Victorian Gender Ideology: Silenced Sexuality and Suffocating Spheres

In her novel Affinity (1999), Sarah Waters questions and rejects dominant Victorian gender ideology by giving a voice to the voiceless Victorian lesbian, Margaret Prior, and by representing the Victorian domestic sphere as a prison that traps and silences female sexuality and desire. Waters creates female characters who defy Victorian notions of femininity by refusing to conform to the desired image of the passionless, silent, delicate, selfless, obedient “ideal” women. In contrast to this Victorian feminine archetype, the women in Affinity are sexually deviant or experienced, homosexual, deceitful (characters such as Selina Dawes and Ruth Vigers/ Peter Quick), as well as clever, well-educated, passionate, and disobedient (such is the main character, Margaret Prior).

In addition to portraying female characters who challenge Victorian stereotypes of femininity, Waters gives a voice to the silenced Victorian homosexual, raises questions about the silencing of female sexuality, and critiques the repressive, suffocating nature of the haunted domestic sphere existing in Victorian England.

Through her characterization of Margaret Prior in Affinity, Waters examines and rejects Victorian notions of femininity, notions that are used to define the quintessential woman as passionless, domestic, selfless, pure, gentle, obedient, and silent. Margaret comes to represent the exact opposite of this Victorian “ideal” woman, for she is well-educated, passionate, complex, disobedient, and homosexual. While discussing with Selina her sister Priscilla’s marriage, Margaret challenges the rigid Victorian stereotypes of femininity: “But people, I said, do not want cleverness—not in women, at least. I said ‘Women are bred to do more of the same—that is their function. It is only ladies like me that throw the system out, make it stagger–’” (Waters 209). Here, in all her complexity, Margaret separates herself from Victorian beliefs about femininity.

In Spiritualism and Women’s Writing: From the Fin de Siede to the Neo-Victorian, Tatiana Kontou discusses the same scene: “When Margaret talks of ‘ladies like me,’ she not only distances herself from the dominant Victorian ideology of femininity but also from normative heterosexual models” (183). Kontou goes on to comment on Waters’s creation of a “problematic, transgressive figure,” a female figure who enjoys writing and learning, rather than holding dinner parties or shopping—a figure whom Waters uses to reject dominant Victorian gender ideology. With her “extensive education” and her refusal to marry and reproduce, Margaret Prior symbolizes an intelligent, passionate, and clever woman trapped in the prison that is the Victorian gender system—a prison just as cruel and punitive as Millbank, where less socially privileged women are confined (183).

Silenced Sexuality

In addition to her passion for writing, traveling (specifically to Italy), and her “job” visiting the Millbank prisoners, Margaret is passionate towards members of the same sex. Margaret is a lesbian and, in the past, she has had an intimate relationship with Helen, a woman who has now succumbed to the hetero-normativity of Victorian society and married Margaret’s brother. Her sexual attractions to Helen and Selina, later in the novel, contribute to Margaret’s defiance of Victorian gender ideals. Margaret is extremely affected by Helen’s rejection—so much so, that she attempts suicide. This suicide attempt finalizes Margaret’s identity as a psychological rebel existing in Victorian society.

Margaret is not only silenced by Victorian hetero-normativity, but by her mother, and is, essentially, drugged into normalcy. She is forced to hide her true identity in order to exist in a society that condemns and scrutinizes women who deviate from Victorian gender norms and heterosexist expectations. Margaret is silenced by Victorian notions of female sexuality and trapped in the world of the suffocating Victorian household—a world where women are inferior beings expected to be passionless, silent, heterosexual, and domestic.

Margaret is not the only female Victorian character silenced by her sexuality in the novel; in fact, Waters further investigates and disproves Victorian ideologies about female sexuality by linking illness with female sexual repression. Waters rejects the Victorian concept of the passionless, dull woman, incapable of experiencing any type of sexual desire, by portraying sick women who are “healed” by having sex. In Victorian England, it was widely believed that women were not sexual beings, and that they had no sexual desires of their own; and if a woman was sexual, it was a sign of illness or deceit in order to profit from men (i.e. what prostitutes did).

