Bioshock and the Illusion of Choice in Gaming

Choice in video games is not a new concept. Many games produced these days offer nonlinear storylines which allow the player to make a moral choice for his or her character during gameplay. Will you restore order or wreak havoc? Will you seek vengeance or promote justice? Will you follow the path of good or the path of evil?

Of course, when it comes to choice in video games, it is not always an A-or-B decision. Games like Fallout 3 offer the player the opportunity to choose many options in conversation that can improve or decimate relationships with non-playable characters (NPCs), and in turn affect gameplay in the moment or in the near future. The Infamous franchise distinguishes between “Good Karma” and “Bad Karma,” allowing players to take the high road or create chaos, leading ultimately to a “good” or “bad” ending. Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic offers choice in conversations and actions that increase or decrease the player’s Light/Dark Side meter.

But the truth of the matter is that choice does not truly exist in video games. Choice is merely an illusion which we as players believe creates a unique gameplay experience for every individual. Though some games do offer quite different experiences for every player based on the choices made, the outcome and ending are never unique. A game may have one, two, or several possible endings, but that is all players will ever encounter regardless of the choices he has made in the game. To understand this argument, it helps to first examine the differences between linear gameplay and nonlinear gameplay. (Note: Spoilers will follow. Read at your own risk!)

Linear Gameplay

Games with a fixed storyline and outcome are considered linear. Some of the most popular franchises of linear gameplay include the Call of Duty series, the Halo series, and the Assassin’s Creed series, to name a few. These games do not offer the player any choice. Instead, the player follows a set path, encountering the same battles, cutscenes, and ending as every other player in the world. These experiences are not unique, and sometimes that is a good thing. So why might a player prefer linear gameplay over nonlinear, choice-based gameplay?

Linear gameplay eliminates the stress of forcing the player to make his or her own decision. It also allows the player to focus on the story created by the developers, which in turn allows him to enjoy the ride rather than plot a unique course. Additionally, linear gameplay creates a movie-quality game for players to enjoy, something that has become increasingly popular nowadays. Games like Uncharted and Tomb Raider seamlessly integrate gameplay with cutscenes to immerse the player in a life-like experience.

Some of the most widely acclaimed games are linear. Take The Last of Us, for example. Even prior to its release in 2013, The Last of Us has consistently been winning awards. Everything about this game, from the moment the player picks up the controller to the final confrontation in the hospital, is part of a set path, yet players consider this game to be one of the greatest in the modern gaming industry, specifically for its story and characters. If ever the argument arose that nonlinear gameplay is preferred over linear, The Last of Us could instantly shut down that discussion on its own.

Nonlinear, Choice-Based Gameplay

While some players love linear gameplay for its lack of choice, others love nonlinear gameplay for the opportunity to retain control and to create their own experiences.

Back in 2003, Core Design attempted to deviate from the linear gameplay it had always created in its Tomb Raider franchise by introducing choice-based gameplay in Tomb Raider: The Angel of Darkness. Over ten years ago, choice-based gameplay was less common than it is now, so the very concept was revolutionary at the time. Choice in Angel of Darkness did, in fact, have lasting repercussions. For example, if the player ordered Lara to mouth off to the French mob boss, Louis Bouchard, he shot her point-blank, and the game restarted from the last save point.

Although Angel of Darkness received mostly negative criticism and was released unfinished due to internal conflicts between publisher and producer, it was a step in a new direction in the gaming industry. It created a different kind of immersive experience for players that they were not accustomed to in the Tomb Raider franchise. While Angel of Darkness was not the first game to introduce choice-based gameplay, it was among the few that had begun to explore a new paradigm.

But these choices—though they did have an effect on the gameplay—were merely illusions. The introduction of choice in gaming was incredibly alluring when it first became popular because it created a unique experience that made players feel like they actually had some control. However, these choices are limited to a number of options. Games are coded to react to certain choices, so that if the player chooses X, the remaining “not-X” options are then removed from the gaming experience. In essence, choice-based gaming is a technological puzzle which eliminates opposite choices when choice X is made.

If every nonlinear game thus only has a limited number of true choices, what does that say about choice-based gaming? If all choices are different but the outcome is always the same, how does that truly create a unique experience for the player? Some might argue that choice-based gaming is a joke, and they might be right. Two particular games put this into perspective, changing the way players view nonlinear gameplay.

And Then Came Bioshock

Released in 2007, Bioshock received critical acclaim for its creative story, its horrific setting, and its mind-blowing plot twist. Bioshock calls into question all that we think about choice-based gaming, and even life itself beyond that. The player is given few specific choices to make throughout the game, but it is exactly this that proves the point of Bioshock: we are never in control.

