Scary Stories: In Defense of Horror for Children

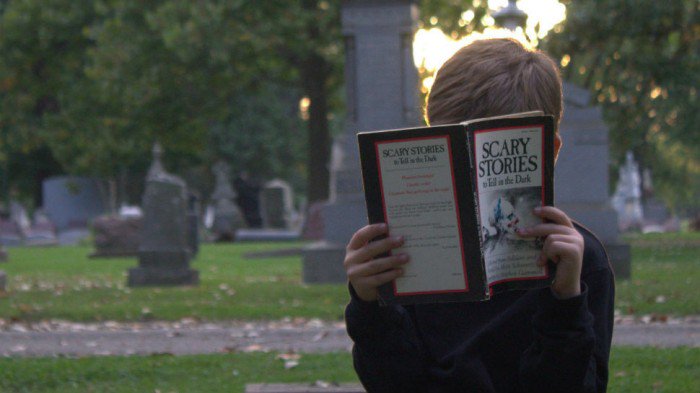

Think back to the scariest book of your childhood. Was it the Goosebumps series, by R. L. Stine? Or maybe the eerie Coraline by Neil Gaiman? Or perhaps it was the viscerally-gruesome Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark by Alvin Schwartz, the spooky story collection with sinister illustrations by Stephen Gammell. If it was the latter, get ready to celebrate: well-renowned horror director Guillermo del Toro is co-writing a live-action take on the books, due to be released in August 2019.

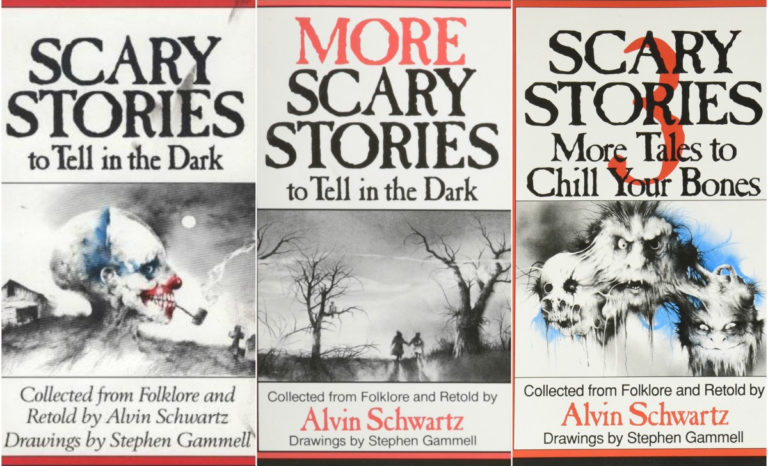

The three-book series, including Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark (1981), More Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark (1984), and Scary Stories 3: More Tales to Chill Your Bones (1991), has left its mark on a generation of kids who grew up surrounded with dark fantasy and horror abounding in their media. But while nineties-kids might look back on these short story collections with affection, many of their parents might groan. Despite the popularity of the books among youngsters, Scary Stories is one of the most banned book series of all time, ranking at number 7 in the American Library Association’s list of top 100 banned books between 2000 to 2009.

With the new film about to be released, and the children who read them all grown up, it begs the question: are books like Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark inappropriate for children? Are they better off banned–and saved for adult consumption?

While parents and teachers may hope to protect their children from frightening content, books like Scary Stories serve a dual purpose. Firstly, they expose children to stories that are obviously separate from the stresses and fears of reality. Kids old enough to read and understand these books on their own are also old enough to know that the ghouls, ghosts, and skeletons of Scary Stories aren’t real. Children should get the opportunity to expand their imagination through challenging themes and concepts, especially horror, as long as it is aimed at their age group. Secondly, children old enough to understand horror as fiction also have the capability to find deeper meaning in these stories, consciously or unconsciously. Through horror, kids can learn that fear is natural and necessary, and that overcoming it brings a sense of power and control that won’t be achieved through overprotective parenting or censorship.

Protecting Children, or Censorship?

The Scary Stories collection features stories that you might hear around a campfire: tales about ghosts, zombies, a wolf girl, and even a particularly nasty spider bite. For those unacquainted with the spooky delight of these books, the collections feature brief stories about a variety of urban legends, folktales, and ghost stories. The stories describe an array of horrors, from gore, to hauntings, to cannibalism and murders. On the gory end, there’s stories like The Big Toe and Harold. In The Big Toe, a young boy finds a severed toe on the ground and takes it home, where he and his family eat it for dinner–only to be haunted by its former owner. In Harold, a sentient scarecrow decides to retaliate against abusive owners and skin them alive. But even the tamer stories, like The Wreck–in which a young boy offers a ride to a girl he meets at a dance, only to find out she had died on the way to the event–are just as disconcerting.