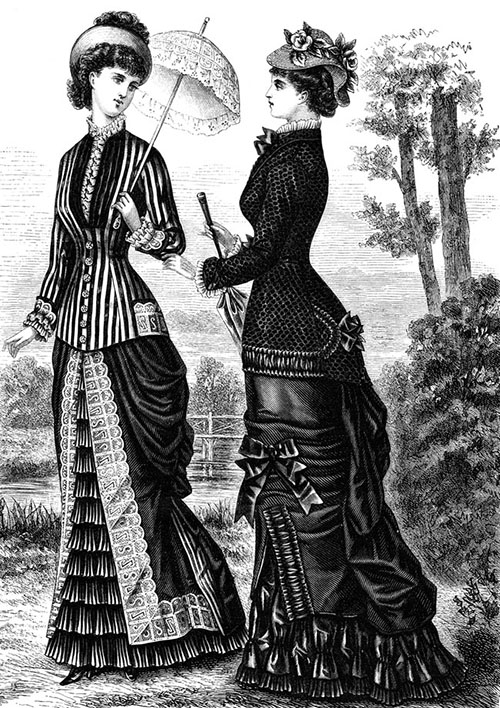

In The Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs […], published in 1865, Dr. William Acton conveys common ideas about female sexuality: “I should say that the majority of women (happily for society) are not very much troubled with sexual feel of any kind. What men are habitually, women are only exceptionally” (133). Further contributing to Victorian definition of the “ideal” passionless woman, Dr. Acton goes on to say, “Many of the best mothers, wives, and managers of households, know little of or are careless about sexual indulgences. Love of home, of children, and of domestic duties are the only passions they feel” (134). It was such expectations and assumptions about how Victorian women and wives should feel and behave that silenced and repressed female sexuality.

Sarah Waters refutes these oppressive gender expectations in Affinity, by creating female characters suffering from the disease of sexual repression. In suggesting that female sexual repression causes illness, Waters proposes sex as the solution, or “cure.” These ill female characters go to Selina with the hope that her spiritualist powers will cure them; however, the cure is not exactly what the women anticipate. The so-called “séances” conducted by the fake spiritualist Selina Dawes and the con artist Ruth Vigers, who is cross-dressed as the spirit Peter Quick, include erotic lesbian sex. It is these lesbian sexual experiences that “cure” the women, which means that the “illness” that these women are suffering from is sexual repression.

Selina and Ruth’s scheming is put to an end, when one of the young women has a bad reaction to their sexual solution and Selina is arrested. During Selima’s trial, none of the “healed” women will testify, because testifying would mean publicly admitting to engaging in sexual activity. The women’s refusal to publicize their sexual experiences with Selina and Peter Quick is emblematic of the novel’s representation of Victorian women as “prisoners of their sex” (Kontou 183). Waters examines and disputes Victorian ideologies about sex and gender by capitalizing on the idea of Victorian women being silenced by sexuality.

The Suffocating Victorian Domestic Sphere

Expanding on the concept of Victorian women silenced by sexuality, Waters takes her analysis a step further in depicting the Victorian domestic sphere as a haunted prison that serves to confine, repress, and flatten the female existence. Kontou discusses the dullness and confinement of the Victorian female future by considering the views of Henry Maudsley (a famous nineteenth-century British psychiatrist) and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (a nineteenth-century British physician, surgeon, and feminist) on “the relationship between women’s health and education” (Spiritualism and Women’s Writing: From the Fin de Siede to the Neo-Victorian, 182).

Maudsley argued the most widely accepted stance at the time, claiming that education and any other areas of interest, or activities not relating to marriage, domestic duties, or reproduction, threatened women’s reproductive health. Considering the dominant Victorian gender ideology, which suggested that women’s sole purpose and function was to marry and reproduce, Maudsley’s argument represented the popular opinion of most Victorians. On the other hand, Anderson who is referred to by Kontou as “a vociferous opponent of Maudsley,” proposed that the docile existence expected of Victorian women was a threat to their health and would result in a lack of mental stability, which she labeled the condition of “dullness” (Kontou 183).

Furthermore, this condition of “dullness” was the reality of the future promised to Victorian women, a future that revolved around getting married, having children, and managing a household. This is the future that Margaret desperately attempts to avoid by refusing to conform to Victorian gender roles and by rejecting the idea that women’s only function is to marry and reproduce. As Margaret reads to her mother, she becomes starkly aware of the shallow, narrow future ahead of her, trapped by her mother’s side in the haunted Victorian household: “In three months’ time I shall be thirty. While mother grows stooped and querulous, how shall I grow? I shall grow dry and pale and paper-thin—like a leaf, pressed tight inside the pages of a dreary black book and then forgotten” (Waters 201).

It is at this moment that Margaret realizes the consequences she must face for going against the Victorian gender system and refusing to conform. Ironically, the so-called “spirits” in Affinity are fake, but the sense of living in a “haunted” domestic sphere is very real. For Margaret, life is haunted by lost possibilities and by the vision of an alternative, freer existence that she can never achieve. Margaret will experience the same dreadful future as the Victorian wife trapped in the domestic prison—not as a wife, but as a daughter caged and confined at her mother’s side in the prison of the Victorian household.