The only true choice the player makes in the game is whether or not to save the Little Sisters. The player controls Jack, a man trapped in the underwater city of Rapture, a city in complete shambles crawling with murderous lunatics called splicers. During his journey to escape, he encounters young girls with glowing eyes and massive syringe guns, extracting a substance called ADAM from corpses they find in the city. To survive, Jack needs ADAM, which he can only get by saving or harvesting the Little Sisters after defeating their behemoth guardian, the Big Daddy. This presents the player with the moral choice of the game. If Jack harvests a Little Sister, he receives significantly more ADAM than if he saves her, and this reward is instantaneous.

The choice here is a weighty one. Jack needs ADAM, but at what cost will he earn it? Indeed, the player’s decision does affect the outcome of the game, but there are only two possible endings even so. The ending the player receives is dependent upon how many Little Sisters he saves. That being said, the game does not allow for any moral gray area. The player will only receive the “good ending” if he harvests no more than one Little Sister. Any more than that and he receives the “bad ending.” The game immediately eliminates the good ending by the difference of one Little Sister, thus proving that the ending will never be unique.

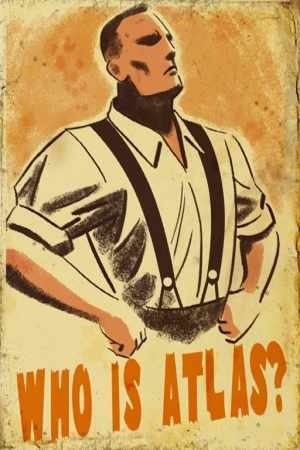

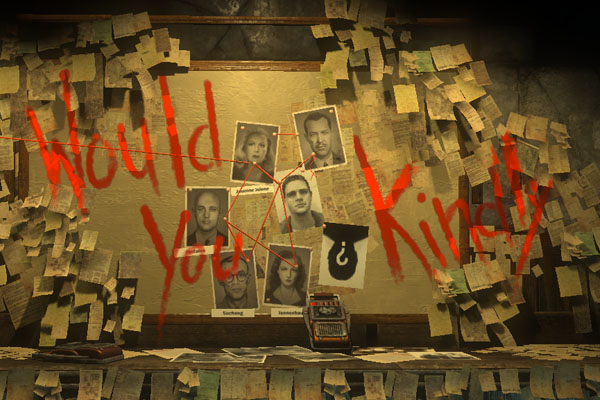

But Bioshock is so much more than that. Saving or harvesting the Little Sisters is the only way the game employs choice—and that is exactly the point. The player eventually learns that Jack did not end up in Rapture by mistake, and that the plane crash that brought him there was no accident. Instead, Jack is the result of a science experiment arranged by someone named Frank Fontaine, who seeks to overthrow the founder of Rapture, Andrew Ryan. Posing as a man named Atlas, Fontaine assists and guides Jack through Rapture with the promise of escape, but Fontaine is really leading him straight to Ryan, utilizing the trigger command, “Would you kindly?” to force Jack to do his bidding. Brainwashed to respond to this command, Jack is forced to follow any given order if this phrase precedes it.

From as far back as Jack can remember, he has unknowingly been a slave to Fontaine, a pawn in the war against Ryan. For every command preceded by “Would you kindly?”, Jack can do nothing except obey. He is physically limited in his ability to act. When ordered to pick up the wrench, lower his weapon, or open a door, Jack cannot proceed until he follows the command. Every choice he has made thus far—even ones as small as picking up the radio when Atlas pages—has not been a legitimate choice at all. Jack simply obeyed, unable to do anything else.

Jack and the player do not learn about the trigger command, his role in Rapture, and Fontaine’s true identity until just prior to the encounter with Andrew Ryan. After being guided through Rapture by Atlas, Jack finds Ryan playing golf in his office, and Ryan seems to be expecting him. “In the end, what separates a man from a slave?” Ryan asks. “A man chooses—a slave obeys. Was a man sent to kill, or a slave?” Ryan, knowing exactly who and what Jack is, hands him the golf club and orders Jack to kill him using the trigger command. Between blows, Ryan continues to scream his mantra: “A man chooses—a slave obeys!” Jack ultimately kills him, putting an end to Ryan’s legacy and essentially handing the keys of the city over to Fontaine.

Andrew Ryan is nothing but a complex character. Unlike his illegitimate son, Jack, Ryan is able to make choices. In fact, he is a self-made man in his entirety who does not take no for an answer: “It was not impossible to build Rapture at the bottom of the sea. It was impossible to build it anywhere else.”

Being who he is, Ryan naturally detests a man who cannot think for himself. His order for Jack to kill him is his final attempt to free Jack from Fontaine’s control, but Jack could not escape. The chain tattoos on his wrists symbolize his enslaved existence. Jack lives his life as a slave from the very first moment we see him until Doctor Tenenbaum removes his programming, thus nullifying the effect of the “WYK” trigger. In fact, the opening scene of the plane crash—the first time we see Jack—is the first of many instances of manipulation. Aboard the plane, Jack reads a note given to him with a gift that requests he kindly not open until 63° 2’N and 29° 55’W, an action which in turn brings down the plane to Rapture’s exact location. Every single moment of his life has been arranged, premeditated, and manipulated to fit someone else’s agenda.