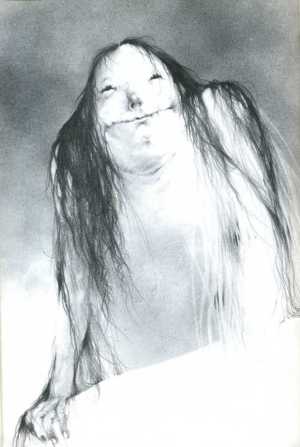

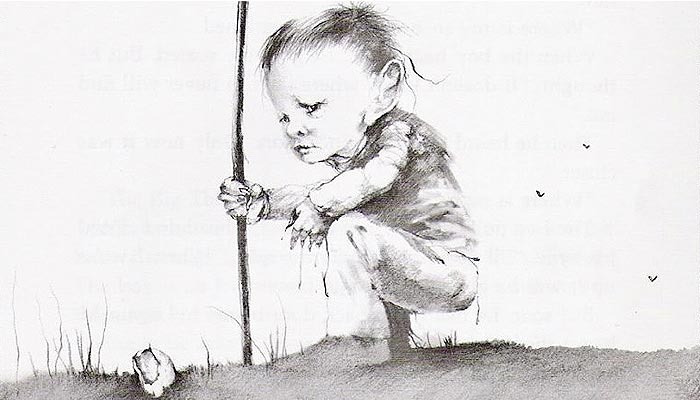

The way these tales are told, using vocabulary on about a fifth grader’s level, along with seriously spooky illustrations, has set Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark apart from many other ghost story anthologies. Unfortunately, it has also attracted the ire of many a critical parent, eager to prevent their kids from reading it.

In 2007, the second book in the series, More Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, was requested to be removed in the Greater Clark County elementary school system in Kentucky for “cannibalism, murder, witchcraft and ghosts”. Despite this, the book was retained in the libraries. More recently, in 2018, one of the books was challenged and removed from the school library at Lake Travis Elementary in Texas for containing “violence or horror.”

These are just a few examples of the reasons why a book might be banned. Racial issues, religious blasphemy or swearing, sexual situations, violence, witchcraft, extreme political viewpoints, encouraging “damaging lifestyles” or even simply “age inappropriate themes” are among the most-cited reasons to challenge a book. In the case of Scary Stories, concerned adults have faced a relatively easy process to initiate a book ban. The first step is a formal challenge, which is essentially a complaint filed with a library or school requesting for the content to be removed. Across the 1990s to late 2000s, the most cited reason for challenging a book was either due to sexually explicit content, offensive language, or simply being “unsuited” for the targeted age group–a claim that can be made relatively easily about almost any story. Statistically, challenges to a book’s appropriateness are usually initiated by an individual, like a parent, or an institution, like a school or school library.

Fortunately for horror-obsessed kids, book banning has largely become a thing of the past. Slate declared that the “there is basically no such thing as a ‘banned book’ in the United States in 2015,” meaning that it used to be much more frequent for books to be banned, and nearly impossible to obtain them after the fact. That changed with the internet era, as a book being banned from a particular school or library just means a reader can find it online. Today, book banning in public libraries is relatively much less frequent. Of the 27 public library complaints filed between 2007 and 2012, only four resulted with a book being removed from circulation.

But even if it’s not common now, it certainly sheds a negative light on a book if it’s associated with the controversy of a challenge or ban. And in cases when schools or libraries do manage to ban a book, some critics posit that it could potentially prevent children from expanding their perspectives, and quash diverse authors and topics. Historically, book bans have disproportionately targeted books written by diverse authors and/or containing diverse characters. Among the Top 100 Banned/Challenged Books from 2000–2009, according to the American Library Association, 52 books included some kind of diversity–that’s more than half–and the majority of these books included diverse content. This diverse content includes addressing issues about race, sexuality and/or disability, or include non-white, LGBTQ and/or disabled characters.

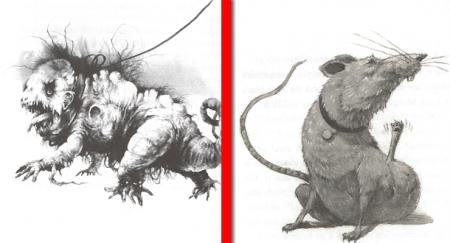

While Scary Stories doesn’t necessarily represent diverse content, its presence as a banned book became a claim to fame, as it was frequently banned due to its themes of body horror and gore, particularly due to its illustrations. Gammell’s illustrations can be noted for their stark use of contrast, abstract forms, and watercolor for an eerie effect of light and shadow. Many of these images left a certain amount of the stories up to the imagination of the reader, offering only a snippet of the plot. Even still, images depict skulls, ghostly forms, a monstrous sewer rat, and plenty of anatomically-odd figures and skulls–and when paired with the stories, create a distinctively shocking, disturbing vibe.

To combat parental outcry, publisher HarperCollins re-released the series in 2011 with new illustrations by Brett Helquist, known for his work on A Series of Unfortunate Events. While the illustrations were less visceral depictions of the stories, the new release was met with criticism and derision. For many fans, many of which were kids who read these books while growing up, the horrific illustrations are quintessential to the experience of the stories themselves. While the stories themselves were not long, the lingering impact of a ghastly figure or warped face contributes to the atmosphere of the stories. After the backlash, HarperCollins re-released the stories in 2017 with the original illustrations in a box set for avid fans, and parents can decide which version they can allow their children to read.