A woman can only take so much pretending and silence, before reaching a breaking point. Margaret’s breaking point occurred when she arrived home after a terrifying day at Millbank, watching Selina get locked up in the dark cell. Characteristic of a woman managing a Victorian household, Margaret’s mother is hosting a “supper-party” that requires Margaret’s silent presence (251). After Margaret attempts to skip the party, her mother puts her in her place: “ ‘Your place is here!’ ‘And it is time you showed that you know it. Now Priscilla is married, you must take up your proper duties in the house. Your place is here, your place is here. You shall be here, beside your mother, to greet our guests when they arrive…’ ” (252).

In the latter instance, the repressive, smothering reality of existence in the Victorian domestic sphere is apparent. Her mother does not demand her presence at the party because she wants to spend time with her daughter; she demands her daughter’s presence because, as Margaret knows: “She could not bear to have our friends believe me weak, or eccentric” (252). If Margaret hadn’t already been uneasy before this conversation with her mother, she most certainly would have felt overwhelmed and distressed afterwards.

Feeling suffocated by the constant need to pretend and to play the part of the silent, passive, polite, heterosexual daughter, Margaret gets intoxicated by taking all the chloral she can, until feeling completely numb. Ironically, the medicine that is supposed to silence and dull her (when taken in the appropriate or recommended dose) provides her with the courage she needs to break her silence:

But the words came from me, I seemed to feel the shape and taste of them as they left my mouth. I might have sat there and been sick upon the table—they could not have silenced me. I said, ‘I have seen the chain-room, and the dark cell. The hobbles fasten a woman’s wrists and ankles to her thighs, and when she is put in them she must be fed from a spoon, like a baby, and if she soils herself, she must remain in her own slops–’ Mother’s voice came again, sharper than before, and Stephen’s joined it. I said, ‘The dark cell has a gate across it, and a door, and then another door, padded with straw. The women are put in it with their arms fastened, and the darkness smothers them. There is a girl in it now, and—do you know, Mr. Dance, the most curious ting?’ I leaned to him, and whispered: ‘It is really I who should have been put there!—not her, not her at all.’ […] ‘But didn’t you know,’ I answered, ‘that they send suicides to gaol?’ (Waters 255)

In this scene, Margaret has finally reached her breaking point. She throws “the system out” and makes it “stagger” by speaking her truth, a truth that is a socially inappropriate topic for discussion, according to Victorian standards of polite social conversation (209). After Margaret is done speaking “out of a fearful kind of clarity,” her mother makes a point of providing her guests with a socially approved reason for Margaret’s suicide attempt and rant. Margaret breaks the silence and puts an end to the dinner party with her “inappropriate” outburst. Here, through the character of Margaret Prior, Waters actively questions and exposes the oppressive nature of Victorian social order, even for those seemingly at the top of the social ladder.

Waters continues with her critique of Victorian gender ideology by analyzing and rejecting Victorian ideals of and expectations about marriage. She refutes the Victorian ideology of marriage by presenting Victorian matrimony as a heterocentric, oppressive system that defines women as inferior to men and functions to force women into a domestic life of “ ‘days filled with make-believe occupations and dreary sham amusements’ ” (Kontou citing Anderson 183). For married Victorian women, this “make-believe” happiness is the reality of what it means to be a woman, “biologically and socially,” in Victorian England (Kontou 183). In Affinity, this vision of superficial activities and feigned happiness is not only characteristic of the life of married women, but is also emblematic of Margaret’s life as a daughter trapped in the Victorian household, forever imprisoned at her mother’s side. Kontou explains the repressive and suffocating nature of the Victorian domestic sphere: “Margaret is to be squashed and inferred between its covers, desires unfulfilled and freedoms never realized” (183). For Margaret, the defiant lesbian Victorian woman, there is no way out, no light at the end of the tunnel, and, like all of the other Victorian women, she is a prisoner of her sex.

Critique of Dominant Victorian Gender Ideologies

Sarah Waters’s Affinity protests against the dominant Victorian ideology of female sexuality, marriage, and femininity with female characters who refuse to conform; and it calls attention to the oppressive, restrictive, suffocating nature of the Victorian domestic prison, which is as punitive as the actual prison at Millbank. The character of Margaret Prior represents the silenced Victorian lesbian who is trapped in a world of sham happiness, enforced silence, and trivial occupations—the world of the Victorian household. Waters calls attention to the ways in which the rigid gender stereotypes and expectations of the heterosexist Victorian domestic sphere silence and repress female sexuality. Affinity counters Victorian notions of marriage, female sexuality, and femininity by giving a voice to the voiceless Victorian lesbian and by using female characters who defy feminine stereotypes by challenging the gender system and social order of Victorian society.

Works Cited

Acton, William. The Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1865. Print.