Through Jack, Bioshock makes a bold statement about choice-based gaming. The game satirizes the very idea of it, proving to us that we are never in control of our character, his actions, or his choices. Andrew Ryan, on the other hand, is arguably the most rebellious character in the game, and therefore the most interesting. His order for Jack to kill him is an attempt to override Jack’s programming, to encourage Jack to choose to kill him—not to do it because he is ordered to.

Ryan is a man with larger-than-life dreams and ideals who lives according to the notion of independence and man’s ability to forge his own future by his choosing. Ryan created Rapture during World War II to escape the oppressing fears of war and the puppet masters of bureaucracy. He despises the idea of a greater being in control of man’s fate, hence the banner Jack finds in the lighthouse prior to his departure for Rapture, which reads, “No gods or kings. Only man.” Instead, Ryan believes that man should live in absolute freedom, exactly as he desires. He expresses his philosophy for life in Rapture in a pre-recorded speech delivered to new arrivals:

Is a man not entitled to the sweat of his brow?

“No,” says the man in Washington, “it belongs to the poor.”

“No,” says the man in the Vatican, “it belongs to God.”

“No,” says the man in Moscow, “it belongs to everyone.”

I rejected those answers. Instead, I chose something different. I chose the impossible. I chose Rapture. A city where the artist would not fear the censor, where the scientist would not be bound by petty morality, where the great would not be constrained by the small. And with the sweat of your brow, Rapture can become your city as well.

Andrew Ryan is an incredible idealist who sees free enterprise and capitalism as pure on their basest level. He believes that man can attain anything with enough effort, and that we must all maximize our abilities and opportunities to become great. He is a severe social Darwinist who believes that people, creatures, and civilizations rise and fall because of their own strength or lack thereof. Ryan is a man who believes any means of getting ahead is acceptable even if it is criminal or immoral. His attempt to break the mold and defy the preconceived idea that we are under the control of a higher power is what makes him the most unique character in Bioshock.

Whether or not Ryan succeeds at breaking this mold is a matter of opinion. His laissez-faire approach to managing Rapture is what leads the city to its ruin, as Ryan does not believe anything should interfere with man’s efforts to get ahead, even if it harms another person. But in a dog-eat-dog world, is anyone truly free? Rapture’s collapse does not necessarily mean that Ryan failed, especially since he takes his personal philosophy to the grave with him: a man chooses—a slave obeys. Ryan would rather die a free man than live as a doting slave.

Bioshock presented choice-based gaming in a different light than players had ever seen before. Although Bioshock 2 followed in 2010, fans of the series consider Bioshock: Infinite to be the true sequel to Bioshock. Infinite took the idea behind choice-based gaming a step further—a huge step, in fact.

Bioshock: Infinite and the Multiverse Theory

When Bioshock: Infinite was first announced, fans went crazy. It was not just the prospect of a new game in the series that blew them away, but the game itself and how drastically different it was from its predecessor. Rapture is no longer present, and Jack, Ryan, and Fontaine seem to be nothing more than memories. Infinite instead takes place in a city in the clouds called Columbia. The player now controls Booker Dewitt, a man ordered to find a young woman named Elizabeth in Columbia. He arrives in the beautiful, steampunk-style city and finds it to be picturesque and perfect—too perfect, actually. Racism, religious zeal, and secrets upon secrets hide just under the surface of Columbia’s facade.

Initially, fans pondered whether or not Infinite had anything to do with its predecessor. At first look, the two games are completely unrelated. Everything in Infinite contrasts with Bioshock: Rapture is underwater and Columbia is above the clouds; Rapture is dark and Columbia is light; Rapture is more of a horror setting whereas Columbia, even in its darker moments, is more adventure- and drama-based. But players of the first game can easily pick up on subtle nuances and references to Bioshock. When Jack first arrives in Rapture, a splicer asks, “Is it someone new?” The priest who baptizes Booker asks the same question. Big Daddies are no longer present, but Elizabeth’s mechanical guardian, Songbird, functions identically. From the small similarities to the bigger ones, players of Bioshock will catch the clues if they pay close attention. Of course, by the ending, the player has figured out how Bioshock and Infinite—and Rapture and Columbia—are related: the universe in which Rapture exists is just another reality which Elizabeth can interact with.

But the unique thing that Infinite does is question choice on a much larger scale than its predecessor—that is, the series goes from questioning choice in gaming to questioning choice in reality. Infinite tackled the multiverse theory, a concept which argues that for every choice we make, at least one opposite choice creates a new universe elsewhere, operating in a parallel existence that we will never encounter (Elizabeth, of course, can encounter these because of her ability to open tears, aka portals). Thus, every choice we don’t make is still being made for us somewhere and someplace else. The frightening truth behind this is that we are never in control.