When interviewed about the books and their content, Alan Schwartz claimed that his stories never showed violence, but only implied it. Instead, Schwartz opted for showing gore and suspense, leaving most of the story’s details up to his reader’s imagination. Many of the stories may even sound familiar to parents or children, since they are largely based on folklore, which Schwartz researched using American folklore anthologies and interviews with folklorists. Schwartz wanted to focus on urban legends and word-of-mouth stories rather than just monsters and ghosts. Schwartz particularly avoided real-world problems and horrors, like parental abuse and direct violence, and specifically avoided certain topics, such as self-harm and infanticide, opting for supernatural stories instead.

Learning (and Loving) to Fear

Kids love a good scare. Think about spooky stories told around a campfire, or creepypasta shared on Reddit, or even the infamous Slenderman videos that scared a generation of internet-trolling kids. What attracts children to horror, and should this trend concern parents and teachers?

Regardless of how parents assert their presence to prevent it, every child will face fear. Researchers believe that children are born with certain instinctive fears, while others are cultivated due to social contact. There are innate, or instinctual, fears, and learned fears. While it may feel obvious that everyone should be scared of wild animals, speeding traffic, or creepy spiders, there are actually only two innate fears according to researchers: falling and the fear of loud noises.

Everything else is learned, either through conditioning or experience, and social learning. And while they learn what to fear early on, they don’t develop the complex neural process to interpret these fears until they’re older. Very young kids tend to “freak out” because they’ve fully developed their fight-or-flight response, but their “high road” neural pathways–the ones that allows them to assess a situation before reacting–have not. As a result, young kids will react to a perceived threat, and continue reacting longer than an older child. Take a balloon pop, for example. An adult that hears a loud noise like a balloon pop might be startled, but then recognize it and move on or investigate. A very young child might hear the balloon pop and react by remaining upset for a longer period of time.

As kids get older and their neural pathways develop, they become better able to parse the difference between reality and fiction, real threat and mild fright. Much of their behavior becomes based on what they’ve seen and heard from people around them: parents, teachers, and peers. Parents socialize their children through their words, actions, and reactions, influencing how and when their child might respond to different situations. This is social learning, which combines with innate fears to develop a child’s fight-or-flight response. A parent scared of spooky stories and ghastly illustrations like those in Scary Stories can pass that fright onto their child through contextual and situational learning. Moreover, a child in a class with many peers who are fighting over their school library’s copy of Scary Stories may find the stories to be more exciting than scary.

This research suggests that kids seek out the thrills, and how they react has just as much to do with how their friends, family, and teachers have helped them cope with it.

A Dose of Fright

Research suggests that being scared is actually good for the body and the brain. While scary stimuli incite a physical reaction, repeated scares also help develop the brain by giving us the potential to confront our fears and expand our possibilities. Facing your fears–whether it is riding a scary rollercoaster or walking down a dark hallway–allows us to put our lives in perspective, helping us realize it’s really not that bad at all. Psychologists call this phenomena the development of healthy coping mechanisms, which become tools to help us handle stress in our lives.

Some people may enjoy being scared because it distracts them from other, trivial worries. But other times, feeling scared may also impart a feeling of control in an otherwise uncontrollable world. Assistant Professors of Psychiatry at Wayne State University Arash Javanbakht and Linda Saab posit that much of the “thrill” of being scared is also attributed to the sense of self-confidence that follows from emerging from a threat unharmed:

“When we are able to recognize what is and isn’t a real threat, relabel an experience and enjoy the thrill of that moment, we are ultimately at a place where we feel in control. That perception of control is vital to how we experience and respond to fear. When we overcome the initial fight or flight rush, we are often left feeling satisfied, reassured of our safety and more confident in our ability to confront the things that initially scared us.”

In the human body, being periodically scared actually has health benefits. Activating your fight-or-flight response helps train the heart and the brain. Fear has a specific neural, hormonal, and motor pathway that allows a frightened person to react and respond. The fear response begins in the amygdala in the brain, which determines the emotional significance of any stimuli. If the brain perceives a stimulus as a threat, it will trigger the release of stress hormones or activate physical, motor reaction. Heart rate and blood pressure will rise, pupils will dilate, and blood flow increases. Scary movies, for example, can “train your heart to pump more blood…your heart becomes more efficient at delivering oxygen and draining metabolic waste products away,” says cardiologist Dr. Michael Castine. In many ways, bodies react very similarly to fear stimuli as they would to something that gets us excited–some of the chemicals involved in the fight or flight response are also used in positive emotional states like happiness and excitement.

In Defense of the Scare

Some literature critics may chafe at the notion that a book’s merit is based exclusively on the lessons it can provide. But from a parent’s perspective, children’s literature should at least attempt to expose their kids to good values and ideas that will aid their development. Despite parental concerns, Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark can still be defended. There may still be valuable lessons among the horror–just maybe not in the most obvious or mainstream ways.

Take the story High Beams, for example: a girl is driving home alone late one night when a vehicle driving behind her begins periodically turning their high beams on and off, seemingly without reason. When she arrives home, the vehicle parks behind her, and the driver steps out with a gun. It turns out the driver had seen a killer climb into the back of the girl’s car, and had flashed his high beams every time the killer rose up in the back seat to stab the driving girl. The lesson here? Things are not as they seem, and strangers can be simultaneously dangerous or your saving grace.

