, as a servant. However, Babette has a secret past and her culinary skills effectively bring new life to the closed community – culminating in a feast for all the senses. Well worth viewing and a cinematic delight. Food really is a language of healing.

Yes, it is! I wasn’t aware of Babette’s Feast as a film, so thanks for the tip. As you might have guessed from the article, I’m also a sucker for stories where downtrodden or abused people are healed at least partially through food (because so many of their backstories involve being denied food as punishment, or not being allowed to eat in the way other people are). I see this pop up a lot in children’s/MG/YA literature, which might give rise to another article.

I really love this. Julie and Julia was one of those movies I watched all the time with my mom when I was younger. Never thought about it through a feminist lens, so I’ll have to rewatch it (just finding an excuse, don’t mind me).

I first saw it with my mom too, when it hit theaters in 2009.

In a world increasingly divided because of our differences, we could all learn something from Vianne’s tolerance and kindness.

Couldn’t we, though? I actually think Pere Henri said it best though, in terms of basing goodness on what we embrace and create, and who we include. That’s one of my favorite scenes in the whole film.

For me one of the greatest food scenes in cinema is Tom and Mrs. Waters having dinner together in the inn at Upton in Tony Richardson’s 1963 film of Fielding’s Tom Jones: a very 1960s cranking up of the erotic implications of Fielding’s witty description.

And then there is the mixture of Eros, Thanatos and food in La Grande Bouffe (M. Ferreri, 1973).

What about the bone-marrow-soup scene from Szindbad by Zoltan Huszarik and the egg breaking scene (what else?) from WR:Mysteries of the organism by Dusan Makjvjyev?

Any number of French films linger, often lovingly, on meals and food. It is not just a stereotype, but has a basis in reality.

These movies made me hungry, it made me want to cook and it made me want to write.

I understand…the Julie and Julia bruschetta scene alone…

Uhm… Julie & Julia. I can’t stand it when people talk while eating, not because I can see the food in their mouths, but because of the sounds they make. By its nature the film is about food and people enjoying cooking and eating, so naturally, everyone is talking and eating simultaneously, but in an unpleasant way; smacking lips, sucking on fingers, munching loudly, mumbling with full mouths, gasping and moaning.

The chewing sounds were enough to make me turn off the movie. I wish they would have muted the annoying stuff during edit.

The split storyline between the julie and julia is very easy to follow and SO RELATABLE.

This movie will make you try some of Julia’s recipes no matter how bad your cooking skills are!!

I loved Julia for her irresistable charm. Julie was just annoying.

I can see why you would think that. Julie does come across as self-absorbed and whiny at times. I don’t think she means to be that way, though. I think she’s just frustrated with her life in general and doesn’t always know how to cope, or how to make better choices in, say, the “friends” she hangs out with. The Cobb salad scene is one that makes me cringe every time.

Love food films. Recently memorable are: The surreal scene in Jamon Jamon where two men club each other (to the death?) with big legs of Spanish ham – I think they fight over Penelope Cruz. And the laced gazpacho in Pedro Almodovar’s Women on The Verge of a Nervous Breakdown.

My fav is the diner scene in Five Easy Pieces.

How about Amélie – ‘cracking crème brûlée with a spoon’.

If there’s crème brûlée of any sort on the menu anywhere I find it very difficult to resist – all because of that film.

Chocolat is one of those movies that I was aware of but hadn’t watched until I read your article on it. A charming film that I am happy I consumed (see what I did there?!).

I do see what you did there, and isn’t it a yummy film?

I really enjoy it, usually watching it every couple of years.

“Preparing, serving, and eating food might look unimportant, because it’s something we do every day.”

Haha I haven’t cooked a meal in like 10 years. It’s a fries and pizza for me.

Noted. I don’t do much cooking either, although I wish I did. Maybe I should’ve said “obtaining and eating food?”