In Infinite, these alternate realities are represented by the lighthouses. Elizabeth tells Booker that the lighthouse is one of the constants in every reality within the Bioshock universe: “There’s always a man. There’s always a lighthouse. There’s always a city.” On the other hand, the variables are the events, relationships, and objects that the characters react to, thus influencing the choices they make.

Booker is quite unlike Jack in many ways. He is able to make small choices that influence gameplay at the moment, yet still have no effect on the story’s outcome. Choosing to rob a store clerk will create trouble for Booker and Elizabeth in the moment, but it has no lasting effect. Choosing the bird pendant over the cage pendant or vise-versa does not alter gameplay. But what separates Booker from Jack runs much deeper than his ability to make minimal choices. For example, Booker speaks, and he speaks often. Jack speaks only once in Bioshock, just prior to the plane crash. One could argue that this was simply a developmental oversight, but that is far too simple of an explanation. Booker speaks to Elizabeth, to other NPCs, and even aloud to himself. Unlike Jack, he is physically capable of acting on his own free will. That being said, Jack’s few words in the opening scene of Bioshock could be nothing more than a thought he expresses which we can hear. Does Jack even speak at all?

Also unlike Jack, Booker has true, legitimate memories of his past. He recalls his infant daughter, Anna, who was taken away from him as a form of payment for his debt. These memories propel him forward in his quest to find and protect Elizabeth. Jack, on the other hand, has only fabricated memories implanted by Fontaine. Without any true memories of his own, he is nothing more than a robot, completely different from Booker who is a unique individual with a past.

Despite all this, Booker is similar to Jack in one specific way: he, too, is being controlled by a higher power, and here, that power is the multiverse. Booker is required to bring back the girl (Elizabeth) to wipe away his debt. To be free, he must complete this task. Ultimately, the person pulling these strings is Zachary Comstock, the antagonist of the game and an alternate version of Booker. The universe controls Booker through Comstock, taking him dangerously close to that slave-like existence Jack has known his whole life. It is not until Booker smothers Comstock at the cradle of his life that Booker and Elizabeth are free from Comstock’s tyranny. To set things right for Anna (that is, before she could ever become Elizabeth, the daughter of Comstock), Booker must erase Comstock, which thereby erases several other realities and the events of Infinite itself. Like Jack, Booker eventually frees himself from control, but it is at a heavy cost.

Again, the argument that Bioshock and Infinite make is that choice is an illusion and that the ultimate consequences of our actions are beyond our control. Infinite might argue that while we may believe our experiences are unique to us (and while that may be true to an extent), the outcome is always the same. The constants in our lives are birth and death—the variables are the events that shape how we live in between these two events.

Indeed, Bioshock and Infinite satirize the notion of choice, which in turn reveals the terrifying truth that our actions are meaningless and ineffectual. It is no coincidence that Ken Levine, the creative director of the Bioshock series (except for Bioshock 2), drew inspiration from George Orwell’s 1984 and Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged in the making of these games. 1984 suggests that a “Big Brother” is watching our every move, whereas Atlas Shrugged, as stated by Rand herself, is about the “role of the mind in man’s existence” (Mayhew, 219). Choice and how we operate through our existence play a significant part in all four of these masterpieces.

Will a True Choice-Based Game Ever Exist?

The future of choice-based gaming is essentially open for any possibility. There will always be new ways in which producers can develop a choice-based experience, but to say that a game will exist where the outcome is unique to every player is merely speculation. Technological innovations in the future of gaming have much to say about how our experiences with games will change, and since the future is limitless, anything is possible.

But something can obviously be said about games like Bioshock and Bioshock: Infinite that put not only our gaming experience to the test, but also our outlook on life. What makes these two games so original is their courage to challenge our presumptions about choice, to boldly profess that no experience is unique and that we are all puppets to some man or machine in control. Whether we believe this or not, these games make these arguments incredibly well. The Bioshock series is very much ahead of its time.

So will a true choice-based game ever exist? Perhaps, or perhaps not. Until then, producers must find new ways to create innovative experiences for gamers, experiences that are unlike those of the standard game, either linear or nonlinear. Bioshock and Bioshock: Infinite are a step in that direction.

Works Cited

Bioshock. Irrational Games, 2007. Video game.

Bioshock: Infinite. Irrational Games, 2013. Video game.

Mayhew, R. Essay on Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. Lexington Books, 2009. 219. Print.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I think it would’ve been cool if they showed you a Catherine-esque graph of all the choices players made by the end of the game.

The measure of an interesting choice is the moment where you make it, not some hypothetical world shaping outcome. By being given the choice, you still have “agency”. It is only the outcome which you have no control over.

Most of the choices in the Bioshock Infinite are more subjective than most games.