Stories like High Beams speak to the fears we have as parents of children: stranger-danger, letting your children grow to have independence, and violence against women and girls. In a strange way, the resolution both confirms and defies these fears, teaching, perhaps, a more nuanced lesson about the world as neither darkness or light. Yes, there are bad people in the world, but there are good ones too.

But what about the stories about random horror, like the quintessential Spider Bite? In this story, a girl gets a spider bite on her face, which grows bigger and bigger until it erupts, birthing dozens of spiders across her face. What lesson is there? What could this story teach impressionable young people, other than that there are endless, terrible possibilities in the future?

Many criticisms of Scary Stories and the horror genre in general for children point to the notion that many horror stories appear as though they really don’t have a moral to be learned. Literature for children tends to focus on applying a “teachable moment” or some kind of lesson to pass on to the child to help support healthy socialization and development. Values are important, and many critics think that horror stories have no place for them. But perhaps it’s something bigger, something more abstract, about the state of the real adult world, that kids will need to learn about eventually. Urban legends and ghosts stories aim to shock and awe, but also remind us that there is a dark, wide world beyond the safety of our childhood. Schultz summarized it succinctly in one interview: “All of these stories, and there are scads of them, are really saying: ‘Watch out. The world’s a dangerous place. You are going out on your own soon. Be careful.’”

Video essayist Zane Whitener posits that horror for kids in the 1990s and early-2000s was never really about the scares themselves, as the images depicted were never about real world threats. Frightening stories about otherworldly monsters and terrible situations can be used to “educate young people about things that normally couldn’t naturally be discussed in a regular story,” Whitener states, citing an episode of Courage the Cowardly Dog that acts as a metaphor for major depression. Spooky books like Goosebumps and cartoons like Scooby-Doo and Courage the Cowardly Dog were part of a zeitgeist of creepily disturbing imagery that kids nevertheless adored, not just because it made them feel frightened, but because it made them feel stronger. According to Whitener, horror has one true lesson, one which every child needs to hear:

“Most horror, I think, especially children’s horror, is about overcoming your adversaries and surviving. It’s about saying in the end that there’s something wrong but you can overcome it. It’s about empowerment.”

Famed horror novelist Stephen King echoes a similar sentiment in Why We Crave Horror Movies. “It can be as simple as to show that we can, that we are not afraid, that we can ride this roller coaster” (525). But it can be more nuanced, about establishing a sense of “normalcy” for ourselves, or a point of comparison for our relatively boring lives, knowing “we are still light-years from true ugliness.”

Based on this theory, it holds that kids old enough to know the difference between fact and fiction, reality and story, are old enough to recognize these stories as spooky, but also not a real threat. The real threats are out there, in the world, not between pages. So letting children read a few scary stories, with the hope that they can stare unflinchingly back at the true horrors of the real world, may not be a bad idea at all. As R. L. Stine said of the Goosebumps books, “the real world is much scarier than these books.”

What do you think? Leave a comment.

A good essay. The section addressing banning books is interesting. Several decades ago I saw a book burning in Florida–which takes banning books to a higher level and is an odd thing to see and wonder what is going through the minds and feelings of those who initiated it.

This is a very well-written article! I especially enjoyed your thoughts on why children should be allowed to read age-appropriate horror. It’s intriguing to see what life lessons can be gleaned from children’s lit, and from the Scary Stories books. I, personally, believe that children’s lit doesn’t always need to teach something. It’s good to have stories that are just fun, too, and scary stories can definitely be fun!

This was a library find when I was around seven or eight or maybe nine years old. Even at that age, I was a spooky little kid (not much has changed, except that I’m taller now) and I absolutely loved anything that could frighten me – and it wasn’t easy to scare me, even back then! I mean, I was watching Freddy Krueger when I was like four years old without even sweating. But Scary Stories book always gave me the chills.

I loved reading R L Stine’s Goosebumps books. I used to polish off one a day at the height of addiction. Then I’d be too scared to go to sleep but they were seriously entertaining.

I used to scare the hell of my three reading them The Hairy Toe at bed time. One day the book mysteriously vanished, spooky or what!!

Amazing article.

Since when was fear a bad thing? Fear is only harmful if it is taken to ridiculous extremes, or if it comes from ignorance vs knowledge. Otherwise it serves the purpose of avoiding harm. Kids also need to eventually learn about the world, warts and all, and stories provide a safe, controlled, monitored manner in which to introduce kids to the world’s more negative aspects.

Furthermore, the ability of a kid to identify with a character in a story (and thus feel any fear in reaction to a scary story) is a very healthy thing. It shows they have both imagination and the ability to empathize. My worry would be about the kid who just sit through scary stories and feel nothing.

What is difficult is finding exciting adventure stories for my eldest grandson.

There is a german story about a boy who gets his thumbs cut off .People took a publisher to court to get it removed from a compendium of children’s stories because of its traumatic content. The ruling by the panel of judges ruled against the plaintives 4 to 1 with a justice Fingers ruling in favour as I remember.

Ahh… Strewulpetter (I’ve not checked Google for correct spelling)

Der Struwwelpeter …

There were about 10 stories in it from memory, all reasonably gruesome endings for the misbehaving child, although when I read it in the mid-1950s, as a child, I loved it as did my daughters in the 1990s.