Kontou, Tatiana. Spiritualism and Women’s Writing: From the Fin de Siede to the Neo-Victorian. Hound mills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. Print.

Waters, Sarah. Affinity. New York, New York: the Penguin Group, 1999. Print.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Affinity is particularly good at evoking the details of time and place.

I never read anything ‘Victorian’, or ‘turn-of-the-century’ anywhere besides this.

Sarah Waters can really tell a story.

Victorian gothic mysteries are the best.

This has inspired me read and or watch this. It sounds very controversial and interesting.

This is definitely fascinating, and I appreciate all the outside research you’ve done for your piece. I really admire authors who use art to take a stand on an issue – to not just entertain, but expose and challenge. However, in my experience, sometimes novels written by a passionate author end up feeling too clunky and agenda-driven. Given that your review dwells more on the oppressive ideology that these characters are attempting to expose than the characters themselves, I’d be concerned about the same thing happening here.

I love Sarah Waters, really.

There’s plenty of Victorian attitudes about the classes and women to get you angry (or me at least!).

Yeah, books like these also make me angry over the treatment of women. Ok, you’re not going to get happy times with a book taking place in a prison, but the Victorian attitudes are horrific. The women are there to be PUNISHED. They’re kept in freezing cells, not allowed to talk to one another, so they forget words when they do get a chance to speak to the lady visitor. And some of the “crimes” they’re locked up for – having an abortion, attempting suicide… Although on the outside world women live in their own prisons, considered feeble minded and to be pitied if a spinster like Margaret, or to be patronised by the men if (to be) married – such as her younger sister Priscella, with her fiance.

Margaret’s obviously been suffering with depression and the fact that she is unable to be herself (homosexuality obviously doesn’t “exist” in these times), so she is forced to take drugs to calm her, by her mother and doctor – despite the fact she is 29, she is treated like a child.

This is one of those stories that sticks with you for days after…the love story was sooo tragic yet beautiful.

I’m so glad I didn’t live back then!

This may be my favorite novel ever.

I was honestly rooting for a happy ending for the main character of Margaret.

Mee too. I guess i think the whole thing was a tad bit far-fetched, and i’m not much of a fan of a story that is so completely unfriendly to its main character.

I disagree. I have to admit the first half didn’t pull me in as much as the second half. The ending was terrific!

The story is quite good and exciting. This article is very well written and interesting. Having said all that, the feminization of nearly everything in modern society is nauseating, to say the least. Moreover, their idealistic and fantasmic stories about the Victorian Period are sheer nonsense and extremely exaggerated. Most people didn’t live in the suffocating silence described by the feminists that write these stories. Human History has so much more to be pleased with and to learn from than most left leaning people are capable of grasping. It’s becoming really distasteful.

I LOVED the twist ending. i wasn’t really expecting it.

A wonderfully atmospheric, gothic story.

AFFINITY broke my heart. I went through several tissues and my heart skipped a few beats through some of the twists and turns.

Sensitive, intellectual Margaret…

Fortunately, the Victorian Age ushered forth many strong female characters and role models in novels by the Bronte sisters, George Eliot, Jane Austen, and other women writers. Too, on the Victorian stage, talented and actresses contributed to the critical re-examination of Shakespeare and the revival of his plays.

Such a complex and brilliant article. I know nothing about the source material discussed here but I shall certainly look into it!

I must admit that I am sorry to have spent a lovely sunny afternoon reading this dark and extremely dissatisfying novel. Now it’s up to the combined efforts of Jane Austen (Northanger Abbey) and Terry Pratchett (Feet of Clay) to revive my spirits and whatever remains of my evening!!

Atmospheric, evocative and beautifully written. One of my favorite work.

Powerful piece of historical noir!

Great piece that could be read on a social or psychological level.

I really enjoyed “Affinity”! It provides a graphic pictures of the very dark side of Victorian England in which we get an idea of the Victorian prison system.

Brilliant article !

I was actually just studying female sexuality in the Victorian Age in my British Literature class today.

Interestingly enough, this view has carried on from the Classical times; think of the depiction of females in the Odyssey. Consider characters ranging from Penelope to the Sirens.

Then think about actual Victorian time novels, and how female sexuality is in all of them ! Ranging from Tess of the U’Durbervilles to Dracula.

Your article takes really good points into consideration, and analyses them well.

This is a fascinating piece. It’s certainly piqued my interest in reading Affinity.

This book sounds amazing! I’m a huge fan of Gothic lit, especially if it explores female queerness and gender roles. Great article!

This sounds like an amazing book! I look forward to reading this book. Great article!

It sounds like a book that’s against what makes all civilisation sane and stable. She is was cleverly promoting that which is ill and perverse.