Really great read! The youtube channel Wisecrack actually dropped a Bioshock analysis a while back where they, among other things, discussed this concept. It was really interesting to get a more in-depth study on the topic though.

I especially liked the comparison you made between Andrew Ryan’s antiauthoritarian philosophy and Jack Ryan’s lack of free will. That contrasting relationship adds a whole new dimension to their confrontation with each other that I haven’t thought about before.

Well said enjoyed it very much

I haven’t played the games but now I sure want to! I wonder how complex the choices in Fallout 4 will prove to be?

The choices you make in Fallout 4 depend on your allegiance to different factions: the Minutemen, the Railroad, the Brotherhood of Steel, etc. Your allegiance to any given faction will be tested towards the end of the main story-line, to violent extremes in some cases. Unlike Bioshock Infinite, wherein the result is ultimately the same regardless of your decisions throughout the game, your actions in Fallout 4 will have much more significant consequences.

Games like Dream Fall: Chapters and Life is Strange, provide you with choices. The great thing about Dream Fall is that some of the choices are so entwined that you don’t even realize you’re making a different choice than you could have. But other times, a screen pops up and gives you one of two choices. There are a ton of variables though, so you will only have the same gameplay as x number of players, truly.

The Life is Strange ending is a choice between two different outcomes so the choice is moot there, in the grand scheme.

Truly we live in a sorrowful time when the extinction of interactivity is heralded as good game design.

All choices are reward based, choices without consequences only work because you believe there will be consequences. After the curtain is pulled back and you realize nothing you did actually mattered you’re just left with this kind of hollow, empty feeling.

BioShock Infinite is a game about choice, not a game of choice, and it does what it does superbly.

The plot of Bioshock Infinite is, to some extent, a satire on choice mechanics in games; none of the choices actually matter.

I honestly found the most interesting choice to be when you are asked to pick out which brooch Elizabeth should take. No real consequence to it at all or any moral trickery but it is comes out of left field and you are given a bit of a “uh what?” moment. The imagery of them was also designed to ascribe a specific “idea” to each one too. It was just a nice little moment.

Nice work, and many thought provoking ideas.

I love all three Bioshock games but one ending made me tear up is the good ending in Bioshock 2 can’t help it I’m a grown man I can shed a few tears

It’s to help you understand, that even though you make choices differently, some things happened, and will happened, no matter your choice.

If that’s what they were trying to do, that sure is a pretty nihilistic world view. It doesn’t matter if I’m a psychotic, racist who goes around stealing and shooting civilians or I’m the most heroic, good and honest gentleman always ready to lend a hand to the poor or downtrodden. I’m always going to receive the same “fate” regardless.

Who knows, maybe that IS how the world really works. But, it’s almost enough to make me want to believe in karma or a God or afterlife or something.

Only so many scenarios can happen in the game.

This went exactly where it should. Lack of choice in games vs. lack of choice in life. And even though in life we can see choices affect us, it’s probably not always to the extent we imagine. If we marry so and so and have kids, is that life really different than marrying a different so and so with different kids? How different is having one job from a different job. Our lives are probably more linear than we’d like to believe. Grow up, get married, have kids, work the whole time, retire, waste away.

I recently played both The Last of Us and Bioshock: Infinite and I just loved both of them. I think a huge draw with games like The Last of Us (and so many others) is not so much choice but control. You get to choose what weapons you use, what vigors suit your playing style best, what upgrades to get; it is a really minor thing, yet take that away and you really have no control with a game.

Also, I’m a little surprised you didn’t at least mention Heavy Rain with the abundance of “choice” you get with that game.

Rellly enthralling article though. Loved it.

I completely agree with the fact that choice in gaming is a myth. A video game’s story can only have so many outcomes, and because of this people don’t even need to complete the game multiple times to experience the differences in the endings, they can simply go to youtube and watch someone complete the endings they didn’t experience. The Bioshock franchise fits in perfectly with the argument made here too because even though you can choose certain things, the story is invariably the same in regards to locations and characters. There are only minor story changes that primarily effect the final outcome of the game, and I must admit that when I finished these games, I youtube searched the other outcomes. Shame on me right?

Well-thought piece. You do bring up some interesting questions, and made me rethink the idea of choice in games.

Perhaps we need to look at this more like an evolution. There have been games that offer players choice–albeit essentially live or die choice–but the depth has certainly gotten better.

Sandbox games give players freedom, but yes, the missions stay linear. For now, I think the choice is HOW we play the games, not necessarily how the narrative plays out. One exception, though limited, may be Heavy Rain.

Thanks for this paper. Enjoyed it.

No Russian is a great example when it can be done well, but most of the time choices serve to mislead the player into believing they have agency in the world when they really don’t. Any meaningful choice is always going to have “loot” whether it be related to gameplay or story. There is always a reward, and making that reward purely imaginary only serves to make that choice completely flippant and uninteresting.