The ones I remember were a girl who plays with matches burns to death, some children who taunt a dark-skinned child are dunked in an inkwell, a child who refuses to eat his soup dies of malnutrition, the aforementioned finger chopping because of finger sucking and a child always rocking on a chair eventually falling and pulling the entire table on top of him… I can’t recall the others exactly…

To parents, I would recommend starting with Go Away Big Green Monster by Ed Emberley. It gives reassurance to a worried child that they have control over a monster in the book. And it is lovely book to handle.

Other recommends before getting into seriously scary stuff:

Not Now Bernard, Who’s that Banging on the Ceiling (good for fear of night sounds) Look out He’s Behind You (jolly version of LRRH) We’re going on a Bear Hunt and one I think is called Katie’s Ghosts

Traditional tales are sinister and scary. Wolves get Boiled, cross dress in the clothes of their victims, stalk children and get cut open. Little girls break into houses steal and vandalise and still manage to get away.

Grandmothers getting eaten by wolves is not read to children whose grandmothers live in 5th floor apartments safe from those big teeth and big claws!

I once had a parent complain because their child heard an adult say the ‘Three Blind Mice’ nursery rhyme. She complained it was too scary for her child. Some parents feel their children are unable to tolerate any story/rhyme which has anything potentially scary in it. Of course that can make it more difficult for their child to be able to discuss the range of their feelings and to face difficult situations.

Glad those nervous nellies never heard my husband doing his shouty, threatening, weird Grand High Witch voice when reading Roald Dahl to our kids, they’d probably have called child protection.

They loved it. He loved it too. Reading to kids is a chance to open all the doors and let your wannabe actor/inner child run free.

These scary stories books read to me like a screenplay. You don’t come across those that often. These instances are the rare exception in that the film adaptation would reign supreme over the book, just my opinion.

These books scared the crap out of me when I was a kid. I’m still baffled that my mom wouldn’t let me read Harry Potter for several years because she thought Voldemort would be too scary for me, yet I vividly remember having all three of these books. Thanks mom.

Excellently written!

Having read goosebumps through-out middle school, I can certainly vouch for the indirect affect horror themed books can have while growing up. The best part about this kind of literature is that it often lets the reader’s imagination run wild; half the monsters that were conjured were from the depths of our own minds.

Love this insight. Most of the monsters we lost sleep over as a kid, really were creations of our own minds.

I wondered what proportion of parents actually read books to their children at all.

At the moment I’m reading my kids Gogglebook. It’s a book about other people reading a book.

Lovely read. One of our girls was very sensitive and would have nightmares after quite mildly scary stories. We were advised by a psychologist to lay off and let her develop at her own pace. She’s fine with age appropriatte stuff now.

Yes, it’s child dependant.

I have tried to find books that my daughter will find scary and so far I have not found one. If anything she is very fascinated by the macabre and finds the books highly amusing. However, since she has a very safe home life I suspect she has nothing in her life that allows her to relate to fear. A simple example is when she was 4 I read little red riding hood making sure I elaborated on the gory details of the wolf eating the grandmother with screams and legs, body and arms being ripped apart. Was she scared, worried, concerned sad. No not her. She argued with me on the stupid idea that the wolf would be able to dress himself in the grandmothers clothes.

Have you tried The Hobbit? My son loved it – but the spiders in the forest were seriously scary.

I’m reading LOTR to my 7-year old after having read The Hobbit several times to him. It’s a little bit challenging as it’s long and detailed but so far so good – we’ve got to Rivendell at least! But for a boy who couldn’t bear to have skulls on his clothes he is managing the scary factor well.

The books I would avoid with my son were those which show characters utterly failing and being dismissed with no hope of redemption.

One of the worst is ‘Snail’s Legs’ by Damian Harvey and Korky Paul which has a eugenic story line which encourages children to simply keep their heads down and do nothing under a dictator, not something palatable to parents who read ‘The Guardian’.

‘The Adventures of Dish and Spoon’ by Mini Grey is equally disheartening, showing ageing performers simply discarded and compelled to turn to crime.

Do not get me started on ‘The Velveteen Rabbit’ by Margery Williams and William Nicholson. Real children can see through what is happening in the story even if the child in it is fooled. It says that you will be discarded when you have become old and ‘useless’.

These stories, suggesting that only young, energetic people are of any value and that we should do nothing to alter such perceptions, are far more damaging to a child’s healthy growth (let alone interaction with grandparents) than something that might scare them a little.

Did you read the same Velveteen rabbit I did? The rabbit is discarded because the child has scarlet fever. He turns into a real bunny because he is and was loved.

I actually feel kind of sorry that was your interpretation of the book as to me it’s more about teaching children that it’s okay to let things go if you have loved and cared for them. It’s the same message of ‘toys are real’ as shown in Toy Story or a hundred other tales.

The illustrations of Scary Stories To Tell In The Dark were by far the scariest thing about the books, the stories themselves were only okay. I feel sorry for kids who only see the reissued editions with the new art. Those new drawing won’t give a single child nightmares, or a lifetime fear of dogs with people hands, I’d want my money back.

Nobody was joking about how terrifying the illustrations are. It was a fun little kids’ book otherwise! A couple of really good stories but mostly forgettable. The art tho.