It’s interesting to see so many movies of women trying to find themselves and achieve empowerment through food, considering preparing food has traditionally been looked at as a job for women. It probably has something to do with the fact that, while women have always cooked, only men were expected to prepare food in a commercial context to make actual money.

That’s an extremely good point, and a bit of a double standard. It gets even weirder when you consider how many boys still grow up with the idea that cooking is “for girls,” yet it is so difficult for women to be taken seriously in a professional kitchen.

What’s better than a movie about food? Well, a movie about life that uses food as a coping mechanism! Love them.

How can you not love Meryl Streep.

She is an icon. My other favorite movie of hers is Music of the Heart, which was part of one of my other articles.

I don’t think that Meryl Streep was the best choice to play Julia Child. However, i can’t think of anyone.that could play that role well.

These films are surprisingly a great cure for insomnia!

Why does Julie’s husband have to have such terrible table manners?!?

There’s a Brazilian film I saw at the Latin American Film Festival called “Estomago” which is about how a bum becomes a cook, and using it, works his way up the echelons of the criminal fraternity in prison. It was extremely good. Several great cooking scenes.

Chocolat made me really want to eat chocolate and it made me sleepy.

Simplest of meals concluding Big Night (favourite film ever). Surely the most consoling of all screen scenes.

Big Night – the best food film ever!

I particularly love the nonchalant way Stanley Tucci cooks his eggs.

A tasteful article, thank you.

Thanks for such a thoughtful analysis, really enjoyed it!

This is such a well-written and thorough article! I love your thoughts on women as emotional healers, especially in reference to Chocolat. I never connected that women’s empowerment has such a strong link to food. Thank you for sharing this with us!

Food shows should have equal parts of sex to food.This one didn’t.Very boring.Food porn but no sexuality.

The relation between food and feminism is enlightening. Recently, I started watching the show One Tree Hill, (an oldie but a goodie) and I find that the show also demonstrates feminism through food. Karen is a single mother who was abandoned by the father of her child, yet she has to suffer in his presence, as he resides in the same town as her. She is often shunned by other mothers because of her “bastard child.” However, the wife of her ex-boyfriend (the father of her son) steps up and helps Karen run the cafe, despite the adversity and criticism she receives. The show simply proves that women can be connected in all sorts of ways, and in many films, particularly through food.

Thanks for this article! I like Chocolate very much and it’s great to understand that I’m not alone:))

I think that this is a clever way for feminism to work. Often, as mentioned in your piece, we just assume that a women’s place is in the kitchen, therefore this is what she should be doing. However, there really is the potential for women to command the space and make it into something rewarding for them.

Really great piece!!!

Amazing article, beautiful way of writing

This piece is impressive and heart-warming as well. It has given me a different outlook on the role of female in cooking… or should I say it has precisely put into words how I have always felt about women’s role in the kitchen. A lot more people should read this so they can stop underestimating the importance of their daughters, wives, grandmothers’, or of anybody’s, effort when cooking for them. Definitely will cherish food a lot more from now on.

I absolutely adore food. I always have. This article really brings something to the table (hehe) that emphasizes something greater. I love your take on all of these phenomenal movies. Thank you for thinking the way you do.

delightful article deconstructing two great films.

Another film with deeply culinary metaphors is I Am Love (2009), directed by Luca Guadagnino and starring Tilda Swinton as a Russian expat in Italy. Highly recommended.

A delicacy of the both the literary and the dramatic tradition. Meryl Streep could not have better for the persona behind the enigmatic Julia, as she was for Margaret Thatcher. In any role, Amy is icing on the cake, but in this one it is a true pairing of the senses.

Thanks for the unique insights. I had always put off watching ‘Chocolat’ due to some or the other reason but you have piqued my interest and I will be watching it very soon.

A good essay and I enjoyed both of these movies.

It seems to me that the lesson of Chocolat is that there is a liberation in grounding yourself.

I enjoyed your article! I don’t usually pair feminism with food, but I love the points you made. I agree with the community aspect!