The necklace choice in Bio Inf seems to be a very deliberate commentary on the nature of the game.

A reminder that I need to play Bioshock!

The ability to make difficult choices is a hallmark in these games.

Where would games like Until Dawn and Undertale lie in your theory? The games themselves have many choices and characters. If those characters die, later interactions with other characters are still available and playable, but the game adjusts for that character’s absence. Are these games “multiverse games”? Does it matter? Would these games be “a step in that direction”? I’d like to know your thoughts on this.

I like the way they handle it. In real life, when you choose to do something, you don’t always know what the outcome will be, or if it will even matter at all. Most things are out of our control no what we choose to do, and I really like that finally being represented in games.

Bioshock was a game where everything came together, it all complimented each other. Infinite was terrible.

My understanding of the Bioshock Infinite is that the so-called “choices” are a joke put in just to add a bullet-point to the features on the back of the the box cover.

The moral choice Bioshock might have been crap, but at least your actions affected something.

The choice-gameplay of Infinite, when you can make some choices in games but they have no overall effect on the story, reminds me of Telltales’ ‘The Walking Dead’ game. In the game, choices are made often, but the story remains the same, with slight variants depending on the player’s choices.

I’ve always thought of the choices in Infinite to be a wry joke from the developers that alludes to the overall theme of destiny and fate disclosed at the conclusion.

But I wonder if we’re actually expecting too much from games in general: do we actually have choices in, say, baseball or checkers? Yes, we make strategic decisions but, even when we’re jumping around with our skyhook, we’re still tied to our rails.

Even when we think about the act of problem-solving: while there are several decisions that have to be made, we tend to take only those that we believe will lead to the optimal result.

What I’m not saying is that we don’t have choices in the real world but it does make one more thoughtful of how our decisions are delimited by numerous factors. Why do we make the choices we make? Is it because of our experience? Our upbringing? Our needs and wants?

This is such an amazing essay! One of the reasons I have trouble focusing enough to play video games is that I more often play Dungeons and Dragons, a game in which choice is also inherent and (with the DM’s help) also infinite. You can play the same adventure module again and again, but by making different choices you can radically change the outcome.

I haven’t played Bioshock but I’ve watched other people play, and this essay does a great job of explaining why they matter so much to the genre of video games. Being aware of the limitations of a form can provoke incredible work and responses in players, as you’ve shown!

So this means the consequences of your choices are entirely pointless?

Not pointless, they serve the game’s themes. They don’t change the game, they change our understanding of it.

I think BioShock Infinite presents a compelling case for telling a story about choice and consequences within a linear video game structure. But the majority of choices don’t have that much impact on the story.

The BioShock story is highly intriguing to me. I’ve played a few video games, but it is highly limited to what I’ve been able to play. I’ve not heard of BioShock, but I am highly interested in playing it to see what it is all about. I would agree that “choiced-based” games are not as “choice based” as we think. Obviously, plots are planned out with each decision made. But even so, I personally play for the stories and learn about the characters.

Other than this, I enjoyed this article. I learned a lot from reading it.

The choices in BI doesn’t make a difference because the story shows having a choice is just an illusion, at the end of the game you can go to 2 lighthouses but both of them end up at the same place. It shows you can’t controll what’s going to happen.

This was a great read.

I agree that there is an illusion of choice when it comes to gaming. I adore TellTale games, but the whole charade of your choices affecting the ultimate outcome is an illusion. Even when you have to choose between 2 characters, the one you save usually ends up dying anyway so the next season can be made without hassle.

That being said, I don’t exactly hate the illusion of choice, it makes me think about my own morals on the spot.

Great article, love it to death.

When asking the question, “Will there ever be a free choice video game?” is a really tough concept for a programmer. Most games are created in a ways to do a few things: create in-depth game-play, tell a story, and possibly use some creative mechanic that brings in your audience. I am having a hard time thinking of a game that could be “finite” in its story. Like others on here, I have to agree with the story having to have some sort of plot. That being said, I don’t ever think there will be a complete “choice-fueled” game. There will always be some aspect that has the illusion of choice. There has to be some already made decisions to create a player a world where they apart of some sort of story.

Maybe I could be wrong, but in the long run it will take a while before we see anything lacking that illusion.

I really liked this piece, but I was wondering if your last question “So will a true choice-based game ever exist?” is kind of pointless. You had some good points, but what about the idea that true choice doesn’t exist in real life. For instance I could kill someone, and unless I am very good at evading the law, I will be placed into jail where my choices will be limited. I would not have the ability to simply change my clothing and go out into the day, nor have a normal life. Of course, games aren’t real life. They offer a virtual reality specifically to create an alternative to real life, but if a game where infinite choices were available to a player I wonder if that game would be slightly boring. After all, Skyrim for example does have limited choices but not so limited as others, as we see that people can mod them, or glitch them out, but even in these cases I wonder if the infinite ability for a person to control everything isn’t necessarily what gamers want, though I think a myth exists that they do.