I remember reading the books during my late elementary-middle school years and absolutely loving it while being scared out of my mind by some of the stories.

Lovely article. I did not grow up with any of the books mentioned; they were not allowed in my house. (I come from a moderate but observant Christian family, and horror of any kind = Satanic influence, or at the very least, glorification of sin and hate). Now, years later, I still kind of have that stance. That is, I have no desire to read a story or book where say, a scarecrow comes to life and skins abusive owners in graphic detail. For me, it goes against the principle of dwelling on things that are true, right, excellent, and praiseworthy.

But I am *also* an opponent of book banning, or telling kids, “Don’t read this because I/your teacher/our religious leader said so.” If you ban one book, none are safe, and that includes your Bible, Koran, and Torah, by the way. And I definitely see that there can be some value in horror, if it is told well and to the right audience. I would never take a five-year-old to see a Stephen King movie, or let them read Scary Stories… and I’d challenge anybody who did. But let a seven-year-old read Goosebumps? Let a ten-year-old read Scary Stories…? Quite possibly–so I could then say, “What did you think? What did you learn from this? Do you like books like this or want more–and if yes, tell me why, because your old Mom wasn’t that brave when she was a kid.” If nothing else, I’d want my kids to at least have some safe, guided exposure so they can learn (A), The difference between the good and bad in this world (B), What they can handle and when to stop and (C), The real dangers of censorship/the difference between censorship and saying, “Our worldview cautions against this for a good reason.”

Terribly nostalgic about these books.

I’ve read this countless times growing up. The illustrations are amazing and the stories are a lot of fun.

When I was seven, a teacher with a bent for terrifying the most easily frightened child in the class, namely me, told us the story that I later recognized as “Mansize in Marble.” Nothing before or since has ever scared me more. Decades later, if I described it, the hair would still rise on my arms.

In about 1965, P. L. Travers was writer in residence at Radcliffe College. I asked her once if she had read E. Nesbit as a child. She laughed and said, “I know what you’re thinking. If I hadn’t read her, I would probably never have written ‘Mary Poppins.'”

I think the bit where the children visit the future in The Story of the Amulet fundamentally changed me.

Sending this article to my husband, thanks! Coraline and the Graveyard Book, both by Neil Gaiman. My daughter loves them and read them when she was 8. Also loves His Dark Materials trilogy by Philip Pullman and the Rick Riordan novels and they don’t skimp on horror in places or at least violence. The only side effect so far is a love of good fiction and an ability to write with imagination.

I do hope we are not identifying censorship with discerning what is appropriate for children at different stages of development.

On the other hand this is one more reason for telling stories to children as opposed to reading and showing pictures to them. When they listen to a story children usually take as much from it as is right for them. When our eyes are on the children and not on the page we can also calibrate what we say and how we say it and for instance steer our story to calming waters when children are too frightened.

I used to work in a nursery and I’d have to read The Hairy Toe by David Postgate every day. And I’d make those kids jump every time and they’d ask for it again and again. I’m not suggesting we read James Herbert to 6 year old, but kids will get more from an emotional response to a book, and develop a love of reading, than having to sit through more dull stories about feck all which don’t engage them.

I’ve owned a collection of E Nesbit’s sinister tales for years, and would recommend them highly!

It’s been awhile since I read the books (like 20+ years) but if I remember correctly most of the stories were based on urban legends, like “The Hook”, so the filmmakers will need to be careful or their adaptation might become a de facto remake/reboot of the two Urban Legends films—that would be truly frightening indeed.

So much nostalgia, thank you! These were definitely my gateway into horror books growing up. Of course as an adult, the scares aren’t there, but as a child, these were so creepy!

At about age 10, I was thoroughly spooked by “The Enchanted Castle”.

As an adult the stories are not scary. Some are creepy but nothing to really make you jump. As a kid I remember the book mostly for the pictures/artwork.

The first book I remember was ‘Little Black Sambo’ (yes I know, I know). My brother, a generous soul read it to me day after day until he went on strike. I had no option but to learn to read. Sambo’s impending demise and the delicious thought of a tiger being used for chips scared me for years . My early primary school children’s favorite book was ‘Molly Whuppie’. Thirty years later they can still recite it word for word. Even now I feel guilty about it but both children/adults say they adored it because of the violence which ended in the demise of the ogre and because Molly and her sisters lived happily ever after. I and my children were early readers devouring everything we could get our hands on, my brother still loathes Sambo.

Loved this article and the nostalgia it brought back! Funny enough, as a child I adored all these child-horrors such as Scary Stories, Goosebumps, Scooby-doo, and Courage but I don’t stomach horror too well as an adult (“IT” and “Haunting of Hill House” were phenomenal but gave me nightmares for weeks). Curious to see if there’s a correlation between how horror is catered to children and its extremity for an adult audience.

I loved frightening tales as a child, and loathed the sort of soppy rubbish exemplified by the works of A.A. Milne and Enid Blyton. Surprise to say, Beatrix Potter was good at conveying fear — read “Mr Tod” if you don’t believe me.

i think all kind of scarry movies not suitable for childs

I had totally forgotten these. That or blocked them from my memory.

I would think that having a story where a child character confronts evil with courage and emerges victorious is extremely empowering for children.