–just food for thought.

Telltale’s The Walking Dead (at least season one, I have not played season two) truly is an excellent example of the illusion of choice in video games. In this game several choices are presented to the player concerning matters as trivial as what food to give to which members of your survival group, and as major as deciding between which member of your group to rescue when you do not have time to rescue both. However, no matter what decisions you make, no matter who lives or who dies, no matter if you play as a saint or a manipulative jerk- the ending is the same. The end result, even if there are options as to how the end events play out, is always the same. Two different players may play through the game making polar opposite choices in how they act and who they save, but both players will get the end result. This is, in my opinion, the perfect illusion of choice.

Great work. This trend towards choice-based gaming does provide for more interesting narratives on the illusion of choice.

Great article. Thanks for the thoughtful read.

Fascinating view point! Great read!

I love open world gaming, it is so fun and interesting to create your world, however it is interesting to think of it through the lens of the game has a fixed set of options that you are required to work within.

Great article! It was really fascinating to read. While I don’t think any games will ever exist that truly feature free choice, might it be possible for a game to come out some day that has so many endings that it might be considered virtually to have free choice? For example, someone could design a game that has a thousand separate endings that are all slightly different combinations of the same cutscenes, and which ones play and in which order is dependent on the choices you make. With enough endings that it would be pretty much impossible for one person to experience all of them through replaying the game, would that be considered close enough? After all, we all experience the same ending in real life (death), and there are really only so many variations that particular ending can have.

Whenever I think of “choice based gaming” the first thing that comes to mind are the TellTale games (Walking Dead, Wolf Among Us, Borderlands, etc.) which is… rather unfortunate to be truly honest. While the game is lauded for its amazing story and decision based story (things I agree with, I love these games) it does, in the end, feel like almost all the choices you made don’t really matter. You always end up in the same place no matter what you choose.

Not that I can blame them. I can’t even begin to imagine a game where you are constantly allowed to make choices on the level of a TellTale game and actually have them all matter. For what the games are, they’re splendid pieces of story telling, but it’s just so difficult to strike a balance between an amazing story and meaningful choices.

Choices in videogames do seem to have a greater effect to gameplay, especially with recent games such as Fallout 4 and the Tales of the Borderlands series. I can’t wait to see how games in the future will evolve in how the player effects the virtual world they are immersed in.

This is extremely well written. With that said, It seems that your origin of choice within games seems to start from the rise of the console, which I think is an oversight Since you use Fallout 3 within your argument, I think it may be helpful to use the original Fallout to explain what I mean. The cRPG’s of the late 90s like Fallout, Fallout 2, and Baldur’s Gate included choice in the same respect that Tomb Raider: The Angel of Darkness had. In fact, those older cRPG’s included far more choice, and story, altogether. I think that if you were to go back and reconsider this argument using PC games made in the 90s, during the dark-ages of CD-ROM cRPGs, where you navigated through an endless amount of pixels and text boxes, your overall argument would be stronger. After all, Fallout 3 was inspired by Fallout, which was inspired by the Wasteland, made in 1988. So to start in 2003 without specifically referencing the specificity of console games seems to me to be a mistake.

As an aspiring developer, I think it’s worth adding in the capabilities and limitations of the game devs. Personally, I’m pretty disgusted when gamers are disappointed with the lack of result in their ‘false’ agency (see: Mass Effect 3 and Life is Strange). I think it’s a problem devs face whenever they want to make a choice-based game — how can I make every single choice impact the ending? The real answer is that you can’t, it’s simply not possible in a medium in which the developer doesn’t actually interact with every individual person playing the game.

In Dungeons & Dragons, however, the DM knows the players, can adjust the world according to their interactions with the world. In order for games to give us this sense of agency, we’d have to transcend the dev – gamer boundary somehow, which is a conundrum of it’s own.

I loved many of the games you mentioned, and I’m glad to see someone else thinking critically about this medium.

Great article! I just loved the writing and the ideas. I remember playing Infinite with the expectation (from former entries) that my choices would impact the game-play. Only once I played the ending, I came to understand the point that you are making.

On a more philosophical note: the whole idea of freedom of choice, even outside videogames, is very complex. If you have the time, I would recommend On the Freedom of Will; a tiny book where Arthur Schopenhauer makes the case that, since every action or thought a person has belongs to a cause, there’s is no free-will, but an infinite chain of causes.

This was absolutely incredible. Never before have I seen such an in-depth and riveting piece on choice in video games. Great job.

Excellent article! I loved the article and your thoughts on Bioshock and choice. The comparisons you mentioned of Colombia and Rapture were things I never thought of. In my opinion, I don’t think you can have a game where the player chooses his or her fate because it would be impossible to gauge all the choices the player could do. This conclusion leads me to believe that the appeal of choice is more attractive than actually having it.