“Scary Stories” and “Goosebumps” both had a massive influence on my love of writing and the horror genre. I absolutely loved how “Scary Stories” had script-like action lines that instructed the reader on how and when to scare whoever was listening to the story. Children and adults love horror media because it’s just a story; it’s not real. The rush we get from being scared, then realizing it’s not real and everything is OK, is intoxicating. Yes, there are many other reasons we enjoy horror, but I think the “illusion of fear” is the most powerful.

I read Hansel & Gretel to my three year old and she was traumatised – she went pale and hid under the bed and I panicked that I’d ruined her. But the next night? She wanted it again…

The scary things I saw as a child, whether on purpose or accidentally, have remained as some of the most vivid memories in my head, from reading ‘When Mum Turned into a Monster’ to accidentally catching about five seconds of Nightmare on Elm street. Strangely, these things still scare me to this day and I refuse to engage with them, but am a horror fanatic with everything else.

As a child, I remember that I would read or watch horror with my sibling and friends. It turned into a collection of kids trying to outscare one another and also while battling the “evil” in the story. I assume this is why today I love the horror genre in any form of media.

Fear is just as important to embrace to young children as sadness is. I really enjoyed your scientific and literature based analysis and I think the same can be said for horror films when we grow older.

Many people, including myself, often embrace the horror genre when we are going through a rough period in our lives, as, just like you say, it’s a way for us to embrace a feeling that we can control, whereas in the real world, we may be dealing with particular emotions that are difficult to understand and we are sometimes left to ourselves to try and control them. Once we leave the movie theatre or the pages of a book, those anxieties we feel from the situations or characters in those fictional worlds definitely do follow us into our own independent realities. Part of the fear we experience stays within those stories, because we can look away or remind ourselves that it isn’t real, but the best kinds of horror are the ones that mirror a certain aspect of the real world.

These books began to define the type of literature I sought out; I learned to embrace fear and see the intricacies of emotions these fears brought about. From the spooky imagery, to the chilling tales themselves, the supernatural became a real part of my reading habits and what I thought reading was. Reading no longer had to be academic with a set of questions at the end. Instead they could shape the mind in a thoroughly different way. This realization is something that all children should have the chance to experience as they wonder around their school libraries. I myself found different definitions of what reading should accomplish by trying new texts. Banning certain books only hinders this process for young minds.

I hadn’t realized that this book series was so controversial. We still own all three of these books, with the original illustrations. My sister and I were introduced to this series by our mother who used to read them to us as she too enjoyed the spooky stories. I think that the author makes good points about how introducing children to horror can be beneficial. It not only exposes them to a different genre but it also allows them to discover that there is darkness in the world, and that they can survive it. I’m glad that these types of books exist and I look back on these stories with affection. I really enjoyed them as a child.

I don’t read a lot of horror and never did as a child, but I remember one book we read as a class in grade 4, and it scared the jeebies out of me. I think it was Wicked! by Morris Gleitzman. I can’t remember why my teacher decided it was a book worthy of filling 40% of our classtime every day, but it was. I remember so many things about that book so vividly. I remember talking with my friends about it once she’d done reading (ew! I can’t believe they kissed each other with a fish in her mouth! And I can’t BELIEVE she swallowed it!) I think that, as the article says, it gives any child a positive outook on life. It also teaches them lessons that they can take into their life- as well as experience. The focal function of all literature- creating experiences.

Growing up, I read these books, along with plenty of others of this genre, all the time. They would terrify me as a child, but I kept reading them for fun. I don’t think that it’s bad for kids to read books of this type because it helps them expand their mind, as mentioned.

I used to love sharing scary stories with my friends. We would either make them up or recite them from books we had previously read (my favourite was Paul Jennings’ Spookiest Stories). I was never really scared by these stories, and I don’t think any of my friends were either. Banning these types of books would do nothing but take something away from an interesting childhood!!

As a horror fan and father of young children there is a fine balance between emerging thrills that match cognitive developmental timelines and things that will result in kids jumping in bed with me and keeping me awake all night! I believe a slight exposure to some scary things can be fun and beneficial for resilience but must be offset by good judgement and the potential for the manifestation of irrational fears

I was reading H.P. Lovecraft in elementary school and loved every minute of it! Horror literature helps us grow up. It gives us concrete examples of the difference between reality and phantasy so we know what is really something to fear and what is imagined. You never outgrow horror – Stephen King proves it!

The Scary Stories books to me, as a kid, were always pretty terrifying to read. That said, I don’t believe books such as those should be censored from children because of how well written and descriptive they were. Nightmarish, but very good books nonetheless!

Interesting insight on the topic. I was not aware that banning scary stories in libraries was even a thing. I grew up loving horror and reading about all these tales and suspense, especially R.L Stine’s books. Growing up with horror stories, really expanded my imagination and was even exciting to hear about. There is always something about fear that gives you a thrill. I really enjoyed reading your points.

This has been an interstesting and enlightening article, thank you Eden. I am one of those people who has been too scared to read scary books – seriously. I blame this partly on my diet of German fairy tales that were fed to me from an early age. But as I get older I realize that fear can be a good thing (as mentioned in your article) and after reading this I wonder if having faced my fears and read more scary stories when I was younger would have helped me become more confident and self assured in my everyday aspirations as an adult. The answer is probably yes.

I can see this in my own children – the nineties kids who grew up with Goosebumps and other such stories. And the youngest who was watching horror films at an early age and loving them, is now a well balanced young woman.

People’s need to ban scary stories is no doubt a reflection of their own fears and their own inability to recognize that facing their fears can be liberating and educational. I believe that rather than try to stop our children from reading or viewing what we consider to be scary or age-inappropriate materials we could read and watch with them, and in doing so ensure that they see these stories for what they are – fiction and perhaps help them to learn any lesson that are within. The bonus would be that we, the fearful parents, could also learn to overcome our own fears and in the bargain learn more about life.

Horror stories were my go-to reading material as a child (next to unicorn stories). ‘The Big Toe’ was one of my favourites. I agree with everything in this post, and I think it’s safe to say that if my parents told me I wasn’t allowed to read scary stories anymore, I would find some way of doing it behind their back. I think more parents need to realise that if they are going to censor their kid, then their kid is also going to censor themselves to the parents. I think it’s better if they do it in the light where they can ask questions and be educated, rather than doing it in the dark where they have to be secretive and make their own minds up about things.

I agree with you that there is more to literature than morals and lessons. There’s something to be said for teaching via narrative rather than strict logic, but when it comes to literature we can’t overlook its imaginative power. I mean we already live in a world that puts great value on strategic thinking and living within bound, familiar structures. On the other hand, imagination, fantasy, grotesque and irony liberate us from systematic thinking and habitual living. I think it’s valuable for children to read stories with no particular aim, moral ending or lesson. Story telling and the ability to create thrills is valuable in of itself. Moreover, some things just simply don’t make sense and some we have no control over. That’s something children have no problem recognizing but something we like to forget as adults.

It’s interesting to consider the use, value and purpose of horror for all ages, let alone children. This was an interesting and insightful analysis.

While the stories are scary, it is good for children to be engaged and exposed to them at appropriate times. While a 4 year old hardly grasping the concept of lego does not need to be exposed to stories of shadow figures clawing people open, not only as you said is fear (to an extent) a good thing, even just speaking in terms of enlightenment it allows the child to explore a new scene of media which they may enjoy, or even have a passion for, allowing for potential opportunities in the future.

I love the heart and direction of this essay. Censorship, in this case, does more harm than good. People need to give kids more credit in their endeavors to discover what they do and do not find interesting. If a kid reads a disturbing book and finds it to be too unpleasant, they will stop reading and not return to it, similar to a child touching a hot pan.

Censorship of scary stories for children and/or adults alike is not a good thing. I remember reading Grimm’s Fairy Tales as a young kid, and even as I got older, many, if not most of which were about witches, ghosts, goblins, and the like. Wasn’t scared in the least.

Beautiful article!

Horror stories help build another layer of imagination, despite there being no moral lessons. Having access to all sorts of genres also helps bring into light children’s personal tastes, likes and dislikes of certain characters while also supporting them to generate opinions of their own. The only reason why I enjoyed reading horror stories was because my parents wouldn’t let me read them, so it motivated me to explore by myself (can’t blame me, I’m a curious child) I borrowed a few from the school library. Absolutely loved them!

Your use of empirical studies is great. I would recommend just a few more direct link and references in that vein, but that’s not to diminish your work. It’s a good argument against barring access to choice media. Kudos!

It is pretty clear that a lot of research and time went into this article. You made many interesting points, and I especially liked how you included the health benefits of a good scare. I for one love scary stories and I did when I was much younger as well. Luckily, there seemed to be no stigma surrounding them at my small elementary school so I had so problem getting my hands on spooky material as a young child. However, I have noticed that for many children nowadays, even ones in my own family, this is not the case. I think there is nothing wrong with parents looking out for their kids and protecting them from content which could negatively impact their mental state (ex. young children watching R rated movies), but I think that there is definitely an issue today with parents taking protection too far. I believe over-sheltering children can be just as detrimental to their growth as not sheltering them enough.

Wonderful article! I’m very defensive of darker media (such as many Don Bluth films) for children, as they were formative for me, and being a child CAN be terrifying. But these works offer some level of empathy, advice or even, with the Scary Stories books, a thrill. Those Stephen Gammell pieces are on another level!

I remember my parents not allowing me to check these books out of the library, so I would hide in the back section and read a story at a time when we would do our bi-weekly library visit! I had read probably every Goosebumps book by that point and was ready for the “next step” of horror. I still think the absolute thrill of reading something both scary and controversial (to my family) is a huge factor of why I love to read so much today.

I think that children will always seek out things that are forbidden, especially if they are dark in nature! I think the goal of parents should be to provide a space in which children can comfortably discuss things that trouble them in literature, and as adults, we can help them to think critically on these emotional matters.

Great post!

Interesting read, I fear for the possible (though unlikely) inspiration of serial killers that could arise from reading these.

This gives off a similar vibe to the fairy tales written by the Grimm Brothers, where the story told to kids by the parent depended on the child’s behavior.

This article raises an interesting question, and I think it is one that some might see as controversial. I think to the notion of book banning in general, and how that has lead to many amazing books not being able to read by kids for a whole number of reasons. I think you did a good job!