You writing about bioshock in this way makes me want to write a video game so badly! Nice comparative analysis between the two Bioshock Games!

Thoroughly enjoyed reading this as I enjoy thinking about the topic while playing games like the Witcher, and recently, Superhot, a game where at the end of each level it forces you to “hand over the control” to proceed. I think it will never be possible for a game to give players every conceivable option and include every consequence thereafter while still keeping the ability to be called a video game.

One game recently that impressed me with it’s amount of choice was Fallout 4. You can play the game in many different ways and there are many functions of the game that you do not have to interact with unless, you want to, even in relation to the story. *Spoilers for late game Fallout 4 ahead* After entering the institute and finding my character’s son terrified at the sight of this man he did not know, I promptly shot the leader of the institute in the face as he entered the room and exited the building after rummaging around for all the duct-tape I could find. I found out from friends who played the game with a bit more patience than I, that the man I shot was my character’s real son. Some might’ve instantly scrolled through the load menu to see if they still had a save early enough to commence a do-over. But I relished in the freedom Bethesda provided, in letting me choose.

I think there are games out today that give players the opportunity to make choices with consequences. I don’t think they are perfect but they satiate me.

Fantastic piece! I never really thought much about the illusion of choice in game, but this has definitely made me think. The illusion to Orwell and Rand was also something I never connected the dots about.

Nice article, the insights on the games are profound and well-developed! I’ve lately heard of a soon-to-be-released online game that I forgot the name of, but apparently it involves a universe with (literally) billions of planets that the players will be free to explore and name as they venture into it. To me this is the next step with choice in gaming, because even the makers of the game don’t know the full content of it. Everything is therefore not pre-determined.

Quite an interesting read! I had never looked at the Bioshock series through this lens before, but it makes so much sense.

Nicely done, mate! Incredible article.

In my opinion, Infinite satirizes game endings the same way Bioshock (the first one) does to choice. Like you so eloquently said, Bioshock foregrounds the fact that we never truly have any choice in the game– despite our impressions of them. Infinite criticizes the player for expecting the choices made during the game to affect the ending by having only one (as opposed to the original Bioshock’s multiple endings). Infinite shows that choices can be significant without affecting the ending; they intrinsically matter because it characterizes Booker/the player and creates your individual experience. In a sense, the ultimate goal of the game is not to reach the ending, but for the player/Booker to spend time with Elizabeth in a way that is unique to every experience.

In all honesty I haven’t given Bioshock too big of a chance. I’ve played it maybe for 4 hours overall. I do love games which give me the option to choose “my way” – Mass Effect for example is one of my favorites.

All in all, great article, you’ve instigated me to try out Bioshock once more 🙂

Wow this is an incredible article!

The choice I made in Bioshock Infinity which they ask me to chose between cage or bird I never understood what effect does it have in the story..!

This is something a professor of mine and myself have been playing with for quite some time. The illusion of choice is clearly the largest player in the Bioshock series, and as such it is used as both a motivator and a demotivator. I believe that the illusion of choice used in the context of the Bioshock games works perfectly, because it understands that we, as players, want to think that we are making the decisions in the game, and yet at the end of the day, we are at the mercy of the 1’s and 0’s playing behind the screen. I think that to make a truly choice-based game will be impossible, at least with our current technology. To look at something that is even procedurally based, such as No Man’s Sky, as having choice is impossible. The narrative will still be the same for the most part. All the major parts still exist. Even in something like Infamous, no matter if we choose the good or bad side, we will always fight Kessler at the end, learn of our past, and then start Infamous 2 being chased by the Beast down to New Marais.

We all love the thought of being able to choose everything in a game, but right now, the illusionof choice we currently have, whether used to the best of its abilities, or having it turned on its head, is where we currently stand.

Good article, solid research, and a well versed conclusion.

What a fascinating way to look at choice in video games. Indeed Bioshock changed the way we look at choice once in 2007 with its initial release, and then again with Infinite. Even with massive sand-box games like Elder Scrolls it makes me wonder how much choice a player really has. Either way, a destiny is pre-arranged not matter how much “choice” a video game appears to have.

I love the series, but hate that the choice you make doesn’t hold any weight to them.

Reading this got me thinking about text-based adventure games. They supposedly offer a lot of choice, admittedly constrained by a few commands, but those commands can apply to any word the player pairs with them. But really, even something as simple as language prevents real choice in these games. The inability to pair a command with anything more than a basic object. For instance, in real life, you can take an action in a very specific manner with a motivation behind it and in a certain context. The text-based games may let you take that action, but the rest of it is lost because only that verb can be typed into the computer.

Great article it shows how much work it is to get anywhere close to real choice.

I think that if a video game with actual choices were to ever exist, it would have to be such that the user could augment and evolve the game as he goes, much like how the world of the internet has grown.